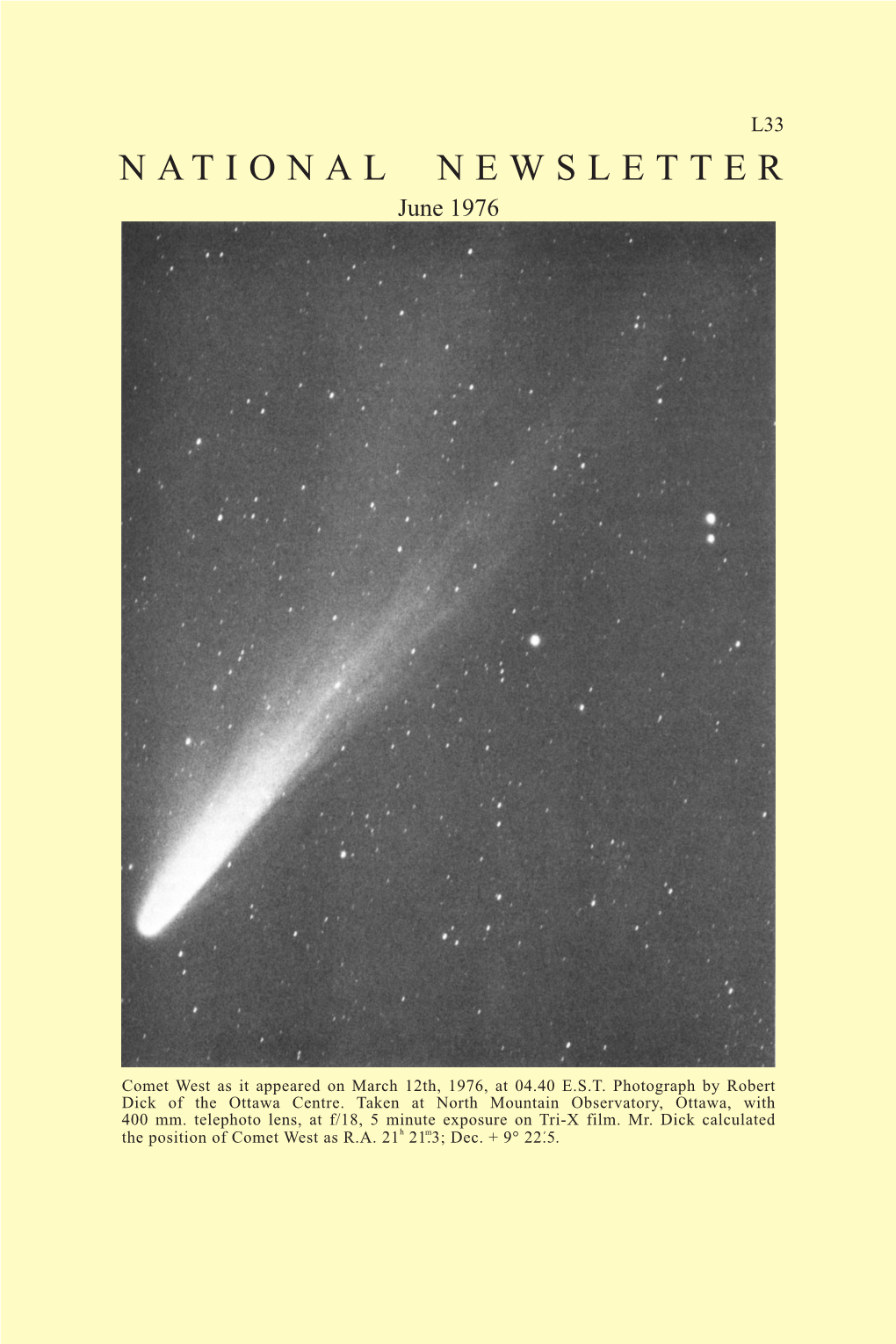

N a T I O N a L N E W S L E T T E R June 1976

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thinking Outside the Sphere Views of the Stars from Aristotle to Herschel Thinking Outside the Sphere

Thinking Outside the Sphere Views of the Stars from Aristotle to Herschel Thinking Outside the Sphere A Constellation of Rare Books from the History of Science Collection The exhibition was made possible by generous support from Mr. & Mrs. James B. Hebenstreit and Mrs. Lathrop M. Gates. CATALOG OF THE EXHIBITION Linda Hall Library Linda Hall Library of Science, Engineering and Technology Cynthia J. Rogers, Curator 5109 Cherry Street Kansas City MO 64110 1 Thinking Outside the Sphere is held in copyright by the Linda Hall Library, 2010, and any reproduction of text or images requires permission. The Linda Hall Library is an independently funded library devoted to science, engineering and technology which is used extensively by The exhibition opened at the Linda Hall Library April 22 and closed companies, academic institutions and individuals throughout the world. September 18, 2010. The Library was established by the wills of Herbert and Linda Hall and opened in 1946. It is located on a 14 acre arboretum in Kansas City, Missouri, the site of the former home of Herbert and Linda Hall. Sources of images on preliminary pages: Page 1, cover left: Peter Apian. Cosmographia, 1550. We invite you to visit the Library or our website at www.lindahlll.org. Page 1, right: Camille Flammarion. L'atmosphère météorologie populaire, 1888. Page 3, Table of contents: Leonhard Euler. Theoria motuum planetarum et cometarum, 1744. 2 Table of Contents Introduction Section1 The Ancient Universe Section2 The Enduring Earth-Centered System Section3 The Sun Takes -

About the Foroughi Cup and About the Seven Planets in the Ancient World

Archaeoastronomy and Ancient Technologies 2018, 6(2), 31–37; http://aaatec.org/art/a_cm2 www.aaatec.org ISSN 2310-2144 About the Foroughi Cup and about the seven planets in the Ancient World Mario Codebò 1, Henry De Santis 2 1 Archeoastronomia Ligustica, S.I.A., SAIt, Genoa, Italy; E-Mail: [email protected] 2 Archeoastronomia Ligustica, S.I.A., SAIt, Genoa, Italy; E-Mail: [email protected] Abstract The Foroughi Cup is an artefact of the 8th century BC of Aramaic cultural context, inside which images of stars and constellations are reproduced. In this study of ours we start from the conclusions reached by Amadasi Guzzo and Castellani in their two works of 2005 and 2006 and we add some further considerations and identifications. We then explain the hypothesis that some cultures of the Ancient World include seven planets, excluding the Moon and the Sun, because Mercury and Venus, always visible only at dawn or at sunset, were perhaps considered four different planets. Finally, we propose the thesis that their evil character depends, as for every new star (novae, supernovae, comets, etc.), on the fact that they alter the synchrony of the cosmos with their variable motion (variable declination heaven bodies). Keywords: Foroughi Cup, planets, Moon, Sun, Aramaic culture. The Foroughi Cup The Foroughi Cup is a bronze artefact (fig. 1), dated to the first half of the 1st millennium BC, containing in its concave interior a representation of the celestial vault and seven very small Aramaic inscriptions, only three of which are quite legible: ŠMŠ = Sun (above the representation of the Sun, in which a lion's head is also engraved); ŠHR = Moon (above the representation of the crescent of the Moon); hypothetically R'Š ŠR' = Head of the Bull (above the bucranium). -

Gaia Data Release 2 Special Issue

A&A 623, A110 (2019) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201833304 & © ESO 2019 Astrophysics Gaia Data Release 2 Special issue Gaia Data Release 2 Variable stars in the colour-absolute magnitude diagram?,?? Gaia Collaboration, L. Eyer1, L. Rimoldini2, M. Audard1, R. I. Anderson3,1, K. Nienartowicz2, F. Glass1, O. Marchal4, M. Grenon1, N. Mowlavi1, B. Holl1, G. Clementini5, C. Aerts6,7, T. Mazeh8, D. W. Evans9, L. Szabados10, A. G. A. Brown11, A. Vallenari12, T. Prusti13, J. H. J. de Bruijne13, C. Babusiaux4,14, C. A. L. Bailer-Jones15, M. Biermann16, F. Jansen17, C. Jordi18, S. A. Klioner19, U. Lammers20, L. Lindegren21, X. Luri18, F. Mignard22, C. Panem23, D. Pourbaix24,25, S. Randich26, P. Sartoretti4, H. I. Siddiqui27, C. Soubiran28, F. van Leeuwen9, N. A. Walton9, F. Arenou4, U. Bastian16, M. Cropper29, R. Drimmel30, D. Katz4, M. G. Lattanzi30, J. Bakker20, C. Cacciari5, J. Castañeda18, L. Chaoul23, N. Cheek31, F. De Angeli9, C. Fabricius18, R. Guerra20, E. Masana18, R. Messineo32, P. Panuzzo4, J. Portell18, M. Riello9, G. M. Seabroke29, P. Tanga22, F. Thévenin22, G. Gracia-Abril33,16, G. Comoretto27, M. Garcia-Reinaldos20, D. Teyssier27, M. Altmann16,34, R. Andrae15, I. Bellas-Velidis35, K. Benson29, J. Berthier36, R. Blomme37, P. Burgess9, G. Busso9, B. Carry22,36, A. Cellino30, M. Clotet18, O. Creevey22, M. Davidson38, J. De Ridder6, L. Delchambre39, A. Dell’Oro26, C. Ducourant28, J. Fernández-Hernández40, M. Fouesneau15, Y. Frémat37, L. Galluccio22, M. García-Torres41, J. González-Núñez31,42, J. J. González-Vidal18, E. Gosset39,25, L. P. Guy2,43, J.-L. Halbwachs44, N. C. Hambly38, D. -

Download This Issue (Pdf)

Volume 46 Number 1 JAAVSO 2018 The Journal of the American Association of Variable Star Observers Optical Flares and Quasi-Periodic Pulsations on CR Draconis during Periastron Passage Upper panel: 2017-10-10-flare photon counts, time aligned with FFT spectrogram. Lower panel: FFT spectrogram shows time in UT seconds versus QPP periods in seconds. Flares cited by Doyle et al. (2018) are shown with (*). Also in this issue... • The Dwarf Nova SY Cancri and its Environs • KIC 8462852: Maria Mitchell Observatory Photographic Photometry 1922 to 1991 • Visual Times of Maxima for Short Period Pulsating Stars III • Recent Maxima of 86 Short Period Pulsating Stars Complete table of contents inside... The American Association of Variable Star Observers 49 Bay State Road, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA The Journal of the American Association of Variable Star Observers Editor John R. Percy Kosmas Gazeas Kristine Larsen Dunlap Institute of Astronomy University of Athens Department of Geological Sciences, and Astrophysics Athens, Greece Central Connecticut State University, and University of Toronto New Britain, Connecticut Toronto, Ontario, Canada Edward F. Guinan Villanova University Vanessa McBride Associate Editor Villanova, Pennsylvania IAU Office of Astronomy for Development; Elizabeth O. Waagen South African Astronomical Observatory; John B. Hearnshaw and University of Cape Town, South Africa Production Editor University of Canterbury Michael Saladyga Christchurch, New Zealand Ulisse Munari INAF/Astronomical Observatory Laszlo L. Kiss of Padua Editorial Board Konkoly Observatory Asiago, Italy Geoffrey C. Clayton Budapest, Hungary Louisiana State University Nikolaus Vogt Baton Rouge, Louisiana Katrien Kolenberg Universidad de Valparaiso Universities of Antwerp Valparaiso, Chile Zhibin Dai and of Leuven, Belgium Yunnan Observatories and Harvard-Smithsonian Center David B. -

Planetquest Outreach Toolkit Manual and Resources Cd

Outreach ToolKit Manual DISTRIBUTED FOR MEMBERS OF THE NASA NIGHT SKY NETWORK THE NIGHT SKY NETWORK IS SPONSORED AND SUPPORTED BY JPL'S PLANETQUEST PUBLIC ENGAGEMENT PROGRAM. PLANETQUEST IS A PART OF JPL’S NAVIGATOR PROGRAM, WHICH ENCOMPASSES SEVERAL OF NASA'S EXTRA-SOLAR PLANET- FINDING MISSIONS, INCLUDING THE KECK INTERFEROMETER, THE SPACE INTERFEROMETRY MISSION (SIM), THE TERRESTRIAL PLANET FINDER (TPF), THE LARGE BINOCULAR TELESCOPE INTERFEROMETER (LBTI), AND THE MICHELSON SCIENCE CENTER. NASA NIGHT SKY NETWORK: http://nightsky.jpl.nasa.gov/ PLANETQUEST: http://planetquest.jpl.nasa.gov/ Contacts The non-profit Astronomical Society of the Pacific (ASP), one of the nation’s leading organizations devoted to astronomy and space science education, is managing the Night Sky Network in cooperation with JPL. Learn more about the ASP at http://www.astrosociety.org. For support contact: Astronomical Society of the Pacific (ASP) 390 Ashton Avenue San Francisco, CA 94112 415-337-1100 ext. 116 [email protected] Copyright © 2004 NASA/JPL and Astronomical Society of the Pacific. Copies of this manual and documents may be made for educational and public outreach purposes only and are to be supplied at no charge to participants. Any other use is not permitted. CREDITS: All photos and images in the ToolKit Manual unless otherwise noted are provided courtesy of Marni Berendsen and Rich Berendsen. Your Club’s Membership in the NASA Night Sky Network Welcome to the NASA Night Sky Network! Your membership in the Night Sky Network will provide many opportunities for your club to expand its public education and outreach. Your club has at least two members who are the Night Sky Network Club Coordinators. -

CHROMOSPHERICALLY ACTIVE STARS. XXV. HD 144110 = EV DRACONIS, a DOUBLE-LINED DWARF BINARY Francis C

A The Astronomical Journal, 130:794–798, 2005 August # 2005. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in U.S.A. CHROMOSPHERICALLY ACTIVE STARS. XXV. HD 144110 = EV DRACONIS, A DOUBLE-LINED DWARF BINARY Francis C. Fekel,1,2 Gregory W. Henry,2 and Ceteka Lewis Center of Excellence in Information Systems, Tennessee State University, 330 10th Avenue North, Nashville, TN 37203; [email protected], [email protected] Received 2005 March 2; accepted 2005 April 21 ABSTRACT New spectroscopic and photometric observations of HD 144110 have been used to obtain an improved orbital element solution and determine some basic properties of the system. This chromospherically active, double-lined spectroscopic binary has an orbital period of 1.6714012 days and a circular orbit. We classify the components as G5 Vand K0 Vand suggest that they are slightly metal-rich. The photometric observations indicate that the rotation of HD 144110 is synchronous with the orbital period. Despite the short orbital period, no evidence of eclipses is seen in our photometry. Key words: binaries: spectroscopic — stars: late-type — stars: spots — stars: variables: other Online material: machine-readable table 1. INTRODUCTION tional Observatory (KPNO) coude´ feed telescope, coude´ spec- trograph, and a TI CCD detector. All of the spectrograms are In 1991, ROSAT with its Wide-Field Camera completed the 8 first all-sky survey of extreme ultraviolet (EUV) wavelengths. The centered in the red at 6430 , cover a wavelength range of about 80 8, and have a resolution of 0.21 8. Typical signal-to-noise satellite results led to follow-up optical observations from which ratios are 150–200. -

![Arxiv:1708.07700V3 [Physics.Ed-Ph] 31 Aug 2017 Zon to the South](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9974/arxiv-1708-07700v3-physics-ed-ph-31-aug-2017-zon-to-the-south-2709974.webp)

Arxiv:1708.07700V3 [Physics.Ed-Ph] 31 Aug 2017 Zon to the South

AstroEDU manuscript no. astroedu1645 c AstroEDU 2017 September 1, 2017 Navigation in the Ancient Mediterranean and Beyond M. Nielbock Haus der Astronomie, Campus MPIA, Königstuhl 17, D-69117 Heidelberg, Germany e-mail: [email protected] Received August 8, 2016; accepted March 2, 2017 ABSTRACT This lesson unit has been developed within the framework the EU Space Awareness project. It provides an insight into the history and navigational methods of the Bronze Age Mediterranean peoples. The students explore the link between exciting history and astronomical knowledge. Besides an overview of ancient seafaring in the Mediterranean, the students explore in two hands-on activities early navigational skills using the stars and constellations and their apparent nightly movement across the sky. In the course of the activities, they become familiar with the stellar constellations and how they are distributed across the northern and southern sky. Key words. navigation, astronomy, ancient history, Bronze Age, geography, stars, Polaris, North Star, latitude, meridian, pole height, circumpolar, celestial navigation, Mediterranean 1. Background information the celestial poles. Archaeological evidence from prehistoric eras like burials and the orientation of buildings demonstrates that the 1.1. Cardinal directions cardinal directions were common knowledge in a multitude of The cardinal directions are defined by astronomical processes cultures already many millennia ago. Therefore, it is obvious that like diurnal and annual apparent movements of the Sun and the they were applied to early navigation. The magnetic compass was apparent movements of the stars. In ancient and prehistoric times, unknown in Europe until the 13th century CE (Lane 1963). the sky certainly had a different significance than today. -

DISCOVERY and VALIDATION of Kepler-452B: a 1.6-R⊕ SUPER EARTH EXOPLANET in the HABITABLE ZONE of a G2 STAR Jon M

Received 2015 March 3; accepted 2015 May 23; published 2015 July 23 by the Astronomical Journal Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 12/16/11 DISCOVERY AND VALIDATION OF Kepler-452b: A 1:6-R⊕ SUPER EARTH EXOPLANET IN THE HABITABLE ZONE OF A G2 STAR Jon M. Jenkins1, Joseph D. Twicken1,2, Natalie M. Batalha1, Douglas A. Caldwell1,2, William D. Cochran3, Michael Endl3, David W. Latham4, Gilbert A. Esquerdo4, Shawn Seader1,2, Allyson Bieryla4, Erik Petigura5, David R. Ciardi6, Geoffrey W. Marcy5, Howard Isaacson5, Daniel Huber7,2,8, Jason F. Rowe1,2, Guillermo Torres4, Stephen T. Bryson1, Lars Buchhave4,9, Ivan Ramirez3, Angie Wolfgang10, Jie Li1,2, Jennifer R. Campbell11, Peter Tenenbaum1,2, Dwight Sanderfer1 Christopher E. Henze1, Joseph H. Catanzarite1,2, Ronald L. Gilliland12, and William J. Borucki1 Received 2015 March 3; accepted 2015 May 23; published 2015 July 23 by the Astronomical Journal ABSTRACT We report on the discovery and validation of Kepler-452b, a transiting planet identified by a search +0:23 through the 4 years of data collected by NASA's Kepler Mission. This possibly rocky 1:63−0:20-R⊕ +0:007 planet orbits its G2 host star every 384:843−0:012 days, the longest orbital period for a small (RP < 2 R⊕) transiting exoplanet to date. The likelihood that this planet has a rocky composition lies between 49% and 62%. The star has an effective temperature of 5757 ± 85 K and a log g of 4:32 ± 0:09. At +0:019 a mean orbital separation of 1:046−0:015 AU, this small planet is well within the optimistic habitable zone of its star (recent Venus/early Mars), experiencing only 10% more flux than Earth receives from the Sun today, and slightly outside the conservative habitable zone (runaway greenhouse/maximum +0:15 greenhouse). -

Extrasolar Planets and Their Host Stars

Kaspar von Braun & Tabetha S. Boyajian Extrasolar Planets and Their Host Stars July 25, 2017 arXiv:1707.07405v1 [astro-ph.EP] 24 Jul 2017 Springer Preface In astronomy or indeed any collaborative environment, it pays to figure out with whom one can work well. From existing projects or simply conversations, research ideas appear, are developed, take shape, sometimes take a detour into some un- expected directions, often need to be refocused, are sometimes divided up and/or distributed among collaborators, and are (hopefully) published. After a number of these cycles repeat, something bigger may be born, all of which one then tries to simultaneously fit into one’s head for what feels like a challenging amount of time. That was certainly the case a long time ago when writing a PhD dissertation. Since then, there have been postdoctoral fellowships and appointments, permanent and adjunct positions, and former, current, and future collaborators. And yet, con- versations spawn research ideas, which take many different turns and may divide up into a multitude of approaches or related or perhaps unrelated subjects. Again, one had better figure out with whom one likes to work. And again, in the process of writing this Brief, one needs create something bigger by focusing the relevant pieces of work into one (hopefully) coherent manuscript. It is an honor, a privi- lege, an amazing experience, and simply a lot of fun to be and have been working with all the people who have had an influence on our work and thereby on this book. To quote the late and great Jim Croce: ”If you dig it, do it. -

![Arxiv:1204.3955V1 [Astro-Ph.EP] 18 Apr 2012 19 Bay Area Environmental Research Institute, Inc., 560 Third St](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0643/arxiv-1204-3955v1-astro-ph-ep-18-apr-2012-19-bay-area-environmental-research-institute-inc-560-third-st-3860643.webp)

Arxiv:1204.3955V1 [Astro-Ph.EP] 18 Apr 2012 19 Bay Area Environmental Research Institute, Inc., 560 Third St

The Transiting Circumbinary Planets Kepler-34 and Kepler-35 William F. Welsh1, Jerome A. Orosz1, Joshua A. Carter2, Daniel C. Fabrycky3, Eric B. Ford4, Jack J. Lissauer5, Andrej Prsa6, Samuel N. Quinn2,22, Darin Ragozzine2, Donald R. Short1, Guillermo Torres2, Joshua N. Winn7, Laurance R. Doyle8, Thomas Barclay5,19, Natalie Batalha5,20, Steven Bloemen23, Erik Brugamyer9, Lars A. Buchhave10,21, Caroline Caldwell9, Douglas A. Caldwell8, Jessie L. Christiansen5,8, David R. Ciardi11, William D. Cochran9, Michael Endl9, Jonathan J. Fortney12, Thomas N. Gautier III13, Ronald L. Gilliland25, Michael R. Haas5, Jennifer R. Hall24, Matthew J. Holman2, Andrew W. Howard14, Steve B. Howell5, Howard Isaacson14, Jon M. Jenkins5,8, Todd C. Klaus24, David W. Latham2, Jie Li5,8, Geoffrey W. Marcy14, Tsevi Mazeh15, Elisa V. Quintana5,8, Paul Robertson9, Avi Shporer16,18, Jason H. Steffen17, Gur Windmiller1, David G. Koch5, and William J. Borucki5 1Astronomy Department, San Diego State University, 5500 Campanile Dr. San Diego, CA 92182, USA 2Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA 3UCO/Lick Observatory, University of California, Santa Cruz, CA 95064, USA 4University of Florida, 211 Bryant Space Science Center, Gainesville, FL 32611-2055, USA 5NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, CA, 94035, USA 6Villanova Univ., Dept. of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 800 E Lancaster Ave, Villanova, PA 19085, USA 7Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Physics Department and Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research, 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA 8Carl Sagan Center for the Study of Life in the Universe, SETI Institute, 189 Bernardo Avenue, Mountain View, CA 94043, USA 9McDonald Observatory, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin TX 78712-0259, USA 10Niels Bohr Institute, Copenhagen University, Juliane Maries Vej 30, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark 11 NASA Exoplanet Science Institute/Caltech, 770 South Wilson Ave, Pasadena, CA USA 91125, USA 12Dept. -

Full Program

1 Schedule Abstracts Author Index 2 Schedule Schedule ............................................................................................................................... 3 Abstracts ............................................................................................................................... 5 Monday, September 12, 2011, 8:30 AM - 10:00 AM ................................................................................ 5 01: Overview of Observations and Welcome ....................................................................................... 5 Monday, September 12, 2011, 10:30 AM - 12:00 PM .............................................................................. 7 02: Radial Velocities ............................................................................................................................. 7 Monday, September 12, 2011, 2:00 PM - 3:30 PM ................................................................................ 10 03: Transiting Planets ......................................................................................................................... 10 Monday, September 12, 2011, 4:00 PM - 5:30 PM ................................................................................ 13 04: Transiting Planets II ...................................................................................................................... 13 Tuesday, September 13, 2011, 8:30 AM - 10:00 AM .............................................................................. 16 05: Planets -

The Planetary Nebula Club Objects by Month (As Posted by Ted Forte On

The Planetary Nebula Club objects by month (As posted by Ted Forte on “backbayastro”) August Planetaries As most of you know, I am the coordinator of the Astronomical League’s Planetary Nebula Club. Several members of the BBAA helped me create the Planetary Nebula Club by serving on the object selection committee, serving on the rules committee, providing images, or by authoring parts of the observing manual. The Planetary Nebula Club creation was truly a BBAA effort. I think it’s a shame, therefore, that more BBAA’ers haven’t completed the program and earned the pin. So if you are looking for an observing program to complete, why not our very own? There was never a better time to start. More than half the list is visible right now and no less than 31 of our 110 PNe are optimally placed in August. Hence the title of this epistle. It is my intention to spark an interest in the program and suggest the objects that might be bagged in the coming weeks. Many of you have no doubt observed these objects already, so please chime in and share your impressions of them. As is true of the entire list, our August selection contains both well-known showpieces and some seldom mentioned objects that you might not consider tracking down if not for this program. There are no less than 17 of the 31 August objects that I would describe as “stellar”. I must confess that I am not the biggest fan of these tiny objects and had I been the sole arbiter of the list it would have contained far fewer of these.