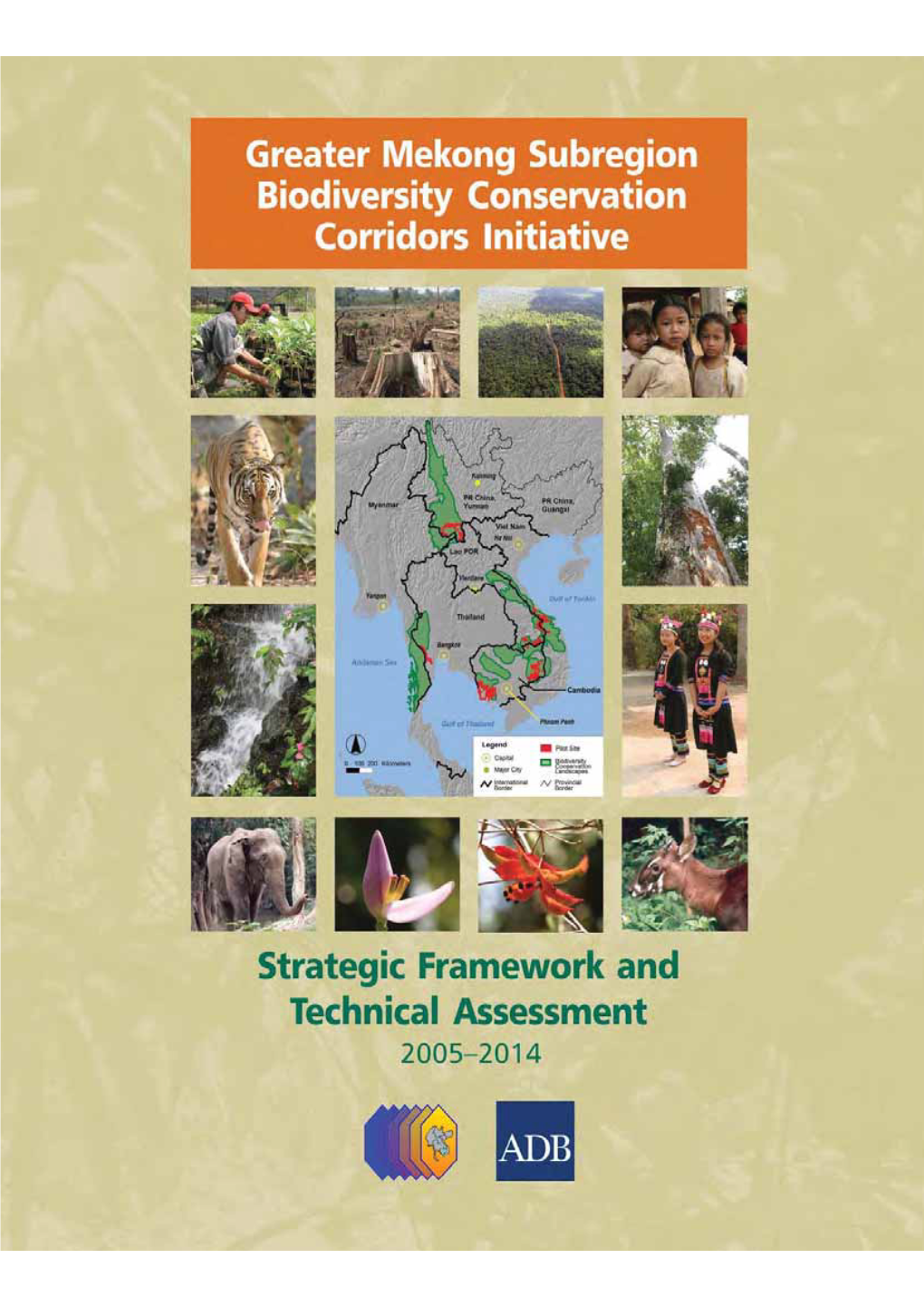

BCCI Strategic Framework and Technical Assessment 2005-2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of Connecting Plants and People

THE NEWSLEttER OF THE SINGAPORE BOTANIC GARDENS VOLUME 34, JANUARY 2010 ISSN 0219-1688 of connecting plants and people p13 Collecting & conserving Thai Convolvulaceae p2 Sowing the seeds of conservation in an oil palm plantation p8 Spindle gingers – jewels of Singapores forests p24 VOLUME 34, JANUARY 2010 Message from the director Chin See Chung ARTICLES 2 Collecting & conserving Thai Convolvulaceae George Staples 6 Spotlight on research: a PhD project on Convolvulaceae George Staples 8 Sowing the seeds of conservation in an oil palm plantation Paul Leong, Serena Lee 12 Propagation of a very rare orchid, Khoo-Woon Mui Hwang, Lim-Ho Chee Len Robiquetia spathulata Whang Lay Keng, Ali bin Ibrahim 150 years of connecting plants and people: Terri Oh 2 13 The making of stars Two minds, one theory - Wallace & Darwin, the two faces of evolution theory I do! I do! I do! One evening, two stellar performances In Search of Gingers Botanical diplomacy The art of botanical painting Fugitives fleurs: a unique perspective on floral fragments Falling in love Born in the Gardens A garden dialogue - Reminiscences of the Gardens 8 Children celebrate! Botanical party Of saints, ships and suspense Birthday wishes for the Gardens REGULAR FEATURES Around the Gardens 21 Convolvulaceae taxonomic workshop George Staples What’s Blooming 18 22 Upside down or right side up? The baobab tree Nura Abdul Karim Ginger and its Allies 24 Spindle gingers – jewels of Singapores forests Jana Leong-Škornicková From Education Outreach 26 “The Green Sheep” – a first for babies and toddlers at JBCG Janice Yau 27 International volunteers at the Jacob Ballas Children’s Garden Winnie Wong, Janice Yau From Taxonomy Corner 28 The puzzling bathroom bubbles plant.. -

Development Plan for Tonle Sap and Chakdomuk

DEVELOPMENT PLAN FOR TüNLE SAP AND CHAKDOMUK PHASE 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY PREPARt:D FOI~ THE MEKONG SECRETARIAT BY ORS TOM IN ASSOCIATION WITH B C E 0 M OCTOBER 1993 BCEOM DEVELOPMENT PLAN FOR TONLE SAP AND CHAKDOMUK PHASE 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY prepared for The Mekong Secretariat by ORSTOM in association with BCEOM October 1993 SCOPE Of THE STUDY The Great Lake of Cambodia is the largest permanent freshwater lake in Southeast Asia, covering areas between 2 500 km 2 during the dry season and more than 13 000 km 2 at the end of the rainy season. The Great Lake is connected to the Mekong by the Tonlé Sap River. The confluence is at Chakdomuk in Phnom Penh city, some 120 km to the south-west of the outlet of the lake. The study area (éomprising the Great Lake, the Tonlé Sap River and their surrounding wetlands and agricultural fields) constitutes a highly productive ecosystem for the country. However, several reports have indicated that environmental conditions have changed during the last years. The siltation of the Tonlé Sap, especially at the confluence with the Mekong and at the entrance of the lake (near Snoc Trou) was reported as being an obstacle to the flow in the Tonlé Sap River. It was also alleged that sedimentation has significantly reduced the depth of the lake. Serious reduction in fish catches have also been reported. Sedimentation and uncontrolled fishing practices are thought to be major causes for this reduction. The Interim Committee for Coordination of Investigations of the Lower Mekong Basin resolved to address these problems, including inland navigation aspects and river morphology problems in the confluence area of Chakdomuk, through a comprehensive integrated development plan of the area. -

Mekong River in the Economy

le:///.le/id=6571367.3900159 NOVEMBER REPORT 2 0 1 6 ©THOMAS CRISTOFOLETTI / WWF-UK In the Economy Mekong River © NICOLAS AXELROD /WWF-GREATER MEKONG Report prepared by Pegasys Consulting Hannah Baleta, Guy Pegram, Marc Goichot, Stuart Orr, Nura Suleiman, and the WWF-Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and Vietnam teams. Copyright ©WWF-Greater Mekong, 2016 2 Foreword Water is liquid capital that flows through the economy as it does FOREWORD through our rivers and lakes. Regionally, the Mekong River underpins our agricultural g systems, our energy production, our manufacturing, our food security, our ecosystems and our wellbeing as humans. The Mekong River Basin is a vast landscape, deeply rooted, for thousands of years, in an often hidden water-based economy. From transportation and fish protein, to some of the most fertile crop growing regions on the planet, the Mekong’s economy has always been tied to the fortunes of the river. Indeed, one only need look at the vast irrigation systems of ancient cities like the magnificent Angkor Wat, to witness the fundamental role of water in shaping the ability of this entire region to prosper. In recent decades, the significant economic growth of the Lower Mekong Basin countries Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and Viet Nam — has placed new strains on this river system. These pressures have the ability to impact the future wellbeing including catalysing or constraining the potential economic growth — if they are not managed in a systemic manner. Indeed, governments, companies and communities in the Mekong are not alone in this regard; the World Economic Forum has consistently ranked water crises in the top 3 global risks facing the economy over the coming 15 years. -

Boundary & Territory Briefing

International Boundaries Research Unit BOUNDARY & TERRITORY BRIEFING Volume 2 Number 6 The Land Boundaries of Indochina: Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam Ronald Bruce St John Boundary and Territory Briefing Volume 2 Number 6 ISBN 1-897643-32-2 1998 The Land Boundaries of Indochina: Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam by Ronald Bruce St John Edited by Clive Schofield International Boundaries Research Unit Department of Geography University of Durham South Road Durham DH1 3LE UK Tel: UK + 44 (0) 191 334 1961 Fax: UK +44 (0) 191 334 1962 E-mail: [email protected] www: http://www-ibru.dur.ac.uk The Author Ronald Bruce St John is an independent scholar specialising in the political economy and foreign policy of developing states. He has worked as an advisor and researcher in Southeast Asia for almost 30 years and remains a regular visitor to Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. He holds a B.A. in political science from Knox College and an M.A. and Ph.D. in international relations from the Graduate School of International Studies, University of Denver. Dr St John has published widely on Asian issues, including recent articles in Asian Survey, Asian Affairs, Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars, Contemporary Southeast Asia, and Journal of the Siam Society. He is the author of two earlier Boundary and Territory Briefings, The Boundary Between Ecuador and Peru and The Bolivia-Chile-Peru Dispute in the Atacama Desert. Dr St John is currently completing a major study of economic reform and economic development in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. The opinions and comments contained herein are those of the author and are not necessarily to be construed as those of the International Boundaries Research Unit. -

Country Report L a O P

Country Report Lao PDR Natural Disaster Risk Assessment and Area Business Continuity Plan Formulation for Industrial Agglomerated Areas in the ASEAN Region March 2015 AHA CENTRE Japan International Cooperation Agency OYO International Corporation Mitsubishi Research Institute, Inc. CTI Engineering International Co., Ltd. Overview of the Country Basic Information of Lao PDR 1), 2), 3) National Flag Country Name Long form : Lao People's Democratic Republic Short form : Lao PDR, Laos Capital Vientiane Area (km2) Total: 236,800 Land: 230,800 Inland Water: 6,000 Population 6,769,727 Population density(people/ km2 of land area) 29 Population growth (annual %) 1.8 Urban population (% of total) 36 Languages Lao Ethnic Groups There are 49 ethnic groups including Lao (at least half of the total population) Religions Buddhism GDP (current US$) (billion) 11 GNI per capita, PPP (current international $) 4,570 GDP growth (annual %) 8.1 Agriculture, value added (% of GDP) 28 Industry, value added (% of GDP) 36 Services, etc., value added (% of GDP) 36 Brief Description Laos is located on the Indochina Peninsula, and bordered by China to the north, Myanmar to the west, Vietnam to the east, and Cambodia and Thailand to the south. It is the only landlocked country in ASEAN. The Mekong River runs north-south across Laos. The country is also characterized by its large mountainous regions. Laos became a member of ASEAN on July 23, 1997, together with Myanmar. Unlike other ASEAN countries, Laos does not have a large metropolis, and the country is thinly populated. Laos is a People’s Democratic Republic, and Choummaly Sayasone is the President and the head of state of Laos. -

Senate Set to Decide on Covid Law

WEDNESDAY, MARCH 10, 2021 Intelligent . In-depth . Independent Issue Number 3623 / 4000 RIEL Senate set to decide on Covid law Niem Chheng and Mom Kunthear in the hands of the commission on The draft law was proposed by the trol law to contain the pandemic and defines legal measures to prevent the health, social affairs, youth rehabili- government on February 28 and passed urged the Senate to speedily pass it. spread of Covid-19,” Hun Sen said. HE Senate will hold an tation, labour, vocational training, by the National Assembly on March 5 “I request that the Senate presi- Bun Neang said: “The law will be extraordinary session on and women’s affairs for a review. following the February 20 community dent, acting as head of state, find a passed no later than five days because March 11 to approve the The commission will then refer the outbreak of Covid-19, which had seen way to swiftly enact the draft law that Article 113 of the Constitution states draft law on the control of draft law to the Permanent Commit- confirmed cases rise to 549 in just over the National Assembly has recently that the Senate can pass a draft law Covid-19T and other contagious dis- tee on March 10, with a full Senate two weeks as of March 9. passed. Please hold an online session deemed urgent by the National As- eases, with the bill expected to be session expected the next day. Once In an urgent public address late on or a meeting with a limited number of sembly within five days of its receipt. -

Page 1 Nat. Hist. BULL. SIAM Soc. 38: 135-161, 1990 ECOLOGY AND

NAT. NAT. HIST. BUL L. SIAM Soc. 38: 135-161 ,1990 ECOLOGY AND BEHA VIOR OF KITT I' S HOG-NOSED BAT (CRASEONYCTERIS THONGLONGYA 刀IN WESTERN THAILAND Surapon Duangkhae* ABSTRACT The The and ecology behavior of a colony of Craseonycleris Ihonglongyai was studied during during November ,1984 to May , 1986. Craseonycleris was found to have two short foraging periods ,one around dawn and another at dusk. Th e mean duration of activity was 18 min in the moming moming and 30 min in the evening. The bats used specific flyways to reach their foraging areas which which were less than 1km from the cave. The numbers ofbats using each flyway changed daily and and seasonally. The foraging periods of the bats als ら seasonally. varied Craseonycleris appeared appeared very sensitive to changes in environmental conditions; low temperature and heavy rains rains inhibited foraging activity Recommendations Recommendations and guidelines are given conceming minimizing disturbance to the the roosting caves and foraging areas ,future research , and the establishment of a long term population population monitoring program 飢 d an education center. INTRODUCTION Kitti's Kitti's Hog-nosed bat (C ・raseonycteris thonglongy αi) was discovered in 1973 by Kitti Kitti Thonglongya , in a cave near Sai Yok Waterfa l1, Kanchanaburi Province ,westem Thailand Thailand (Figs. 1 and 2). At that time he co l1 ected 52 bats from the cave (THONGLONGY A , 1973). 1973). In the month fo l1 owing discovery ofthe bat ,Kitti Th onglongya explored about 50 more caves caves along the Khwae Noi River (River Khwae) but no more bats were found. -

Preliminary Gibbon Status Review for Lao PDR 2008

Preliminary Gibbon Status Review for Lao PDR 2008 J.W. Duckworth December 2008 This work was carried out with funding from the Arcus Foundation. Preliminary gibbon status review for Lao PDR 2008 This review is a work in progress for the conservation of gibbons in Lao PDR. It is intended to be updated periodically. Any comment on this document, including further records, would be gratefully received by the author and by Fauna & Flora International, at the addresses below. Citation: J. W. Duckworth, 2008, Preliminary gibbon status review for Lao PDR 2008, Fauna & Flora International, Unpublished report. Author: J. W. Duckworth, PO Box 5773, Vientiane, Lao PDR Email: [email protected] Date: December 2008 For more information or to send further comments contact: Paul Insua-Cao Fauna & Flora Asia-Pacific Programme, 340 Nghi Tam, Hanoi, Vietnam Tel: +84-(0)43-719 4117 Fax: +84-(0)43-719 4119 Email: [email protected] Front cover photo of a captive young yellow-cheeked crested gibbon by Monty Sly. All views expressed within are the author’s alone unless attributed otherwise and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of Fauna & Flora International. While the authors and editors strive for rigour and accuracy in presenting this report, Fauna & Flora International make no representations as to completeness, suitability or validity of any information contained, and will not be liable for any errors or omissions. The editors and Fauna & Flora International take no responsibility for any misrepresentation of material resulting from translation of this report into any other language. Reproduction of any part of this report for educational, conservation and other non-profit purposes is authorised without prior permission from the copyright holder, provided that the source is fully acknowledged. -

Assessment of Greater Mekong Subregion Economic Corridors

About the Assessment of Greater Mekong Subregion Economic Corridors The transformation of transport corridors into economic corridors has been at the center of the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) Economic Cooperation Program since 1998. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) conducted this Assessment to guide future investments and provide benchmarks for improving the GMS economic corridors. This Assessment reviews the state of the GMS economic corridors, focusing on transport infrastructure, particularly road transport, cross-border transport and trade, and economic potential. This assessment consists of six country reports and an integrative report initially presented in June 2018 at the GMS Subregional Transport Forum. About the Greater Mekong Subregion Economic Cooperation Program The GMS consists of Cambodia, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Myanmar, the People’s Republic of China (specifically Yunnan Province and Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region), Thailand, and Viet Nam. In 1992, with assistance from the Asian Development Bank and building on their shared histories and cultures, the six countries of the GMS launched the GMS Program, a program of subregional economic cooperation. The program’s nine priority sectors are agriculture, energy, environment, human resource development, investment, telecommunications, tourism, transport infrastructure, and transport and trade facilitation. About the Asian Development Bank ADB is committed to achieving a prosperous, inclusive, resilient, and sustainable Asia and the Pacific, while sustaining -

Part Iii Hydro-Hydraulic Modelling

PART III HYDRO-HYDRAULIC MODELLING Vol. I: Main Report, Part III: Hydro-Hydraulic Modelling WUP-JICA, March 2004 PART III HYDRO-HYDRAULIC MODELLING 1. DEVELOPMENT OF HYDRO-HYDRAULIC MODEL FOR THE CAMBODIAN FLOODPLAINS 1.1 Background of Model Development This Part III of the Main Report outlines all modelling activities carried out during the entire period of the WUP-JICA project/study including the model origin in the Mekong Basin and a similar improvement in the related project. In the initial stage of the study, some hydro-hydraulic simulation models were needed simultaneously with the monitoring activities to verify the observed data and to clarify the hydrological or hydraulic mechanisms in the basin. After a series of discussions with the MRCS due to the apprehension on overlapping of activities with the WUP-A and WUP-FIN projects, the WUP-JICA Team had decided to take over and further develop the model developed by the recently completed project of MRC. A brief description of the first study on the Mekong where MIKE 11 has been applied applied and the link to the other project where the model was used simultaneously with the WUP-JICA study for detailed flood analysis is herein presented. The part also explains the concepts of the two model systems applied; namely, the rainfall-runoff model and the hydraulic river and floodplain model. The coupling of the two models was studied as well. A detailed description of the topographical and structural data used for model construction is herein given, the hydrological and hydraulic data applied for model calibration or verification is described, and the detailed layout of the models together with the calibration or verification results for the years 1998-2001 is presented. -

Xe!Kong!Basin!

! ! Sustainable!Hydropower!Development!in!the! Xe!Kong!Basin!of!Lao!PDR:!Crafting!a!“Master!Plan”! ! Scope!of!Work! ! Revised!November!15,!2016! ! Executive!Summary! ! ! Lao!PDR!is!the!nation!with!the!most!experience!in!hydropower!development!in! Southeast!Asia,!with!even!larger!future!potential!and!intensions.!!For!the!future!facilities,!the! choices!regarding!the!siting,!design!and!operation!will!be!governed!by!the!new!Policy!on! Sustainable!Hydropower!Development!that!was!decreed!by!the!Prime!Minister!on!January!12,! 2015.!!! ! ! In!consultation!with!the!Ministry!of!Energy!and!Mines!and!other!relevant!agencies!of!the! Government!of!Lao,!the!Natural!Heritage!Institute!will!produce!a!sustainable!hydropower! development!“master!plan”!to!assist!and!guide!the!Government!of!Lao!PDR!in!that!Policy,! without!sacrificing!its!development!goals.!!!This!work!is!undertaken!under!an!Operations!Permit! issued!by!the!Ministry!of!Foreign!Affairs!and!will!be!conducted!under!a!Memorandum!of! Understanding!with!the!National!University!of!Lao!and!in!ongoing!consultation!with!all!of!the! agencies!of!the!government!of!Lao!PDR!that!exercise!authority!over!hydropower,!river!basin! development,!and!fisheries!administration.! ! ! In!the!Mekong!River!Basin,!the!principal!sustainability!consideration!in!hydropower! development!is!the!avoidance!of!impairment!of!the!exceptional!productivity!of!the!Mekong! fishery.!!Therefore,!the!“master!plan”!will!take!account!of,!but!greatly!improve!on,!the!several! previous!hydropower!development!plans!that!have!been!promulgated!by!JICA,!among!others,!by! -

Assessing Environmental Governance in the Lower Mekong River Basin: a Study of the Hydropower Site Selection Process in the Se San and Sre Pok Basins

ASSESSING ENVIRONMENTAL GOVERNANCE IN THE LOWER MEKONG RIVER BASIN: A STUDY OF THE HYDROPOWER SITE SELECTION PROCESS IN THE SE SAN AND SRE POK BASINS Vikrom Mathur Mak Sitirith Joakim Öjendal1 1. Introduction This case study has been undertaken within the Mekong Regional Environmental Governance project, which is an integral part of the Resource Policy Support Project (REPSI).2 The study will analyse issues related to regional governance of natural resources, and in particular the role of key institutions and organizations. The specific empirical focus of the case study is to understand the hydropower site selection process in the Se San and Sre Pok basins (see map), in the upland areas on the border of Laos, Vietnam, and Cambodia. It aims to understand the role of various actors in the site selection process and to evaluate to what extent the existing institutional processes have been (and are) adequate for promoting sustainable environmental governance. The outcome is an analysis of the process of hydropower site selection, which brings to light the forces exerted by the different actors and institutional structures that have had an impact on the end-result. The Mekong River Commission (MRC) Agreement, and its signatory institutions, is the key institution under scrutiny, but the study also evaluates the role of other key actors and institutions vis-à-vis the MRC. 1.1 Rationale and Relevance—Why this Particular Case Study? The case study’s particular focus, hydropower development in the Se San Basin, is a sensitive issue. Regional environmental governance has gained prevalence and urgency in the last couple of years in the Lower Mekong River Basin in relation to already implemented, as well as planned, (hydropower) interventions.