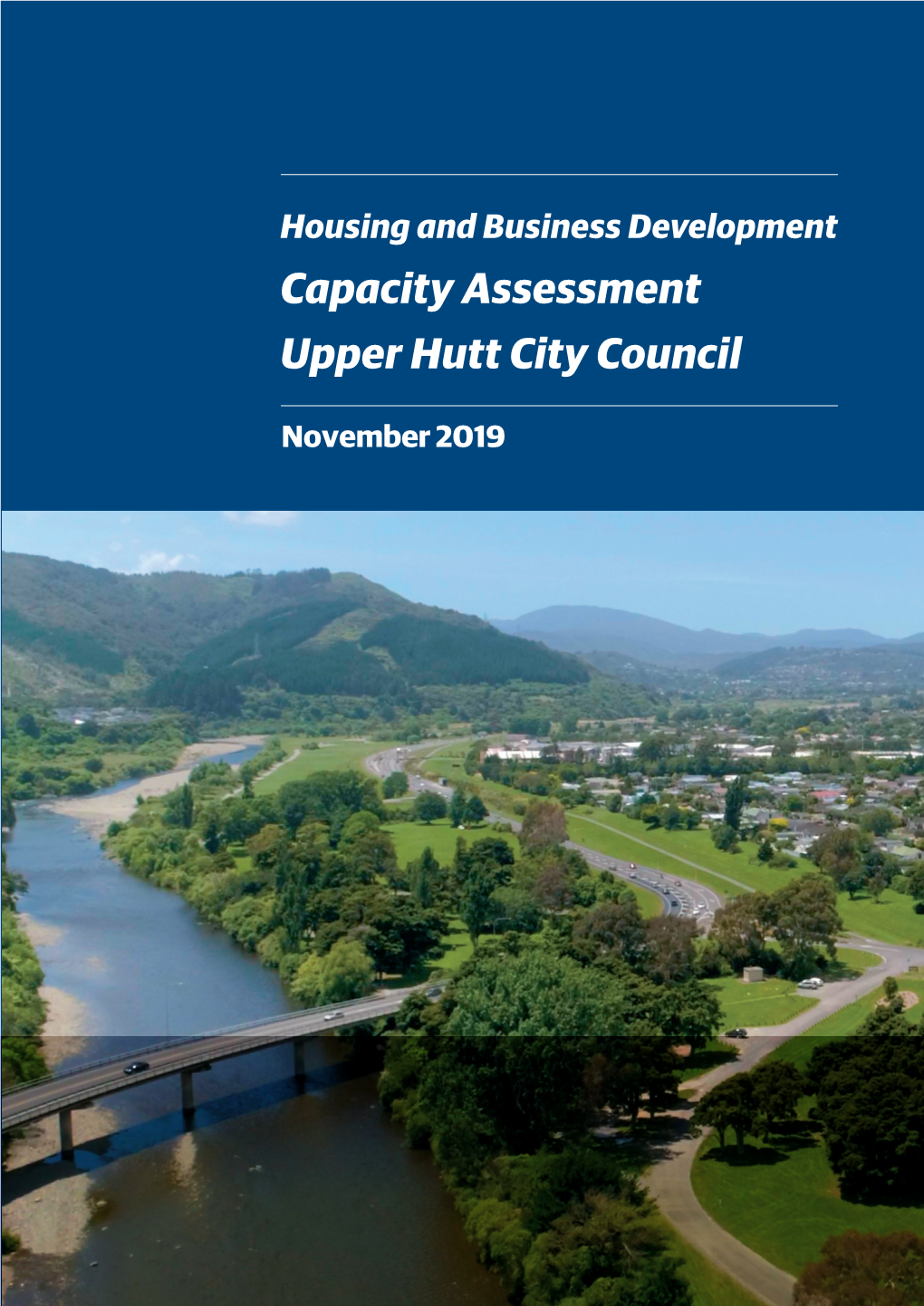

Capacity Assessment Upper Hutt City Council

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pinehaven Community Emergency Hub Guide

REVIEWED JANUARY 2017 Pinehaven Community Emergency Hub Guide This Hub is a place for the community to coordinate your efforts to help each other during and after a disaster. Objectives of the Community Emergency Hub are to: › Provide information so that your community knows how to help each other and stay safe. › Understand what is happening. Wellington Region › Solve problems using what your community has available. Emergency Managment Office › Provide a safe gathering place for members of the Logo Specificationscommunity to support one another. Single colour reproduction WELLINGTON REGION Whenever possible, the logo should be reproduced EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT in full colour. When producing the logo in one colour, OFFICE the Wellington Region Emergency Managment may be in either black or white. WELLINGTON REGION Community Emergency Hub Guide a EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT OFFICE Colour reproduction It is preferred that the logo appear in it PMS colours. When this is not possible, the logo should be printed using the specified process colours. WELLINGTON REGION EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT OFFICE PANTONE PMS 294 PMS Process Yellow WELLINGTON REGION EMERGENCY MANAGEMENT OFFICE PROCESS C100%, M58%, Y0%, K21% C0%, M0%, Y100%, K0% Typeface and minimum size restrictions The typeface for the logo cannot be altered in any way. The minimum size for reproduction of the logo is 40mm wide. It is important that the proportions of 40mm the logo remain at all times. Provision of files All required logo files will be provided by WREMO. Available file formats include .eps, .jpeg and .png About this guide This guide provides information to help you set up and run the Community Emergency Hub. -

Upper Hutt Tennis Club Submission Final Draft Combined

Upper Hutt Tennis Club Submission for the Upper Hutt City Council Draft Annual Plan 2014-2015 Introduction The Upper Hutt Tennis Club (UHTC) supports the Upper Hutt City Council in its plan to establish tennis courts at Maidstone Park under its 2014/2015 draft annual plan. The plan shows commitment to sport in the community and expands an already very active and popular sports hub. The council has invested significantly in the development at Maidstone Park over recent years providing modern first- rate facilities for football and hockey that will serve those sports and the community for many years. As the council looks to invest in tennis, it is essential to consider and understand the specific needs of tennis and how this opportunity provides for the exciting revitalisation of Tennis in Upper Hutt, now and in the future. This submission is about revitalising tennis and realising the potential for the growth of tennis within the Upper Hutt community and the value that tennis will bring to the Maidstone Park sports hub and the city of Upper Hutt. Upper Hutt Tennis Club has a vibrant and long history of tennis in the community. See Appendix 1 We are willing to make a financial contribution of $150,000 towards the development of tennis at Maidstone Park, in order to achieve the goals in our own strategic plan and to benefit the local community. Vision for the Tennis in Upper Hutt The UHTC‟s vision for tennis over the next 20 years is based on the success of other like-minded tennis organisations in New Zealand. -

From Quiet Homes and First Beginnings 1879-1979 Page 1

From Quiet Homes and First Beginnings 1879-1979 Page 1 From Quiet Homes and First Beginnings 1879-1979 "FROM QUIET HOMES AND FIRST BEGINNING"* 1879-1979 A History of the Presbyterian and Methodist Churches in Upper Hutt who, in 1976, joined together to form the Upper Hutt Co-operating Parish. By M. E. EVANS Published by THE UPPER HUTT CO-OPERATING PARISH Benzie Avenue, Upper Hutt, New Zealand 1979 *Title quotation from "Dedicatory Ode" by Hilaire Belloc. Digitized by Alec Utting 2015 Page 2 From Quiet Homes and First Beginnings 1879-1979 CONTENTS Acknowledgements Introduction ... THE PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH, 1879-1976 St David's In the beginning, 1897-1904 .... Church Extension, Mission Charge and Home Mission Station, 1904-23 Fully Sanctioned Charge. James Holmes and Wi Tako—1924-27 The Fruitful Years—1928-38 .... Division of the Parish—1938-53 Second Division—The Movement North —1952-59 .... "In My End is My Beginning"—1960-76 Iona St Andrew's THE METHODIST CHURCH, 1883-1976 Whitemans Valley—1883-1927 .... Part of Hutt Circuit—1927-55 .... Independent Circuit: The Years of Expansion—1955-68 Wesley Centre and the Rev. J. S. Olds .... Circuit Stewards of the Upper Hutt Methodist Church—1927-76 OTHER FACETS OF PARISH LIFE Women's Groups Youth Work .... THE CO-OPERATING PARISH, 1976-79 To the Present And Towards the Future SOURCE OF INFORMATION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS PHOTOS AROUND THE PARISH IN 1979 OUTREACH TO THE FUTURE BROWN OWL CENTRE Page 3 From Quiet Homes and First Beginnings 1879-1979 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is my pleasure to thank Mrs M. E. -

Greater Wellington Regional Council Hutt Valley Public Transport Review

Attachment 1 to Report 14.423 Greater Wellington Regional Council Hutt Valley Public Transport Review Data Analysis Summary Report September 2014 TDG Ref: 12561.003 140915 data analysis summary report v1 Attachment 1 to Report 14.423 Greater Wellington Regional Council Hutt Valley Public Transport Review Data Analysis Summary Report Quality Assurance Statement Prepared by: Catherine Mills Transportation Engineer Reviewed by: Jamie Whittaker Senior Transportation Planner Approved for Issue by: Doug Weir National Specialist – Public Transport Status: Final report Date: 15 September 2014 PO Box 30-721, Lower Hutt 5040 New Zealand P: +64 4 569 8497 www.tdg.co.nz 12561.003 140915 Data Analysis Summary Report v1 Attachment 1 to Report 14.423 Greater Wellington Regional Council, Hutt Valley Public Transport Review Data Analysis Report Page 1 Table of Contents 1. Preamble ....................................................................................................................................... 2 2. Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 3 3. Context .......................................................................................................................................... 4 4. Operational Review ....................................................................................................................... 7 4.1 Overview ............................................................................................................................ -

TRENTHAM UNITED HARRIERS & WALKERS Welcome Pack 2018

TRENTHAM UNITED HARRIERS & WALKERS Welcome Pack 2018 1 CONTACT Email: [email protected] Website: www.trenthamunited.co.nz Facebook: www.facebook.com/trenthamharriers Have a question but not sure who to ask? Email us at the above email address and we will get back to you! 2 2018 Executive Committee President Vice President Philip Secker Richard Samways Mobile: 021 0520202 Email: [email protected] Club Captain Secretary Stephen Mair Lisa Kynaston Mobile: 021 02727325 Mobile: 021 1851757 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Treasurer Administration Manager Vacant Brett Wilby Communications Manager Michael Du Toit Mobile: 022 0725494 Email: [email protected] 3 Short History of the Club The Trentham United Harriers & Walkers Club started in the late 1950s and was then known as the Petone Athletic & Cycling Club. However, because this Club only catered for summer events, there was increasing interest and discussion involving a winter option. The proposal for a winter harrier session was proposed at a Special General Meeting of the Petone Athletic & Cycling Club and in the year 1958 the Petone Harrier Club was formed. And so our Club began. Three people who were part of the initial group promoting the Petone Harrier Club were Allan McKnight, Dave Smith and Jack Powell. Allan McKnight’s mother became the first Patron in 1958. Each Club strives to be different, adopts a monogram or insignia and the Petone Harrier Club was no different. A competition to find a suitable emblem was conducted amongst members and the winning entry, based on the Mercedes-Benz badge, was provided by Bob Mitchell and the new emblazoned uniform appeared in 1962. -

Attachment 1 Wellington Regional Rail Strategic Direction 2020.Pdf

WELLINGTON REGIONAL RAIL STRATEGIC DIRECTION 2020 Where we’ve come from Rail has been a key component of the Wellington Region’s transport network for more than 150 years. The first rail line was built in the 1870s between Wellington and Wairarapa. What is now known as the North Island Main Trunk followed in the 1880s, providing a more direct route to Manawatū and the north. Two branch lines were later added. The region has grown around the rail network, as villages have turned into towns and cities. Much of it was actively built around rail as transit-oriented development. Rail has become an increasingly important way for people to move about, particularly to Wellington’s CBD, and services and infrastructure have been continuously expanded and improved to serve an ever-growing population. The region is a leader in per capita use of public transport. Wellington Region Rail Timeline 1874 1927 1954 1982 2010 2021 First section of railway between Hutt line deviation opened as a branch Hutt line deviation to Manor EM class electric FP ‘Matangi’ class Expected Wellington and Petone between Petone and Waterloo Park, creating Melling line multiple units electric multiple completion 1955 introduced units introduced of Hutt line 1876 1935 Hutt line duplication to Trentham duplication, Hutt line to Upper Hutt Kāpiti line deviation to Tawa, creating 1983 and electrification to Upper Hutt 2011 Trentham to 1880 Johnsonville line Kāpiti line Rimutaka Tunnel and deviation Upper Hutt 1 Wairarapa line to Masterton 1 electrification Kāpiti line 2 1938 replace -

Battle of the Bus Shelter

Be in to win GGreatreat TToyotaoyota a Toyota Yaris GGiveawayiveaway P19-27 Upper Hutt Leader Wednesday, November 2, 2016 SERVING YOUR COMMUNITY SINCE 1939 ‘‘I’ve hit a dead end with the Greater Wellington Regional Council Battle of and Paul Swain, our representative here’’ Dean Chandler-Mills the bus shelter COLIN WILLIAMS Dean Chandler-Mills is taking to the tools. A several year battle to have a bus shelter built at the terminus stop of the 110 service in Gemstone Rd, Birchville, has left the 70-year-old frustrated. A 100-signature petItion was delivered to the regional council in 2013 and plenty of letter writing and submission-making since has produced nothing. ‘‘I’ve hit a dead end with the Greater Wellington Regional Council and Paul Swain, our representative here, ’’ he said. Chandler-Mills said residents were looking at building their own shelter in an effort to highlight the issue. ‘‘There are a lot of people really angry about this. Patronage on the service is increasing and this is not going to go away. ‘‘The next step will be to form a group and build our own shelter. That’ll embarrass the regional council.’’ The Gemstone Rd terminus is next to an open paddock, the width of several sections. ‘‘It services more than 110 households but it is in one of the most exposed commuter areas in the Hutt Valley,’’ Chandler-Mills said. The former Public Service Association organiser recently took his issue to Upper Hutt mayor Wayne Guppy. ‘‘Wayne has expressed an interest in getting some movement on this. -

Upper Hutt College

Changes to some school services Effective from 28 January 2013, there are changes to some school bus services operated by Runcimans. These changes include discontinuing some school services, variations to some services and the introduction of some new services. Please note that any school bus services to and from Riverstone Terraces, or Lower Hutt suburbs to Lower Hutt Schools operated by Valley Flyer are not affected by these changes. Fares and Using Snapper on public bus routes Some of the changes detailed below require the use of public bus routes as an alternative to discontinued school bus services. The Runcimans term passes cannot be used on public bus routes, they can only be used on dedicated school buses operated by Runcimans. Credit can be loaded onto your Snapper card which can be used to transfer between Runcimans school routes and public bus routes at no additional cost, but you need to make sure that you tag on and tag off of each bus otherwise you will pay more than you need to. Transfer options are not available for the train, although monthly passes at significant discounts are available. Planning your journey We have made some suggestions below as to which particular timetabled public bus services and transfers between them may best suit your travel needs. You should however plan your journey at www.metlink.org.nz, in case there are other options more suited to you. Journey Planner information in regards to new and changed services will be available from 7 January 2013. Information on changed, new and discontinued school bus services The following information is presented by school, but in many cases school buses are shared between different schools. -

Heretaungasummaryreport.Pdf

1 Neal Swindells Practical & Principled Independent Educational Consultant Email: [email protected] 1 July 2021 Report to the Ministry of Education on the Community Consultation Regarding Proposed Changes to the Heretaunga College Enrolment Scheme: May - June 2021 Summary Following a meeting with Shelley Govier, Lead Adviser Network, and Jeena Baines, Network Analyst, at the Ministry of Education Wellington Regional Office and meeting with the Principal of Heretaunga College, Fiona Craven, I launched the consultation on the proposed changes to the Enrolment Scheme for Heretaunga College on May 24th, 2021. The consultation took the form of a letter emailed to both the Presiding Chairs and Principals of 16 state and state integrated schools in the Upper Hutt area. These schools included the two state secondary schools; Heretaunga College and Upper Hutt College; the two Intermediate Schools, Maidstone Intermediate and Fergusson Intermediate; and all the state primaries as well as the two Catholic State Integrated primary schools in the area. The letter had links to the proposed changes to the Enrolment Scheme and maps showing the proposed changes. I then offered Heretaunga College, Upper Hutt College, the two Intermediate schools and St Joseph’s School a short communique designed to be sent to parents / whanau and asked them to send these out to their community to try to ensure all Year 8 parents in the district were aware of the proposed changes and the consultation process. I had a number of conversations with the acting Principal at Maidstone Intermediate whose pupils were likely to be the most directly affected group. Both Maidstone Intermediate and Heretaunga College published the proposed changes to their whole community. -

13 Spring Creek

Marlboroughtown Marshlands Rapaura Ravenscliff Spring Creek Tuamarina Waikakaho Wairau Bar Wairau Pa Marlboroughtown (1878- 1923) Spring Creek (1923-) Pre 1878 1873 4th June 1873 Marlborough Provincial Council meeting included: This morning petitions were presented by Mr Dodson in favour of a vote for. Marlboroughtown School; from 15 ratepayers, against the annexation of a portion of the County of Wairau to the Borough of Blenheim another vote of £100 for a Library and Public Room in Havelock was carried. Mr Dodson moved for a vote of £50 for the School in Marlboroughtown, but a vigorous discussion arose upon it regarding Educational finance, in which Mr Seymour announced that Government would not consent to the various items for school buildings, and upon the particular subject being put to the vote it was lost. 11th June 1873 The following petition, signed by fourteen persons, was presented .to the Provincial Council by Mr George Dodson; To his Honor the Superintendent and Provincial Council of Marlborough, in Council assembled We, the undersigned residents of Spring Creek and Marlboroughtown, do humbly beg that your Honorable Council will take into consideration this our humble petition. That we have for some years felt the necessity of establishing a school in our district, and having done so we now find a great difficulty in providing the necessary funds for its maintenance, and we do humbly pray that your Honorable Council will grant such assistance as will enable us to carry on the school successfully, as without your assistance the school must lapse, We have a Teacher engaged at a salary of Fifty (50) Pounds per annum, and since the commencement of the school the attendance has been steadily increasing showing at the present time a daily average of twenty (20) children. -

District Plan Definition of Minimum Yard Requirements

DISTRICT PLAN DEFINITION OF MINIMUM YARD REQUIREMENTS This information sheet explains the District Plan Rules in relation to yard requirements, and how these should be measured to ensure that they comply with the City of Lower Hutt District Plan, or with an approved Resource Consent. Yard requirements should be measured from the property boundary to the closest part of the building, to include any cladding. It is therefore necessary to site the building slab and frame to ensure that cladding does not encroach upon the yard requirement. District Plan Interpretation Reason for yard rule in the City of Lower What this means is that no building, inclusive of Hutt District Plan its cladding, can be closer than 1.0 metre from The reason quoted in the District Plan for the yard the side and rear property boundaries, or 3.0 rule is as follows: metres from the front property boundary. This The yard spaces provide space around dwellings means that no part of a building (except those and accessory buildings to ensure the visual listed in the exceptions above in the definition of amenity values of the residential environment are building, or in the exceptions listed in the yard rule maintained or enhanced, to allow for maintenance above) can be closer. of the exterior of buildings, and provide a break Architectural drawings sometimes show between building frontages. measurements from the slab edge or building The front yard space is to ensure a setback is frame. However, in the case of resource consent provided to enhance the amenity values of the drawings the dimensions need to be shown from streetscape, and to provide a reasonable degree the cladding, if they are not, the yard requirements of privacy for residents. -

Name School Place Oivia Yule Upper Hutt Primary School 1 Grace

Year 4 Girls Name School Place Oivia Yule Upper Hutt Primary School 1 Grace Broome Silverstream School 2 Olivia Grinter Mangaroa School 3 Annabelle Smith-Mays Trentham School 4 Bailey Nightingale Upper Hutt Primary School 5 Kera Birdsall Fraser 6 Dayna Witana Upper Hutt Primary School 7 Emma Bateson Pinehaven School 8 Julia Gray Oxford Crescent School 9 Jessica Perry Silverstream School 10 Gabby Taia Birchville School 11 PAIGER GARWOOD Totara Park School 12 Olivia Withers Upper Hutt Primary School 13 Zoe Pepper Silverstream School 14 Sarah Du Toit Homeschool 15 Sarah Tiatia Saint Joseph's School 16 Violette Billington Pinehaven School 17 Gibeon Pole’o Saint Joseph's School 18 Renee Houghton Plateau School 19 Jada Cant Saint Joseph's School 20 Danielle Bryers Birchville School 21 Michelle Law Upper Hutt Primary School 22 Poppy Millington Silverstream School 23 Christina Werahiko Trentham School 24 Bree Keenan-Dwan Trentham School 25 Lily Gillies Saint Joseph's School 26 Deanna Gotlieb St Brendan’s School 27 Grier Kelly St Brendan’s School 28 Lola Stamenic St Brendan’s School 29 Zoe Watts St Brendan’s School 30 Matangihau Nuku Saint Joseph's School 31 Sophie Noys Silverstream School 32 HUIARAU HOHUA Totara Park School 33 Brianna Martin St Brendan’s School 34 Melaine Holden Silverstream School 35 Bella-Rose Johnson-Walker Saint Joseph's School 36 Ava Ekenasio Saint Joseph's School 37 K’siah Wilds-Toa Temarama Birchville School 38 ANIKA SNAITH Totara Park School 39 Danielle McLennan Trentham School 40 Brooke Binner Silverstream School 41 Mya