The Case of Trade in Hazardous Chemicals and Persistent Organic Pollutants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reference Guide

Indoor Air Quality Tools for Schools REFERENCE GUIDE Indoor Air Quality (IAQ) U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Indoor Environments Division, 6609J 1200 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20460 (202) 564-9370 www.epa.gov/iaq American Federation of Teachers 555 New Jersey Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20001 (202) 879-4400 www.aft.org Association of School Business Officials 11401 North Shore Drive Reston, VA 22090 (703) 478-0405 www.asbointl.org National Education Association 1201 16th Steet, NW Washington, DC 20036-3290 (202) 833-4000 www.nea.org National Parent Teachers Association 330 North Wabash Avenue, Suite 2100 Chicago, IL 60611-3690 (312) 670-6782 www.pta.org American Lung Association 1740 Broadway New York, NY 10019 (212) 315-8700 www.lungusa.org EPA 402/K-07/008 I January 2009 I www.epa.gov/iaq/schools Introduction � U nderstanding the importance of good basic measurement equipment, hiring indoor air quality (IAQ) in schools is the professional assistance, and codes and backbone of developing an effective IAQ regulations. There are numerous resources program. Poor IAQ can lead to a large available to schools through EPA and other variety of health problems and potentially organizations, many of which are listed in affect comfort, concentration, and staff/ Appendix L. Use the information in this student performance. In recognition of Guide to create the best possible learning tight school budgets, this guidance is environment for students and maintain a designed to present practical and often comfortable, healthy building for school low-cost actions you can take to identify occupants. and address existing or potential air quality Refer to A Framework for School problems. -

Chlorofluorocarbons Chem 300A Tyler Jensen, Mackenzie Latimer, Jessie Luther, Jake Mcghee, Adeeb Noorani, Tyla Penner, & Maddy Springle

Chlorofluorocarbons Chem 300a Tyler Jensen, Mackenzie Latimer, Jessie Luther, Jake McGhee, Adeeb Noorani, Tyla Penner, & Maddy Springle 1.1: A Brief History of Chlorofluorocarbons Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), also known as Freons, were first synthesized in 1928 by Thomas Midgley Jr, who was working for General Motors trying to find a safe refrigerant to use in commercial applications. (Rosenbaum, n.d.). They are an anthropogenic compound containing fluorine, carbon, and chlorine atoms, and are classified as halocarbons. CFCs are a family of chemicals based upon hydrocarbon skeletons, where most hydrogens have been replaced with chlorine and/or fluorine atoms. They are chemically stable freons that are non-flammable, tasteless and odourless. CFCs are very volatile, which makes for ideal refrigerant gases, having a boiling point close to zero degrees (Rosenbaum, n.d) They were originally created to replace the toxic gases used in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. Examples of the toxic gases replaced by CFCs as refrigerants are ammonia (NH3), methyl chloride (CH3Cl), and sulfur dioxide (SO2) (Wilkins, 1999). When first created dichlorodifloromethane was found to be less toxic than carbon dioxide, and as non-flammable as carbon tetrachloride (Midgley & Henne, 1930). The non-toxic, non-flammable, and non-reactive properties of CFCs made them ideal for use as refrigerants. CFCs were used in many developed countries for consumption and production as they were inflammable and non-toxic towards humanity. Chlorofluorocarbons can be used as refrigerants, cleaning agents, foaming agents, and propellants for aerosol sprays (Welch, n.d.). In 1974, Two University of California chemists, Professor F. Sherwood Rowland and Dr. -

Use of Chlorofluorocarbons in Hydrology : a Guidebook

USE OF CHLOROFLUOROCARBONS IN HYDROLOGY A Guidebook USE OF CHLOROFLUOROCARBONS IN HYDROLOGY A GUIDEBOOK 2005 Edition The following States are Members of the International Atomic Energy Agency: AFGHANISTAN GREECE PANAMA ALBANIA GUATEMALA PARAGUAY ALGERIA HAITI PERU ANGOLA HOLY SEE PHILIPPINES ARGENTINA HONDURAS POLAND ARMENIA HUNGARY PORTUGAL AUSTRALIA ICELAND QATAR AUSTRIA INDIA REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA AZERBAIJAN INDONESIA ROMANIA BANGLADESH IRAN, ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF RUSSIAN FEDERATION BELARUS IRAQ SAUDI ARABIA BELGIUM IRELAND SENEGAL BENIN ISRAEL SERBIA AND MONTENEGRO BOLIVIA ITALY SEYCHELLES BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA JAMAICA SIERRA LEONE BOTSWANA JAPAN BRAZIL JORDAN SINGAPORE BULGARIA KAZAKHSTAN SLOVAKIA BURKINA FASO KENYA SLOVENIA CAMEROON KOREA, REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA CANADA KUWAIT SPAIN CENTRAL AFRICAN KYRGYZSTAN SRI LANKA REPUBLIC LATVIA SUDAN CHAD LEBANON SWEDEN CHILE LIBERIA SWITZERLAND CHINA LIBYAN ARAB JAMAHIRIYA SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC COLOMBIA LIECHTENSTEIN TAJIKISTAN COSTA RICA LITHUANIA THAILAND CÔTE D’IVOIRE LUXEMBOURG THE FORMER YUGOSLAV CROATIA MADAGASCAR REPUBLIC OF MACEDONIA CUBA MALAYSIA TUNISIA CYPRUS MALI TURKEY CZECH REPUBLIC MALTA UGANDA DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC MARSHALL ISLANDS UKRAINE OF THE CONGO MAURITANIA UNITED ARAB EMIRATES DENMARK MAURITIUS UNITED KINGDOM OF DOMINICAN REPUBLIC MEXICO GREAT BRITAIN AND ECUADOR MONACO NORTHERN IRELAND EGYPT MONGOLIA UNITED REPUBLIC EL SALVADOR MOROCCO ERITREA MYANMAR OF TANZANIA ESTONIA NAMIBIA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ETHIOPIA NETHERLANDS URUGUAY FINLAND NEW ZEALAND UZBEKISTAN FRANCE NICARAGUA VENEZUELA GABON NIGER VIETNAM GEORGIA NIGERIA YEMEN GERMANY NORWAY ZAMBIA GHANA PAKISTAN ZIMBABWE The Agency’s Statute was approved on 23 October 1956 by the Conference on the Statute of the IAEA held at United Nations Headquarters, New York; it entered into force on 29 July 1957. The Headquarters of the Agency are situated in Vienna. -

Applied and Fundamental Heterogeneous Catalysis Studies

APPLIED AND FUNDAMENTAL HETEROGENEOUS CATALYSIS STUDIES ON HYDRODECHLORINATION OF TRICHLOROETHYLENE AND STEAM REFORMING OF ETHANOL DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Hyuntae Sohn, M.S. Graduate Program in Chemical Engineering The Ohio State University 2016 - Dissertation Committee - Prof. Umit S. Ozkan, Advisor Prof. Andre Palmer Prof. Lisa Hall Prof. T.V. (Babu) RajanBabu Copyright by Hyuntae Sohn 2016 ABSTRACT The dissertation herein reports heterogeneous catalysis studies conducted on two different projects, (1) Hydrodechlorination of trichloroethylene and (2) Ethanol steam reforming. The former is associated with the process for trichloroethylene waste treatment and groundwater remediation technology whereas the latter pertains to hydrogen production. The presented work involves not only investigations on the catalytic activity, but also fundamental studies to understand how and why a catalyst works for a particular reaction. This dissertation is composed of two major parts. (1) Part I (Chapter 1-4): Trichloroethylene (TCE) is a chlorinated hydrocarbon solvent which has been widely used as a vapor degreaser for metal cleaning. TCE contains high level of toxicity, also known as a carcinogen. Recently, contamination of groundwater due to untreated TCE is a rapidly rising environmental issue, affecting the drinking water quality. The current waste treatment process for removal of TCE are mostly based on adsorption and extraction techniques. However, these processes do not provide a complete destruction of the TCE chemical structure; hence, it requires an additional incinerator to convert TCE into non harmful products. Hydrodechlorination (HDC) of TCE is a catalytic chemical reaction where TCE is converted to ethane and hydrochloric acid using hydrogen as a reducing agent. -

THOMAS MIDGLEY, JR., and the INVENTION of CHLOROFLUOROCARBON REFRIGERANTS: IT AIN’T NECESSARILY SO Carmen J

66 Bull. Hist. Chem., VOLUME 31, Number 2 (2006) THOMAS MIDGLEY, JR., AND THE INVENTION OF CHLOROFLUOROCARBON REFRIGERANTS: IT AIN’T NECESSARILY SO Carmen J. Giunta, Le Moyne College The 75th anniversary of the first public Critical readers are well aware description of chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) of the importance of evaluating refrigerants was observed in 2005. A sources of information. For ex- symposium at a national meeting of ample, an article in Nature at the the American Chemical Society (ACS) end of 2005 tested the accuracy on CFCs from invention to phase-out of two encyclopedias’ entries on a (1) and an article on their invention sample of topics about science and and inventor in the Chemical Educa- history of science (3). A thought- tor (2) marked the occasion. The story ful commentary published soon of CFCs—their obscure early days as afterwards raised questions on just laboratory curiosities, their commercial what should count as an error in debut as refrigerants, their expansion into assessing such articles: omissions? other applications, and the much later disagreements among generally re- discovery of their deleterious effects on liable sources (4)? Readers of his- stratospheric ozone—is a fascinating torical narratives who are neither one of science and society well worth practicing historians nor scholarly telling. That is not the purpose of this amateurs (the category to which I article, though. aspire) may find an account of a Thomas Midgley, Jr. historical research process attrac- This paper is about contradictory Courtesy Richard P. Scharchburg tive. As a starting point, consider sources, foggy memories, the propaga- Archives, Kettering University the following thumbnail summary tion of error, and other obstacles to writ- of the invention. -

Overview of Fluorocarbons

Three Bond Technical News Issued Dec. 20, 1989 An Overview of Fluorocarbons Introduction Currently, chlorofluorocarbons are garnering a lot of Three Bond Co,. Ltd. has been working night and day in attention around the world. Chlorofluorocarbons are used in search of alternatives to chlorofluorocarbons. In the future, many of our products and when we look at the future of products that do not contain any chlorofluorocarbons will chlorofluorocarbons in the world, and in Japan, we can replace products that now contain chlorofluorocarbons. To foresee that their use will be strictly limited or eliminated all ensure these products reach our customers as smoothly as together. possible, it is important that they have a good understanding of the issues surrounding chlorofluorocarbons. Whatever the case, Three Bond Co., Ltd. is obligated to provide our customers with products that have the same functionality as chlorofluorocarbons. Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................1 1. What is a fluorocarbon? .......................................................................................................................................2 2. Properties of fluorocarbons ..................................................................................................................................2 3. Types of fluorocarbons.........................................................................................................................................2 -

Chlorofluorocarbon and Its Effects on the Ozone Layer: Is Legislation Sufficient to Protect the Environment Glenn M

North Carolina Central Law Review Volume 19 Article 8 Number 1 Volume 19, Number 1 10-1-1990 Chlorofluorocarbon and Its Effects on the Ozone Layer: Is Legislation Sufficient to Protect the Environment Glenn M. Mattei Follow this and additional works at: https://archives.law.nccu.edu/ncclr Part of the Environmental Law Commons Recommended Citation Mattei, Glenn M. (1990) "Chlorofluorocarbon and Its Effects on the Ozone Layer: Is Legislation Sufficient to Protect the Environment," North Carolina Central Law Review: Vol. 19 : No. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://archives.law.nccu.edu/ncclr/vol19/iss1/8 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by History and Scholarship Digital Archives. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Central Law Review by an authorized editor of History and Scholarship Digital Archives. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Mattei: Chlorofluorocarbon and Its Effects on the Ozone Layer: Is Legisla Chlorofluorocarbon and Its Effects on the Ozone Layer: Is Legislation Sufficient to Protect the Environment? INTRODUCTION "Today's weather will be fair skies, temperature 90 degrees and the ultraviolet light index is high;" the television announcer tells the viewing audience. He continues, "Warning: do not go outdoors without protec- tive clothing and eye protection or risk severe burns and cancer." The place is North Carolina and the time is December, 2005. The ozone layer which once protected us from the sun's harmful ultraviolet light has all but vanished. This is not some scene from a science fiction movie. It can become a realty unless Chlorofluorocarbons are eliminated soon. -

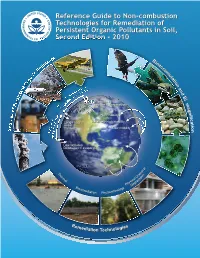

Reference Guide to Non-Combustion Technologies for Remediation of Persistent Organic Pollutants in Soil, Second Edition – 2010

Reference Guide to Non-combustion TechnologiesTechnologies for Remediation of Persistent Organic PollutantsPollutants in Soil, SecondS Edition - 2010 ts B an ii ta oa llu ac ll cc o u P m iic u n lla a t g tii rr o O n O tt g a yc llii n n ll c y attii on n e na orra d tt sso ap a ev ss e d B ii ss nd ee a ss udd nn ii r iitt u tiioo oo r tt siit HighHiHig latitudes e ll a a os m e -- po iidd ep DepositionDDe > evaporation PP e a M dd a ff ff o gg o oo nn t r t ii ss r High mobility oo High mobility ff ii ee pp ss cc cc ee nn aa gg aa rr Relatively high mobility rr Long-range Relatively high mobility n t Long-range n t t t aa uu i r cc i r i oceanic i oceanic o - - o rr o o gg ee transport Low mobility n transport n n n h h S o S o p p L L s s o o m m m m m m m m t t t t t t t t t a a a a a a Low latitudes t t Deposition > evaporation c Deposition > evaporation c ee ff ff ee ”” gg iinn p pp op sh as Grr ll ““G a iic T m h e e h n e C iio rm ll-C tt a a a ll iic ad ys ra h eg P De B iiore ogy med hnoll diiatiion Phytotech RR eemme giieess eddiiaattiioonn TTeecchhnnoolloog Solid Waste EPA 542-R-09-007 and Emergency Response September 2010 (5203P) www.clu-in.org/POPs Reference Guide to Non-combustion Technologies for Remediation of Persistent Organic Pollutants in Soil, Second Edition – 2010 Internet Address (URL) http://www.epa.gov Recycled/Recyclable. -

Reference Guide to Non-Combustion Technologiestechnologies for Remediation of Persistent Organic Pollutantspollutants in Soil, Seconds Edition - 2010

Reference Guide to Non-combustion TechnologiesTechnologies for Remediation of Persistent Organic PollutantsPollutants in Soil, SecondS Edition - 2010 ts B an ii ta oa llu ac ll cc o u P m iic u n lla a t g tii rr o O n O tt g a yc llii n n ll c y attii on n e na orra d tt sso ap a ev ss e d B ii ss nd ee a ss udd nn ii r iitt u tiioo oo r tt siit HighHiHig latitudes e ll a a os m e -- po iidd ep DepositionDDe > evaporation PP e a M dd a ff ff o gg o oo nn t r t ii ss r High mobility oo High mobility ff ii ee pp ss cc cc ee nn aa gg aa rr Relatively high mobility rr Long-range Relatively high mobility n t Long-range n t t t aa uu i r cc i r i oceanic i oceanic o - - o rr o o gg ee transport Low mobility n transport n n n h h S o S o p p L L s s o o m m m m m m m m t t t t t t t t t a a a a a a Low latitudes t t Deposition > evaporation c Deposition > evaporation c ee ff ff ee ”” gg iinn p pp op sh as Grr ll ““G a iic T m h e e h n e C iio rm ll-C tt a a a ll iic ad ys ra h eg P De B iiore ogy med hnoll diiatiion Phytotech RR eemme giieess eddiiaattiioonn TTeecchhnnoolloog Solid Waste EPA 542-R-09-007 and Emergency Response September 2010 (5203P) www.clu-in.org/POPs Reference Guide to Non-combustion Technologies for Remediation of Persistent Organic Pollutants in Soil, Second Edition – 2010 Internet Address (URL) http://www.epa.gov Recycled/Recyclable. -

University of Awaii a Manoa

University of awaii a Manoa Environmental Center Crawford 317. 2550 Campus Road Hono lulu. Hawaii 96822 Telephone (808] 948-7361 Office of the Director RL:0214 HB 117 RELATING TO AEROSOL SPRAYS Statement for House Committee on Water, land Use Development, and Hawaiian Homes Public Hearing 8 March 1977 by Wan-Cheng Chiu, Meteorology Michael J. Chun, Public Health Doak C. Cox~ Environmental Center Peter M. Kroopnick, Oceanography Thomas A. Schroeder, Meteorology Sanford M. Siegel, Botany also A. Daniel Burhans, Environn~ntal Center Gordon, , E. Bigelow, General Science HB 117 would amend Chapter 342 of Hawaii Revised Statutes, relating to environmental qua1itY,to ban the sale of chlorofluorocarbon-based aerosol sprays in Hawaii. This statement on the bill is being submitted for review to the legislative Subcommittee of the Environmental Center of the University of Hawaii, but does not reflect an institutional position of the University. Findings in bill The finding that cert~in chTorofluorocarbon compounds used in aerosol sprays may have significant effect on the ozone layer in the stratosphere is valid, although the complete destruction of the ozone layer that is post~lated in the bill is not a possibility. The findings in the bill as to the malntenance of the ozone layer are valid. The findings that the production of ozone destroying chemicals has been estimated to be increasing at 10 percent per year is valid, although a number " of differing estimates have been made, and most of them overlook the importance of natural production and release of these chemicals. The similar findings as to estimates that have been made as to the health effects of the release of the chlorofluorocarbon compounds is also valid, but subject to the same qualification. -

History of Chlorofluorocarbons

History of Chlorofluorocarbons 1928 : Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) were invented. CFCs were developed as ideal gases used as refrigerants for refrigerators. Because of their special characteristics, inflammability and non-toxicity to human beings, CFCs were massively produced and consumed, particularly in developed countries, after the 1960's. Uses of Chlorofluorocarbons Refrigerants for refrigerators, automobiles and air-conditioners Cleaning agents for semi-conductors and precision parts Foaming agents for insulating materials and packing cushions Propellants for aerosol sprays 1974 : The mechanism of the ozone layer depleted by CFCs was identified. In 1985, the observation of an ozone hole in the Antarctic Pole provided proof that the ozone layer was depleting. 1987 : The Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer was adopted. The Montreal Protocol was adopted as a framework for international cooperation regarding CFC control on the basis of the Vienna Convention for the Protection of the Ozone Layer. Alternatives to CFCs, which do not deplete the ozone layer, were developed. Three CFC alternatives: HFCs, PFCs and SF6, influence global warming. HFCs, PFCs and SF6 are not ozone depleting substances, however, compared to CO2, they have a greater influence on global warming. 1997 : The Kyoto Protocol was adopted. Under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in 1994, the Kyoto Protocol was adopted as a concrete implement to control greenhouse gas emissions. 2005 : The Achievement Plan of the Targets Set -

On Cosmic-Ray-Driven Electron Reaction Mechanism for Ozone Hole and Chlorofluorocarbon Mechanism for Global Climate Change

On Cosmic-Ray-Driven Electron Reaction Mechanism for Ozone Hole and Chlorofluorocarbon Mechanism for Global Climate Change Qing-Bin Lu Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, N2L 3G1, Canada. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Numerous laboratory measurements have provided a sound physical basis for the cosmic-ray driven electron- induced reaction (CRE) mechanism of halogen-containing molecules for the ozone hole. And observed spatial and time correlations between polar ozone loss or stratospheric cooling and cosmic rays have shown strong evidence of the CRE mechanism [Q.-B. Lu, Phys. Rep. 487, 141-167(2010)]. Chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) were also long-known greenhouse gases but were thought to play only a minor role in climate change. However, recent observations have shown evidence of the saturation in greenhouse effect of non-CFC gases. A new evaluation has shown that halocarbons alone (mainly CFCs) could account for the rise of 0.5~0.6 °C in global surface temperature since 1950, leading to the striking conclusion that not CO2 but CFCs were the major culprit for global warming in the late half of the 20th century [Q.-B. Lu, J. Cosmology 8, 1846-1862(2010)]. Surprizingly, a recent paper [J.-W. Grooß and R. Müller, Atmos. Environ. 45, 3508-3514(2011)] has criticized these new findings by presenting “ACE-FTS satellite data”. Here, I show that there exist serious problems with such “ACE-FTS satellite data” because the satellite has essentially not covered the Antarctic vortex in the presented months (especially winter months during which most effective CRE reactions are expected) and that the criticisms do not agree with the scientific facts in the literature.