A Stroll Through Hesiod's Tartarus

Total Page:16

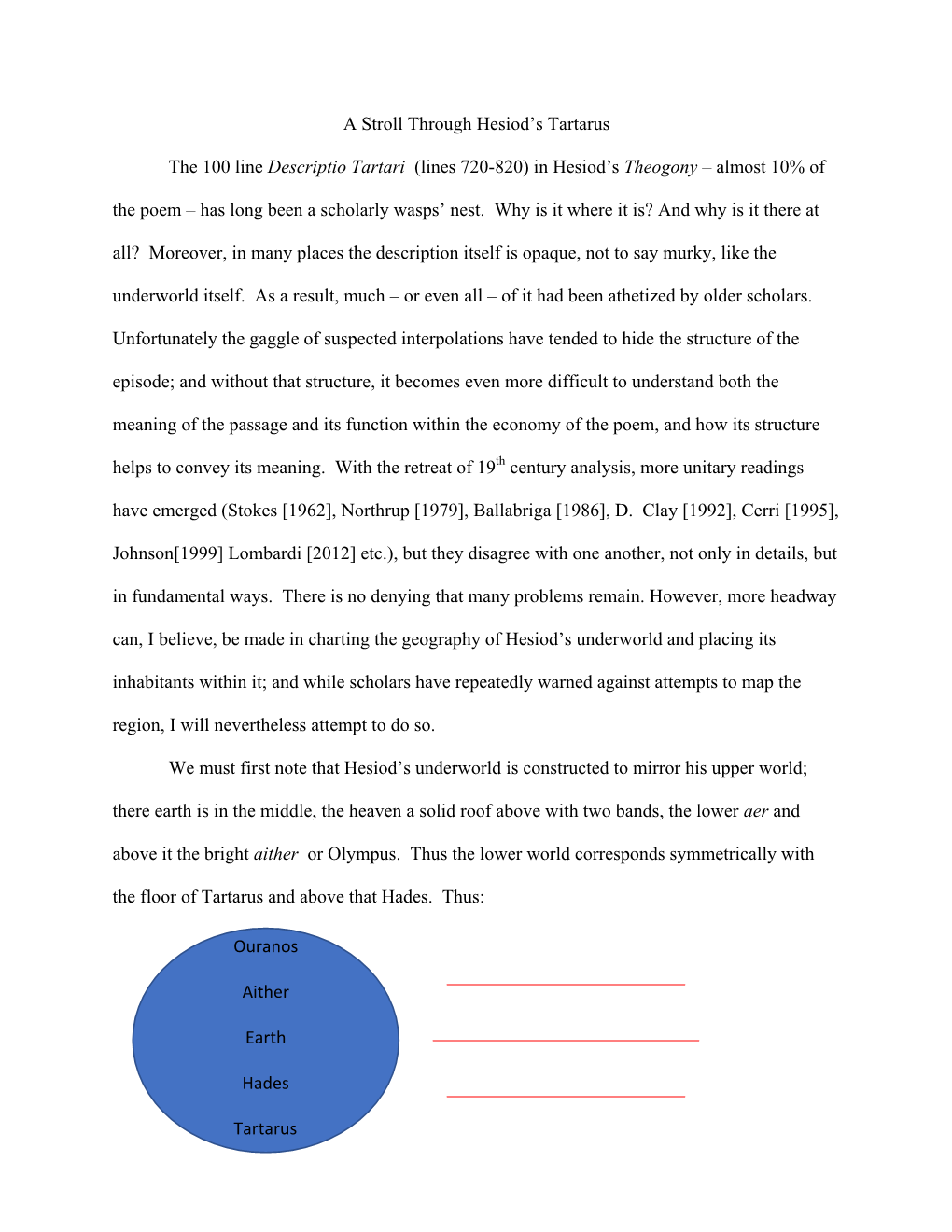

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cosmic Myths of Homer and Hesiod

Oral Tradition, 2/1 (1987): 31-53 The Cosmic Myths of Homer and Hesiod Eric A. Havelock I HOMER’S COSMIC IMAGERY Embedded in the narratives of the Homeric poems are a few passages which open windows on the ways in which the Homeric poet envisioned the cosmos around him. They occur as brief digressions, offering powerful but by no means consistent images, intruding into the narrative and then vanishing from it, but always prompted by some suitable context. A. Iliad 5.748-52 and 768-69 The Greeks in battle being pressed hard by the Trojans, assisted by the god Ares; the goddesses Hera and Athene decide to equalize the encounter by descending from Olympus to help the Greeks. A servant assembles the components of Hera’s chariot: body, wheels, spokes, axle, felloe, tires, naves, platform, rails, pole, yoke are all itemized in sequence, comprising a formulaic account of a mechanical operation: Hera herself attaches the horses to the car. Athene on her side is provided by the poet with a corresponding “arming scene”; she fi nally mounts the chariot and the two of them proceed: 748 Hera swiftly with whip set upon the horses 749 and self-moving the gates of heaven creaked, which the seasons kept 750 to whom is committed great heaven and Olympus 751 either to swing open the thick cloud or to shut it back. 752 Straight through between them they kept the horses goaded-and-driven. 32 ERIC A. HAVELOCK 768 Hera whipped up the horses, and the pair unhesitant fl ew on 769 in midspace between earth and heaven star-studded. -

Tradition and Innovation in Olympiodorus' "Orphic" Creation of Mankind Radcliffe .G Edmonds III Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Greek, Latin, and Classical Studies Faculty Research Greek, Latin, and Classical Studies and Scholarship 2009 A Curious Concoction: Tradition and Innovation in Olympiodorus' "Orphic" Creation of Mankind Radcliffe .G Edmonds III Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/classics_pubs Part of the Classics Commons Custom Citation Edmonds, Radcliffe .,G III. "A Curious Concoction: Tradition and Innovation in Olympiodorus' 'Orphic' Creation of Mankind." American Journal of Philology 130, no. 4 (2009): 511-532. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/classics_pubs/79 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Radcliffe G. Edmonds III “A Curious Concoction: Tradition and Innovation in Olympiodorus' ‘Orphic’ Creation of Mankind” American Journal of Philology 130 (2009), pp. 511–532. A Curious Concoction: Tradition and Innovation in Olympiodorus' Creation of Mankind Olympiodorus' recounting (In Plat. Phaed. I.3-6) of the Titan's dismemberment of Dionysus and the subsequent creation of humankind has served for over a century as the linchpin of the reconstructions of the supposed Orphic doctrine of original sin. From Comparetti's first statement of the idea in his 1879 discussion of the gold tablets from Thurii, Olympiodorus' brief testimony has been the -

ΤΑΡΤΑΡΟΣ in Greco-Roman Culture, Second Temple Judaism, and Philo of Alexandria* Clint Burnett (Boston College)

Going Through Hell; ΤΑΡΤΑΡΟΣ in Greco-Roman Culture, Second Temple Judaism, and Philo of Alexandria* Clint Burnett (Boston College) Tis article questions the longstanding supposition that the eschatology of the Second Temple period was solely infuenced by Persian or Iranian eschatology, arguing instead that the litera- ture of this period refects awareness of several key Greco-Roman mythological concepts. In particular, the concepts of Tartarus and the Greek myths of Titans and Giants underlie much of the treatment of eschatology in the Jewish literature of the period. A thorough treatment of Tartarus and related concepts in literary and non-literary sources from ancient Greek and Greco-Roman culture provides a backdrop for a discussion of these themes in the Second Tem- ple period and especially in the writings of Philo of Alexandria. I. Introduction Contemporary scholarship routinely explores connections between Greco- Roman culture and Second Temple Judaism, but one aspect of this investiga- tion that has not received the attention it deserves is eschatology. Te view that the eschatology of the Second Temple period was shaped largely by Persian es- chatology remains dominant in the feld.1 As James Barr has observed, “Many of the scholars of the ‘biblical theology’ period, were very anxious to make it clear that biblical thought was entirely distinct from, and owed nothing to, Greek thought. … Iranian infuence, however, seemed … less of a threat.”2 Tis is somewhat surprising, given that many Second Temple Jewish texts, including the writings of Philo of Alexandria, mention eschatological con- cepts developed in a Greco-Roman context. Signifcant among these are the many references to the Greco-Roman subterranean prison of Tartarus and the related mythology of the Titans and Giants. -

Child Abuse in Greek Mythology: a Review C Stavrianos, I Stavrianou, P Kafas

The Internet Journal of Forensic Science ISPUB.COM Volume 3 Number 1 Child Abuse in Greek Mythology: A Review C Stavrianos, I Stavrianou, P Kafas Citation C Stavrianos, I Stavrianou, P Kafas. Child Abuse in Greek Mythology: A Review. The Internet Journal of Forensic Science. 2007 Volume 3 Number 1. Abstract The aim of this review was to describe child abuse cases in ancient Greek mythology. Names like Hercules, Saturn, Aesculapius, Medea are very familiar. The stories can be divided into 3 categories: child abuse from gods to gods, from gods to humans and from humans to humans. In these stories children were abused in different ways and the reasons were of social, financial, political, religious, medical and sexual origin. The interpretations of the myths differed and the conclusions seemed controversial. Archaeologists, historians, and philosophers still try to bring these ancient stories into light in connection with the archaeological findings. The possibility for a dentist to face a child abuse case in the dental office nowadays proved the fact that child abuse was not only a phenomenon of the past but also a reality of the present. INTRODUCTION courses are easily available to everyone. Child abuse may be defined as any non-accidental trauma, On 1860 the forensic odontologist Ambroise Tardieu, neglect, failure to meet basic needs or abuse inflicted upon a referring to 32 cases, made a connection between subdural child by a caretaker that is beyond the acceptable norm of haematoma and abuse. In 1874 a church group in New York childcare in our culture. Abused children found in all 1 City took a child named Mary-Helen from home in which economic, social, ethnic and cultural backgrounds and she was being abused. -

Lecture 9 Good Morning and Welcome to LLT121 Classical Mythology

Lecture 9 Good morning and welcome to LLT121 Classical Mythology. In our last exciting class, we were discussing the various sea gods. You’ll recall that, in the beginning, Gaia produced, all by herself, Uranus, the sky, Pontus, the sea and various mountains and whatnot. Pontus is the Greek word for “ocean.” Oceanus is another one. Oceanus is one of the Titans. Guess what his name means in ancient Greek? You got it. It means “ocean.” What we have here is animism, pure and simple. By and by, as Greek civilization develops, they come to think of the sea as ruled by this bearded god, lusty, zesty kind of god. Holds a trident. He’s seriously malformed. He has an arm growing out of his neck this morning. You get the picture. This is none other than the god Poseidon, otherwise known to the Romans as Neptune. One of the things that I’m going to be mentioning as we meet the individual Olympian gods, aside from their Roman names—Molly, do you have a problem with my drawing? Oh, that was the problem. Okay, aside from their Roman names is also their quote/unquote attributes. Here’s what I mean by attributes: recognizable features of a particular god or goddess. When you’re looking at, let’s say, ancient Greek pottery, all gods and goddesses look pretty much alike. All the gods have beards and dark hair. All the goddesses have long, flowing hair and are wearing dresses. The easiest way to tell them apart is by their attributes. -

Myth and Origins: Men Want to Know

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, October 2015, Vol. 5, No. 10, 930-945 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2015.10.013 D DAVID PUBLISHING Myth and Origins: Men Want to Know José Manuel Losada Université Complutense, Madrid, Spain Starting with a personal definition of “myth”, this paper seeks to substantiate the claim that every myth is essentially etiological, in the sense that myths somehow express a cosmogony or an eschatology, whether particular or universal. In order to do that, this study reassesses Classical and Judeo-Christian mythologies to revisit and contrast the narratives of origin—of the cosmos, of the gods and of men—found in ancient polytheism and in Judeo-Christian monotheism. Taking into consideration how these general and particular cosmogonies convey a specific understanding of the passage of time, this article does not merely recount the cosmogonies, theogonies, and anthropogonies found in the Bible and in the works of authors from Classical Antiquity, but it also incorporates a critical commentary on pieces of art and literature that have reinterpreted such mythical tales in more recent times. The result of the research is the disclosure of a sort of universal etiology that may be found in mythology which, as argued, explains the origins of the world, of the gods, and of men so as to satisfy humankind’s ambition to unveil the mysteries of the cosmos. Myth thus functions in these cases as a vehicle that makes it possible for man to return the fullness of a primordial age, abandoning the fleeting time that entraps him and entering a time still absolute. -

Greek God Pantheon.Pdf

Zeus Cronos, father of the gods, who gave his name to time, married his sister Rhea, goddess of earth. Now, Cronos had become king of the gods by killing his father Oranos, the First One, and the dying Oranos had prophesied, saying, “You murder me now, and steal my throne — but one of your own Sons twill dethrone you, for crime begets crime.” So Cronos was very careful. One by one, he swallowed his children as they were born; First, three daughters Hestia, Demeter, and Hera; then two sons — Hades and Poseidon. One by one, he swallowed them all. Rhea was furious. She was determined that he should not eat her next child who she felt sure would he a son. When her time came, she crept down the slope of Olympus to a dark place to have her baby. It was a son, and she named him Zeus. She hung a golden cradle from the branches of an olive tree, and put him to sleep there. Then she went back to the top of the mountain. She took a rock and wrapped it in swaddling clothes and held it to her breast, humming a lullaby. Cronos came snorting and bellowing out of his great bed, snatched the bundle from her, and swallowed it, clothes and all. Rhea stole down the mountainside to the swinging golden cradle, and took her son down into the fields. She gave him to a shepherd family to raise, promising that their sheep would never be eaten by wolves. Here Zeus grew to be a beautiful young boy, and Cronos, his father, knew nothing about him. -

THE COSMOLOGICAL HIERARCHY and APOLLO's TIMAI Implicit in The

APPENDIX 2 THE COSMOLOGICAL HIERARCHY AND APOLLO'S TIMAI Implicit in the Hymn to Apollo is an ontological hierarchy comprising three levels or realms: the divine, the human, and the monstrous or demonic. Each has its proper locus in the physical world. The region assigned to the gods is the superterrestrial, whether "steep Olympus" (109 8£wv t8o~ ocl1tuv "O)..uµ1tov) or "broad heaven" (325 &8ocva'tOLaLV 01. oupocvov £upuv lxouat). Mankind belongs on the "grain-giving soil" itself (69 8vT)'tOfotv ~po'tofow l1tl ~£(8wpov apoupocv), "eating the fruit of the much nourishing earth" (365 yoc(T)~ 1t0Aucp6p~ou xocp1tov laovn~). The subterra nean regions "around great Tartarus" are, if not the proper habitation of monsters like the serpent and Typhon, then at least their point of emana tion into the world of men. Leto's oath to Delos and Hera's prayer for a son, both utterances of great solemnity and power, embrace all three realms at once, Leto swearing by "earth and heaven and the dripping water of Styx" (84-85) and Hera invoking "earth and heaven and the Titan gods who dwell under the earth around great Tartarus" (334-336). In certain respects the divine and the human realms form a common society that stands apart from the monstrous/demonic; thus Delos speaks of the yet-unborn Apollo as destined "to lord it mightily over immortals and mortal men'' (68-69 µlyoc 8! 1tpu't0tv£uatµ£v &8ocva'tOLatv xocl 8vT)'tOtaL ~po'toiaw), the Muses sing of the "immortal gifts of the gods and the suf ferings of men'' ( 190-191 8£wv 8wp' aµ~pO'tOt 1)8' &v8pw1twv 'tAT)(J.Oauvoc~), and the "terrible and grievous Typhon," who "resembles neither gods nor mortals'' (351 oun 8£0I~ lvoc)..(yxtov oun ~po'tofot), is produced by Hera as an enemy both of mankind (306, 352 1tijµoc ~po'tofotv) and of Zeus himself (338-339). -

Gods and Goddesses

GODS AND GODDESSES Greek Roman Description Name Name Adonis God of beauty and desire Goddess of love and beauty, wife of Hephaestus, was said to have been born fully- Aphrodite Venus grown from the sea-foam. Dove God of the poetry, music, sun. God of arts, of light and healing (Roman sun god) Apollo Apollo twin brother of Artemis, son of Zeus. Bow (war), Lyre (peace) Ares Mars Hated god of war, son of Zeus and Hera. Armor and Helmet Goddess of the hunt, twin sister of Apollo, connected with childbirth and the healing Artemis Diana arts. Goddess of the moon. Bow & Arrow Goddess of War & Cunning wisdom, patron goddess of the useful arts, daughter of Athena Minerva Zeus who sprang fully-grown from her father's head. Titan sky god, supreme ruler of the titans and father to many Olympians, his Cronus Saturn reign was referred to as 'the golden age'. Goddess of the harvest, nature, particularly of grain, sister of Zeus, mother of Demeter Ceres Persephone. Sheaves of Grain Dionysus Bacchus God of wine and vegetation, patron god of the drama. Gaia Terra Mother goddess of the earth, daughter of Chaos, mother of Uranus. God of the underworld, ruler of the dead, brother of Zeus, husband of Persephone. Hades Pluto Invisible Helmet Lame god of the forge, talented blacksmith to the gods, son of Zeus and Hera, Hephaestus Vulcan husband of Aphrodite. God of fire and volcanos. Tools, Twisted Foot Goddess of marriage and childbirth, queen of the Olympians, jealous wife and sister Hera Juno of Zeus, mother of Hephaestus, Ares and Hebe. -

The Labours of Heracles

The Fi~t Labour: The Nemean Lion . The First Labour which Eurfstheus imposed on Heracles, when he The Thl~d !;a?our: The Ceryneian Hind .. came to reside at Tiryns, was to kill and flay the Nemean, or Cleonaen H~racles s ~ hlrd Labour was to capture t?e C~rynelan Hmd, and lion, an enormous beast with a pelt proof agail,st iron, bronze, and bring her ahve from Oenoe to Mycenae. This swIft, dappled creature stone. had brazen hooves and golden horns like a stag, so that some call her . Arriving at Cleonae, between Corinth and Argos, Heracles lodged a .stag. She was sacred to Art~mis \vho, when only a child, saw five m the house o~ a day-l~bourer, or shepherd, named Molorchus, hInds, l.arge!than bulls, grazIng on the banks o~ the dark-pebbled whose son the hon had killed. When Molorchus was about to offer a Thessahan nver Anaurus at the foot of the Parrhaslan Mountains; the ram in propitiation of Hera, Heracles restrained him. 'Wait thirty sun twinkled on their horns. Running in pursuit, she caught four of day~: he said. 'If I return safely, sacrifice to Saviour Zeus; if I do not, them, one after the other, with her own hands, and harnessed them sacrifice to me as a hero!' . .. to.her chariot; .the fifth fled across the river Celadon to the Ceryneian Heraclesreache~ Nemea at midday, but SIncethe hon had HiIl- asHera Intended, already having Heracles's Labours in mind. depopulated the nelghbourhoo~, he found no one to direct him; nor Loth either to kill or wound the hind, Heracles performed this were any tracks to be seen. -

The Punishment of Atlas

The Myth of Tantalus (from Wikipedia.org) In mythology, Tantalus became one of the inhabitants of Tartarus, the deepest portion of the Underworld, reserved for the punishment of evildoers; there Odysseus saw him. Tantalus was initially known for having been welcomed to Zeus’ table in Olympus. There he is said to have misbehaved and stolen ambrosia and nectar to bring it back to his people, and revealed the secrets of the gods. Most famously, Tantalus offered up his son, Pelops, as sacrifice. He cut Pelops up, boiled him, and served him up in a banquet for the gods. The gods became aware of the gruesome nature of the menu, so they didn’t touch the offering; only Demeter, distraught by the loss of her daughter, Persephone, absentmindedly ate part of the boy’s shoulder. Clotho, one of the three Fates, ordered by Zeus, brought the boy to life again (she collected the parts of the body and boiled them in a sacred cauldron), rebuilding his shoulder with one wrought of ivory made by Hephaestus and presented by Demeter. The revived Pelops grew to be an extraordinarily handsome youth. The god Poseidon took him to Mount Olympus to teach him to use chariots. Later, Zeus threw Pelops out of Olympus due to his anger at Tantalus. The Greeks of classical times claimed to be horrified by Tantalus’s doings; cannibalism, human sacrifice and infanticide were atrocities and taboo. Tantalus’s punishment for his act, now a proverbial term for temptation without satisfaction (the source of the English word “tantalize”), was to stand in a pool of water beneath a fruit tree with low branches. -

The Theoi “But Let Us Now Go to Bed and Turn to LoveMaking

The Theoi “But let us now go to bed and turn to lovemaking. For never before has love for any goddess or woman so melted about the heart inside me, broken it to submission, as now: not that time when I loved the wife of Ixion who bore me Peirithroös, equal of the gods in counsel, nor when I loved Akrisios’ daughter, sweetstepping Danaë, who bore Perseus to me, preeminent among all men, nor when I loved the daughter of farrenowned Phoinix, Europa who bore Minos to me, and Rhadamanthys the godlike; not when I loved Semele, or Alkmene in Thebe, when Alkmene bore me a son, Herakles the stronghearted, while Semele’s son was Dionysos, the pleasure of mortals; not when I loved the queen Demeter of the lovely tresses, not when it was glorious Leto nor yourself, so much as now I love you, and the sweet passion has taken hold of me.” —Zeus to Hera, The Iliad, Book 14 “Why do I listen to him? Why do I believe him when I know he’s a liar and a cheat? I’ll tell you. It’s because he’s—Hey! Put your brother down this instant, young man! I don’t care what he did, if you drop him off the roof one more time, so help me—” —June Oxnard, incarnation of Hera The World was born of the great chasm, Chaos, from whence arose Gaia, who birthed her equal, Uranus, to enshroud her in the sky. To Uranus, Gaia bore twelve great Titans, the Cyclopes, and the HundredHanded—but Uranus, fearful of his children’s power and hateful of their appearance, confined the Cyclopes and the HundredHanded in Tartarus, far beneath Gaia, which caused her great pain.