Efficacy of Antiretroviral Compounds Against Toxoplasma Gondii in Vitro

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Article PDF/Slides

Kan Lu, PharmD New Antiretrovirals for Based on a presentation at prn by Roy M. Gulick, md, mph the Treatment of HIV: Kan Lu, PharmD | Drug Development Fellow University of North Carolina School of Pharmacy Chapel Hill, North Carolina The View in 2006 Roy M. Gulick, md, mph Reprinted from The prn Notebook® | october 2006 | Dr. James F. Braun, Editor-in-Chief Director, Cornell Clinical Trials Unit | Associate Professor of Medicine, Meri D. Pozo, PhD, Managing Editor. Published in New York City by the Physicians’ Research Network, Inc.® Weill Medical College of Cornell University | New York, New York John Graham Brown, Executive Director. For further information and other articles available online, visit http://www.prn.org | All rights reserved. ©october 2006 substantial progress continues to be made in the arena of cokinetics and a long extracellular half-life of approximately 10 hours antiretroviral drug development. prn is again proud to present its annual (Zhu, 2003). During apricitabine’s development, a serious drug interac- review of the experimental agents to watch for in the coming months and tion with lamivudine (Epivir) was noted. Although the plasma years. This year’s review is based on a lecture by Dr. Roy M. Gulick, a long- concentrations of apricitabine were unaffected by coadministration of time friend of prn, and no stranger to the antiretroviral development lamivudine, the intracellular concentrations of apricitabine were reduced pipeline. by approximately sixfold. Additionally, the 50% inhibitory concentration To date, twenty-two antiretrovirals have been approved by the Food (ic50) of apricitabine against hiv with the M184V mutation was increased and Drug Administration (fda) for the treatment of hiv infection. -

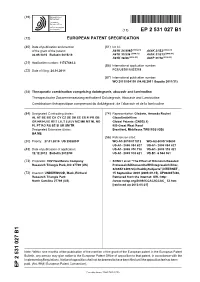

Ep 2531027 B1

(19) TZZ ¥_Z _T (11) EP 2 531 027 B1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (45) Date of publication and mention (51) Int Cl.: of the grant of the patent: A61K 31/4985 (2006.01) A61K 31/52 (2006.01) 06.05.2015 Bulletin 2015/19 A61K 31/536 (2006.01) A61K 31/513 (2006.01) A61K 38/55 (2006.01) A61P 31/18 (2006.01) (21) Application number: 11737484.3 (86) International application number: (22) Date of filing: 24.01.2011 PCT/US2011/022219 (87) International publication number: WO 2011/094150 (04.08.2011 Gazette 2011/31) (54) Therapeutic combination comprising dolutegravir, abacavir and lamivudine Therapeutische Zusammensetzung enthaltend Dolutegravir, Abacavir und Lamivudine Combinaison thérapeutique comprenant du dolutégravir, de l’abacavir et de la lamivudine (84) Designated Contracting States: (74) Representative: Gladwin, Amanda Rachel AL AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB GlaxoSmithKline GR HR HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC MK MT NL NO Global Patents (CN925.1) PL PT RO RS SE SI SK SM TR 980 Great West Road Designated Extension States: Brentford, Middlesex TW8 9GS (GB) BA ME (56) References cited: (30) Priority: 27.01.2010 US 298589 P WO-A1-2010/011812 WO-A2-2009/148600 US-A1- 2006 084 627 US-A1- 2006 084 627 (43) Date of publication of application: US-A1- 2008 076 738 US-A1- 2009 318 421 12.12.2012 Bulletin 2012/50 US-A1- 2009 318 421 US-B1- 6 544 961 (73) Proprietor: VIIV Healthcare Company • SONG1 et al: "The Effect of Ritonavir-Boosted Research Triangle Park, NC 27709 (US) ProteaseInhibitors on the HIV Integrase Inhibitor, S/GSK1349572,in Healthy Subjects", INTERNET , (72) Inventor: UNDERWOOD, Mark, Richard 15 September 2009 (2009-09-15), XP002697436, Research Triangle Park Retrieved from the Internet: URL:http: North Carolina 27709 (US) //www.natap.org/2009/ICCAC/ICCAC_ 52.htm [retrieved on 2013-05-21] Note: Within nine months of the publication of the mention of the grant of the European patent in the European Patent Bulletin, any person may give notice to the European Patent Office of opposition to that patent, in accordance with the Implementing Regulations. -

Synthesis and Development of Long-Acting Abacavir Prodrug Nanoformulations

University of Nebraska Medical Center DigitalCommons@UNMC Theses & Dissertations Graduate Studies Summer 8-19-2016 Synthesis and Development of Long-Acting Abacavir Prodrug Nanoformulations Dhirender Singh University of Nebraska Medical Center Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/etd Part of the Pharmaceutical Preparations Commons, and the Virus Diseases Commons Recommended Citation Singh, Dhirender, "Synthesis and Development of Long-Acting Abacavir Prodrug Nanoformulations" (2016). Theses & Dissertations. 140. https://digitalcommons.unmc.edu/etd/140 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@UNMC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNMC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SYNTHESIS AND DEVELOPMENT OF LONG-ACTING ABACAVIR PRODRUG NANOFORMULATIONS by Dhirender Singh A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School in the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Pharmaceutical Science Under the Supervision of Dr. Howard E. Gendelman University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, Nebraska August 2016 Supervisory Committee: Howard E. Gendelman, M.D. Ram Mahato, Ph.D JoEllyn M. McMillan, Ph.D. David Oupicky, Ph.D SYNTHESIS AND DEVELOPMENT OF LONG-ACTING ABACAVIR PRODRUG NANOFORMULATIONS Dhirender Singh, Ph.D. University of Nebraska Medical Center, 2016 Supervisor: Howard E Gendelman, M.D. Over the past decade, work from our laboratory has demonstrated the potential of targeted nanoformulated antiretroviral therapy (nanoART) to produce sustained high plasma and tissue drug concentrations for weeks following a single intramuscular (IM) administration that can suppress ongoing viral replication and mitigate dose associated viral resistance. -

Current Status and Prospects of HIV Treatment

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Current status and prospects of HIV treatment 1 2 Tomas Cihlar and Marshall Fordyce Current antiviral treatments can reduce HIV-associated at suppressing plasma viremia, and significant progress morbidity, prolong survival, and prevent HIV transmission. has been made toward regimen simplification through the Combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) containing preferably combination of three active drugs into single-tablet regi- three active drugs from two or more classes is required for mens (STRs) (Figure 1) and optimization of drug profiles durable virologic suppression. Regimen selection is based on that maximize long-term tolerability and safety. Lifelong, virologic efficacy, potential for adverse effects, pill burden and chronic therapy without treatment interruption is the dosing frequency, drug–drug interaction potential, resistance standard of care, and the availability of multiple effective test results, comorbid conditions, social status, and cost. With drugs in several classes with differing resistance, safety, prolonged virologic suppression, improved clinical outcomes, and tolerability profiles provides choices after failure of and longer survival, patients will be exposed to antiretroviral first-line treatment. agents for decades. Therefore, maximizing the safety and tolerability of cART is a high priority. Emergence of resistance Herein, we review the current status of antiretroviral and/or lack of tolerability in individual patients require therapy and guidelines for HIV-infected adults, as well availability of a range of treatment options. Development of new as prospects for further innovation in HIV treatment to drugs is focused on improving safety (e.g. tenofovir benefit patients and optimize their long-term health. alafenamide) and/or resistance profile (e.g. -

Background Paper 6.7 Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)/ Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (AIDS)

Priority Medicines for Europe and the World "A Public Health Approach to Innovation" Update on 2004 Background Paper Written by Warren Kaplan Background Paper 6.7 Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)/ Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes (AIDS) By Warren Kaplan, Ph.D., JD, MPH 15 February 2013 Update on 2004 Background Paper, BP 6.7 HIV/AIDS Table of Contents What is new since 2004? ..................................................................................................................................... 4 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 7 2. What are the Epidemiological Trends for Europe and the World? ................................................... 7 2.1 Western and Central Europe ............................................................................................................. 7 2.2 Eastern Europe .................................................................................................................................... 9 2.2 The World (including Europe) ........................................................................................................ 11 3. What is the Control Strategy? Is There an Effective Package of Control Methods Assembled into a “Control Strategy” for Most Epidemiological Settings?................................................................. 13 3.1 Is there a pharmaceutical ‘gap’? .................................................................................................... -

Can the Further Clinical Development of Bevirimat Be Justified?

SwatiCE: Swati; QAD/201969; Total nos of Pages: 2; QAD 201969 EDITORIAL COMMENT Can the further clinical development of bevirimat be justified? Mark A. Wainberga and Jan Albertb AIDS 2010, 24:000–000 Keywords: bevirimat, protease inhibitor resistance HIV-infected patients who fail standard therapeutic Not surprisingly, however, HIV resistance against BVM regimens are in need of new drugs that will remain has been selected in tissue culture. Mutations responsible active against drug-resistant viral variants. There is a for resistance have been identified within flanking constant need to develop new compounds that will not be sequences of the p24/p2 cleavage site and have been compromised by problems of cross-resistance, as so often confirmed as possessing biological relevance by site- occurs among members of the same family of drugs, for directed mutagenesis [3]. These mutations can sometimes example, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors interfere with the ability of BVM to bind to its target, (NRTIs), nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors although, in most cases, increased cleavage efficiency at (NNRTIs), and protease inhibitors. Indeed, successful the p24/p2 junction may also occur [3,4]. second-line and salvage regimens will commonly include members of drug classes to which a patient has not Recent results have revealed that naturally occurring previously been exposed, for example, a protease inhibi- polymorphisms located within p2, close to the p24 tor and an integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI) in cleavage site, may be present in some individuals, the case of an individual who began therapy with two resulting in lower BVM anti-HIV efficacy. In addition, NRTIs and a NNRTI, as well as the use of fusion clinical investigators have long suspected that BVM might inhibitors, for example, enfuvirtide, and CCR5 antago- potentially be less effective in the treatment of patients nists, for example, maraviroc. -

NRTI Toxicity Francois Venter Wits Reproductive Health & HIV Institute

NRTI toxicity Francois Venter Wits Reproductive Health & HIV Institute Pipeline Report http://www.pipelinereport.org So what we got? Current and Investigational Antiretrovirals NRTIs/NtRTI NNRTI PI Integrase In Abacavir Doravirine Atazanavir Cabotegravir Didanosine Efavirenz Darunavir Dolutegravir Emtricitabine Etravirine Fosamprenavir Elvitegravir Lamivudine Nevirapine Indinavir Raltegravirr Stavudine Rilpivirine Lopinavir/r Tenofovir Fixed Combo Nelfinavir Tenofovir AF MI AZT/3TC Ritonavir Zidovudine Saquinavir ABC/3TC Bevirimat Tipranavir TDF/FTC BMS-955176 CYP3A4 In AZT/3TC/ABC EI/FI Cobicistat TDF/FTC/EFV Enfuvirtide TDF/FTC/RPV Maraviroc TDF/FTC/ETG/COB BMS-663068 Thanks Howard Kessler ABC/3TC/DTG TAF/FTC/ETG/COB • 28 approved drugs, 5 classes • Up to 10 recommended first-line regimens • BUT: only 4 NRTIs that matter (if leave out 3TC/FTC) An aside… • Nuke free/sparing initial ART NNRTI 1 PI + 1 NNRTI Efavirenz INSTI PI 1 PI + 1 INSTI Raltegravir Atazanavir/r Darunavir/r Lopinavir/r NRTI 1 PI + 1 NRTI Lamivudine FI 1 PI + 1 FI Maraviroc Nuke free/sparing initial ART Study Regimen Comparison Efficacy SPARTAN ATV/r + RAL ATV/r + TDF-FTC HIV-RNA <50 at wk 24: 74.6% vs 63.3% non-inferior (but high bilirubinemia and resistance to RAL) A4001078 ATV/r + MVC ATV/r + TDF-FTC HIV-RNA <50 at wk 48: 74.6% vs 83.6% non-inferior NEAT001/ DRV/r + RAL DRV/r + TDF-FTC Virological or clinical failure at wk 96: ANRS143 17.8% vs 13.8% non-inferior significantly inferior to standard therapy if CD4 <200/ml; trend for >100 000 c/mL MODERN DRV/r + MVC -

Antiviral Drugs in the Treatment of Aids: What Is in the Pipeline ?

October 15, 2007 EU RO PE AN JOUR NAL OF MED I CAL RE SEARCH 483 Eur J Med Res (2007) 12: 483-495 © I. Holzapfel Publishers 2007 ANTIVIRAL DRUGS IN THE TREATMENT OF AIDS: WHAT IS IN THE PIPELINE ? Hans-Jürgen Stellbrink Infektionsmedizinisches Centrum Hamburg ICH, Hamburg, Germany Abstract even targeting immune responses have to be devel- Drug development in the field of HIV treatment is oped. Continued drug development serves the ulti- rapid. New nucleoside analogues (NRTI), non-nucleo- mate goal of normalization of life expectancy. side analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNR- TI), and protease inhibitors (PI) are currently being in- METHODS vestigated in human trials. Furthermore, inhibitors of HIV attachment, fusion and integrase with novel Drug development in the field of HIV infection is modes of action are being developed, which offer new highly competitive, and a company’s decision to pur- perspectives for the goal of a normalization of life-ex- sue or discontinue the development of a drug is dri- pectancy in HIV-infected individuals. The most ad- ven by economic rather than scientific considerations. vanced compounds likely to become licensed soon in- Of all candidate compounds, only a few reach the lev- clude the NNRTIs rilpivirine and etravirine, the inte- el of trials in humans, and some exhibit lack of effica- grase inhibitors raltegravir and elvitegravir, and mar- cy or toxicity problems at this stage. Some compounds aviroc and vicriviroc, novel inhibitors of the CCR5 also have no obvious advantage over currently avail- chemokine receptor, which functions as the major able ones, so that their development is discontinued. -

PATHOLOGY of HIV/AIDS 32Nd Edition

PATHOLOGY OF HIV/AIDS 32nd Edition by Edward C. Klatt, MD Professor of Pathology Department of Biomedical Sciences Mercer University School of Medicine Savannah, Georgia, USA July 20, 2021 Copyright © by Edward C. Klatt, MD All rights reserved worldwide 2 DEDICATION To persons living with HIV/AIDS past, present, and future who provide the knowledge, to researchers who utilize the knowledge, to health care workers who apply the knowledge, and to public officials who do their best to promote the health of their citizens with the knowledge of the biology, pathophysiology, treatment, and prevention of HIV/AIDS. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS 3.................................................................................................................................2 CHAPTER 1 - BIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS OF HIV INFECTION.....6 INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................................6 BIOLOGY OF HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS................................................10 HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS SUBTYPES.....................................................29 OTHER HUMAN RETROVIRUSES....................................................................................31 EPIDEMIOLOGY OF HIV/AIDS.........................................................................................36 RISK GROUPS FOR HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS INFECTION.............46 NATURAL HISTORY OF HIV INFECTION......................................................................47 PROGRESSION OF HIV -

Repurposing of FDA Approved Drugs

Antiviral Drugs (In Phase IV) ABACAVIR GEMCITABINE ABACAVIR SULFATE GEMCITABINE HYDROCHLORIDE ACYCLOVIR GLECAPREVIR ACYCLOVIR SODIUM GRAZOPREVIR ADEFOVIR DIPIVOXIL IDOXURIDINE AMANTADINE IMIQUIMOD AMANTADINE HYDROCHLORIDE INDINAVIR AMPRENAVIR INDINAVIR SULFATE ATAZANAVIR LAMIVUDINE ATAZANAVIR SULFATE LEDIPASVIR BALOXAVIR MARBOXIL LETERMOVIR BICTEGRAVIR LOPINAVIR BICTEGRAVIR SODIUM MARAVIROC BOCEPREVIR MEMANTINE CAPECITABINE MEMANTINE HYDROCHLORIDE CARBARIL NELFINAVIR CIDOFOVIR NELFINAVIR MESYLATE CYTARABINE NEVIRAPINE DACLATASVIR OMBITASVIR DACLATASVIR DIHYDROCHLORIDE OSELTAMIVIR DARUNAVIR OSELTAMIVIR PHOSPHATE DARUNAVIR ETHANOLATE PARITAPREVIR DASABUVIR PENCICLOVIR DASABUVIR SODIUM PERAMIVIR DECITABINE PERAMIVIR DELAVIRDINE PIBRENTASVIR DELAVIRDINE MESYLATE PODOFILOX DIDANOSINE RALTEGRAVIR DOCOSANOL RALTEGRAVIR POTASSIUM DOLUTEGRAVIR RIBAVIRIN DOLUTEGRAVIR SODIUM RILPIVIRINE DORAVIRINE RILPIVIRINE HYDROCHLORIDE EFAVIRENZ RIMANTADINE ELBASVIR RIMANTADINE HYDROCHLORIDE ELVITEGRAVIR RITONAVIR EMTRICITABINE SAQUINAVIR ENTECAVIR SAQUINAVIR MESYLATE ETRAVIRINE SIMEPREVIR FAMCICLOVIR SIMEPREVIR SODIUM FLOXURIDINE SOFOSBUVIR FOSAMPRENAVIR SORIVUDINE FOSAMPRENAVIR CALCIUM STAVUDINE FOSCARNET TECOVIRIMAT FOSCARNET SODIUM TELBIVUDINE GANCICLOVIR TENOFOVIR ALAFENAMIDE GANCICLOVIR SODIUM TENOFOVIR ALAFENAMIDE FUMARATE TIPRANAVIR VELPATASVIR TRIFLURIDINE VIDARABINE VALACYCLOVIR VOXILAPREVIR VALACYCLOVIR HYDROCHLORIDE ZALCITABINE VALGANCICLOVIR ZANAMIVIR VALGANCICLOVIR HYDROCHLORIDE ZIDOVUDINE Antiviral Drugs (In Phase III) ADEFOVIR LANINAMIVIR OCTANOATE -

NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Bioorg Med Chem Lett

NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Bioorg Med Chem Lett. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2013 August 15. NIH-PA Author ManuscriptPublished NIH-PA Author Manuscript in final edited NIH-PA Author Manuscript form as: Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2012 August 15; 22(16): 5190–5194. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.06.080. Synthesis of Betulinic Acid Derivatives as Entry Inhibitors against HIV-1 and Bevirimat-Resistant HIV-1 Variants Zhao Danga, Keduo Qianb, Phong Hoa, Lei Zhua, Kuo-Hsiung Leeb,c, Li Huanga,*, and Chin- Ho Chena,* aSurgical Science, Department of Surgery, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina 27710, United States bNatural Products Research Laboratories, Eshelman School of Pharmacy, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27599, United States cChinese Medicine Research and Development Center, China Medical University and Hospital, Taichung, Taiwan Abstract Betulinic acid derivatives modified at the C28 position are HIV-1entry inhibitors such as compound A43D; however, modified at the C3 position instead of C28 give HIV-1 maturation inhibitor such as bevirimat. Bevirimat exhibited promising pharmacokinetic profiles in clinical trials, but its effectiveness was compromised by the high baseline drug resistance of HIV-1 variants with polymorphism in the putative drug binding site. In an effort to determine whether the viruses with bevirimat resistant polymorphism also altered their sensitivities to the betulinic acid derivatives that inhibit HIV-1 entry, a series of new betulinic acid entry inhibitors were synthesized and tested for their activities against HIV-1 NL4-3 and NL4-3 variants resistant to bevirimat. The results show that the bevirimat resistant viruses were approximately 5- to10-fold more sensitive to three new glutamine ester derivatives (13, 15 and 38) and A43D in an HIV-1 multi-cycle replication assay. -

TABLE 2. HIV Treatment Pipeline 2003–2012 Class Drug Name Generic Name Brand Name Sponsor 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2

TABLE 2. HIV Treatment Pipeline 2003–2012 Class Drug name Generic name Brand name Sponsor 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 NRTI FTC emtricitabine Emtriva (2003) Triangle/Gilead approved NRTI AG1549 capravirine Agouron/Pfizer III III discontinued NRTI DAPD amdoxovir Gilead/Emory/RFS Pharma II to Emory to RFS II II II II discontinued NRTI MIV-310, FLT alovudine Boehringer Ingelheim/Medivir/Beijing Mefuvir II to Mefuvir NRTI ACH-126443 elvucitabine Achillion II II II I II NRTI D-d4FC, DPC-817 reverset Pharmasset/Incyte I I II discontinued NRTI SPD-754, AVX-754, ATC apricitabine Shire BioChem/Avexa I I I II II II discontinued NRTI racivir Pharmasset I I II discontinued NRTI 4’-Ed4T, OBP-601 (ex festinavir) BMS-986001 Bristol-Myers Squibb II II NRTI CMX-157 Chimerix I NtRTI GS-7340, PMPA Gilead II II NNRTI TMC-125 etravirine Intelence (2008) Janssen (ex Tibotec) II II II III III approved NNRTI calanolide A Advanced Life Sciences/Sarawak MediChem II II NNRTI DPC-083, AI-183 Bristol-Myers Squibb II discontinued NNRTI TMC-278 rilpivirine Edurant (2011) Janssen (ex Tibotec) I II III III III III approved NNRTI BILR-355/r BS Boehringer Ingelheim I II discontinued NNRTI UK-453061 lersivirine Pfizer II II II II NNRTI Viramune XR (2011) Boehringer Ingelheim approved NNRTI (injectable) rilpivirine-LA Janssen (ex Tibotec) I PI atazanavir Reyataz (2003) Bristol-Myers Squibb approved PI VX-175, GW-433908 fosamprenavir Lexiva (2003) Vertex/GlaxoSmithKline approved PI tipranavir Aptivus (2005) Boehringer Ingelheim III III approved PI TMC-114