Chapter 4. Acids and Bases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Choosing Buffers Based on Pka in Many Experiments, We Need a Buffer That Maintains the Solution at a Specific Ph. We May Need An

Choosing buffers based on pKa In many experiments, we need a buffer that maintains the solution at a specific pH. We may need an acidic or a basic buffer, depending on the experiment. The Henderson-Hasselbalch equation can help us choose a buffer that has the pH we want. pH = pKa + log([conj. base]/[conj. acid]) With equal amounts of conjugate acid and base (preferred so buffers can resist base and acid equally), then … pH = pKa + log(1) = pKa + 0 = pKa So choose conjugates with a pKa closest to our target pH. Chemistry 103 Spring 2011 Example: You need a buffer with pH of 7.80. Which conjugate acid-base pair should you use, and what is the molar ratio of its components? 2 Chemistry 103 Spring 2011 Practice: Choose the best conjugate acid-base pair for preparing a buffer with pH 5.00. What is the molar ratio of the buffer components? 3 Chemistry 103 Spring 2011 buffer capacity: the amount of strong acid or strong base that can be added to a buffer without changing its pH by more than 1 unit; essentially the number of moles of strong acid or strong base that uses up all of the buffer’s conjugate base or conjugate acid. Example: What is the capacity of the buffer solution prepared with 0.15 mol lactic acid -4 CH3CHOHCOOH (HA, Ka = 1.0 x 10 ) and 0.20 mol sodium lactate NaCH3CHOHCOO (NaA) and enough water to make 1.00 L of solution? (from previous lecture notes) 4 Chemistry 103 Spring 2011 Review of equivalence point equivalence point: moles of H+ = moles of OH- (moles of acid = moles of base, only when the acid has only one acidic proton and the base has only one hydroxide ion). -

Is There an Acid Strong Enough to Dissolve Glass? – Superacids

ARTICLE Is there an acid strong enough to dissolve glass? – Superacids For anybody who watched cartoons growing up, the word unit is based on how acids behave in water, however as acid probably springs to mind images of gaping holes being very strong acids react extremely violently in water this burnt into the floor by a spill, and liquid that would dissolve scale cannot be used for the pure ‘common’ acids (nitric, anything you drop into it. The reality of the acids you hydrochloric and sulphuric) or anything stronger than them. encounter in schools, and most undergrad university Instead, a different unit, the Hammett acidity function (H0), courses is somewhat underwhelming – sure they will react is often preferred when discussing superacids. with chemicals, but, if handled safely, where’s the drama? A superacid can be defined as any compound with an People don’t realise that these extraordinarily strong acids acidity greater than 100% pure sulphuric acid, which has a do exist, they’re just rarely seen outside of research labs Hammett acidity function (H0) of −12 [1]. Modern definitions due to their extreme potency. These acids are capable of define a superacid as a medium in which the chemical dissolving almost anything – wax, rocks, metals (even potential of protons is higher than it is in pure sulphuric acid platinum), and yes, even glass. [2]. Considering that pure sulphuric acid is highly corrosive, you can be certain that anything more acidic than that is What are Superacids? going to be powerful. What are superacids? Its all in the name – super acids are intensely strong acids. -

The Strongest Acid Christopher A

Chemistry in New Zealand October 2011 The Strongest Acid Christopher A. Reed Department of Chemistry, University of California, Riverside, California 92521, USA Article (e-mail: [email protected]) About the Author Chris Reed was born a kiwi to English parents in Auckland in 1947. He attended Dilworth School from 1956 to 1964 where his interest in chemistry was un- doubtedly stimulated by being entrusted with a key to the high school chemical stockroom. Nighttime experiments with white phosphorus led to the Headmaster administering six of the best. He obtained his BSc (1967), MSc (1st Class Hons., 1968) and PhD (1971) from The University of Auckland, doing thesis research on iridium organotransition metal chemistry with Professor Warren R. Roper FRS. This was followed by two years of postdoctoral study at Stanford Univer- sity with Professor James P. Collman working on picket fence porphyrin models for haemoglobin. In 1973 he joined the faculty of the University of Southern California, becoming Professor in 1979. After 25 years at USC, he moved to his present position of Distinguished Professor of Chemistry at UC-Riverside to build the Centre for s and p Block Chemistry. His present research interests focus on weakly coordinating anions, weakly coordinated ligands, acids, si- lylium ion chemistry, cationic catalysis and reactive cations across the periodic table. His earlier work included extensive studies in metalloporphyrin chemistry, models for dioxygen-binding copper proteins, spin-spin coupling phenomena including paramagnetic metal to ligand radical coupling, a Magnetochemi- cal alternative to the Spectrochemical Series, fullerene redox chemistry, fullerene-porphyrin supramolecular chemistry and metal-organic framework solids (MOFs). -

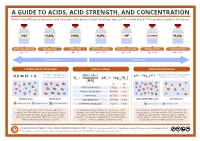

A Guide to Acids, Acid Strength, and Concentration

A GUIDE TO ACIDS, ACID STRENGTH, AND CONCENTRATION What’s the difference between acid strength and concentration? And how does pH fit in with these? This graphic explains the basics. CH COOH HCl H2SO4 HNO3 H3PO4 HF 3 H2CO3 HYDROCHLORIC ACID SULFURIC ACID NITRIC ACID PHOSPHORIC ACID HYDROFLUORIC ACID ETHANOIC ACID CARBONIC ACID pKa = –7 pKa = –2 pKa = –2 pKa = 2.12 pKa = 3.45 pKa = 4.76 pKa = 6.37 STRONGER ACIDS WEAKER ACIDS STRONG ACIDS VS. WEAK ACIDS ACIDS, Ka AND pKa CONCENTRATION AND pH + – The H+ ion is transferred to a + A decrease of one on the pH scale represents + [H+] [A–] pH = –log10[H ] a tenfold increase in H+ concentration. HA H + A water molecule, forming H3O Ka = pKa = –log10[Ka] – [HA] – – + + A + + A– + A + A H + H H H H A H + H H H A Ka pK H – + – H a A H A A – + A– A + H A– H A– VERY STRONG ACID >0.1 <1 A– + H A + + + – H H A H A H H H + A – + – H A– A H A A– –3 FAIRLY STRONG ACID 10 –0.1 1–3 – – + A A + H – – + – H + H A A H A A A H H + A A– + H A– H H WEAK ACID 10–5–10–3 3–5 STRONG ACID WEAK ACID VERY WEAK ACID 10–15–10–5 5–15 CONCENTRATED ACID DILUTE ACID + – H Hydrogen ions A Negative ions H A Acid molecules EXTREMELY WEAK ACID <10–15 >15 H+ Hydrogen ions A– Negative ions Acids react with water when they are added to it, The acid dissociation constant, Ka, is a measure of the Concentration is distinct from strength. -

Acids Lewis Acids and Bases Lewis Acids Lewis Acids: H+ Cu2+ Al3+ Lewis Bases

E5 Lewis Acids and Bases (Session 1) Acids November 5 - 11 Session one Bronsted: Acids are proton donors. • Pre-lab (p.151) due • Problem • 1st hour discussion of E4 • Compounds containing cations other than • Lab (Parts 1and 2A) H+ are acids! Session two DEMO • Lab: Parts 2B, 3 and 4 Problem: Some acids do not contain protons Lewis Acids and Bases Example: Al3+ (aq) = ≈ pH 3! Defines acid/base without using the word proton: + H H H • Cl-H + • O Cl- • • •• O H H Acid Base Base Acid . A BASE DONATES unbonded ELECTRON PAIR/S. An ACID ACCEPTS ELECTRON PAIR/S . Deodorants and acid loving plant foods contain aluminum salts Lewis Acids Lewis Bases . Electron rich species; electron pair donors. Electron deficient species ; potential electron pair acceptors. Lewis acids: H+ Cu2+ Al3+ “I’m deficient!” Ammonia hydroxide ion water__ (ammine) (hydroxo) (aquo) Acid 1 Lewis Acid-Base Reactions Lewis Acid-Base Reactions Example Metal ion + BONDED H H H + • to water H + • O O • • •• molecules H H Metal ion Acid + Base Complex ion surrounded by water . The acid reacts with the base by bonding to one molecules or more available electron pairs on the base. The acid-base bond is coordinate covalent. The product is a complex or complex ion Lewis Acid-Base Reaction Products Lewis Acid-Base Reaction Products Net Reaction Examples Net Reaction Examples 2+ 2+ + + Pb + 4 H2O [Pb(H2O)4] H + H2O [H(H2O)] Lewis acid Lewis base Tetra aquo lead ion Lewis acid Lewis base Hydronium ion 2+ 2+ 2+ 2+ Ni + 6 H2O [Ni(H2O)6] Cu + 4 H2O [Cu(H2O)4] Lewis acid Lewis base Hexa aquo nickel ion Lewis acid Lewis base Tetra aquo copper(II)ion DEMO DEMO Metal Aquo Complex Ions Part 1. -

Superacid Chemistry

SUPERACID CHEMISTRY SECOND EDITION George A. Olah G. K. Surya Prakash Arpad Molnar Jean Sommer SUPERACID CHEMISTRY SUPERACID CHEMISTRY SECOND EDITION George A. Olah G. K. Surya Prakash Arpad Molnar Jean Sommer Copyright # 2009 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permission. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. -

Soaps and Detergents • the Next Time You Are in a Supermarket, Go to the Aisle with Soaps and Detergents

23 Table of Contents 23 Unit 6: Interactions of Matter Chapter 23: Acids, Bases, and Salts 23.1: Acids and Bases 23.2: Strengths of Acids and Bases 23.3: Salts Acids and Bases 23.1 Acids • Although some acids can burn and are dangerous to handle, most acids in foods are safe to eat. • What acids have in common, however, is that they contain at least one hydrogen atom that can be removed when the acid is dissolved in water. Acids and Bases 23.1 Properties of Acids • An acid is a substance that produces hydrogen ions in a water solution. It is the ability to produce these ions that gives acids their characteristic properties. • When an acid dissolves in water, H+ ions + interact with water molecules to form H3O ions, which are called hydronium ions (hi DROH nee um I ahnz). Acids and Bases 23.1 Properties of Acids • Acids have several common properties. • All acids taste sour. • Taste never should be used to test for the presence of acids. • Acids are corrosive. Acids and Bases 23.1 Properties of Acids • Acids also react with indicators to produce predictable changes in color. • An indicator is an organic compound that changes color in acid and base. For example, the indicator litmus paper turns red in acid. Acids and Bases 23.1 Common Acids • At least four acids (sulfuric, phosphoric, nitric, and hydrochloric) play vital roles in industrial applications. • This lists the names and formulas of a few acids, their uses, and some properties. Acids and Bases 23.1 Bases • You don’t consume many bases. -

Introduction to Ionic Mechanisms Part I: Fundamentals of Bronsted-Lowry Acid-Base Chemistry

INTRODUCTION TO IONIC MECHANISMS PART I: FUNDAMENTALS OF BRONSTED-LOWRY ACID-BASE CHEMISTRY HYDROGEN ATOMS AND PROTONS IN ORGANIC MOLECULES - A hydrogen atom that has lost its only electron is sometimes referred to as a proton. That is because once the electron is lost, all that remains is the nucleus, which in the case of hydrogen consists of only one proton. The large majority of organic reactions, or transformations, involve breaking old bonds and forming new ones. If a covalent bond is broken heterolytically, the products are ions. In the following example, the bond between carbon and oxygen in the t-butyl alcohol molecule breaks to yield a carbocation and hydroxide ion. H3C CH3 H3C OH H3C + OH CH3 H3C A tertiary Hydroxide carbocation ion The full-headed curved arrow is being used to indicate the movement of an electron pair. In this case, the two electrons that make up the carbon-oxygen bond move towards the oxygen. The bond breaks, leaving the carbon with a positive charge, and the oxygen with a negative charge. In the absence of other factors, it is the difference in electronegativity between the two atoms that drives the direction of electron movement. When pushing arrows, remember that electrons move towards electronegative atoms, or towards areas of electron deficiency (positive, or partial positive charges). The electron pair moves towards the oxygen because it is the more electronegative of the two atoms. If we examine the outcome of heterolytic bond cleavage between oxygen and hydrogen, we see that, once again, oxygen takes the two electrons because it is the more electronegative atom. -

Lesson 21: Acids & Bases

Lesson 21: Acids & Bases - Far From Basic Lesson Objectives: • Students will identify acids and bases by the Lewis, Bronsted-Lowry, and Arrhenius models. • Students will calculate the pH of given solutions. Getting Curious You’ve probably heard of pH before. Many personal hygiene products make claims about pH that are sometimes based on true science, but frequently are not. pH is the measurement of [H+] ion concentration in any solution. Generally, it can tell us about the acidity or alkaline (basicness) of a solution. Click on the CK-12 PLIX Interactive below for an introduction to acids, bases, and pH, and then answer the questions below. Directions: Log into CK-12 as follows: Username - your Whitmore School Username Password - whitmore2018 Questions: Copy and paste questions 1-3 in the Submit Box at the bottom of this page, and answer the questions before going any further in the lesson: 1. After dragging the small white circles (in this simulation, the indicator papers) onto each substance, what do you observe about the pH of each substance? 2. If you were to taste each substance (highly inadvisable in the chemistry laboratory!), how would you imagine they would taste? 3. Of the three substances, which would you characterize as acid? Which as basic? Which as neutral? Use the observed pH levels to support your hypotheses. Chemistry Time Properties of Acids and Bases Acids and bases are versatile and useful materials in many chemical reactions. Some properties that are common to aqueous solutions of acids and bases are listed in the table below. Acids Bases conduct electricity in solution conduct electricity in solution turn blue litmus paper red turn red litmus paper blue have a sour taste have a slippery feeling react with acids to create a neutral react with bases to create a neutral solution solution react with active metals to produce hydrogen gas Note: Litmus paper is a type of treated paper that changes color based on the acidity of the solution it comes in contact with. -

Title a Hydronium Solvate Ionic Liquid

A Hydronium Solvate Ionic Liquid: Facile Synthesis of Air- Title Stable Ionic Liquid with Strong Bronsted Acidity Kitada, Atsushi; Takeoka, Shun; Kintsu, Kohei; Fukami, Author(s) Kazuhiro; Saimura, Masayuki; Nagata, Takashi; Katahira, Masato; Murase, Kuniaki Journal of the Electrochemical Society (2018), 165(3): H121- Citation H127 Issue Date 2018-02-22 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/240665 © The Author(s) 2018. Published by ECS. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License (CC BY, Right http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted reuse of the work in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Type Journal Article Textversion publisher Kyoto University Journal of The Electrochemical Society, 165 (3) H121-H127 (2018) H121 A Hydronium Solvate Ionic Liquid: Facile Synthesis of Air-Stable Ionic Liquid with Strong Brønsted Acidity Atsushi Kitada, 1,z Shun Takeoka,1 Kohei Kintsu,1 Kazuhiro Fukami,1,∗ Masayuki Saimura,2 Takashi Nagata,2 Masato Katahira,2 and Kuniaki Murase1,∗ 1Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Kyoto University, Yoshida-honmachi, Sakyo, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan 2Institute of Advanced Energy, Gokasho, Uji, Kyoto 611-0011, Japan + A new kind of ionic liquid (IL) with strong Brønsted acidity, i.e., a hydronium (H3O ) solvate ionic liquid, is reported. The IL can + + be described as [H3O · 18C6]Tf2N, where water exists as the H3O ion solvated by 18-crown-6-ether (18C6), of which the counter – – + anion is bis(trifluoromethylsulfonyl)amide (Tf2N ;Tf= CF3SO2). The hydrophobic Tf2N anion makes [H3O · 18C6]Tf2N stable + in air. -

Drugs and Acid Dissociation Constants Ionisation of Drug Molecules Most Drugs Ionise in Aqueous Solution.1 They Are Weak Acids Or Weak Bases

Drugs and acid dissociation constants Ionisation of drug molecules Most drugs ionise in aqueous solution.1 They are weak acids or weak bases. Those that are weak acids ionise in water to give acidic solutions while those that are weak bases ionise to give basic solutions. Drug molecules that are weak acids Drug molecules that are weak bases where, HA = acid (the drug molecule) where, B = base (the drug molecule) H2O = base H2O = acid A− = conjugate base (the drug anion) OH− = conjugate base (the drug anion) + + H3O = conjugate acid BH = conjugate acid Acid dissociation constant, Ka For a drug molecule that is a weak acid The equilibrium constant for this ionisation is given by the equation + − where [H3O ], [A ], [HA] and [H2O] are the concentrations at equilibrium. In a dilute solution the concentration of water is to all intents and purposes constant. So the equation is simplified to: where Ka is the acid dissociation constant for the weak acid + + Also, H3O is often written simply as H and the equation for Ka is usually written as: Values for Ka are extremely small and, therefore, pKa values are given (similar to the reason pH is used rather than [H+]. The relationship between pKa and pH is given by the Henderson–Hasselbalch equation: or This relationship is important when determining pKa values from pH measurements. Base dissociation constant, Kb For a drug molecule that is a weak base: 1 Ionisation of drug molecules. 1 Following the same logic as for deriving Ka, base dissociation constant, Kb, is given by: and Ionisation of water Water ionises very slightly. -

X Amino Acid Ionic Liquids

molecules Article The Proton Dissociation of Bio-Protic Ionic Liquids: [AAE]X Amino Acid Ionic Liquids Ting He 1, Cheng-Bin Hong 2, Peng-Chong Jiao 1, Heng Xiang 1, Yan Zhang 1, Hua-Qiang Cai 1,*, Shuang-Long Wang 2 and Guo-Hong Tao 2,* 1 Institute of Chemical Materials, China Academy of Engineering Physics, Mianyang 621900, China; [email protected] (T.H.); [email protected] (P.-C.J.); [email protected] (H.X.); [email protected] (Y.Z.) 2 College of Chemistry, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610064, China; [email protected] (C.-B.H.); [email protected] (S.-L.W.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (H.-Q.C.); [email protected] (G.-H.T.); Tel.: +86-28-85470368 (G.-H.T.) Abstract: [AAE]X composed of amino acid ester cations is a sort of typically “bio-based” protic ionic liquids (PILs). They possess potential Brønsted acidity due to the active hydrogens on their cations. The Brønsted acidity of [AAE]X PILs in green solvents (water and ethanol) at room temperature was systematically studied. Various frameworks of amino acid ester cations and four anions were investigated in this work from the viewpoint of structure–property relationship. Four different ways were used to study the acidity. Acid dissociation constants (pKa) of [AAE]X determined by the OIM (overlapping indicator method) were from 7.10 to 7.73 in water and from 8.54 to 9.05 in ethanol. The pKa values determined by the PTM (potential titration method) were from 7.12 to 7.82 in water. Their 1 Hammett acidity function (H0) values (0.05 mol L− ) were about 4.6 in water.