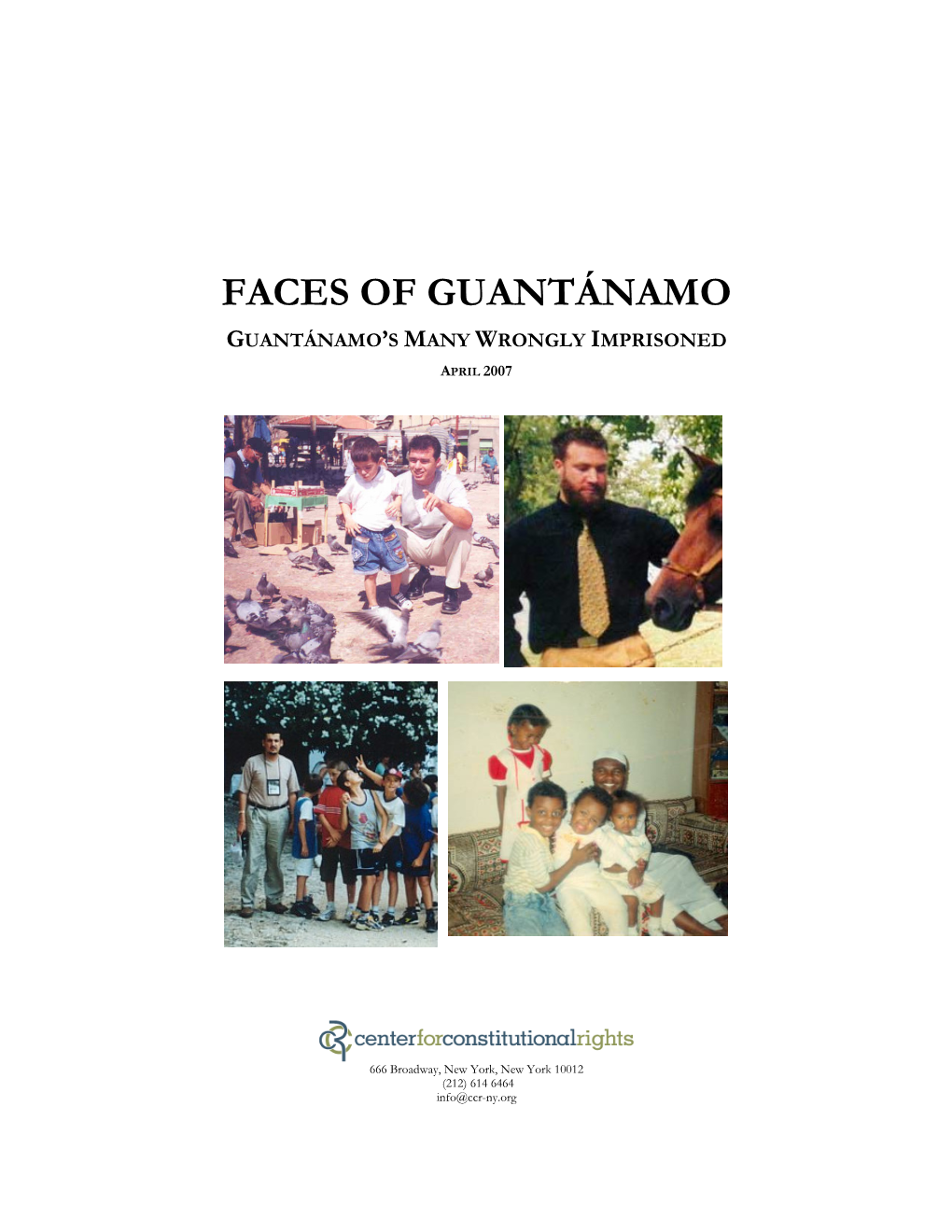

Faces of Guantánamo Guantánamo ’S Many Wrongly Imprisoned

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Supreme Court of the United States

No. ________ In the Supreme Court of the United States KHALED A. F. AL ODAH, ET AL., PETITIONERS, v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ET AL., RESPONDENTS. ON PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI DAVID J. CYNAMON THOMAS B. WILNER MATTHEW J. MACLEAN COUNSEL OF RECORD OSMAN HANDOO NEIL H. KOSLOWE PILLSBURY WINTHROP AMANDA E. SHAFER SHAW PITTMAN LLP SHERI L. SHEPHERD 2300 N Street, N.W. SHEARMAN & STERLING LLP Washington, DC 20037 801 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W. 202-663-8000 Washington, DC 20004 202-508-8000 GITANJALI GUTIERREZ J. WELLS DIXON GEORGE BRENT MICKUM IV SHAYANA KADIDAL SPRIGGS & HOLLINGSWORTH CENTER FOR 1350 “I” Street N.W. CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS Washington, DC 20005 666 Broadway, 7th Floor 202-898-5800 New York, NY 10012 212-614-6438 Counsel for Petitioners Additional Counsel Listed on Inside Cover JOSEPH MARGULIES JOHN J. GIBBONS MACARTHUR JUSTICE CENTER LAWRENCE S. LUSTBERG NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY GIBBONS P.C. LAW SCHOOL One Gateway Center 357 East Chicago Avenue Newark, NJ 07102 Chicago, IL 60611 973-596-4500 312-503-0890 MARK S. SULLIVAN BAHER AZMY CHRISTOPHER G. KARAGHEUZOFF SETON HALL LAW SCHOOL JOSHUA COLANGELO-BRYAN CENTER FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE DORSEY & WHITNEY LLP 833 McCarter Highway 250 Park Avenue Newark, NJ 07102 New York, NY 10177 973-642-8700 212-415-9200 DAVID H. REMES MARC D. FALKOFF COVINGTON & BURLING COLLEGE OF LAW 1201 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W. NORTHERN ILLINOIS Washington, DC 20004 UNIVERSITY 202-662-5212 DeKalb, IL 60115 815-753-0660 PAMELA CHEPIGA SCOTT SULLIVAN ANDREW MATHESON DEREK JINKS KAREN LEE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS SARAH HAVENS SCHOOL OF LAW ALLEN & OVERY LLP RULE OF LAW IN WARTIME 1221 Avenue of the Americas PROGRAM New York, NY 10020 727 E. -

Murat Kurnaz Released from Guantánamo!

Amnesty International 25 August 2006 AI Index AMR 51/147/2006 Murat Kurnaz had been held for four years and eight months without charge or trial. Guantánamo must be closed! Good News: Murat Kurnaz released from Guantánamo! “Thank God, I am well, but just God that created us knows when I will come back” Murat Kurnaz wrote these words to his family from Guantánamo in March 2002. His dreams of returning home to Germany have only now, finally, been realised. Released from Guantánamo on 24 August 2006, Murat Kurnaz had been held for four years and eight months without charge or trial. The only contact he had been allowed with his family was through heavily censored letters. In a statement, his German lawyer said: “He is now again in the circle of his family. Their joy at embracing their lost son again is indescribable”. Murat’s mother, Rabiye Kurnaz has dedicated these past years to campaigning for her eldest son’s release. In November 2005 she attended an international conference organized by Amnesty International and Reprieve where she spoke of her hopes of being reunited with her son. Now these hopes have become a reality. Murat Kuraz is a Turkish national who was born in Germany in 1982. His prolonged detention in Guantánamo had been complicated by his status – lacking German citizenship, the German authorities had refused his return to Germany. The Turkish authorities had shown little interest in his case. It was only after intense lobbying from his family, lawyers and AI members around the world, including in his home town of Bremen, that the German authorities began to act on his behalf, finally paving the way for his return. -

1. October 19, 2011 To: Robert Nicholson, Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada Re: Letter in Support of Private

October 19, 2011 To: Robert Nicholson, Minister of Justice and Attorney General of Canada Re: Letter in Support of Private Prosecutions Filed Against George W. Bush for Torture We, the undersigned human rights non-governmental organizations and individuals, are writing this statement in full support of the private prosecutions against George W. Bush, former President of the United States, being lodged on behalf of three former Guantánamo detainees, and one current detainee, who allege that they were tortured by U.S. officials, and seek a criminal investigation and prosecution against Mr. Bush upon arrival in Canada, for substantive breaches of the Canadian Criminal Code and United Nations Convention Against Torture (CAT). The criminal cases submitted under sections 504, 269.1, 21 and 22 of the Canadian Criminal Code, and the Indictment with an appendix of supporting material attached thereto, (collectively, the “Bush Dossiers”) set forth reasonable and probable grounds to believe that a person who is scheduled to be present on Canadian territory has committed an act of torture. The Case Against George W. Bush The Bush Dossiers allege that George W. Bush, in his capacity of former president of the United States, bears individual responsibility for acts of torture and/or cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment committed against detainees held in U.S. custody or rendered to other countries by the U.S., in that he ordered, authorized, condoned, planned or otherwise aided and abetted such acts, or failed to prevent or punish subordinates for the commission of such acts. As set forth in detail in the Bush Dossiers, including through documentary evidence in the form of inter alia official memoranda issued by Mr. -

Massacre of Hazaras in Afghanistan

1 Genocide OF Hazaras In Afghanistan By TALIBAN Compiled by: M.A. Gulzari 5th March 2001 2 To those innocents, who killed by Taliban. A Hazara Hanged publicaly in Heart Bazar 3 CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 Massacres of Mazar Eyewitness………………………………………………………………………………… ……….4 MASSCRES OF MAZAR SHARIF………………………………….8 I. SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS .........................................................................12 BACKGROUND ......................................................................................................................16 III. THE FIRST DAY OF THE TAKEOVER ...........................................................................18 8 The Taliban fly white flags from their vehicles.......................................................................23 V. ABDUCTIONS OF AND ASSAULTS ON WOMEN..........................................................24 V. ABDUCTIONS OF AND ASSAULTS ON WOMEN..........................................................25 VI. DETENTIONS OF PERSONS TRYING TO LEAVE.........................................................26 II. ATTACKS ON CIVILIANS FLEEING MAZAR.................................................................27 VII. THE APPLICABLE LAW.................................................................................................28 VIII. THE TALIBAN’S REPRESSIVE SOCIAL POLICIES....................................................29 IX. CONCLUSION...................................................................................................................30 CHAPTER2……………………………………………………………………………… -

Avertissement Liens

AVERTISSEMENT Ce document est le fruit d’un long travail approuvé par le jury de soutenance et mis à disposition de l’ensemble de la communauté universitaire élargie. Il est soumis à la propriété intellectuelle de l’auteur : ceci implique une obligation de citation et de référencement lors de l’utilisation de ce document. D’autre part, toute contrefaçon, plagiat, reproduction illicite de ce travail expose à des poursuites pénales. Contact : [email protected] LIENS Code la Propriété Intellectuelle – Articles L. 122-4 et L. 335-1 à L. 335-10 Loi n°92-597 du 1er juillet 1992, publiée au Journal Officiel du 2 juillet 1992 http://www.cfcopies.com/V2/leg/leg-droi.php http://www.culture.gouv.fr/culture/infos-pratiques/droits/protection.htm ����� ������������������������� ������������������������������������� ������������� Université Toulouse 1 Capitole (UT1 Capitole) ��������������������������� M. Haroon MANNANI le 11 juillet 2014 ������� � La reconstruction de l'État-Nation en Afghanistan �������������� et �discipline ou spécialité � � ED SJP : Sciences Politiques �������������������� Centre Toulousain d'Histoire du Droit et des Idées Politiques (CTHDIP) ���������������������������� Mme DANIELLE CABANIS, professeur des universités Université Toulouse 1 Jury: M. FARKHAD ALIMUKHAMEDOV, professeur Université d'Ankara - Rapporteur du jury M. FRANÇOIS-PAUL BLANC, professeur émérite Université de Perpignan - Rapporteur du jury Mme DANIELLE CABANIS, professeur des universités Université Toulouse 1 - Directeur de recherches M. JEAN-MARIE -

The Wire USA Executes Mentally

The Wire March 2006 Vol. 36. No. 02 AI Index: NWS 21/002/2006 [Page 1] USA executes mentally ill “Today, at 6pm, the State of Florida is scheduled to kill my brother, Thomas Provenzano, despite clear evidence that he is mentally ill... I have to wonder: Where is the justice in killing a sick human being?” Sister of death row inmate, June 2000 By the end of 2005, more than 1,000 men and women had been put to death in the USA since executions resumed in 1977. At least one in 10 of them were suffering from mental illness. In a report released in January, AI listed the stories of a hundred people who had been executed in the USA since 1977 despite clear evidence that they were mentally ill. People like Johnny Garrett, executed in 1992 for a murder committed when he was 17. Like many on the list, Johnny Garrett was severely physically and sexually abused as a child, leaving him brain damaged and chronically psychotic. He was described by a psychiatrist as “one of the most psychiatrically impaired inmates” she had ever examined, and by a psychologist as having “one of the most virulent histories of abuse and neglect... encountered in over 28 years of practice.” Many of the 100 suffered hallucinations or delusions as a result of their mental illness, some had serious brain damage. Yet all were judged mentally competent and able to understand the charges against them – a necessary prerequisite for a death sentence. The judge who found Thomas Provenzano competent for execution found “clear and convincing evidence that Provenzano has a delusional -

United States District Court for the District of Columbia

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ) SHAFIQ RASUL, et al. ) ) Petitioners, ) ) v. ) Civil Action No. 02-CV-0299 (CKK) ) GEORGE WALKER BUSH, ) President of the United States, et al., ) ) Respondents. ) ) ) FAWZI KHALID ABDULLAH FAHAD ) AL ODAH, et al. ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) v. ) Civil Action No. 02-CV-0828 (CKK) ) UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) et al., ) ) Defendants. ) ) ) MAMDOUH HABIB, et al., ) ) Petitioners, ) ) v. ) Civil Action No. 02-CV-1130 (CKK) ) GEORGE WALKER BUSH, ) President of the United States, et al., ) ) Respondents. ) ) ) MURAT KURNAZ, et al., ) ) Petitioners, ) v. ) Civil Action No. 04-CV-1135 (ESH) ) GEORGE W. BUSH, ) President of the United States, et al., ) ) Respondents. ) ) ) OMAR KHADR, et al., ) ) Petitioners, ) v. ) Civil Action No. 04-CV-1136 (JDB) ) GEORGE W. BUSH, ) President of the United States, et al., ) ) Respondents. ) ) ) MOAZZAM BEGG, et al., ) ) Petitioners, ) v. ) Civil Action No. 04-CV-1137 (RMC) ) GEORGE W. BUSH, ) President of the United States, et al., ) ) Respondents. ) ) ) MOURAD BENCHELLALI, et al., ) ) Petitioners, ) v. ) Civil Action No. 04-CV-1142 (RJL) ) GEORGE W. BUSH, ) President of the United States, et al., ) ) Respondents. ) ) ) JAMIL EL-BENNA, et al., ) ) Petitioners, ) v. ) Civil Action No. 04-CV-1144 (RWR) ) GEORGE W. BUSH, ) President of the United States, et al., ) ) Respondents. ) ) ) FALEN GHEREBI, et al., ) ) Petitioners, ) v. ) Civil Action No. 04-CV-1164 (RBW) ) GEORGE W. BUSH, ) President of the United States, et al., ) ) Respondents. ) ) ) LAKHDAR BOUMEDIENE, et al.,) ) Petitioners, ) v. ) Civil Action No. 04-CV-1166 (RJL) ) GEORGE W. BUSH, ) President of the United States, et al., ) ) Respondents. ) ) ) SUHAIL ABDUL ANAM, et al., ) ) Petitioners, ) v. ) Civil Action No. -

The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: an Empirical Study

© Reuters/HO Old – Detainees at XRay Camp in Guantanamo. The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empirical Study Benjamin Wittes and Zaahira Wyne with Erin Miller, Julia Pilcer, and Georgina Druce December 16, 2008 The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empiricial Study Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Introduction 3 The Public Record about Guantánamo 4 Demographic Overview 6 Government Allegations 9 Detainee Statements 13 Conclusion 22 Note on Sources and Methods 23 About the Authors 28 Endnotes 29 Appendix I: Detainees at Guantánamo 46 Appendix II: Detainees Not at Guantánamo 66 Appendix III: Sample Habeas Records 89 Sample 1 90 Sample 2 93 Sample 3 96 The Current Detainee Population of Guantánamo: An Empiricial Study EXECUTIVE SUMMARY he following report represents an effort both to document and to describe in as much detail as the public record will permit the current detainee population in American T military custody at the Guantánamo Bay Naval Station in Cuba. Since the military brought the first detainees to Guantánamo in January 2002, the Pentagon has consistently refused to comprehensively identify those it holds. While it has, at various times, released information about individuals who have been detained at Guantánamo, it has always maintained ambiguity about the population of the facility at any given moment, declining even to specify precisely the number of detainees held at the base. We have sought to identify the detainee population using a variety of records, mostly from habeas corpus litigation, and we have sorted the current population into subgroups using both the government’s allegations against detainees and detainee statements about their own affiliations and conduct. -

Contents EDITORIAL, POLITICAL ANALYSIS, 3 a Quarterly Publication of MILITARY REPORT

AECHAN JEHAD Contents EDITORIAL, POLITICAL ANALYSIS, 3 A Quarterly Publication of MILITARY REPORT, The Cultural Council of Grand table of Afghanwar casualties Afghanistan Resistance (April -June, 1988) Afghans and the Geneva accordon Afghanistan 14 MANAGING EDITOR: ® MAJOR DOCUMENTS: 21 Sabahuddin Kushkaki 1. Text of charter for mujaheddin transitional April-June, 1908 government; (2) Text of Geneva accord on Afghan- istan; (3) IUAM and the Geneva accord; (4) Muja- SUBSCRIPTION heddin offer general amnesty; (5) IUAM President urges trial for PDPA high brass; (6) Biographies Per Six Annual of IUAM transitional cabinet; (7) Biographies of copy months three IUAM leaders; (8) Charters of the IUAM Pakistaa organizations; (9) Annual report of Amnesty In- (Ra.) 30 60 110 ternational on Afghanistan, Foreign AFUHANISTAN IN INTERNATIONAL FORUMS: (s) 6 12 30 1« Islamabad Conference on Afghan future 2. Karachi Islamic meeting 3. Paris Conference: Afghan Agriculture Cultural Council of Afghanist- 0 IRC Survey on health in Afghan refugeecamps.97 Resistance CATALOGUE OF MUJAHEDDIN PRESS House No.8861 St. No. 27, G /9 -1 99 103 Islamabad, Pakistan 0 DIGEST OF MUJAHEDDIN PRESS Telephone 853797 (APRIL-JUNE 1988) ® BOOKS BY THE MUJAHEDDIN, FOR THE 164 MUJAHEDDIN 0 CHRONOLOGY OF AFGHAN EVENTS 168 (APRIL-JUNE 1988) 0 AFGHAN ISSUES COVERAGE: 318 By Radio Kabul, Radio Moscow (April -June, 1988) 0 MAPS 319 -320 0 ABBREVIATIONSLIST 321 FROM MUJAHEDDIN PUBLICATIONS MA Juiacst-- April -June, 19 88 Vol.1, No.4 AFGHAN JEHAD Editorial Q o c':. NC(° IN ME NAME OF GOD, MOST GRACICJUS, MOST MERCI.FU AFTER GENEVA Now that the Russian troops are on than way out from Afghanistan,' the focus on the Afghanistan issue is on two subjects; the nature of government in Kabul and finding a channel for the huge humanitarian assistance which the international community has indicated will provide to the war,ravaged Afghan- istan after the Soviet. -

Supreme Court of the United States Supreme Court Of

No. 06- IN THE Supreme Court of the United States LAKHDAR BOUMEDIENE, et al., Petitioners, v. GEORGE W. BUSH, et al., Respondents. ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI STEPHEN H. OLESKEY SETH P. WAXMAN ROBERT C. KIRSCH Counsel of Record MARK C. FLEMING PAUL R.Q. WOLFSON JOSEPH J. MUELLER WILMER CUTLER PICKERING PRATIK A. SHAH HALE AND DORR LLP LYNNE CAMPBELL SOUTTER 1875 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W. JEFFREY S. GLEASON Washington, DC 20006 LAUREN G. BRUNSWICK (202) 663-6000 WILMER CUTLER PICKERING HALE AND DORR LLP DOUGLAS F. CURTIS 60 State Street PAUL M. WINKE Boston, MA 02109 JULIAN DAVIS MORTENSON (617) 526-6000 WILMER CUTLER PICKERING HALE AND DORR LLP 399 Park Avenue New York, NY 10022 (212) 230-8800 PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/074717/ QUESTIONS PRESENTED 1. Whether the Military Commissions Act of 2006, Pub. L. No. 109-366, 120 Stat. 2600, validly stripped federal court jurisdiction over habeas corpus petitions filed by for- eign citizens imprisoned indefinitely at the United States Naval Station at Guantanamo Bay. 2. Whether Petitioners’ habeas corpus petitions, which establish that the United States government has im- prisoned Petitioners for over five years, demonstrate unlaw- ful confinement requiring the grant of habeas relief or, at least, a hearing on the merits. (i) PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/074717/ LIST OF PARTIES TO PROCEEDING BELOW The parties to the proceeding in the court of appeals (Boumediene, et al. -

The Constitutional and Political Clash Over Detainees and the Closure of Guantanamo

UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH LAW REVIEW Vol. 74 ● Winter 2012 PRISONERS OF CONGRESS: THE CONSTITUTIONAL AND POLITICAL CLASH OVER DETAINEES AND THE CLOSURE OF GUANTANAMO David J.R. Frakt ISSN 0041-9915 (print) 1942-8405 (online) ● DOI 10.5195/lawreview.2012.195 http://lawreview.law.pitt.edu This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. This site is published by the University Library System of the University of Pittsburgh as part of its D- Scribe Digital Publishing Program and is cosponsored by the University of Pittsburgh Press. PRISONERS OF CONGRESS: THE CONSTITUTIONAL AND POLITICAL CLASH OVER DETAINEES AND THE CLOSURE OF GUANTANAMO David J.R. Frakt Table of Contents Prologue ............................................................................................................... 181 I. Introduction ................................................................................................. 183 A. A Brief Constitutional History of Guantanamo ................................... 183 1. The Bush Years (January 2002 to January 2009) ....................... 183 2. The Obama Years (January 2009 to the Present) ........................ 192 a. 2009 ................................................................................... 192 b. 2010 to the Present ............................................................. 199 II. Legislative Restrictions and Their Impact ................................................... 205 A. Restrictions on Transfer and/or Release -

Stephen Oleskey Written Testimony House Oversight Comm 05-06-08

TESTIMONY OF STEPHEN H. OLESKEY OF WILMER CUTLER PICKERING HALE AND DORR LLP, COUNSEL FOR SIX GUANTANAMO DETAINEES CITY ON THE HILL OR PRISON ON THE BAY? THE MISTAKES OF GUANTANAMO AND THE DECLINE OF AMERICA’S IMAGE BEFORE THE HOUSE SUBCOMMITTEE ON FOREIGN AFFAIRS SUBCOMMITTEE ON INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND OVERSIGHT MAY 6, 2008 Introduction Thank you Chairman Delahunt, Ranking Member Rohrabacher, and Members of the House Committee on Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on International Organizations, Human Rights, and Oversight for inviting me to speak to you today on this important issue. All counsel to Guantanamo detainees are grateful for the time, energy and thought which this Subcommittee is devoting to consideration of the issues presented by the detention of our clients, who have now been detained at Guantanamo Bay for almost six years and four months. My name is Stephen H. Oleskey and I am a partner at the law firm of Wilmer Cutler Pickering Hale and Dorr. I have been a member of the Massachusetts Bar since 1968 and am also admitted in New York and New Hampshire. I previously served as Massachusetts Deputy Attorney General and Chief of that office’s Public Protection Bureau. My practice generally focuses on complex civil litigation. By way of background to today’s testimony, my experience in the critical matter before this Committee arises from my role as co-lead counsel and pro bono advocate for six Guantanamo detainees in the period since July 2004, following the decisions of the United States Supreme Court in the Rasul and Hamdi cases.