“This Is Exactly Why We Sweep Things Under the Rug:” a Polite Approach to ABC's Modern Family Presented to the Faculty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

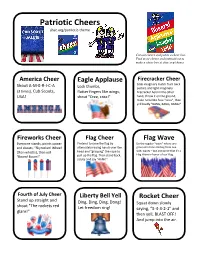

Patriotic Cheers Shac.Org/Patriotic-Theme

Patriotic Cheers shac.org/patriotic-theme Cut out cheers and put in a cheer box. Find more cheers and instructions to make a cheer box at shac.org/cheers. America Cheer Eagle Applause Firecracker Cheer Shout A-M-E-R-I-C-A Grab imaginary match from back Lock thumbs, pocket, and light imaginary (3 times), Cub Scouts, flutter fingers like wings, firecracker held in the other USA! shout "Cree, cree!" hand, throw it on the ground, make noise like fuse "sssss", then yell loudly "BANG, BANG, BANG!" Fireworks Cheer Flag Cheer Flag Wave Everyone stands, points upward Pretend to raise the flag by Do the regular “wave” where one and shouts, “Skyrocket! Whee!” alternately raising hands over the group at a time starting from one (then whistle), then yell head and “grasping” the rope to side, waves – but announce that it’s a Flag Wave in honor of our Flag. “Boom! Boom!” pull up the flag. Then stand back, salute and say “Ahhh!” Fourth of July Cheer Liberty Bell Yell Rocket Cheer Stand up straight and Ding, Ding, Ding, Dong! Squat down slowly shout "The rockets red Let freedom ring! saying, “5-4-3-2-1” and glare!" then yell, BLAST OFF! And jump into the air. Patriotic Cheer Mount New Citizen Cheer To recognize the hard work of Shout “U.S.A!” and thrust hand learning in order to pass the test with doubled up fist skyward Rushmore Cheer to become a new citizen, have while shouting “Hooray for the Washington, Jefferson, everyone stand, make a salute, Red, White and Blue!” Lincoln, Roosevelt! and say “We salute you!” Soldier Cheer Statue of Liberty USA-BSA Cheer Stand at attention and Cheer One group yells, “USA!” The salute. -

Feminism, Postfeminism, Liz Lemonism: Comedy and Gender Politics on 30 Rock

Genders 1998-2013 Genders 1998-2013 Genders 1998-2013 Home (/gendersarchive1998-2013/) Feminism, Postfeminism, Liz Lemonism: Comedy and Gender Politics on 30 Rock Feminism, Postfeminism, Liz Lemonism: Comedy and Gender Politics on 30 Rock May 1, 2012 • By Linda Mizejewski (/gendersarchive1998-2013/linda-mizejewski) [1] The title of Tina Fey's humorous 2011 memoir, Bossypants, suggests how closely Fey is identified with her Emmy-award winning NBC sitcom 30 Rock (2006-), where she is the "boss"—the show's creator, star, head writer, and executive producer. Fey's reputation as a feminist—indeed, as Hollywood's Token Feminist, as some journalists have wryly pointed out—heavily inflects the character she plays, the "bossy" Liz Lemon, whose idealistic feminism is a mainstay of her characterization and of the show's comedy. Fey's comedy has always focused on gender, beginning with her work on Saturday Night Live (SNL) where she became that show's first female head writer in 1999. A year later she moved from behind the scenes to appear in the "Weekend Update" sketches, attracting national attention as a gifted comic with a penchant for zeroing in on women's issues. Fey's connection to feminist politics escalated when she returned to SNL for guest appearances during the presidential campaign of 2008, first in a sketch protesting the sexist media treatment of Hillary Clinton, and more forcefully, in her stunning imitations of vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin, which launched Fey into national politics and prominence. [2] On 30 Rock, Liz Lemon is the head writer of an NBC comedy much likeSNL, and she is identified as a "third wave feminist" on the pilot episode. -

Popular Television Programs & Series

Middletown (Documentaries continued) Television Programs Thrall Library Seasons & Series Cosmos Presents… Digital Nation 24 Earth: The Biography 30 Rock The Elegant Universe Alias Fahrenheit 9/11 All Creatures Great and Small Fast Food Nation All in the Family Popular Food, Inc. Ally McBeal Fractals - Hunting the Hidden The Andy Griffith Show Dimension Angel Frank Lloyd Wright Anne of Green Gables From Jesus to Christ Arrested Development and Galapagos Art:21 TV In Search of Myths and Heroes Astro Boy In the Shadow of the Moon The Avengers Documentary An Inconvenient Truth Ballykissangel The Incredible Journey of the Batman Butterflies Battlestar Galactica Programs Jazz Baywatch Jerusalem: Center of the World Becker Journey of Man Ben 10, Alien Force Journey to the Edge of the Universe The Beverly Hillbillies & Series The Last Waltz Beverly Hills 90210 Lewis and Clark Bewitched You can use this list to locate Life The Big Bang Theory and reserve videos owned Life Beyond Earth Big Love either by Thrall or other March of the Penguins Black Adder libraries in the Ramapo Mark Twain The Bob Newhart Show Catskill Library System. The Masks of God Boston Legal The National Parks: America's The Brady Bunch Please note: Not all films can Best Idea Breaking Bad be reserved. Nature's Most Amazing Events Brothers and Sisters New York Buffy the Vampire Slayer For help on locating or Oceans Burn Notice reserving videos, please Planet Earth CSI speak with one of our Religulous Caprica librarians at Reference. The Secret Castle Sicko Charmed Space Station Cheers Documentaries Step into Liquid Chuck Stephen Hawking's Universe The Closer Alexander Hamilton The Story of India Columbo Ansel Adams Story of Painting The Cosby Show Apollo 13 Super Size Me Cougar Town Art 21 Susan B. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom

30 Rock: Complexity, Metareferentiality and the Contemporary Quality Sitcom Katrin Horn When the sitcom 30 Rock first aired in 2006 on NBC, the odds were against a renewal for a second season. Not only was it pitched against another new show with the same “behind the scenes”-idea, namely the drama series Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip. 30 Rock’s often absurd storylines, obscure references, quick- witted dialogues, and fast-paced punch lines furthermore did not make for easy consumption, and thus the show failed to attract a sizeable amount of viewers. While Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip did not become an instant success either, it still did comparatively well in the Nielson ratings and had the additional advantage of being a drama series produced by a household name, Aaron Sorkin1 of The West Wing (NBC, 1999-2006) fame, at a time when high-quality prime-time drama shows were dominating fan and critical debates about TV. Still, in a rather surprising programming decision NBC cancelled the drama series, renewed the comedy instead and later incorporated 30 Rock into its Thursday night line-up2 called “Comedy Night Done Right.”3 Here the show has been aired between other single-camera-comedy shows which, like 30 Rock, 1 | Aaron Sorkin has aEntwurf short cameo in “Plan B” (S5E18), in which he meets Liz Lemon as they both apply for the same writing job: Liz: Do I know you? Aaron: You know my work. Walk with me. I’m Aaron Sorkin. The West Wing, A Few Good Men, The Social Network. -

Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Pell Scholars and Senior Theses Salve's Dissertations and Theses 5-2010 Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions Stephanie Savage Salve Regina University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses Part of the Advertising and Promotion Management Commons, and the Marketing Commons Savage, Stephanie, "Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions" (2010). Pell Scholars and Senior Theses. 54. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses/54 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Salve's Dissertations and Theses at Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pell Scholars and Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Savage 1 “Who’s gonna turn down a Junior Mint? It’s chocolate, it’s peppermint ─it’s delicious!” While this may sound like your typical television commercial, you can thank Jerry Seinfeld and his butter fingers for what is actually one of the most renowned lines in television history. As part of a 1993 episode of Seinfeld , subsequently known as “The Junior Mint,” these infamous words have certainly gained a bit more attention than the show’s writers had originally bargained for. In fact, those of you who were annoyed by last year’s focus on a McDonald’s McFlurry on NBC’s 30 Rock may want to take up your beef with Seinfeld’s producers for supposedly showing marketers the way to the future ("Brand Practice: Product Integration Is as Old as Hollywood Itself"). -

Blacks Reveal TV Loyalty

Page 1 1 of 1 DOCUMENT Advertising Age November 18, 1991 Blacks reveal TV loyalty SECTION: MEDIA; Media Works; Tracking Shares; Pg. 28 LENGTH: 537 words While overall ratings for the Big 3 networks continue to decline, a BBDO Worldwide analysis of data from Nielsen Media Research shows that blacks in the U.S. are watching network TV in record numbers. "Television Viewing Among Blacks" shows that TV viewing within black households is 48% higher than all other households. In 1990, black households viewed an average 69.8 hours of TV a week. Non-black households watched an average 47.1 hours. The three highest-rated prime-time series among black audiences are "A Different World," "The Cosby Show" and "Fresh Prince of Bel Air," Nielsen said. All are on NBC and all feature blacks. "Advertisers and marketers are mainly concerned with age and income, and not race," said Doug Alligood, VP-special markets at BBDO, New York. "Advertisers and marketers target shows that have a broader appeal and can generate a large viewing audience." Mr. Alligood said this can have significant implications for general-market advertisers that also need to reach blacks. "If you are running a general ad campaign, you will underdeliver black consumers," he said. "If you can offset that delivery with those shows that they watch heavily, you will get a small composition vs. the overall audience." Hit shows -- such as ABC's "Roseanne" and CBS' "Murphy Brown" and "Designing Women" -- had lower ratings with black audiences than with the general population because "there is very little recognition that blacks exist" in those shows. -

73Rd-Nominations-Facts-V2.Pdf

FACTS & FIGURES FOR 2021 NOMINATIONS as of July 13 does not includes producer nominations 73rd EMMY AWARDS updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page 1 of 20 SUMMARY OF MULTIPLE EMMY WINS IN 2020 Watchman - 11 Schitt’s Creek - 9 Succession - 7 The Mandalorian - 7 RuPaul’s Drag Race - 6 Saturday Night Live - 6 Last Week Tonight With John Oliver - 4 The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel - 4 Apollo 11 - 3 Cheer - 3 Dave Chappelle: Sticks & Stones - 3 Euphoria - 3 Genndy Tartakovsky’s Primal - 3 #FreeRayshawn - 2 Hollywood - 2 Live In Front Of A Studio Audience: “All In The Family” And “Good Times” - 2 The Cave - 2 The Crown - 2 The Oscars - 2 PARTIAL LIST OF 2020 WINNERS PROGRAMS: Comedy Series: Schitt’s Creek Drama Series: Succession Limited Series: Watchman Television Movie: Bad Education Reality-Competition Program: RuPaul’s Drag Race Variety Series (Talk): Last Week Tonight With John Oliver Variety Series (Sketch): Saturday Night Live PERFORMERS: Comedy Series: Lead Actress: Catherine O’Hara (Schitt’s Creek) Lead Actor: Eugene Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actress: Annie Murphy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actor: Daniel Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Drama Series: Lead Actress: Zendaya (Euphoria) Lead Actor: Jeremy Strong (Succession) Supporting Actress: Julia Garner (Ozark) Supporting Actor: Billy Crudup (The Morning Show) Limited Series/Movie: Lead Actress: Regina King (Watchman) Lead Actor: Mark Ruffalo (I Know This Much Is True) Supporting Actress: Uzo Aduba (Mrs. America) Supporting Actor: Yahya Abdul-Mateen II (Watchmen) updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page -

17 Essential Social Skills Every Child Needs to Make & Retain Friends

Thriving Series by MICHAEL GROSE 17 essential social skills every child needs to make & retain friends www.parentingideas.com.au 17 essential social skills every child needs to make and retain friends Contents Skill 1: Ability to share possessions and space 4 Skill 2: Keeping confidences and secrets 4 Skill 3: Offering to help 5 Skill 4: Accepting other’s mistakes 5 Skill 5: Being positive and enthusiastic 6 Skill 6: Holding a conversation 6 Skill 7: Winning and losing well 7 Skill 8: Listening to others 7 Skill 9: Ignoring someone who is annoying you 8 Skill 10: Giving and receiving compliments 8 Skill 11: Approaching and joining a group 9 Skill 12: Leading rather than bossing 9 Skill 13: Arguing well – seeing other’s opinions 10 Skill 14: Bringing others into the group 10 Skill 15: Saying No – resisting peer pressure 11 Skill 16: Dealing with fights and disagreements 11 Skill 17: Being a good host 12 Get a ready-to-go At Home parenting program now at www.parentingideas.com.au 2 17 essential social skills every child needs to make and retain friends First a few thoughts Popularity should not be confused with sociability. A number of studies in recent decades have shown that appearance, personality type and ability impact on a child’s popularity at school. Good-looking, easy-going, talented kids usually win peer popularity polls but that doesn’t necessarily guarantee they will have friends. Those children and young people who develop strong friendships have a definite set of skills that help make them easy to like, easy to relate to and easy to play with. -

General Cheers

NWA Kickball Cheers General Cheers Alamo: Kick it high. Kick it low. Kick it to the Alamo. Alamo, here we come. __________ is number one! Hot Dog: __________ wants a hot dog. __________ wants a coke. __________ wants a Home Run, and that's no joke! __________ wants a an orange. __________ wants a shake. __________ wants a to make it to Home Plate! Rock You [ Stomp, stomp, clap. Stomp, stomp, clap. ] We will, we will … Rock you down. Shake you up. Like a volcano ready to erupt. Watch out world. Here we come. __________ is number one! Froggy There was a little froggy -- sitting on a log He rooted for the other team -- it made no sense at all. We pushed him the water, and bonked his little head. And when he came back up again, this is what he said, he said: Go! Go, go! Go, mighty __________ . Fight! Fight, fight! Fight, mighty __________ . Win! Win, win! Win, mighty __________ . Go! Fight! WIn! Beat 'em till the end. Wooo! Big We’re BIG - B. I. G. And we’re BAD - B. A. D. And we’re BOSS - B. O. S. S. - B. O. S. S. - BOSS ! (REPEAT) We Are We are the __________ . Couldn't be prouder. If you can't hear us, we'll yell a little louder. (REPEAT - Louder each time) Stand Up Two bits! Four bits! Six bits! A dollar! All for the __________ stand up and holler! Call & Answer Cheers Dynamite: Our team is WHAT? DYNAMITE! Our team is WHAT? DYNAMITE! Our team is -- Hold on. -

Man Arrested in Joint Operation

FOOD Queso dip so good you might just cry with happiness C4 SERVING SOUTH CAROLINA SINCE OCTOBER 15, 1894894 WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 5, 2018 $1.00.00 Man arrested in joint operation Manning suspect sought in 3-county crime iff’s Office, grand Monday after a deputy with iff’s Office were able to arrest larceny over Clarendon County Sheriff’s Smith, whom authorities con- spree charged with attempted murder $10,000 by Man- Office received information sidered armed and dangerous, ning Police De- that placed Smith in that area. without incident and recover BY SHARRON HALEY began on Aug. 24, according partment and at- Law enforcement officers a vehicle that Smith had re- Special to The Sumter Item to Clarendon County Sheriff’s tempted armed with Clarendon County Sher- portedly stolen on Aug. 24. Office. SMITH robbery and at- iff’s Office and Manning Po- “There was outstanding co- MANNING — A 27-year-old Lamont Michael-Bryant tempted murder lice Department along with operation of multiple agencies Manning man was arrested Smith has been charged with by West Columbia assistance from the State Law working together that led to a Monday after leading authori- breach of trust/obtaining Police Department. Enforcement Division, North quick and peaceful resolution ties across a three-county goods under false pretenses Smith was arrested in the Charleston Police Department area on a crime spree that by Clarendon County Sher- North Charleston area on and Charleston County Sher- SEE ARREST, PAGE A8 Volunteers clean veterans’ gravesites during Decorate the Decorated event ‘I serve for my family. -

Canadian Canada $7 Spring 2020 Vol.22, No.2 Screenwriter Film | Television | Radio | Digital Media

CANADIAN CANADA $7 SPRING 2020 VOL.22, NO.2 SCREENWRITER FILM | TELEVISION | RADIO | DIGITAL MEDIA The Law & Order Issue The Detectives: True Crime Canadian-Style Peter Mitchell on Murdoch’s 200th ep Floyd Kane Delves into class, race & gender in legal PM40011669 drama Diggstown Help Producers Find and Hire You Update your Member Directory profile. It’s easy. Login at www.wgc.ca to get started. Questions? Contact Terry Mark ([email protected]) Member Directory Ad.indd 1 3/6/19 11:25 AM CANADIAN SCREENWRITER The journal of the Writers Guild of Canada Vol. 22 No. 2 Spring 2020 Contents ISSN 1481-6253 Publication Mail Agreement Number 400-11669 Cover Publisher Maureen Parker Diggstown Raises Kane To New Heights 6 Editor Tom Villemaire [email protected] Creator and showrunner Floyd Kane tackles the intersection of class, race, gender and the Canadian legal system as the Director of Communications groundbreaking CBC drama heads into its second season Lana Castleman By Li Robbins Editorial Advisory Board Michael Amo Michael MacLennan Features Susin Nielsen The Detectives: True Crime Canadian-Style 12 Simon Racioppa Rachel Langer With a solid background investigating and writing about true President Dennis Heaton (Pacific) crime, showrunner Petro Duszara and his team tell us why this Councillors series is resonating with viewers and lawmakers alike. Michael Amo (Atlantic) By Matthew Hays Marsha Greene (Central) Alex Levine (Central) Anne-Marie Perrotta (Quebec) Murdoch Mysteries’ Major Milestone 16 Lienne Sawatsky (Central) Andrew Wreggitt (Western) Showrunner Peter Mitchell reflects on the successful marriage Design Studio Ours of writing and crew that has made Murdoch Mysteries an international hit, fuelling 200+ eps.