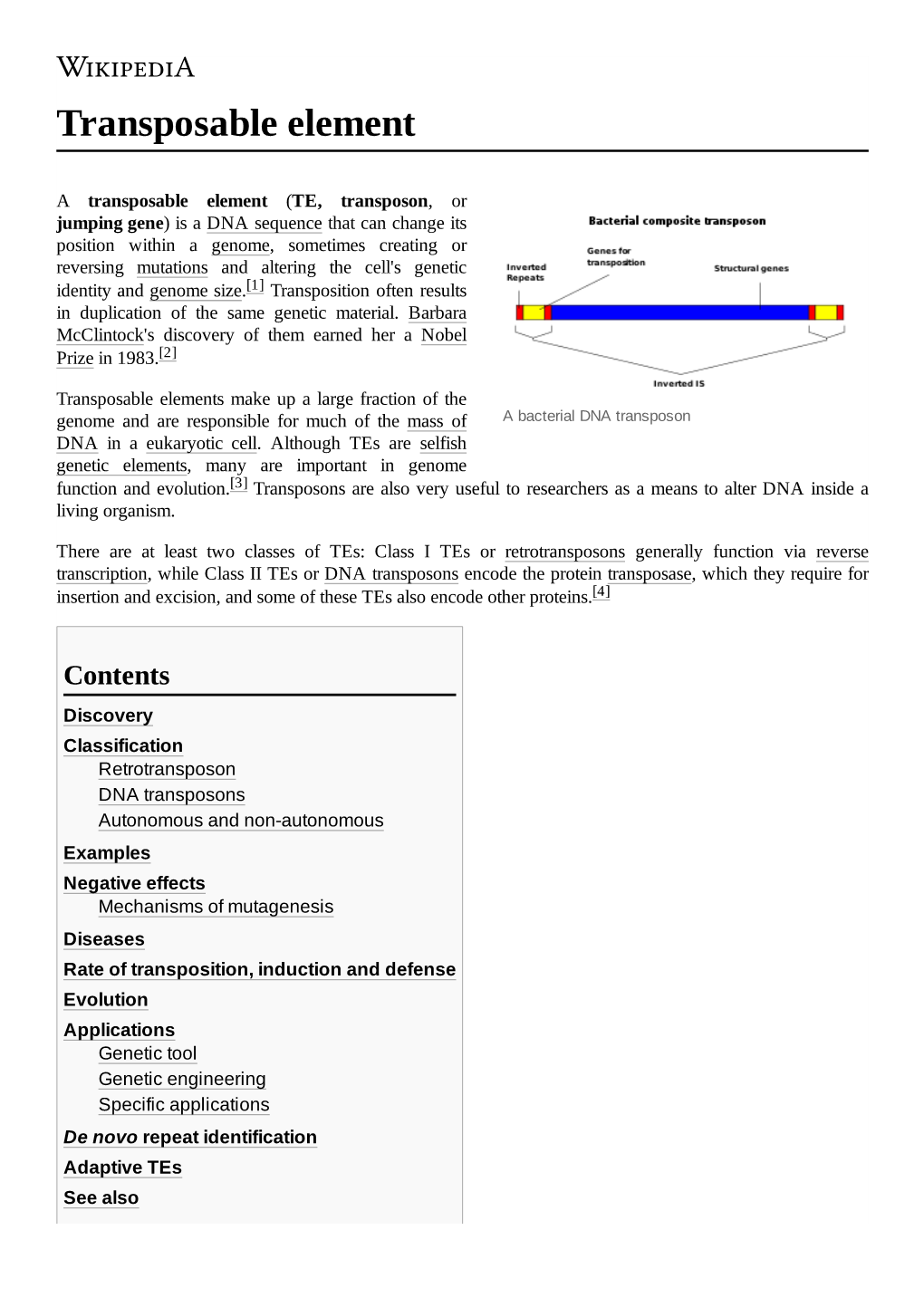

Transposable Element

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mechanisms and Impact of Post-Transcriptional Exon Shuffling

Mechanisms and impact of Post-Transcriptional Exon Shuffling (PTES) Ginikachukwu Osagie Izuogu Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Genetic Medicine Newcastle University September 2016 i ABSTRACT Most eukaryotic genes undergo splicing to remove introns and join exons sequentially to produce protein-coding or non-coding transcripts. Post-transcriptional Exon Shuffling (PTES) describes a new class of RNA molecules, characterized by exon order different from the underlying genomic context. PTES can result in linear and circular RNA (circRNA) molecules and enhance the complexity of transcriptomes. Prior to my studies, I developed PTESFinder, a computational tool for PTES identification from high-throughput RNAseq data. As various sources of artefacts (including pseudogenes, template-switching and others) can confound PTES identification, I first assessed the effectiveness of filters within PTESFinder devised to systematically exclude artefacts. When compared to 4 published methods, PTESFinder achieves the highest specificity (~0.99) and comparable sensitivity (~0.85). To define sub-cellular distribution of PTES, I performed in silico analyses of data from various cellular compartments and revealed diverse populations of PTES in nuclei and enrichment in cytosol of various cell lines. Identification of PTES from chromatin-associated RNAseq data and an assessment of co-transcriptional splicing, established that PTES may occur during transcription. To assess if PTES contribute to the proteome, I analyzed sucrose-gradient fractionated data from HEK293, treated with arsenite to induce translational arrest and dislodge ribosomes. My results showed no effect of arsenite treatment on ribosome occupancy within PTES transcripts, indicating that these transcripts are not generally bound by polysomes and do not contribute to the proteome. -

"Evolutionary Emergence of Genes Through Retrotransposition"

Evolutionary Emergence of Advanced article Genes Through Article Contents . Introduction Retrotransposition . Gene Alteration Following Retrotransposon Insertion . Retrotransposon Recruitment by Host Genome . Retrotransposon-mediated Gene Duplication Richard Cordaux, University of Poitiers, Poitiers, France . Conclusion Mark A Batzer, Department of Biological Sciences, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, doi: 10.1002/9780470015902.a0020783 Louisiana, USA Variation in the number of genes among species indicates that new genes are continuously generated over evolutionary times. Evidence is accumulating that transposable elements, including retrotransposons (which account for about 90% of all transposable elements inserted in primate genomes), are potent mediators of new gene origination. Retrotransposons have fostered genetic innovation during human and primate evolution through: (i) alteration of structure and/or expression of pre-existing genes following their insertion, (ii) recruitment (or domestication) of their coding sequence by the host genome and (iii) their ability to mediate gene duplication via ectopic recombination, sequence transduction and gene retrotransposition. Introduction genes, respectively, and de novo origination from previ- ously noncoding genomic sequence. Genome sequencing Variation in the number of genes among species indicates projects have also highlighted that new gene structures can that new genes are continuously generated over evolution- arise as a result of the activity of transposable elements ary times. Although the emergence of new genes and (TEs), which are mobile genetic units or ‘jumping genes’ functions is of central importance to the evolution of that have been bombarding the genomes of most species species, studies on the formation of genetic innovations during evolution. For example, there are over three million have only recently become possible. -

Cerevls Ae RNA14 Suggests That Melanogaster by Suppressor Of

Downloaded from genesdev.cshlp.org on September 25, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Homology with Saccharomyces cerevls ae RNA14 suggests that phenotypic suppression in Drosophila melanogaster by suppressor of f. o.rked occurs at the level of RNA stabd ty Andrew Mitchelson, Martine Simonelig, 1 Carol Williams, and Kevin O'Hare 2 Department of Biochemistry, Imperial College of Science Technology and Medicine, London SW7 2AZ, UK The suppressor of forked [su(f)] locus of Drosophila melanogaster encodes at least one cell-autonomous vital function. Mutations at su(f) can affect the expression of unlinked genes where retroviral-like transposable elements are inserted. Changes in phenotype are correlated with changes in mRNA profiles, indicating that su(f) affects the production and/or stability of mRNAs. We have cloned the su(f) gene by P-element transposon tagging. Alterations in the DNA map of eight lethal alleles were detected in a 4.3-kb region. P-element- mediated transformation using a fragment including this interval rescued all aspects of the su(f) mutant phenotype. The gene is transcribed to produce a major 2.6-kb RNA and minor RNAs of 1.3 and 2.9 kb, which are present throughout development, being most abundant in embryos, pupae, and adult females. The major predicted gene product is an 84- kD protein that is homologous to RNA14 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a vital gene where mutation affects mRNA stability. This suggests that phenotypic modification by su(f) occurs at the level of RNA stability. [Key Words: Drosophila; modifier gene; transposable element; suppression] Received October 12, 1992; accepted November 23, 1992. -

Transposon Insertion Mutagenesis in Mice for Modeling Human Cancers: Critical Insights Gained and New Opportunities

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Transposon Insertion Mutagenesis in Mice for Modeling Human Cancers: Critical Insights Gained and New Opportunities Pauline J. Beckmann 1 and David A. Largaespada 1,2,3,4,* 1 Department of Pediatrics, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA; [email protected] 2 Masonic Cancer Center, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA 3 Department of Genetics, Cell Biology and Development, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA 4 Center for Genome Engineering, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN 55455, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-612-626-4979; Fax: +1-612-624-3869 Received: 3 January 2020; Accepted: 3 February 2020; Published: 10 February 2020 Abstract: Transposon mutagenesis has been used to model many types of human cancer in mice, leading to the discovery of novel cancer genes and insights into the mechanism of tumorigenesis. For this review, we identified over twenty types of human cancer that have been modeled in the mouse using Sleeping Beauty and piggyBac transposon insertion mutagenesis. We examine several specific biological insights that have been gained and describe opportunities for continued research. Specifically, we review studies with a focus on understanding metastasis, therapy resistance, and tumor cell of origin. Additionally, we propose further uses of transposon-based models to identify rarely mutated driver genes across many cancers, understand additional mechanisms of drug resistance and metastasis, and define personalized therapies for cancer patients with obesity as a comorbidity. Keywords: animal modeling; cancer; transposon screen 1. Transposon Basics Until the mid of 1900’s, DNA was widely considered to be a highly stable, orderly macromolecule neatly organized into chromosomes. -

Ac/Ds-Transposon Activation Tagging in Poplar: a Powerful Tool for Gene Discovery Fladung and Polak

Ac/Ds-transposon activation tagging in poplar: a powerful tool for gene discovery Fladung and Polak Fladung and Polak BMC Genomics 2012, 13:61 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/13/61 (6 February 2012) Fladung and Polak BMC Genomics 2012, 13:61 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/13/61 RESEARCHARTICLE Open Access Ac/Ds-transposon activation tagging in poplar: a powerful tool for gene discovery Matthias Fladung* and Olaf Polak Abstract Background: Rapid improvements in the development of new sequencing technologies have led to the availability of genome sequences of more than 300 organisms today. Thanks to bioinformatic analyses, prediction of gene models and protein-coding transcripts has become feasible. Various reverse and forward genetics strategies have been followed to determine the functions of these gene models and regulatory sequences. Using T-DNA or transposons as tags, significant progress has been made by using “Knock-in” approaches ("gain-of- function” or “activation tagging”) in different plant species but not in perennial plants species, e.g. long-lived trees. Here, large scale gene tagging resources are still lacking. Results: We describe the first application of an inducible transposon-based activation tagging system for a perennial plant species, as example a poplar hybrid (P. tremula L. × P. tremuloides Michx.). Four activation-tagged populations comprising a total of 12,083 individuals derived from 23 independent “Activation Tagging Ds” (ATDs) transgenic lines were produced and phenotyped. To date, 29 putative variants have been isolated and new ATDs genomic positions were successfully determined for 24 of those. Sequences obtained were blasted against the publicly available genome sequence of P. -

The Endogenous Transposable Element Tgm9 Is Suitable for Generating Knockout Mutants for Functional Analyses of Soybean Genes and Genetic Improvement in Soybean

RESEARCH ARTICLE The endogenous transposable element Tgm9 is suitable for generating knockout mutants for functional analyses of soybean genes and genetic improvement in soybean Devinder Sandhu1*, Jayadri Ghosh2, Callie Johnson3, Jordan Baumbach2, Eric Baumert3, Tyler Cina3, David Grant2,4, Reid G. Palmer2,4², Madan K. Bhattacharyya2* a1111111111 1 USDA-ARS, US Salinity Laboratory, Riverside, CA, United States of America, 2 Department of Agronomy, a1111111111 Iowa State University, Ames, IA, United States of America, 3 Department of Biology, University of Wisconsin- a1111111111 Stevens Point, Stevens Point, WI, United States of America, 4 USDA-ARS Corn Insects and Crop Genomics a1111111111 Research Unit, Ames, IA, United States of America a1111111111 ² Deceased. * [email protected] (DS); [email protected] (MKB) OPEN ACCESS Abstract Citation: Sandhu D, Ghosh J, Johnson C, In soybean, variegated flowers can be caused by somatic excision of the CACTA-type trans- Baumbach J, Baumert E, Cina T, et al. (2017) The posable element Tgm9 from Intron 2 of the DFR2 gene encoding dihydroflavonol-4-reduc- endogenous transposable element Tgm9 is suitable for generating knockout mutants for tase of the anthocyanin pigment biosynthetic pathway. DFR2 was mapped to the W4 locus, functional analyses of soybean genes and genetic where the allele containing Tgm9 was termed w4-m. In this study we have demonstrated improvement in soybean. PLoS ONE 12(8): that previously identified morphological mutants (three chlorophyll deficient mutants, one e0180732. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. male sterile-female fertile mutant, and three partial female sterile mutants) were caused by pone.0180732 insertion of Tgm9 following its excision from DFR2. -

An Everlasting Pioneer: the Story of Antirrhinum Research

PERSPECTIVES 34. Lexer, C., Welch, M. E., Durphy, J. L. & Rieseberg, L. H. 62. Cooper, T. F., Rozen, D. E. & Lenski, R. E. Parallel und Forschung, the United States National Science Foundation Natural selection for salt tolerance quantitative trait loci changes in gene expression after 20,000 generations of and the Max-Planck Gesellschaft. M.E.F. was supported by (QTLs) in wild sunflower hybrids: implications for the origin evolution in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA National Science Foundation grants, which also supported the of Helianthus paradoxus, a diploid hybrid species. Mol. 100, 1072–1077 (2003). establishment of the evolutionary and ecological functional Ecol. 12, 1225–1235 (2003). 63. Elena, S. F. & Lenski, R. E. Microbial genetics: evolution genomics (EEFG) community. In lieu of a trans-Atlantic coin flip, 35. Peichel, C. et al. The genetic architecture of divergence experiments with microorganisms: the dynamics and the order of authorship was determined by random fluctuation in between threespine stickleback species. Nature 414, genetic bases of adaptation. Nature Rev. Genet. 4, the Euro/Dollar exchange rate. 901–905 (2001). 457–469 (2003). 36. Aparicio, S. et al. Whole-genome shotgun assembly and 64. Ideker, T., Galitski, T. & Hood, L. A new approach to analysis of the genome of Fugu rubripes. Science 297, decoding life. Annu. Rev. Genom. Human. Genet. 2, Online Links 1301–1310 (2002). 343–372 (2001). 37. Beldade, P., Brakefield, P. M. & Long, A. D. Contribution of 65. Wittbrodt, J., Shima, A. & Schartl, M. Medaka — a model Distal-less to quantitative variation in butterfly eyespots. organism from the far East. -

Throughout the Maize Genome for Use in Regional Mutagenesis Judith M. Kolkman* , Liza J. Conrad

Genetics: Published Articles Ahead of Print, published on November 1, 2004 as 10.1534/genetics.104.033738 Distribution of Activator (Ac) Throughout the Maize Genome for Use in Regional Mutagenesis Judith M. Kolkman*1, Liza J. Conrad*†1, Phyllis R. Farmer*, Kristine Hardeman††, Kevin R. Ahern*, Paul E. Lewis*, Ruairidh J.H. Sawers*, Sara Lebejko††, Paul Chomet†† and Thomas P. Brutnell*2 *Boyce Thompson Institute, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853; †Department of Plant Breeding, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853; ††Monsanto/Mystic Research, Mystic, CT 06355 Sequence data from this article have been deposited with the EMBL/GenBank Libraries under accession nos. AY559172-AY559221, AY559223-AY559234, AY618471-AY618479 1 Running Head: Ac Insertion Sites in Maize Key words: transposition, transposon tagging, mutagenesis, Ac, maize 1 These authors contributed equally to this work. 2 Corresponding author: Thomas P. Brutnell Boyce Thompson Institute Cornell University 1 Tower Road Ithaca, NY 14853 Phone: 607-254-8656 Fax: 607-254-1242 email: [email protected] 2 ABSTRACT A collection of Activator (Ac) containing, near-isogenic W22 inbred lines has been generated for use in regional mutagenesis experiments. Each line is homozygous for a single, precisely positioned Ac element and the Ds reporter, r1-sc:m3. Through classical and molecular genetic techniques, 158 transposed Ac elements (tr-Acs) were distributed throughout the maize genome and 41 were precisely placed on the linkage map utilizing multiple recombinant inbred populations. Several PCR techniques were utilized to amplify DNA fragments flanking tr-Ac insertions up to 8 kb in length. Sequencing and database searches of flanking DNA revealed the majority of insertions are in hypomethylated, low or single copy sequences indicating an insertion site preference for genic sequences in the genome. -

Identification and Characterization of Breakpoints and Mutations on Drosophila Melanogaster Balancer Chromosomes

G3: Genes|Genomes|Genetics Early Online, published on September 24, 2020 as doi:10.1534/g3.120.401559 1 Identification and characterization of breakpoints and mutations on Drosophila 2 melanogaster balancer chromosomes 3 Danny E. Miller*, Lily Kahsai†, Kasun Buddika†, Michael J. Dixon†, Bernard Y. Kim‡, Brian R. 4 Calvi†, Nicholas S. Sokol†, R. Scott Hawley§** and Kevin R. Cook† 5 *Department of Pediatrics, Division of Genetic Medicine, University of Washington, and Seattle 6 Children's Hospital, Seattle, WA, 98105 7 †Department of Biology, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47405 8 ‡Department of Biology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305 9 §Department of Molecular and Integrative Physiology, University of Kansas Medical Center, 10 Kansas City, KS 66160 11 **Stowers Institute for Medical Research, Kansas City, MO 64110 12 ORCIDs: 0000-0001-6096-8601 (D.E.M.), 0000-0003-3429-445X (L.K.), 0000-0002-9872-4765 13 (K.B.), 0000-0003-0208-0641 (M.J.D.), 0000-0002-5025-1292 (B.Y.K.), 0000-0001-5304-0047 14 (B.R.C.), 0000-0002-2768-4102 (N.S.S.), 0000-0002-6478-0494 (R.S.H.), 0000-0001-9260- 15 364X (K.R.C.) 1 © The Author(s) 2020. Published by the Genetics Society of America. 16 Running title: Balancer breakpoints and phenotypes 17 18 Keywords: balancer chromosomes, chromosomal inversions, p53, Ankyrin 2, 19 Fucosyltransferase A 20 21 Corresponding author: Kevin R. Cook, Department of Biology, Indiana University, 1001 E. 22 Third St., Bloomington, IN 47405, 812-856-1213, [email protected] 23 2 24 ABSTRACT 25 Balancers are rearranged chromosomes used in Drosophila melanogaster to maintain 26 deleterious mutations in stable populations, preserve sets of linked genetic elements and 27 construct complex experimental stocks. -

483.Full.Pdf

Copyright 8 1988 by the Genetics Society for America Molecular Analysis of the Neurogenic Locus mastermind of Drosophila melanogaster Barry Yedvobnick, David Smoller, Pamela Young and Diane Mills Department of Biology, Emoq University, Atlanta, Georgia 30322 Manuscript received August 25, 1987 Revised copy accepted November 21, 1987 ABSTRACT The neurogenic loci comprise a small group of genes which are required for proper division between the neural and epidermal pathways of differentiation within the neuroectoderm. Loss of neurogenic gene function results in the misrouting of prospective epidermal cells into neuroblasts. A molecular analysis of the neurogenic locus mastermind (mam)has been initiated through transposon tagging with P elements. Employing the Harwich strain as the source of P in a hybrid dysgenesis screen, 6000 chromosomes were tested for the production of lethal mam alleles and eight mutations were isolated. The mam region is the site of residence of a P element in Harwich which forms the focus of a chromosome breakage hotspot. Hybrid dysgenic induced mum alleles elicit cuticular and neural abnormalities typical of the neurogenic phenotype, and in five of the eight cases the mutants appear to retain a P element in the cytogenetic region (50CD) of mum. Utilizing P element sequence as probe, mam region genomic DNA was cloned and used to initiate a chromosome walk extending over 120 kb. The physical breakpoints associated with the hybrid dysgenic alleles fall within a 60- kb genomic segment, predicting this as the minimal size of the mam locus barring position effects. The locus contains a high density of repeated elements of two classes; Opa (CAX), and (dC-dA), * (dG-dT),. -

Identification of the Maize Gravitropism Gene Lazy Plant1 by a Transposon-Tagging Genome Resequencing Strategy Thomas P

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Cell and Molecular Biology Faculty Publications Cell and Molecular Biology 2014 Identification of the Maize Gravitropism Gene lazy plant1 by a Transposon-Tagging Genome Resequencing Strategy Thomas P. Howard III Andrew P. Hayward See next page for additional authors Creative Commons License /"> This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication 1.0 License. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/cmb_facpubs Citation/Publisher Attribution Howard TP, Hayward AP, Tordillos A, Fragoso C, Moreno MA, Tohme J, Kausch AP, Mottinger JP, Dellaporta SL. (2014). "Identification of the maize gravitropism gene lazy plant1 by a transposon-tagging genome resequencing strategy." PLoS One. 9(1): e87053. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0087053 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Cell and Molecular Biology at DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cell and Molecular Biology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Thomas P. Howard III, Andrew P. Hayward, Anthony Tordillos, Christopher Fragoso, Maria A. Moreno, Joe Tohme, Albert P. Kausch, John P. Mottinger, and Stephen L. Dellaporta This article is available at DigitalCommons@URI: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/cmb_facpubs/12 Identification of the Maize Gravitropism Gene lazy plant1 by a Transposon-Tagging Genome Resequencing Strategy Thomas -

1471-2164-8-116.Pdf

BMC Genomics BioMed Central Research article Open Access Sequence-indexed mutations in maize using the UniformMu transposon-tagging population A Mark Settles*1, David R Holding2, Bao Cai Tan1, Susan P Latshaw1, Juan Liu3, Masaharu Suzuki1, Li Li1, Brent A O'Brien1, Diego S Fajardo1, Ewa Wroclawska1, Chi-Wah Tseung1, Jinsheng Lai4, Charles T Hunter III1, Wayne T Avigne1, John Baier1, Joachim Messing4, L Curtis Hannah1, Karen E Koch1, Philip W Becraft3, Brian A Larkins2 and Donald R McCarty1 Address: 1Horticultural Sciences Department, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA, 2Department of Plant Sciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA, 3Department of Genetics, Development and Cell Biology, Iowa State University, Ames, IA 50011, USA and 4Waksman Institute, Rutgers University, Piscataway, NJ 08854, USA Email: A Mark Settles* - [email protected]; David R Holding - [email protected]; Bao Cai Tan - [email protected]; Susan P Latshaw - [email protected]; Juan Liu - [email protected]; Masaharu Suzuki - [email protected]; Li Li - [email protected]; Brent A O'Brien - [email protected]; Diego S Fajardo - [email protected]; Ewa Wroclawska - [email protected]; Chi-Wah Tseung - [email protected]; Jinsheng Lai - [email protected]; Charles T Hunter - [email protected]; Wayne T Avigne - [email protected]; John Baier - [email protected]; Joachim Messing - [email protected]; L Curtis Hannah - [email protected]; Karen E Koch - [email protected]; Philip W Becraft - [email protected]; Brian A Larkins - [email protected]; Donald R McCarty - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 9 May 2007 Received: 29 August 2006 Accepted: 9 May 2007 BMC Genomics 2007, 8:116 doi:10.1186/1471-2164-8-116 This article is available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/8/116 © 2007 Settles et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd.