Stock Structure of Aleutian Island Golden King Crab

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pribilof Islands Golden King Crab May 2012 Crab SAFE Report Chapter

Pribilof Islands Golden King Crab May 2012 Crab SAFE Report Chapter (25 April 2012 Draft) Douglas Pengilly, ADF&G, Kodiak Executive Summary 1. Stock: Pribilof Islands (Pribilof District) golden king crab Lithodes aequispinus 2. Catches: Commercial fishing for golden king crab in the Pribilof District has been concentrated in the Pribilof Canyon. The fishing season for this stock has been defined as a calendar year (as opposed to a “crab fishery year”) following the close of the 1983/84 season. The domestic fishery developed in the 1982/83 season, although some limited fishing occurred at least as early as 1981/82. Peak harvest occurred in the 1983/84 season with a retained catch of 0.856-million pounds (388 t) by 50 vessels. Since then, participation in the fishery has been sporadic and annually retained catch has been variable, from 0 pounds in the nine years that no vessels participated (1984, 1986, 1990–1992, 2006–2009) up to a maximum of 0.342-million pounds (155 t) in 1995, when seven vessels made landings. The fishery is not rationalized. There is no state harvest strategy in regulation. A guideline harvest level (GHL) was first established for the fishery in 1999 at 0.200-million pounds (91 t) and has been managed towards a GHL of 0.150- million pounds (68 t) since 2000. No vessels participated in the directed fishery and no landings were made during 2006–2009. One vessel landed catch in 2010 and two vessels landed catch in 2011; directed fishery catch cannot be reported in those two years under the confidentiality requirements of Sec. -

Biological Perspectives on Crab Management in Alaska: an Oral Report to the Alaska Board of Fisheries

BIOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVES ON CRAB MANAGEMENT IN ALASKA: AN ORAL REPORT TO THE ALASKA BOARD OF FISHERIES BY Gordon H. Kruse Regional Information Report No. 5593-02 Alaska Department of Fish & Game Division of Commercial Fisheries P.O. Box 25526 Juneau, Alaska 99802-5526 January 31, 1993 BIOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVES ON CRAB MANAGEMENT IN ALASKA: AN ORAL REPORT TO THE ALASKA BOARD OF FISHERIES BY Gordon H. Kruse Regional Information ~eportlNo. 5J93-02 Alaska Department of Fish & Game Division of Commercial Fisheries P.O. Box 25526 Juneau., Alaska 99802-5526 January 31, 1993 l~heRegional Information Report Series was established in 1987 to provide an in£ormat ion access system for all unpublished divisional reports. These reports frequently serve diverse ad hoc informational purposes or archive basic uninterpreted data. To accommodate timely reporting of recently collected information, reports in this series undergo only limited internal review and may contain preliminary data; this information may be subsequently finalized and published in the formal literature. Consequently, these reports should not be cited without prior approval of the author or the Division of Commercial Fisheries. FORWARD We thought that we would begin the Board meeting with an overview of biology and management of crabs in Alaska. This talk is similar to a presentation that I have given at a couple of recent scientific meetings. One meeting was the International Symposium on Management Strategies for Exploited Fish Populations in Anchorage during October 21-24, 1992, and the other was the annual meeting of the Alaska Chapter of the American Fisheries Society in Valdez, Alaska, during November 16-19, 1992. -

Growth of Juvenile Golden King Crabs Lithodes Aequispinus in the Laboratory

Growth of Juvenile Golden King Crabs in the Laboratory • Paul and Paul 133 Growth of Juvenile Golden King Crabs Lithodes aequispinus in the Laboratory A. J. Paul and J. M. Paul Reprinted from the Alaska Fishery Research Bulletin Vol. 8 No. 2, Winter 2001 The Alaska Fisheries Research Bulletin can be found on the World Wide Web at URL: http://www.state.ak.us/adfg/geninfo/pubs/afrb/afrbhome.htm GrowthAlaska Fishery of Juvenile Research Golden Bulletin King 8(2) Crabs 135–138. in the 2001.Laboratory • Paul and Paul Notes135 Copyright © 2001 by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game Growth of Juvenile Golden King Crabs Lithodes aequispinus in the Laboratory A. J. Paul and J. M. Paul ABSTRACT: Growth observations were made for juvenile male golden king crabs Lithodes aequispinus with carapace lengths (CL) of 2 to 35 mm to improve our understanding of the recruitment process. Gravid females were captured in Prince William Sound, Alaska, and juveniles were reared in the laboratory at 3°–10°C to obtain information on growth per molt and intermolt duration. The equation describing the increase in CL for crabs 2 to 35 mm CL was: New CL mm = Initial CL (1.25) + 0.14; r2 = 0.99, n = 76. The average increase in CL after molting was 28% (SD = 8%), and the corresponding value for chela height (CH) was 33% (SD = 17%). The intermolt duration, in units of degree days, of crabs 2 to 35 mm CL was described by the equation: Intermolt Duration = Initial CL mm (16.32) + 259; r2 = 0.76. -

Challenging the Cold: Crabs Reconquer the Antarctic

Ecology, 86(3), 2005, pp. 619±625 q 2005 by the Ecological Society of America CHALLENGING THE COLD: CRABS RECONQUER THE ANTARCTIC SVEN THATJE,1,5 KLAUS ANGER,2 JAVIER A. CALCAGNO,3 GUSTAVO A. LOVRICH,4 HANS-OTTO POÈ RTNER,1 AND WOLF E. ARNTZ1 1Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research, Columbusstr. D-27568 Bremerhaven, Germany 2Biologische Anstalt Helgoland, Foundation Alfred Wegener Institute, Helgoland, Germany 3Universidad de Buenos Aires, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Intendente GuÈiraldes 2160, C1428EHA, Buenos Aires, Argentina 4Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Cientõ®cas y TeÂcnicas, Centro Austral de Investigaciones Cientõ®cas, CC 92, V9410BFD Ushuaia, Tierra del Fuego, Argentina Abstract. Recent records of lithodid crabs in deeper waters off the Antarctic continental slope raised the question of the return of crabs to Antarctic waters, following their extinction in the lower Miocene ;15 million years ago. Antarctic cooling may be responsible for the impoverishment of the marine high Antarctic decapod fauna, presently comprising only ®ve benthic shrimp species. Effects of polar conditions on marine life, including lowered metabolic rates and short seasonal food availability, are discussed as main evolutionary driving forces shaping Antarctic diversity. In particular, planktotrophic larval stages should be vulnerable to the mismatch of prolonged development and short periods of food avail- ability, selecting against complex life cycles. We hypothesize that larval lecithotrophy and cold tolerance, as recently observed in Subantarctic lithodids, represent, together with other adaptations in the adults, key features among the life-history adaptations of lithodids, potentially enabling them to conquer polar ecosystems. The return of benthic top predators to high Antarctic waters under conditions of climate change would considerably alter the benthic communities. -

A Review of Worldwide Fisheries for Lithodid Crabs (Decapoda: Anomura: Lithodidae) and Their Fluctuations

Bi ology ofAnomura II (A .Asakura ,e d.),Cr ustaceanR esearc h,Sp ec ialN umber6: 167-185,2006 A review of worldwide fisheries for lithodid crabs (Decapoda: Anomura: Lithodidae) and their fluctuations R obert S. Otto Abstra ct.-Lithodid crab fi sheries began species within these genera,trends in landings before1900 in Japan and spread across the and cu汀 ent status of major stocks contributing North Pacific Ocean by1940. Fisheries targeted to the world lithodid landings. lncidental or red kin gcrab (Paralithodes ca mtsc hati cus) with experimental fisheries for Neolithodes spp. and lesser amounts of blue king crab (P. platypus) for Lopholithodes spp. are omitt ed,because and brown king crab (P. brevip es) .Paralithod es documented landings are sporadic,trends spp.,es pec iall yred kin gcrabs ,h ave always are not evident and magnitudes negligible. dominated lithodid fisherie s. Golden king crab Likewise,1 have excluded recreational or (Lithodes aequispinus) becam eimportant in personal use fisheries,because statistics are North Pacific Ocean waters after major decline s frequently incomplete and known landings are in red king crab fisheries in the early 1980's. Southern kin gcrab (Lithodes sa ntolla) are fished generall ysm a ll relative to commercial白sheries. in so uthern South America along with softshell red crab (Paralomis granulosa). These five species DATASOURCES accounted for more than 89% of lithodid landings for 1984・2003. World lithodid landings pea ked at 1use United Nations Food and Agricultural 150,100 metric tons (t) in 1966 after development Organization (FAO) landing statistic sas a in pre-World War 11 Asia and rapid post-1950 starting point and more detai led publications ex pansion in A laskaand Asia. -

Spatial Variability in Size at Maturity and Reproductive Timing of Golden King Crab (Lithodes Aequispinus) in Southeast Alaska

Spatial variability in size at maturity and reproductive timing of golden king crab (Lithodes aequispinus) in Southeast Alaska Item Type Thesis Authors Olson, Andrew P. Download date 01/10/2021 23:44:12 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/6849 SPATIAL VARIABILITY IN SIZE AT MATURITY AND REPRODUCTIVE TIMING OF GOLDEN KING CRAB (LITHODESAEQUISPINUS) IN SOUTHEAST ALASKA By Andrew P. Olson, B.S. A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Fisheries University of Alaska Fairbanks August 2016 APPROVED: Dr. Ginny L. Eckert, Committee Chair Dr. Gordon H. Kruse, Committee Member Dr. Christopher E. Siddon, Committee Member Dr. Franz Mueter, Chair Graduate Program in Fisheries Dr. S. Bradley Moran, Dean School of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences Dr. Michael Castellini, Dean of the Graduate School Abstract Many crab fisheries around the world are managed by size, sex and season regulations, where male crabs are given at least one opportunity to reproduce before being harvested. Therefore, to set minimum legal size and fishing season for harvest, information on size at maturity and reproductive timing is needed. Lithodes aequispinus has supported a commercial fishery in Southeast Alaska since 1972, with an average annual harvest of 207 t. The current legal size and season for harvest are based L. aequispinus growth and maturity information from other parts of the range and limited information on reproduction. Additionally, evidence suggests that these life history parameters can vary spatially. Therefore, I investigated size at maturity, reproductive timing, and variation in harvest from the commercial fishery for L. -

(Lithodes Aequispinus) in the Ment Has Emerged with the Recent Adop- Eastern Aleutian Islands in Alaska Tion of a Size-Based Stock Assessment Model

380 National Marine Fisheries Service Fishery Bulletin First U.S. Commissioner established in 1881 of Fisheries and founder NOAA of Fishery Bulletin Abstract—The golden king crab (Lith- Development of harvest control rules for odes aequispinus) has traditionally been managed in the Aleutian Islands hard-to-age crab stocks: the example of the by using a constant catch strategy but interest in abundance- based manage- golden king crab (Lithodes aequispinus) in the ment has emerged with the recent adop- eastern Aleutian Islands in Alaska tion of a size-based stock assessment model. Management strategy evalua- 1 4 tion (MSE) is commonly used to quantify Shareef M. Siddeek (contact author) Steve Martell 2 1 conservation and economic trade-offs of Benjamin Daly Jie Zheng alternative management strategies, but André E. Punt3 Mark Stichert2 computational constraints can impede the representation of all sources of Email address for contact author: [email protected] uncertainty. We conducted a simpli- fied MSE for the golden king crab that 1 3 focused on what we regarded as the Division of Commercial Fisheries School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences major uncertainties, including initial Alaska Department of Fish and Game University of Washington stock abundance, future recruitment, P.O. Box 115526 P.O. Box 355020 estimation of mature male biomass Juneau, Alaska 99811 Seattle, Washington 98105- 5020 and abundance, and catch implementa- 2 Division of Commercial Fisheries 4 Sea State Inc. tion error, while capturing the existing Alaska Department of Fish and Game 9401 NE Tidal Court unique federal and state cooperative 351 Research Court Bainbridge Island, Washington 98110 management framework for crab stocks Kodiak, Alaska 99615 in the Bering Sea and Aleutian Islands. -

Growth of Juvenile Golden King Crabs Lithodes Aequispinus in the Laboratory

Growth of Juvenile Golden King Crabs in the Laboratory • Paul and Paul 133 Growth of Juvenile Golden King Crabs Lithodes aequispinus in the Laboratory A. J. Paul and J. M. Paul Reprinted from the Alaska Fishery Research Bulletin Vol. 8 No. 2, Winter 2001 The Alaska Fisheries Research Bulletin can be found on the World Wide Web at URL: http://www.state.ak.us/adfg/geninfo/pubs/afrb/afrbhome.htm 134 Notes GrowthAlaska Fishery of Juvenile Research Golden Bulletin King 8(2) Crabs 135–138. in the 2001.Laboratory • Paul and Paul Notes135 Copyright © 2001 by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game Growth of Juvenile Golden King Crabs Lithodes aequispinus in the Laboratory A. J. Paul and J. M. Paul ABSTRACT: Growth observations were made for juvenile male golden king crabs Lithodes aequispinus with carapace lengths (CL) of 2 to 35 mm to improve our understanding of the recruitment process. Gravid females were captured in Prince William Sound, Alaska, and juveniles were reared in the laboratory at 3°–10°C to obtain information on growth per molt and intermolt duration. The equation describing the increase in CL for crabs 2 to 35 mm CL was: New CL mm = Initial CL (1.25) + 0.14; r2 = 0.99, n = 76. The average increase in CL after molting was 28% (SD = 8%), and the corresponding value for chela height (CH) was 33% (SD = 17%). The intermolt duration, in units of degree days, of crabs 2 to 35 mm CL was described by the equation: Intermolt Duration = Initial CL mm (16.32) + 259; r2 = 0.76. -

Two New Cryptic and Sympatric Species of the King Crab Parasite Briarosaccus (Cirripedia: Rhizocephala) in the North Pacific

Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2016, 176, 3–14. With 5 figures Two new cryptic and sympatric species of the king crab parasite Briarosaccus (Cirripedia: Rhizocephala) in the North Pacific CHRISTOPH NOEVER1*, ANDREW OLSON2 and HENRIK GLENNER1,3 1Marine Biodiversity Group, Department of Biology, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway 2Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Juneau, AK, USA 3CMEC, Natural History Museum, University of Copenhagen, Denmark Received 20 February 2015; revised 1 June 2015; accepted for publication 10 June 2015 Rhizocephalan barnacles have been reported to parasitize a wide range of king crab species (Lithodidae). So far all these parasites have been assigned to a single species, Briarosaccus callosus Boschma, 1930, which is assumed to have a global distribution. Here we investigate Briarosaccus specimens from three different king crab hosts from the fjord systems of Southeastern Alaska: Lithodes aequispinus Benedict, 1895, Paralithodes camtschaticus (Tilesius, 1815), and Paralithodes platypus (Brandt, 1850). Using molecular markers and by morphological com- parison we show that Briarosaccus specimens from these three commercial exploited king crabs are in fact mor- phologically distinct from B. callosus, and further represent two separate species which we describe. The two new species, Briarosaccus auratum n. sp. and B. regalis n. sp., are cryptic by morphological means and were identi- fied as distinct species by the use of genetic markers (COI and 16S). They occur sympatrically, yet no overlap in king crab hosts occurs, with B. auratum n. sp. only found on L. aequispinus, and B. regalis n. sp. as parasite of the two Paralithodes hosts. © 2016 The Authors. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd on behalf of The Linnean Society of London, Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2016 doi: 10.1111/zoj.12304 ADDITIONAL KEYWORDS: COI – cryptic speciation – DNA – Lithodidae – parasites – species delimita- tion – sympatric occurrence – 16S. -

Industrial Fisheries in the Russian Part of the Bering Sea

TRAWLING IN THE MIST: INDUSTRIAL FISHERIES IN THE RUSSIAN PART OF THE BERING SEA by Alexey Vaisman Funding for the production of this report was kindly provided by WWF-US and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation : Vaisman, Alexey TRAFFIC Europe-Russia Credit Fish in the hold of a trawler impounded in the Russian part of the Bering Sea TRAWLING IN THE MIST: INDUSTRIAL FISHERIES IN THE RUSSIAN PART OF THE BERING SEA TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements iii Executive Summary iv Background 1 Introduction 3 Methodology 4 History of industrial fisheries in the Russian part of the Bering Sea 6 Overview of the fishery in the 1990s 7 Structure of fisheries administration 10 Fisheries legislation and agreements 10 Management of the fishery 14 Stocks and quotas 14 Enforcement of fisheries legislation 17 Recorded catches in the Russian part of the Bering Sea 19 Fishing gears used in the Bering Sea 21 The fishery species-by-species 23 Alaska Pollack 23 Crabs 28 Cods 32 Pacific Herring 37 Rockfishes 39 Halibuts and flounders 42 Yellowfin Sole and other plaices 44 Shrimps 47 Commander Squid 48 Exports of fisheries products reported from Kamchatka 49 Fisheries violations in the Russian Far East, with specific reference to the Bering Sea 52 Types of violation 55 Factors contributing to illegal activities 62 Inappropriate legislation 62 Weaknesses in the enforcement system 64 Organized crime 66 Conclusions and recommendations 67 References 76 Annex 1: Institutions and terminology associated with Bering Sea fisheries, in English and Russian Annex 2: Reported catches of major industrial fisheries in the North Pacific ii TRAWLING IN THE MIST: INDUSTRIAL FISHERIES IN THE RUSSIAN PART OF THE BERING SEA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The kind support of WWF-US allowed this report, and the investigations on which it is based, to be translated into reality. -

Case Study on Russian King Crab Sourcing and Traceability Pilot

Case Study on Russian King Crab Sourcing and Traceability Pilot 2019 2 CASE STUDY ON RUSSIAN KING CRAB SOURCING AND TRACEABILITY PILOT CASE STUDY ON RUSSIAN KING CRAB SOURCING AND TRACEABILITY PILOT 1 Contents Preface ........................................................................................ 2 Acknowledgments ..................................................................... 2 Disclaimer ................................................................................... 3 I. Introduction ............................................................................. 4 II. Due Care and Risk Mitigation Sourcing Guidance ............ 13 Map ........................................................................................... 20 III. Traceability Pilot and Verification Mechanisms .............. 22 IV. Eye to the Future ................................................................ 29 Endnotes ................................................................................... 31 Appendix 1: Summary of Traceability Pilot Mechanisms, by Key Data Element (KDE) ..................................................... 34 Appendix 2: Description of Inputs and Outputs for AIS Verification Using Global Fishing Watch ............................... 35 CITATION WWF. 2019. Case Study on Russian King Crab Sourcing and Traceability Pilot. Washington, D.C. Fishers retrieving a crab trap and sorting the catch prior to on-board processing. © Sergey Korostelev / WWF Russia 2 CASE STUDY ON RUSSIAN KING CRAB SOURCING AND TRACEABILITY PILOT -

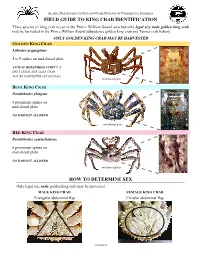

Prince William Sound Field Guide to King Crab Identification

ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME DIVISION OF COMMERCIAL FISHERIES FIELD GUIDE TO KING CRAB IDENTIFICATION Three species of king crab occur in the Prince William Sound area but only legal size male golden king crab may be harvested in the Prince William Sound subsistence golden king crab and Tanner crab fishery. ONLY GOLDEN KING CRAB MAY BE HARVESTED GOLDEN KING CRAB Lithodes aequispinus mid-dorsal plate 5 to 9 spines on mid-dorsal plate ANNUAL HOUSEHOLD LIMIT = 3 ONLY LEGAL SIZE MALE CRAB MAY BE HARVESTED (SEE REVERSE) mid-dorsal plate BLUE KING CRAB Paralithodes platypus mid-dorsal plate 4 prominent spines on mid-dorsal plate NO HARVEST ALLOWED mid-dorsal plate RED KING CRAB Paralithodes camtschaticus mid-dorsal plate 6 prominent spines on mid-dorsal plate NO HARVEST ALLOWED mid-dorsal plate HOW TO DETERMINE SEX Only legal size male golden king crab may be harvested. MALE KING CRAB FEMALE KING CRAB Triangular abdominal flap Circular abdominal flap -continued- ALASKA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND GAME DIVISION OF COMMERCIAL FISHERIES GOLDEN KING CRAB IDENTIFICATION Side view of rostrum Dorsal view of rostrum Paired tip HOW TO DETERMINE SIZE Legal male golden king crab carapace width is 7 inches or larger and is measured as the greatest straight line distance across the carapace including spines. Rostrum – look for paired tip Legal minimum size is 7 inches 5 to 9 spines on mid-dorsal plate More king crab information can be found in Biological Field Techniques for Lithodid Crabs by William E. Donaldson and Susan C. Byersdorfer, Alaska Sea Grant College Program, University of Alaska 2005.