The Changing Sociology of Karachi: Causes, Trends and Repercussions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

S# BRANCH CODE BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS 1 24 Abbottabad

BRANCH S# BRANCH NAME CITY ADDRESS CODE 1 24 Abbottabad Abbottabad Mansera Road Abbottabad 2 312 Sarwar Mall Abbottabad Sarwar Mall, Mansehra Road Abbottabad 3 345 Jinnahabad Abbottabad PMA Link Road, Jinnahabad Abbottabad 4 131 Kamra Attock Cantonment Board Mini Plaza G. T. Road Kamra. 5 197 Attock City Branch Attock Ahmad Plaza Opposite Railway Park Pleader Lane Attock City 6 25 Bahawalpur Bahawalpur 1 - Noor Mahal Road Bahawalpur 7 261 Bahawalpur Cantt Bahawalpur Al-Mohafiz Shopping Complex, Pelican Road, Opposite CMH, Bahawalpur Cantt 8 251 Bhakkar Bhakkar Al-Qaim Plaza, Chisti Chowk, Jhang Road, Bhakkar 9 161 D.G Khan Dera Ghazi Khan Jampur Road Dera Ghazi Khan 10 69 D.I.Khan Dera Ismail Khan Kaif Gulbahar Building A. Q. Khan. Chowk Circular Road D. I. Khan 11 9 Faisalabad Main Faisalabad Mezan Executive Tower 4 Liaqat Road Faisalabad 12 50 Peoples Colony Faisalabad Peoples Colony Faisalabad 13 142 Satyana Road Faisalabad 585-I Block B People's Colony #1 Satayana Road Faisalabad 14 244 Susan Road Faisalabad Plot # 291, East Susan Road, Faisalabad 15 241 Ghari Habibullah Ghari Habibullah Kashmir Road, Ghari Habibullah, Tehsil Balakot, District Mansehra 16 12 G.T. Road Gujranwala Opposite General Bus Stand G.T. Road Gujranwala 17 172 Gujranwala Cantt Gujranwala Kent Plaza Quide-e-Azam Avenue Gujranwala Cantt. 18 123 Kharian Gujrat Raza Building Main G.T. Road Kharian 19 125 Haripur Haripur G. T. Road Shahrah-e-Hazara Haripur 20 344 Hassan abdal Hassan Abdal Near Lari Adda, Hassanabdal, District Attock 21 216 Hattar Hattar -

Health, Education and Literacy Programme Annual Report

Health, Education and Literacy Programme Annual Report 2016-2017 Contents Mission Executive Committee Management General Body Members Sub committees Chairperson’s Message About HELP Our Donors Accountability and Transparency Monitoring, Evaluation and Reporting Our Projects Our Friends Financials / Audit Report Our Mission “Through needs assessment to design and implement replicable models of health promotion, health delivery and education for women and children” Executive Committee (Honorary) Prof. Dure Samin Akram Chairperson Associate Prof. S.K Kausar Vice President Prof. Dr. Fehmina Arif General Secretary Dr. Gulrukh Nency Joint Secretary Associate Prof. Dr. Neel Kanth Treasurer Members Ms. Mona Sheikh. Mr. Fareed Khan Ms. Hilda Saeed Ms. Rabia Agha Ms. Reema Jaffery Management Senior Program Manager Dr. Yasmeen Suleman Program Manager Dr. Amara Shakeel General Body members Dr. Fazila Zamindar Dr. Jaleel Siddiqui Dr. Sabin Adil Dr. Qadir Pathan Dr. Shakir Mustafa Ms. Shala Usmani Ms. Erum Ghazi Dr. Imtiaz Mandan Annual Report 2017 Sub committees Audit Committee Mr. Farid Khan Prof. Dr. Fehmina Arif Dr. Yasmeen Suleman Fund Raising Committee Ms. Reema Jaffery Dr. Fazila Zamindar Dr. Amara Shakeel Ms. Mona Shaikh Ms. Rabia Agha Research Committee Prof. Dure Samin Akram Associate Prof. Dr. Neel Kanth Associate Prof. S.K Kausar Prof. Dr. Fehmina Arif Purchasing and Procurement committee Prof. Fehmina Arif Dr. Yasmeen Suleman Associate Prof. Neel Kanth Editorial Board Dr. Yasmeen Suleman Ms. Hilda Saeed Annual Report 2017 Chairperson’s Message HELP has been blessed with many friends, well-wishers and philanthropic assistance. In return, we continue to push towards our Mission “to help those who help themselves”. This translates to empowering people in communities towards improving their living environment and standards of living. -

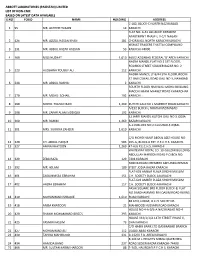

Abbott Laboratories (Pakistan) Limited List of Non-Cnic Based on Latest Data Available S.No Folio Name Holding Address 1 95

ABBOTT LABORATORIES (PAKISTAN) LIMITED LIST OF NON-CNIC BASED ON LATEST DATA AVAILABLE S.NO FOLIO NAME HOLDING ADDRESS C-182, BLOCK-C NORTH NAZIMABAD 1 95 MR. AKHTER HUSAIN 14 KARACHI FLAT NO. A-31 ALLIANCE PARADISE APARTMENT PHASE-I, II-C/1 NAGAN 2 126 MR. AZIZUL HASAN KHAN 181 CHORANGI, NORTH KARACHI KARACHI. KISMAT TRADERS THATTAI COMPOUND 3 131 MR. ABDUL RAZAK HASSAN 53 KARACHI-74000. 4 169 MISS NUZHAT 1,610 469/2 AZIZABAD FEDERAL 'B' AREA KARACHI NAZRA MANZIL FLAT NO 2 1ST FLOOR, RODRICK STREET SOLDIER BAZAR NO. 2 5 223 HUSSAINA YOUSUF ALI 112 KARACHI NADIM MANZIL LY 8/44 5TH FLOOR, ROOM 37 HAJI ESMAIL ROAD GALI NO 3, NAYABAD 6 244 MR. ABDUL RASHID 2 KARACHI FOURTH FLOOR HAJI WALI MOHD BUILDING MACCHI MIANI MARKET ROAD KHARADHAR 7 270 MR. MOHD. SOHAIL 192 KARACHI 8 290 MOHD. YOUSUF BARI 1,269 KUTCHI GALI NO 1 MARRIOT ROAD KARACHI A/192 BLOCK-L NORTH NAZIMABAD 9 298 MR. ZAFAR ALAM SIDDIQUI 192 KARACHI 32 JAFRI MANZIL KUTCHI GALI NO 3 JODIA 10 300 MR. RAHIM 1,269 BAZAR KARACHI A-113 BLOCK NO 2 GULSHAD-E-IQBAL 11 301 MRS. SURRIYA ZAHEER 1,610 KARACHI C/O MOHD HANIF ABDUL AZIZ HOUSE NO. 12 320 CH. ABDUL HAQUE 583 265-G, BLOCK-6 EXT. P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI. 13 327 AMNA KHATOON 1,269 47-A/6 P.E.C.H.S. KARACHI WHITEWAY ROYAL CO. 10-GULZAR BUILDING ABDULLAH HAROON ROAD P.O.BOX NO. 14 329 ZEBA RAZA 129 7494 KARACHI NO8 MARIAM CHEMBER AKHUNDA REMAN 15 392 MR. -

Who Is a Muslim?

4 / Martyr/Mujāhid: Muslim Origins and the Modern Urdu Novel There are two ways to continue the story of the making of a modern lit- er a ture in Urdu a fter the reformist moment of the late nineteenth c entury. The better- known way is to celebrate a rupture from the reformists by writing a history of the All- India Progressive Writer’s Movement (AIPWA), a Bloomsbury- inspired collective that had a tremendous impact on the course of Urdu prose writing. And to be fair, if any single moment DISTRIBUTION— in the modern history of Urdu “lit er a ture” has been able to claim a global circulation (however limited) or express worldly aspirations, it is the well- known moment of the Progressives from within which the stark, rebel voices of Saadat Hasan Manto and Faiz Ahmad Faiz emerged. Founded in 1935–6, the AIPWA was best known for its near revolutionary goals: FOR the desire to create a “new lit er a ture,” which stood directly against the “poetical fancies,” religious orthodoxies, and “love romances with which our periodicals are flooded.”1 Despite its claim to represent all of India, AIPWA was led by a number of Urdu writers— Sajjad Zaheer, Ahmad Ali, among them— who continued, even in the years following Partition in 1947, to have a “disproportionate influence” on the workings and agenda —NOT of the movement.2 The historical and aesthetic successes of the movement, particularly with re spect to Urdu, have gained significant attention from a variety of scholars, including Carlo Coppola, Neetu Khanna, Aamir Mufti, and Geeta Patel, though admittedly more work remains to be done. -

Journal of English Language Teaching and Applied Linguistics ISSN: 2707-756X Website

Journal of English Language Teaching and Applied Linguistics ISSN: 2707-756X Website: www.jeltal.org Original Research Article Culture Shock: Experiences of Balochi Speakers Living in Karachi Nayab Iqbal1and Kaukab Abid Azhar2 * 12Lecturer, Department of Business Administration, Barrett Hodgson University, Karachi, Pakistan Corresponding Author: Kaukab Abid Azhar, E-mail: [email protected] ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History The study aims at finding out instances of culture shock among the Balochi Received: March 02, 2020 speakers at the University of Karachi through conducting semi-structured Accepted: March 30, 2020 interviews with 12 Balochi speakers. The research study is based upon Volume: 2 ‘Qualitative Research Paradigm’ as it is exploratory in nature; therefore it helps to Issue: 1 gain better insights into the subject. Causes of culture shock, phases of culture shock and the strategies adopted by the participants to overcome the challenge of culture shock are the focus of the study. The result reveals language problem, KEYWORDS unhelpful nature of the local people, relationship with elders, independence enjoyed by girls, relationship between gender, co-education, lack of segregation Culture Shock, Acculturation, between male and female in social gatherings, relationship between teachers and Baloch, Balochi Speakers and students and differences in the way of teaching to be the major cause of culture Language Problems shock for the people belonging to the Balochistan Province. Learning Urdu and English language, maintaining group solidarity and mixing up with local people are some of the strategies used by the participants to overcome the problem of culture shock. Besides, the study reveals that participants have passed through the different phases of culture shock while adjusting themselves to the culture in Karachi. -

Accessing Services in the City the Significance of Urban Refugee-Host Relations in Cameroon, Indonesia and Pakistan

ACCESSING SERVICES IN THE CITY THE SIGNIFICANCE OF URBAN REFUGEE-HOST RELATIONS IN CAMEROON, INDONESIA AND PAKISTAN CHURCH WORLD SERVICE FEBRUARY 2013 Graeme Rodgers/CWS ACCESSING SERVICES IN THE CITY THE SIGNIFICANCE OF URBAN REFUGEE-HOST RELATIONS IN CAMEROON, INDONESIA AND PAKISTAN Church World Service, New York Immigration and Refugee Program February 2013 Executive Summary This report considers how relationships between urban refugees and more established local communities affect refugee access to key services and resources. According to the estimates of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the majority of the world’s refugees now reside in cities or towns. In contrast to camps, where refugees are relatively isolated from local host communities and more dependent on assistance from humanitarian agencies to meet their basic needs, refugees in urban areas typically depend more on social networks, relationships and individual agency to re-establish their livelihoods. This study explores the conditions under which refugee-host relations may either promote or inhibit refugee access to local services and other resources. It also considers how positive impacts of these evolving relationships may be nurtured and developed to improve humanitarian outcomes for refugees. In 2009, UNHCR updated its policy on refugees in urban areas, highlighting the challenges of providing protection and assistance in spatially and socially complex environments. This initiative has encouraged the broader humanitarian community to explore more innovative approaches to understanding and programming related to refugees in urban areas. One of the effects of this development has been to highlight the role of the host community and the importance of considering their needs and perspectives. -

Preserving Distinctive Identity Through Cultural Revival: an Analysis of Sindhi Nationalist Movement During One-Unit Era Introdu

Citation: Khan, S. M., Shaheen, M., & Hashmi, M. J. (2021). Preserving Distinctive Identity through Cultural Revival: An Analysis of Sindhi Nationalist Movement during One-Unit Era. Global Political Review, VI(I), 24-36. https://doi.org/10.31703/gpr.2021(VI- I).03 Sultan Mubariz Khan * | Misbah Shaheen† | Muhammad Jawad Hashmi ‡ Preserving Distinctive Identity through Cultural Revival: An Analysis of Sindhi Nationalist Movement during One-Unit Era Vol. VI, No. I (Winter 2021) URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.31703/gpr.2021(VI-I).03 Pages: 24 – 36 p- ISSN: 2521-2982 e- ISSN: 2707-4587 p- ISSN: 2521-2982 DOI: 10.31703/gpr.2021(VI-I).03 Headings Abstract The paper intends to address the fundamental question that whether the movement for cultural revival in • Introduction Sindh during the One-Unit period was a surrogate effort for the • Theoretical Considerations achievement of political goals or it was an effort by the Sindhi intelligentsia to protect Sindhi culture against the government’s patronized onslaught of • Socio-Political Context foreign cultures and to ensure the survival of cultural personality of • Culture Preservation or indigenous Sindhis. The abolishment of Sindh’s provincial status in 1955 to create a unified province of West Pakistan, also called as One-Unit, had Political Autonomy triggered a campaign in Sindh to regain the provincial status. The political • Findings of the Study environment was not permissible for any overt political agitation, so a vigorous campaign for cultural revival spearheaded by the intelligentsia and • Conclusions educated youth emerged with vigor. The study focuses on investigating the • References goals and objectives of the movement by qualitative analysis of data and concludes that the movement endeavoured to protect and strengthen the distinctive cultural personality of indigenous Sindhis within Pakistan Key Words: Sindh, Culture, Ethnic, Identity, Indigenous/Native Sindhi’s Introduction The merger of multiple ethnic communities into phenomenon in such circumstances (Loury 1999). -

List of Branches Authorized for Overnight Clearing (Annexure - II) Branch Sr

List of Branches Authorized for Overnight Clearing (Annexure - II) Branch Sr. # Branch Name City Name Branch Address Code Show Room No. 1, Business & Finance Centre, Plot No. 7/3, Sheet No. S.R. 1, Serai 1 0001 Karachi Main Branch Karachi Quarters, I.I. Chundrigar Road, Karachi 2 0002 Jodia Bazar Karachi Karachi Jodia Bazar, Waqar Centre, Rambharti Street, Karachi 3 0003 Zaibunnisa Street Karachi Karachi Zaibunnisa Street, Near Singer Show Room, Karachi 4 0004 Saddar Karachi Karachi Near English Boot House, Main Zaib un Nisa Street, Saddar, Karachi 5 0005 S.I.T.E. Karachi Karachi Shop No. 48-50, SITE Area, Karachi 6 0006 Timber Market Karachi Karachi Timber Market, Siddique Wahab Road, Old Haji Camp, Karachi 7 0007 New Challi Karachi Karachi Rehmani Chamber, New Challi, Altaf Hussain Road, Karachi 8 0008 Plaza Quarters Karachi Karachi 1-Rehman Court, Greigh Street, Plaza Quarters, Karachi 9 0009 New Naham Road Karachi Karachi B.R. 641, New Naham Road, Karachi 10 0010 Pakistan Chowk Karachi Karachi Pakistan Chowk, Dr. Ziauddin Ahmed Road, Karachi 11 0011 Mithadar Karachi Karachi Sarafa Bazar, Mithadar, Karachi Shop No. G-3, Ground Floor, Plot No. RB-3/1-CIII-A-18, Shiveram Bhatia Building, 12 0013 Burns Road Karachi Karachi Opposite Fresco Chowk, Rambagh Quarters, Karachi 13 0014 Tariq Road Karachi Karachi 124-P, Block-2, P.E.C.H.S. Tariq Road, Karachi 14 0015 North Napier Road Karachi Karachi 34-C, Kassam Chamber's, North Napier Road, Karachi 15 0016 Eid Gah Karachi Karachi Eid Gah, Opp. Khaliq Dina Hall, M.A. -

Sindh Is One of the Ancient Regions of the World. It Now Forms Integral Part of Pakistan. ―Sindh Or Indus Valley Proper Is

Grassroots Vol.50, No.II July-December 2016 A GLIMPSE IN TO THE CONDITIONS OF SINDH BEFORE ARAB CONQUEST Farzana Solangi Muhammad Ali Laghari Nasrullah Kabooro ABSTRACT Ancient history of Sindh dates back to Bronze age civilization, popularly known as Indus valley civilization, which speaks of glorious past of Sindh. Sindh was a vast country before the invasion of Arabs. King was the administrative head in the political setup of the country. Next in power to the king was the minister who exercised great influence over the monarch. King was also the commander of his army. Though king acted as the supreme judge of the country, yet he followed systematic manner in dispensing the justice. The society was divided into two broad classes. The sophisticated upper class consisted of ruling rich and their poets and priests. The lower class consisting of peasants, weavers, tanners, carpenter smiths and itinerant trades men. Family system was patriarchal; women enjoyed a high position in patriarchal society who had liberty to choose their mate. Sindh was a prosperous and fertile country, with flourishing trade. Sindh was abode of various religious groups and sects before the advent of Arabs. On the eve of Arab conquest of Sindh there was rivalry between Hinduism & Buddhism. People of Sindh being unsatisfied by the rule of Brahmans came into contact with Arab invaders and helped them to succeed Brahmans. ____________________ Keywords: Sindh, History, Religions and Social Conditions. INTRODUCTION Sindh is one of the ancient regions of the world. It now forms integral part of Pakistan. ―Sindh or Indus valley proper is a land of great antiquity and claims a civilization anterior in time to that of Egypt and Babylon‖ (Pathan, 1978:46). -

Chapter 4 Environmental Management Consultants Ref: Y8LGOEIAPD ESIA of LNG Terminal, Jetty & Extraction Facility - Pakistan Gasport Limited

ESIA of LNG Terminal, Jetty & Extraction Facility - Pakistan Gasport Limited 4 ENVIRONMENTAL BASELINE OF THE AREA Baseline data being presented here pertain to the data collected from various studies along the physical, biological and socio-economic environment coast show the influence of NE and SW monsoon of the area where the proposed LNG Jetty and land winds. A general summary of meteorological and based terminal will be located, constructed and hydrological data is presented in following operated. Proposed location of project lies within the section to describe the coastal hydrodynamics of boundaries of Port Qasim Authority and very near the area under study. the Korangi Fish Harbour. Information available from electronic/printed literature relevant to A- Temperature & Humidity baseline of the area, surrounding creek system, Port Qasim as well as for Karachi was collected at the The air temperature of Karachi region is outset and reviewed subsequently. This was invariably moderate due to presence of sea. followed by surveys conducted by experts to Climate data generated by the meteorological investigate and describe the existing socio-economic station at Karachi Air Port represents climatic status, and physical scenario comprising conditions for the region. The temperature hydrological, geographical, geological, ecological records for five years (2001-2005) of Karachi city and other ambient environmental conditions of the are being presented to describe the weather area. In order to assess impacts on air quality, conditions. Table 4.1 shows the maximum ambient air quality monitoring was conducted temperatures recorded during the last 5 years in through expertise provided by SUPARCO. The Karachi. baseline being presented in this section is the extract of literature review, analyses of various samples, Summer is usually hot and humid with some surveys and monitoring. -

KARACHI WATER DEMAND & SUPPLY SITUATION MAP Arabian

KARACHI WATER DEMAND & SUPPLY SITUATION MAP Legend as of April 13, 2015 !( Pumping Station !( Water Company Punjab Water Filter Plant Balochistan !( !( Water Supplier Canal JJ AA MM SS HH OO RR OO Lake/River/Dam Sindh Mangrove Total Water Demand (MGD) 803,069,166 803,069,166 - 1,003,855,250 1,003,855,250 - 1,352,817,150 KK AA RR AA CC HH II 1,352,817,150 - 1,924,622,700 LL AA SS BB EE LL AA 1,924,622,700 - 4,912,599,850 Total Current Water (MGD) GADAP TOWN Water Filtration 86,938,428 Water Pumping !( Plant,sewerage !( Station, Colony hub Dam Rd 86,938,428 - 133,498,500 NEW KARACHI 133,498,500 - 223,363,680 25°0'0"N TOWN 25°0'0"N Aquafina, 223,363,680 - 343,165,596 !( karachi, ORANGI hyderabad Road 343,165,596 - 609,361,740 TOWN N.NAZIMABAD MALIR TOWN CANTONMENT GULSHAN E Creation Date: April 17, 2015 Water Pump, IQBAL TOWN Projection/Datum: WGS 84 Geographic !( federal Page Size: ¯ A3 BALDIA B Area Kwsb Water Drizzling TOWN !( Pumping !( GULBERG !( Mineral Water 0 3 6 12 Station !( Suppliers TOWN KM 0 LIAQATABAD Kda Water Plant, FAISAL MALIR SITE !( gulshan-e-iqbal !( TOWN CANTONMENT Pipri Filter 30 TOWN Town !( 330 JAMSHED Plant, Culligan Water darsano Chano TOWN Water Filtration KIAMARI !( Supply,kutchi SHAH !( Plant,pns TOWN LYARI Memon Society FAISAL Mehran 60 TOWN!( TOWN 300 !( BIN QASIM KARACHI CANTONMENT TOWN MANORA LANDHI 270 90 KORANGI CANTONMENT Akhter Colony TOWN +92.51.282.0449/835.9288|[email protected] !(Pure !( Water Pumping TOWN All Rights Reserved - Copyright 2015 !( Water, Station Pumping www.alhasan.com punjab Colony !( Station, korangi Data Source(s): Aqua Sheer,complete!( SADDAR TOWN!( Water Solutions,suit No Karachi Water & Sewerage Board G-104, Marina Elevation DISCLAIMER: Arabian sea ALL RIGHTS RESERVED !( Karachi Water Supply System This product is the sole property of ALHASAN SYSTEMS [www.alhasan.com] - A Knowledge Management, Business CLIFTON Psychology Modeling, and Publishing Company. -

DEMAND for DISTRIBUTED RENEWABLE ENERGY GENERATION in PAKISTAN Main Report

Public Disclosure Authorized DEMAND FOR DISTRIBUTED RENEWABLE ENERGY GENERATION IN PAKISTAN Main Report June 2016 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized This report was prepared by Elan Partners (Pvt.) Ltd, under contract to The World Bank. It is one of several Strategy to Scale- [P146251], which was implemented over the period January 2015 to June 2016. The activity was funded and supported by the Asia Sustainable and Alternative Energy Program (ASTAE), a multi-donor trust fund administered by The World Bank, and was led by Oliver Knight (Senior Energy Specialist) and Anjum Ahmad (Senior Energy Specialist). This report provides an assessment of the potential for distributed renewable energy generation, particularly through solar for large public buildings, major hospitals, major universities, water supply and sewerage pumps, agricultural pumps and agro processing units in selected areas of Pakistan. The work involved data collection, detailed site visits in the selected study areas, and desk-based analysis. The World Bank wishes to thank those organizations that generously provided their time, data and assistance to the consultant team, including representatives from K-Electric, Islamabad Electricity Supply Company (IESCO), and Lahore Electricity Supply Company (LESCO). This report is accompanied by a detailed set of annexes, which can be found here. Copyright © 2016 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / THE WORLD BANK Washington DC 20433 Telephone: +1-202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org This work is a product of the consultants listed, and not of World Bank staff. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent.