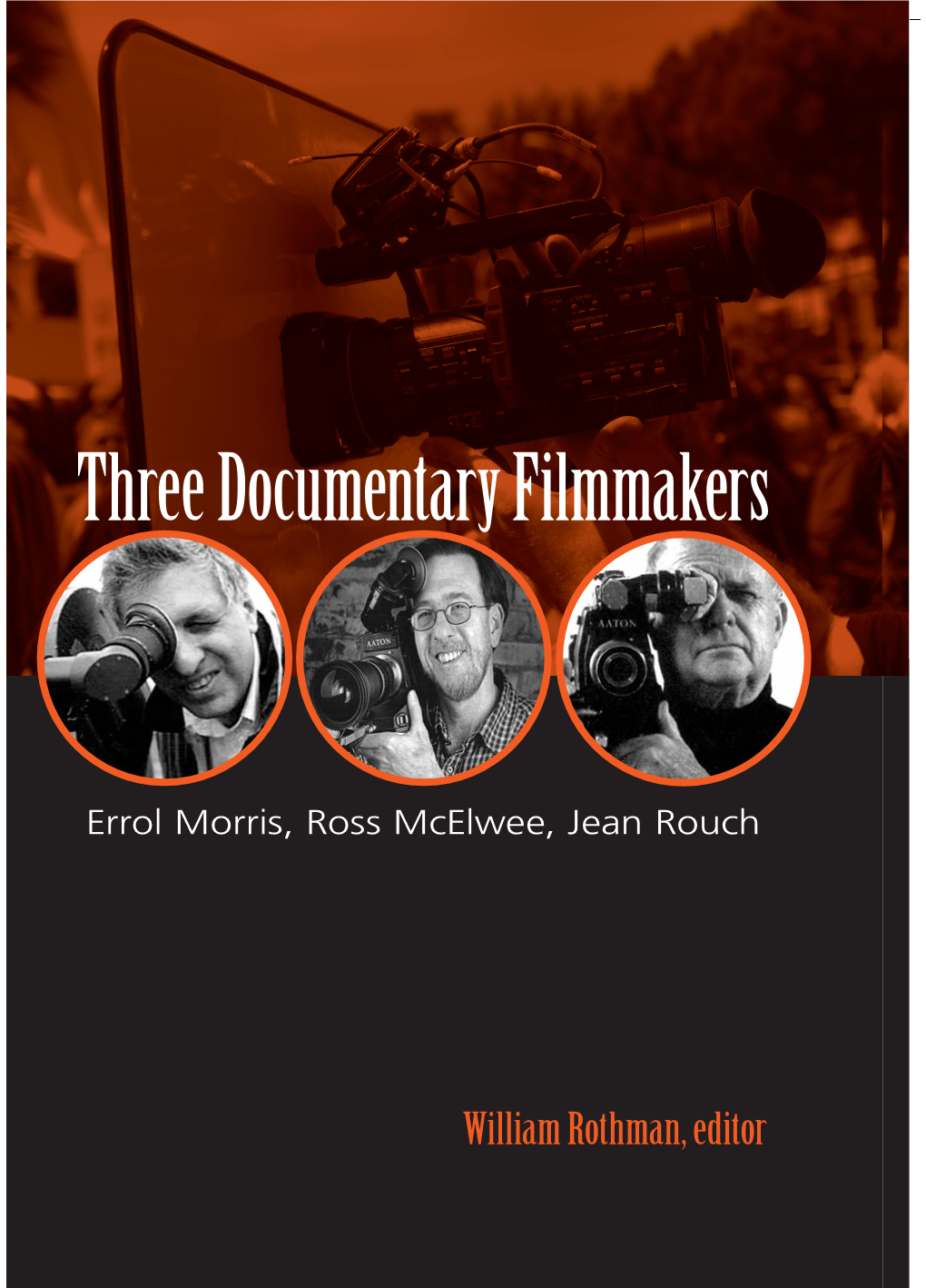

Three Documentary Filmmakers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Representing History and the Filmmaker in the Frame

REPRESENTING HISTORY AND THE FILMMAKER IN THE FRAME Trent Griffiths* Resumo: A presença do realizador no enquadramento representa uma relação única entre o documentário e a História em que o realizador se envolve na história social através da sua experiência pessoal e enquanto autor de uma representação. O realizador no enquadramento é, também, um representante do momento histórico, ao explorar de modo reflexivo o encontro com o processo de mediação e auto-representação que caracteriza a sociedade pós-moderna. Palavras-chave: subjetividade, auto-reflexividade, realizador no enquadramento. Resumen: La presencia del director en el encuadre representa una relación úni- ca entre el documental y la historia, en la cual el director se involucra en la historia social a través de su experiencia personal como autor de una representación. El director en el encuadre es también un representante del momento histórico, al explorar de modo reflexivo el encuentro con el proceso de mediación y auto-representación que caracteriza a la sociedad posmoderna. Palabras clave: subjetividad, auto-reflexividad, director en el encuadre. Abstract: The presence of the filmmaker as a subject in the documentary frame represents a unique relationship between documentary film and history, where the filmmaker engages with social history through their personal experience of authoring a representation of it. This paper explores how the tension between the filmmaker’s presence as an author and as a subject enacts a kind of self-reflexivity that recasts the possibilities of representing history through documentary film. Keywords: Subjectivity, self-reflexivity, filmmaker in the frame. Résumé: La présence du réalisateur dans l’image cinématographique témoigne d’une relation unique entre documentaire et histoire : le réalisateur s’engage dans l’his- toire sociale à travers d’une expérience personnelle et comme auteur d’une représen- tation. -

Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those Listed Are Directors, Unless Otherwise Noted

1 COM 321, Documentary Form in Film & Television 1/15/14 Documentarists and Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers Those listed are directors, unless otherwise noted. Documentary/Narrative Filmmakers—Many have done both: Name & Key Documentaries Key Narrative Works Nation Allen, Woody Zelig, 1983 (mockumentary) Annie Hall, 1977 US Manhattan, 1979 Altman, Robert The James Dean Story, 1957 M*A*S*H, 1970 US The Player, 1992 Short Cuts, 1993 Anderson, Lindsay Thursday’s Children, 1954 (with Guy if. , 1968 Britain Brenton) O Lucky Man!, 1973 Anger, Kenneth Kustom Kar Kommandos, 1963 Fireworks, 1947 US Scorpio Rising, 1964 Apted, Michael The Up! series (1970‐2012 so far) Gorillas in the Mist, 1988 Britain Nell, 1994 The World is Not Enough, 1999 Brakhage, Stan The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Dog Star Man, 1962 US Eyes, 1971 Mothlight, 1963 Bunuel, Luis Las Hurdes (Land Without Bread), Un Chien Andalou, 1928 (with Salvador Spain/France 1933 (mockumentary?) Dali) L’Age D’Or, 1930 The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, 1972 Cameron, James Expedition Bismarck, 2002 Titanic, 1997 US Ghosts of the Abyss, 2003 Avatar, 2009 Capra, Frank Why We Fight series, 1942‐44 Mr. Deeds Goes to Town, 1936 US Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, 1939 It’s a Wonderful Life, 1946 Chukrai, Grigori Pamyat, 1971 Ballad of a Soldier, 1959 Soviet Union Cooper, Merian C. Grass: A Nation’s Battle for Life, 1925 The Four Feathers, 1929 US (with Ernest B. Schoedsack) King Kong, 1933 Chang: A Drama of the Wilderness, 1927 (with Ernest B. Schoedsack) Demme, Jonathan Stop Making Sense, -

2012-Loft-Film-Fest-Program

Festival Parties Join us as we cut the ribbon on our brand-new third screen! Ribbon cutting Friday November 9 at 5:00pm Open House 5:00 - 6:30pm Join the Loft staff, Board of Directors and local officials as we un- veil our new third screen (or what we affectionately call Screen 3)! You’ll be the first to step inside this new space for a behind-the- Loft Film Fest 2012 scenes tour! Join us for a champagne toast as we celebrate a job well done by an incredible team of dedicated people! loftfilmfest.com We will recognize the donors who made this phase of the project Inspired by film’s unique ability to entertain, engage, challenge and possible and we will especially honor those who have given their illuminate, The Loft Cinema will present its third annual international name to key parts of the project, including Bob Oldfather and film festival fromNovember 8th – 15th, 2012. Bookmans for the 3-D technology in Screen 3! Honoring Tucson’s richly diverse cultural community, The Loft Film Fest will present foreign films, documentaries and U.S. indies in a cin- You’re invited to The Loft Cinema’s ematic celebration of storytelling from around the world. 40th birthday party! The Loft Film Fest is an eight-day showcase of exclusive, one-time-only Friday November 15 from 5:30 - 7:30pm screenings and will feature: Yes, we know we don’t look 40, but The Loft is celebrating four • Festival favorites from Cannes, Sundance, Telluride, and more! decades of great film in Tucson! • Lively Q&A’s with talented filmmakers and actors Join us as we honor the last 40 years and toast the next 40! • Exciting retrospective screenings Where: The Lodge on the Desert • New international cinema 306 North Alvernon Way • Edgy Late Night movies When: 5:30 - 7:30pm, Thursday, November 15 (the actual 10th an- • Stimulating shorts from the filmmakers of tomorrow niversary of our purchase of The Loft as a nonprofit in 2002!) At the Loft Film Fest, audiences experience world-class film festival Who: Everyone! Loft Film Fest passholders get in free. -

Landscapes of the Self: the Cinema of Ross Mcelwee Paisajes Del Yo: El Cine De Ross Mcelwee

LANDSCAPES OF THE SELF: THE CINEMA OF ROSS MCELWEE PAISAJES DEL YO: EL CINE DE ROSS MCELWEE EFRÉN CUEVAS ALBERTO N. GARCÍA (eds.) EDICIONES INTERNACIONALES UNIVERSITARIAS MADRID Queda prohibida, salvo excepción prevista en la ley, cualquier forma de reproducción, distribución, comunicación pú bli ca y transformación, total o parcial, de esta obra sin contar con autorización escrita de los titulares del Copy right. La infracción de los derechos mencionados puede ser constitutiva de delito contra la propiedad intelectual (Artículos 270 y ss. del Código Penal). Primera edición: Febrero 2008 © 2007. Efrén Cuevas Álvarez y Alberto N. García Martínez (eds.) Ediciones Internacionales Universitarias, S.A. Pantoja, 14 bajo – 28002 Madrid Teléfono: +34 915 193 907 - Fax: +34 914 136 808 e-mail: [email protected] Diseño cubierta: Irene Cuevas ([email protected]) ISBN: 978-84-8469-226-3 • Depósito legal: NA 2.731-2007 Impreso en España por: Imagraf, S.L.L. Mutilva Baja. (Navarra) TABLE OF CONTENTS ÍNDICE Introduction Introducción .......................................................................................................... 9 Establishing Shot [a profile of the filmmaker] Plano de situación [un perfil del cineasta] Stephen Rodrick The Meaning of Life El sentido de la vida ............................................................................................... 21 Wide Angle [essays on the cinema of Ross McElwee] Gran angular [estudios sobre el cine de Ross McElwee] Efrén Cuevas Sculpting the Self: Autobiography According to -

Three Experiments in Cinéma Vérité by Ross Simonton Mcelwee

Three Experiments in Cinéma Vérité by Ross Simonton McElwee, III A.B., Brown University 1971 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June, 1977 Signature of Author . Department of Architecture, May 19 1977 Certified by . Richard Leacock, Professor of Cinema Thesis Supervisor Accepted by . Nicholas Negroponte, Chairman Departmental Committee for Graduate Students - 1 - The entire work of Jean Renoir is an esthetic of sensuality; not the affirmation of an archaic rule of the senses or of an unrestrained hedonism, but the assurance that all beauty, all wisdom, even all intelligence live only through the testament of the senses. To understand the world is above all to know how to look at it and make it abandon itself to your love under the caress of your eye. André Bazin - 2 - TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract . page 4 I. Introduction. page 6 II. First Films: Filene’s and 68 Albany Street . page 7 III. Charleen . page 13 IV. Backyard . page 34 V. Space Coast . page 44 VI. Technical Appendix . page 56 - 3 - Three Experiments in Cinéma Vérité Ross Simonton McElwee, III submitted to the Department of Architecture on May 19, 1977 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science The two short films I have written about, Filene’s and 68 Albany Street, were shot during the semester I was a special student at the M.I.T. Film Section. The three major films discussed were shot durinq the three semesters I was a candidate for the degree of Master of Science. -

CRITERION COLLECTION PRESENTS the Ballad of Narayama

AVAILABLE on BLU-RAY AnD DVD! THE CRITERION COLLECTION PRESENTS ThE BALLAD of NarayamA THE GORGEOUS JAPANESE CLASSIC— NEVER BEFORE ON BLU-RAY OR DVD! This haunting, kabuki-inflected version of a Japanese folk legend is set in a remote mountain village, where food is scarce and tradition dictates that citizens who have reached their seventieth year must be carried to the summit of Mount Narayama and left there to die. The sacrificial elder at the center of the tale is Orin (Ugetsu’s KINUYO TANAKA), a dignified and dutiful woman who spends her dwindling days securing the happiness of her loyal widowed son with a respectable new wife. Filmed almost entirely on cunningly designed studio sets, in brilliant color and widescreen, The Ballad of Narayama is a stylish and vividly formal work from Japan’s cinematic golden age, directed by the dynamic KEISUKE KINOSHITA (Twenty-four Eyes). “A startling, culturally resonant SPECIAL EDITION FEATURES magnum opus.” · New 4K digital master from the 2011 restoration, —Cannes Film Festival with uncompressed monaural soundtrack on the Blu-ray edition · Trailer and teaser “Unforgettable . One of · New English subtitle translation Kinoshita’s boldest films.” · PLUS: A booklet featuring an essay by critic —Film Society of Lincoln Center Philip Kemp WINNER BLU-RAY EDITION SRP $29.95 Best FILM, Best Director, PREBOOK 1/8/13 STREET 2/5/13 Best Actress, Cat. NO. CC2228BD KINEMA JUNPO Awards, 1958 ISBN 978-1-60465-687-9 UPC 7-15515-10251-3 WINNER Best FILM, Best Director, DVD EDITION SRP $19.95 MAINICHI FILM Concours, 1958 PREBOOK 1/8/13 STREET 2/5/13 Cat. -

The Great Documentaries II Instructor: Michael Fox Mondays, 12 Noon-1:30Pm, June 7-28, 2021 [email protected]

The Great Documentaries II Instructor: Michael Fox Mondays, 12 noon-1:30pm, June 7-28, 2021 [email protected] With nonfiction films entrenched as a genre of mainstream movie entertainment, we examine standouts of the contemporary documentary. The five-session lineup is comprised of a trio of films about recent historical events bookended by personal documentaries. This lecture and discussion class (students will view the films on their own prior to class) encompasses perennial issues such as the responsibility of the filmmaker to his/her subject, the slipperiness of truth, the tools of storytelling and the use of poetry and metaphor in nonfiction. Four of the films can be streamed for free (three on Kanopy, one on Hoopla) and the other can be rented from Amazon Prime and other platforms. All the films are probably available via Netflix’s DVD plan. The Great Documentaries II is a historical survey that follows and builds on Documentary Touchstones I and II, which I taught at OLLI a few years ago. I’ve appended a list of those films and more information at the end of the syllabus, if you have never seen them and wish to journey further back into the history of documentaries. Most of the titles are available to watch for free on YouTube, although the quality of the prints varies. June 7 Sherman’s March (1986, Ross McElwee, 158 min) Kanopy After his girlfriend leaves him, McElwee voyages along the original route followed by Gen. William Sherman. Rather than cutting a swath of destruction designed to force the Confederate South into submission, McElwee searches for love, camera in hand, “training his lens with phallic resolve on every accessible woman he meets.” Grand Jury Prize at Sundance, named one of the Top 20 docs of all time by the International Documentary Association, added to the Library of Congress National Film Registry in 2000. -

Part Two: Synaesthetic Cinema: the End of Drama

PART TWO: SYNAESTHETIC CINEMA: THE END OF DRAMA "The final poem will be the poem of fact in the language of fact. But it will be the poem of fact not realized before." WALLACE STEVENS Expanded cinema has been expanding for a long time. Since it left the underground and became a popular avant-garde form in the late 1950's the new cinema primarily has been an exercise in technique, the gradual development of a truly cinematic language with which to expand further man's communicative powers and thus his aware- ness. If expanded cinema has had anything to say, the message has been the medium.1 Slavko Vorkapich: "Most of the films made so far are examples not of creative use of motion-picture devices and techniques, but of their use as recording instruments only. There are extremely few motion pictures that may be cited as instances of creative use of the medium, and from these only fragments and short passages may be compared to the best achievements in the other arts."2 It has taken more than seventy years for global man to come to terms with the cinematic medium, to liberate it from theatre and literature. We had to wait until our consciousness caught up with our technology. But although the new cinema is the first and only true cinematic language, it still is used as a recording instrument. The recorded subject, however, is not the objective external human con- dition but the filmmaker's consciousness, his perception and its pro- 1 For a comprehensive in-depth history of this development, see: Sheldon Renan, An Introduction to the American Underground Film (New York: Dutton Paperbacks, 1967). -

Scms 2017 Conference Program

SCMS 2017 CONFERENCE PROGRAM FAIRMONT CHICAGO MILLENNIUM PARK March 22–26, 2017 Letter from the President Dear Friends and Colleagues, On behalf of the Board of Directors, the Host and Program Committees, and the Home Office staff, let me welcome everyone to SCMS 2017 in Chicago! Because of its Midwestern location and huge hub airport, not to say its wealth of great restaurants, nightlife, museums, shopping, and architecture, Chicago is always an exciting setting for an SCMS conference. This year at the Fairmont Chicago hotel we are in the heart of the city, close to the Loop, the river, and the Magnificent Mile. You can see the nearby Millennium Park from our hotel and the Art Institute on Michigan Avenue is but a short walk away. Included with the inexpensive hotel rate, moreover, are several amenities that I hope you will enjoy. I know from previewing the program that, as always, it boasts an impressive display of the best, most stimulating work presently being done in our field, which is at once singular in its focus on visual and digital media and yet quite diverse in its scope, intellectual interests and goals, and methodologies. This year we introduced our new policy limiting members to a single role, and I am happy to say that we achieved our goal of having fewer panels overall with no apparent loss of quality in the program or member participation. With this conference we have made presentation abstracts available online on a voluntary basis, and I urge you to let them help you navigate your way through the program. -

Appendix Screenings and Additional Resources

Appendix Screenings and Additional Resources The analyses of various films and television programmes undertaken in this book are intended to function ‘interactively’ with screenings of the films and programmes. To this end, a complete list of works to accompany each chapter is provided below. Certain of these works are available from national and international distribution companies. Specific locations in the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia for each of the listed works are, nevertheless, provided below. The entries include running time and format (16 mm, VHS, or DVD) for each work. (Please note: In certain countries films require copyright clearance for public screening.) Also included below are further or additional screenings of works not analysed or referred to in each chapter. This information is supplemented by suggested further reading. 1 ‘Believe me, I’m of the world’: documentary representation Further reading Corner, J. ‘Civic visions: forms of documentary’ in J. Corner, Television Form and Public Address (London: Edward Arnold, 1995). Corner, J. ‘Television, documentary and the category of the aesthetic’, Screen, 44, 1 (2003) 92–100. Nichols, B. Blurred Boundaries: Questions of Meaning in Contemporary Culture (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994). Renov, M. ‘Toward a poetics of documentary’ in M. Renov (ed.), Theorizing Documentary (New York: Routledge, 1993). 2 Men with movie cameras: Flaherty and Grierson Nanook of the North, Robert Flaherty, 1922. 55 min. (Alternative title: Nanook of the North: A Story -

Karl Heider - Ethnographic Film

ethnographic film TT3867.indb3867.indb i 88/21/06/21/06 112:47:202:47:20 PPMM THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK ethnographic film Revised Edition by karl g. heider university of texas press Austin TT3867.indb3867.indb iiiiii 88/21/06/21/06 112:47:202:47:20 PPMM Copyright © 1976, 2006 by the University of Texas Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Revised edition, 2006 Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to: Permissions University of Texas Press P.O. Box 7819 Austin, TX 78713– 7819 www.utexas.edu/utpress/about/bpermission.html ᭺ϱ The paper used in this book meets the minimum requirements of ansi/niso z39.48 – 1992 (r1997) (Permanence of Paper). library of congress cataloging-in-publication data Heider, Karl G., 1935– Ethnographic fi lm / by Karl G. Heider. — Rev. ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn-13: 978-0-292-71458-8 ((pbk.) : alk. paper) isbn-10: 0-292-71458-o 1. Motion pictures in ethnology. 2. Motion pictures in ethnology–Study and teaching. I. Title. gn347.h44 2006 305.8 –dc22 2006019479 TT3867.indb3867.indb iivv 88/21/06/21/06 112:47:212:47:21 PPMM To Robert Gardner And to the memory of Jean Rouch John Marshall Timothy Asch TT3867.indb3867.indb v 88/21/06/21/06 112:47:222:47:22 PPMM THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK contents preface ix acknowledgments xv 1. introduction 1 Toward a Definition: The Nature of the Category “Ethnographic Film” 1 The Nature of Ethnography 4 The Differing Natures of Ethnography and Film 8 “Truth” in Film and Ethnography 10 2. -

Elondocs Docfilmmaker DVD

Contents Introduction to Documentary Film What is Documentary? (2:37) Why Documentary Matters (4:55) Why they make films (3:45) A Student of Film (2:37) Story Finding Good Stories (4:18) Finding Good People (2:14) Story into film (3:25) First Person Perspective (3:12) Shooting & Editing Sound & Picture (8:32) Editing (5:18) Screening your rough cut (1:08) Legal Issues Releases & Clearances (3:28) Fair Use (1:52) Music (2:38) Ethics General Ethics (4:21) Specific Ethics (7:30) Financial & Distribution Getting Your Film Made (7:30) Getting Your Film Out There (4:06) Documentary Filmmaking: Tips from the Trenches Every year I attend the Full Frame documentary film festival in Durham, North Carolina, bringing a group of students from Elon University. Without fail, we return from the Festival energized by the films and inspired by the expert advice from filmmakers. So I started thinking about ways to recreate that energy in the class- room, eventually arriving at the concept for this DVD. This DVD is a chance to hear from emerging and seasoned filmmakers as they discuss technical, legal, ethical and busi- ness issues of documentary film. It was created to be watched in brief topical sections, although it can also be watched straight through. We’ve organized the subjects as they might be encoun- tered in creating a film, from finding good stories to getting your film out there. This booklet also contains short discussion ques- tions to be used in class or by aspiring filmmakers to think more about the ideas and insights offered by our interviewees.