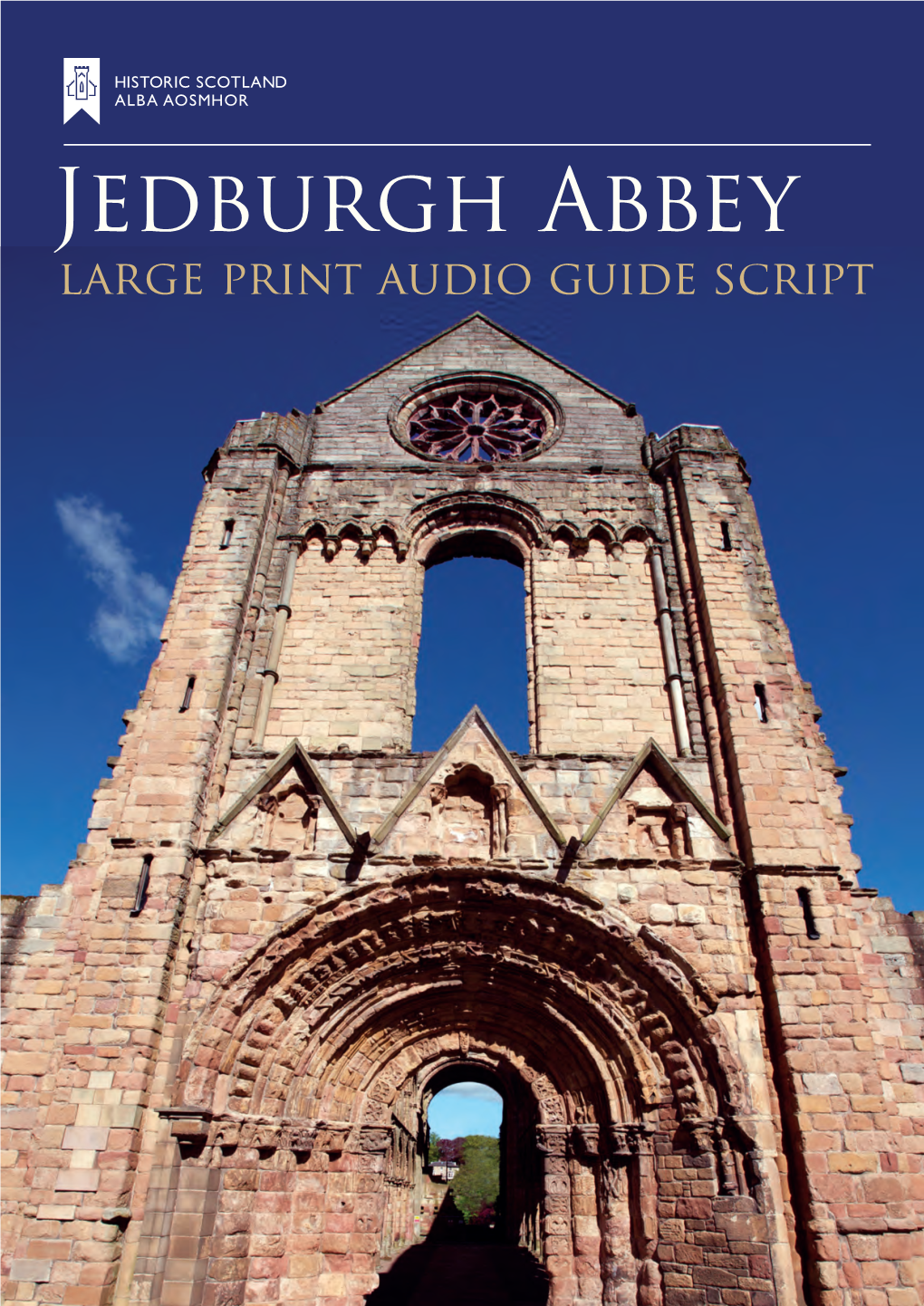

Jedburgh Abbey Large Text Audio Guide Script

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Invitation and Itinerary

The Scotland Borders England July 17-23, 2009 Invitation and Itinerary We hope you can join us in Scotland and England for exploration by bike of "The Borders" region of southern Scotland and northern England. In the guidebook Scotland the Best, The Borders is ranked as the #1 place to bike in Scotland. Touring by bike is the best venue we know for combining the outdoors, exercise, camaraderie among fellow cyclists, deliberately slow travels, and a dash of serendipitous adventure. We hold the fellowship and good times on past international tours as very special memories. Veterans and first time adventurers are encouraged to join us as we travel to an as yet undiscovered cycling paradise, before the word gets out! Mary and Allen Turnbull In 2009 Scotland will host its first ever Homecoming year which has been created to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Scotland’s national poet, Robert Burns. This will be a special year for Scots, those of Scotch ancestry, and all those who love Scotland. It will be fantastic year to "come home." www.homecomingscotland2009.com What is the best way to participate in this countrywide celebration? By bike, of course! So in July we will bike by ancient abbeys, castles, baronial mansions, gently flowing rivers, and picturesque villages as we start in western Scotland and end in England at the North Sea. The Borders include the four shires of Peebles, Berwick, Selkirk, and Roxburgh in Scotland, plus Northumberland in England. Insight Guides says "It [The Borders] is one of Europe’s last unspoilt areas." One morning we’ll put on our walking shoes and hike the Four Abbeys Way as we make a 21st Century pilgrimage to Jedburgh Abbey. -

Dryburgh Abbey Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC 141 Designations: Scheduled Monuent (90103); Listed building (LB15114); Garden and Designed Landscape (GDL00145) Taken into State care: 1919 (Ownership) Last reviewed: 2011 HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE DRYBURGH ABBEY We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH DRYBURGH ABBEY SYNOPSIS Dryburgh Abbey comprises the ruins of a Premonstratensian abbey, founded in 1150 by Hugh de Morville, constable of Scotland. The upstanding remains incorporate fine architecture from the 12th, 13th and 15th centuries. Following the Protestant Reformation (1560) the abbey passed through several secular hands, until coming into the possession of David Erskine, 11th earl of Buchan, who recreated the ruin as the centrepiece of a splendid Romantic landscape. Buchan, Sir Walter Scott and Field-Marshal Earl Haig are all buried here. While a greater part of the abbey church is now gone, what does remain - principally the two transepts and west front - is of great architectural interest. The cloister buildings, particularly the east range, are among the best preserved in Scotland. The chapter house is important as containing rare evidence for medieval painted decoration. The whole site, tree-clad and nestling in a loop of the River Tweed, is spectacularly beautiful and tranquil. -

Jedburgh Tow Ur H Town T N Trail

je d b u r gh t ow n t ra il . jed bu rgh tow n tr ail . j edburgh town trail . jedburgh town trail . jedburgh town trail . town trail . jedb urgh tow n t rai l . je dbu rgh to wn tr ail . je db ur gh to wn tra il . jedb urgh town trail . jedburgh town jedburgh je db n trail . jedburgh town trail . jedburgh urg gh tow town tr h t jedbur ail . jed ow trail . introductionburgh n tr town town ail . burgh trail jedb il . jed This edition of the Jedburgh Town Trail has be found within this leaflet.. jed As some of the rgh urgh tra been revised by Scottish Borders Council sites along the Trail are houses,bu rwe ask you to u town tra rgh town gh tow . jedb il . jedbu working with the Jedburgh Alliance. The aim respect the owners’ privacy. n trail . je n trail is to provide the visitor to the Royal Burgh of dburgh tow Jedburgh with an added dimension to local We hope you will enjoy walking Ma rk et history and to give a flavour of the town’s around the Town Trail P la development. and trust that you ce have a pleasant 1 The Trail is approximately 2.5km (1 /2 miles) stay in Jedburgh long. This should take about two hours to complete but further time should be added if you visit the Abbey and the Castle Jail. Those with less time to spare may wish to reduce this by referring to the Trail map which is found in the centre pages. -

Jedburgh Abbey Church: the Romanesque Fabric Malcolm Thurlby*

Proc SocAntiq Scot, 125 (1995), 793-812 Jedburgh Abbey church: the Romanesque fabric Malcolm Thurlby* ABSTRACT The choir of the former Augustinian abbey church at Jedburgh has often been discussed with specific reference to the giant cylindrical columns that rise through the main arcade to support the gallery arches. This adaptation Vitruvianthe of giant order, frequently associated with Romsey Abbey, hereis linked with King Henry foundationI's of Reading Abbey. unusualThe designthe of crossing piers at Jedburgh may also have been inspired by Reading. Plans for a six-part rib vault over the choir, and other aspects of Romanesque Jedburgh, are discussed in association with Lindisfarne Priory, Lastingham Priory, Durham Cathedral MagnusSt and Cathedral, Kirkwall. The scale church ofthe alliedis with King David foundationI's Dunfermlineat seenis rivalto and the Augustinian Cathedral-Priory at Carlisle. formee e choith f Th o rr Augustinian abbey churc t Jedburgha s oftehha n been discussee th n di literature on Romanesque architecture with specific reference to the giant cylindrical columns that rise through the main arcade to support the gallery arches (illus I).1 This adaptation of the Vitruvian giant order is most frequently associated with Romsey Abbey.2 However, this association s problematicai than i e gianl th t t cylindrical pie t Romsea r e th s use yi f o d firse y onlth ba t n yi nave, and almost certainly post-dates Jedburgh. If this is indeed the case then an alternative model for the Jedburgh giant order should be sought. Recently two candidates have been put forward. -

Download Download

Proc Soc Antiq Scot 139 (2009), 257–304GRAVEHEART: CULT AND BURIAL IN A CISTERCIAN CHAPTER HOUSE | 257 Graveheart: cult and burial in a Cistercian chapter house – excavations at Melrose, 1921 and 1996 Gordon Ewart,* Dennis Gallagher† and Paul Sherman‡ with contributions from Julie Franklin, Bill MacQueen and Jennifer Thoms ABSTRACT The chapter house at Melrose was first excavated by the Ministry of Works in 1921, revealing a sequence of burials including a heart burial, possibly that of Robert I. Part of the site was re-excavated in 1996 by Kirkdale Archaeology for Historic Scotland in order to provide better information for the presentation of the monument. This revealed that the building had expanded in the 13th century, the early chamber being used as a vestibule. There was a complex sequence of burials in varied forms, including a translated bundle burial and some associated with the cult which developed around the tomb of the second abbot, Waltheof. The heart burial was re-examined (and reburied) and its significance is considered in the context of contemporary religious belief and the development of a cult. There was evidence for an elaborate tiled floor, small areas of which survive in situ. INTRODUCTION invitation of King David I. Under its first abbot, Richard (1136–48), the community rapidly The chapter house at Melrose Abbey (NGR: expanded and royal support for their austere NT 5484 3417; illus 1 and 2) was excavated life led to the founding of a daughter house at first in 1921 by the Ministry of Works as part of Newbattle in 1140, soon to be followed by other an extensive clearance of the monastic remains houses (Cowan & Easson 1976, 72). -

The Rutherfurds of That Ilk, and Their Cadets

nII 1 HI Hlfe& Mmm v^* IS, il not BBBB life JtatWiir&s jtf tfcrat Ilk. 11 J/4L. GL National Library of Scotland *B000419873* /Mtf Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/rutherfurdsofthaOOruth . NORMAN DOOR. JEDBURGH ABBEY—Entrance to the Burial-Place of the RoiHiamEDs PEDIGREE OF if RUTHERFOORD, LORD RUTHERFOORD. EDINBURGH : SCOTT AND FERGUSON, AND BURNESS AND COMPANY, PRINTERS TO HER MAJESTY. a THE RUTHERFURDS of that ILK, AND THEIR CADETS. COMPILED FROM THE PUBLIC RECORDS AND OTHER AUTHENTIC SOURCES. i! Co-dd U/\/K - J4&*d>. J )\Lm llavy^ (* LIBRARY^ EDINBURGH. 1884. TO WILLIAM ALEXANDER OLIVER-RUTHIRFURD, ESQUIRE OF EDGERSTON, ARE INSCRIBED THESE NOTES AND PEDIGREE OF THE RUTHIRFURDS, BY A FRIEND. PREFACE. The Records of a family that has helped to make Scottish History, and has produced many distinguished men, are worthy of pre- servation. Those who take an interest in Border story, although unconnected with the not very worldly wise—as regarded their own aggran- disement—but brave and loyal race of Ruthir- furd, may consider the labour expended in this endeavour to trace the descent of the various families of the name, not altogether unserviceable. Professed Genealogists will, he hopes, be lenient to the shortcomings of a mere amateur, who takes this opportunity of tendering his best thanks to Mr. Oliver-Ruthirfurd of that Ilk and Edgerston, to whom he inscribes these Notes and Pedigree, for his friendly help in affording him access to the Edgerston and Hunthill family documents, to which he owes much otherwise unattainable information. -

Scotland ; Picturesque, Historical, Descriptive

t=3 V^\ » JEDBURGH ABBEY. 225 sixth Duke, who succeeded his father in 1823, it would be superfluous to attempt a description. The additions to this grand mansion render the edifice of great extent, and the situation is one of the most delightful in the vicinity of " pleasant Teviotdale." JEDBURGH ABBEY. Jedbukgh, the country town of Roxburgh, and a royal burgh, is two miles aoove the influx of the river Jed with the Tweed, ten miles from Kelso, and forty-six miles by Lauder from Edinburgh. The ancient name was Jedworth, and the district was known as the Forest of Jedworth ; but another Jedworth represented by a hamlet called Old Jedworth, is about five miles farther up the vales of the Jed. 1 The origin of the burgh, like that of many others, was the Castle of Jedburgh, the founder of which is unknown. This extinct edifice was one of the favourite residences of David I., who by the advice of his preceptor John, also designated Achaius, afterwards Bishop of Glasgow, induced a colony of Canons-Regular, or Augustines, of the Order of St. Augustine, Bishop of Hippo, from the Abbey of St. Quentin at Beauvais in the department of the Oise, to settle at Jedworth near his Castle. The exact date is variously stated in 11 18 and 1147." The first may be the year of the arrival of the Canons, and the second that of the foundation of the Abbey, which was at first a Priory. Few particulars are recorded of the Abbots of Jedburgh, whose names are involved in obscurity. -

Four Abbeys Cycleway

FOUR ABBEYS CYCLEWAY SELF GUIDED CYCLING HOLIDAY FOUR ABBEYS CYCLEWAY - SELF GUIDED CYCLING HOLIDAY SUMMARY Immerse yourself in the moment on this gentle, undemanding cycle tour through the rolling pastoral landscape of the Scottish Borders. Take time to visit the medieval abbeys at Melrose and its neighbour Dryburgh, onto Kelso and finally Jedburgh, learning about the tumultuous and sometimes bloody history of this often disputed territory. The Four Abbeys Cycleway itinerary is a circuit, starting at the charming Border town of Melrose. Each cycling day has been specially designed to ensure a relaxed pace, allowing you to experience all that this feature filled cycling holiday has to offer. Along the way you pass scenic viewpoints overlooking lush green valleys and visit historic landmarks. You will learn how the area grew during the medieval renaissance, prospering from monastic trade links and cultural exchanges with Europe and its scholars. The route offers castles, towers, country houses and gardens. Cycling at the foot of Eildon Hills, otherwise known as the ‘magic mountains’ and rich in folklore, the Teviot and Tweed rivers will never be far from your side. The Borders region offers an abundance of local produce and you’ll be tempted to try the local goodies as you pass the tea rooms, farmers markets, Tour: Four Abbeys Cycleway and historic towns. Code: CSSFA1 Type: Self-Guided Cycling Holiday HIGHLIGHTS Price: See Website Dates: March—October See the best of the Borders tranquil countryside Nights: 4 / Days: 5 Discover the turbulent history behind each of the four medieval Abbeys Cycling Days: 3 Spectacular views across the magical Eildon Hills Start/Finish: Melrose Distance: 100 Miles (160 kms) Enjoy wonderful and varied mouth-watering local fayre along the route Grade: Easy Visit Floors Castle with its collection of period furniture, tapestries and artworks IS IT FOR ME? WHY CHOOSE A SELF GUIDED CYCLING HOLIDAY WITH US? This holiday will appeal to anyone who can Macs Adventure are specialists in self guided walking and cycling holidays. -

The SCOTTISH BORDERS

EXPLORE 2020-2021 The SCOTTISH BORDERS visitscotland.com Contents 2 The Scottish Borders at a glance 4 A creative hub 6 A dramatic past 8 Get active outdoors 10 Discover Scotland’s leading cycling destination 12 Local flavours 14 Year of Coasts and Waters 2020 16 What’s on 18 Travel tips 20 Practical information 24 Places to visit 41 Leisure activities 46 Shopping Welcome to… 49 Food & drink 52 Accommodation THE SCOTTISH 56 Regional map BORDERS Step out into the rolling hills, smell the spring flowers in the forest, listen to the chattering river and enjoy the smiles of the people you meet. Welcome to the Scottish Borders, a very special part of the country that will captivate you instantly. Here you’ll find wild, wide-open landscapes, a buzzing cultural scene, a natural larder to die for and outdoor activities for the most adventurous of thrill-seekers. The Scottish Borders is also a place where the past lives Cover: Kelso Abbey around us – in ancient abbeys, historic Above image: Mellerstain House, walking routes and the stories told by the near Kelso people you’ll meet. Discover the wealth of incredible experiences in the forests and Credits: © VisitScotland. along the coastline of the Scottish Borders – Kenny Lam, Ian Rutherford, get active, discover great attractions and have Paul Tomkins, Johnstons of Elgin/ an adventure! Angus Bremner, David N Anderson, Cutmedia, David Cheskin 20SBE Hawico Factory Visitor Centre Kelso Outlet Store Arthur Street 20 Bridge Street Produced and published by APS Group Scotland (APS) in conjunction with VisitScotland (VS) and Highland News & Media (HNM). -

The Bloody Buffer State

The Bloody Buffer State Rough Wooing - Background Because the ancient Kingdom of Bernicia had stretched from the Forth to the Tyne, kings of both England and Scotland had claimed Northumberland as theirs. The Treaty of York in 1237 effectively settled the borderline between England and Scotland with the formation of East, Middle and West Marches. For centuries the northern English and the southern Scots pillaged among their neighbours and developed their own system of thieving and armed thuggery that has been called reiving. The whole system fi nally fell apart when James VI inherited the throne of England on the death of Queen Elizabeth in 1603 and the anarchy among the families on both sides of the Borders could be quashed. The 16th century was the bloodiest in the history of the Borders and the bloodiest period of that bloody century was 1544-47 in what became known as England’s Rough Wooing. There were three campaigns, those in 1544 and 1547 were largely against Edinburgh and the Lothians. In 1513, England was fi ghting France in Flanders. France, desperate for a diversion, appealed to James IV to attack England from the north and James responded by fi elding the largest army Scotland had every seen – between 60,000 and 100,000 men. By the time the two armies met at Flodden in Northumberland, the English had already routed the French in Flanders and now proceeded, under the Earl of Surrey, to annihilate the Scots. James IV, his bastard son Alexander, 13 earls and thousands of lesser ranks were killed. -

Wallace, Iain Ross (2020) Leaving a Mark on History. the Stonemasons’ Marks of Selected Medieval Ecclesiastical and Secular Buildings of Central and Southern Scotland

Wallace, Iain Ross (2020) Leaving a mark on history. The stonemasons’ marks of selected medieval ecclesiastical and secular buildings of central and southern Scotland. MRes thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/81713/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Leaving a mark on history The stonemasons’ marks of selected medieval ecclesiastical and secular buildings of central and southern Scotland. Volume 1 Iain Ross Wallace Cert HE, MA Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters (Research) in Archaeology School of Humanities, College of Arts, University of Glasgow. September 2019 © Iain Ross Wallace Leaving a mark on history Abstract Our knowledge and understanding of medieval buildings in Scotland, and indeed elsewhere, is influenced by the historical record, which invariably focuses on those at the upper echelons of society who ordered their construction and then occupied the buildings. This multi-disciplinary research has investigated the stonemasons’ marks found on selected medieval stone buildings in central and southern Scotland which were begun in the 12th and 13th centuries. -

Walking the Borders Abbeys Way, 2017

Walking the Borders Abbeys Way, 2017 By Christine McNaughton My friend, and regular walking companion, Marjorie have, over the past few years, walked several long-distance routes. For 2017 we decided on The Borders Abbeys Way, a 68 mile-long route linking the abbey towns in the Scottish Borders. We decided to make Melrose our base for the week so booked into a hotel along with my husband John and several friends. L to R: John & Christine McNaughton & Marjorie at Melrose Abbey. The Temple of the Muses. Day 1: On the first day we drove up to Melrose in the morning, and after registering at the hotel, we made our way to Melrose. The Abbey was founded in 1136 by the monks of the Cistercian Order at the request of David I of Scotland and several Scottish Kings are buried there. In 1921 a lead container believed to hold the embalmed heart of Robert the Bruce was found under the Chapter House. From here we would walk the six miles to Dryburgh Abbey. John walked with us on this section, and after going along the ancient Priors Walk (a route used by the masons during the building of the Abbey) we reached the Rhymer’s Stone. This marks the place where the Eildon Tree once stood, and where Thomas Rhymer is said to have met the Queen of Fairies and delivered prophecies in the 13th century. A few miles on we made a small detour to see the Temple of the Muses. This circular neo-classical “temple” is dedicated to James Thompson (1700-1748) poet, and was erected by David Stuart Erskine, 11th Earl of Buchan.