To What Extent the Program Strengthens the Organic Agricultural Sector?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phytochemical Profiles of Black, Red, Brown, and White Rice from The

Article pubs.acs.org/JAFC Phytochemical Profiles of Black, Red, Brown, and White Rice from the Camargue Region of France Gema Pereira-Caro,† Gerard Cros,‡ Takao Yokota,¶ and Alan Crozier*,† † Joseph Black Building, School of Medicine, College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8QQ, United Kingdom ‡ Laboratoire de Pharmacologie, CNRS UMR 5247 and UniversitéMontpellier 1 and 2, Institut des Biomoleculeś Max Mousseron, Facultéde Pharmacie, 15 avenue Charles Flahault, Montpellier 34093 cedex 05, France ¶ Department of Biosciences, Teikyo University, Utsunomiya 320-8551, Japan ABSTRACT: Secondary metabolites in black, red, brown, and white rice grown in the Camargue region of France were investigated using HPLC-PDA-MS2. The main compounds in black rice were anthocyanins (3.5 mg/g), with cyanidin 3-O- glucoside and peonidin 3-O-glucoside predominating, followed by flavones and flavonols (0.5 mg/g) and flavan-3-ols (0.3 mg/g), which comprised monomeric and oligomeric constituents. Significant quantities of γ-oryzanols, including 24-methylenecy- cloartenol, campesterol, cycloartenol, and β-sitosterol ferulates, were also detected along with lower levels of carotenoids (6.5 μg/ g). Red rice was characterized by a high amount of oligomeric procyanidins (0.2 mg/g), which accounted >60% of secondary metabolite content with carotenoids and γ-oryzanol comprising 26.7%, whereas flavones, flavonols and anthocyanins were <9%. Brown and white rice contained lower quantities of phytochemicals, in the form of flavones/flavonols (21−24 μg/g) and γ- oryzanol (12.3−8.2 μg/g), together with trace levels of the carotenoids lutein and zeaxanthin. Neither anthocyanins nor procyanidins were detected in brown and white rice. -

Research Article Effect of Microwave Cooking on Quality of Riceberry Rice (Oryza Sativa L.)

Hindawi Journal of Food Quality Volume 2020, Article ID 4350274, 9 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/4350274 Research Article Effect of Microwave Cooking on Quality of Riceberry Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Lyda Chin, Nantawan Therdthai , and Wannasawat Ratphitagsanti Department of Product Development, Faculty of Agro-Industry, Kasetsart University, Bangkok 10900, #ailand Correspondence should be addressed to Nantawan erdthai; [email protected] Received 9 October 2019; Revised 8 August 2020; Accepted 13 August 2020; Published 28 August 2020 Academic Editor: Mar´ıa B. Pe´rez-Gago Copyright © 2020 Lyda Chin et al. is is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Microwaves have been applied for cooking, warming, and thawing food for many years. Microwave heating differs from conventional heating and may cause variation in the food quality. is study determined the quality of Riceberry rice (Oryza sativa L.) after microwave cooking using various rice-to-water ratios at three power levels (360, 600, and 900 W). e texture of all microwave-cooked samples was in the range 162.35 ± 5.86 to 180.11 ± 7.17 N and was comparable to the conventionally cooked rice (162.03 N). e total phenolic content (TPC) and the antioxidant activity of the microwave-cooked rice were higher than those of the conventional-cooked rice. Microwave cooking appeared to keep the TPC in the range 241.15–246.89 mg GAE/100 g db and the antioxidant activities based on DPPH and ABTS assays in the ranges 134.24–137.15 and 302.80–311.85 mg·TE/100 g db, respectively. -

Effect of Preparation Method on Chemical Property of Different Thai Rice Variety

Journal of Food and Nutrition Research, 2019, Vol. 7, No. 3, 231-236 Available online at http://pubs.sciepub.com/jfnr/7/3/8 Published by Science and Education Publishing DOI:10.12691/jfnr-7-3-8 Effect of Preparation Method on Chemical Property of Different Thai Rice Variety Cahyuning Isnaini1, Pattavara Pathomrungsiyounggul2, Nattaya Konsue1,* 1Food Science and Technology Program, School of Agro-Industry, Mae Fah Luang University, Muang, Chiang Rai 57100, Thailand 2Faculty of Agro-Industry, Chiang Mai University, Muang, Chiang Mai 50100, Thailand *Corresponding author: [email protected] Received January 15, 2019; Revised February 20, 2019; Accepted March 19, 2019 Abstract Improving benefits and reducing risk of staple food consumption are of interest among researchers nowadays. Rice is the major staple foods consumed in Asia. It has been reported that rice consumption has a positive association with the risk of chronic diseases. The effects of rice variety and preparation process on chemical characteristics of rice were investigated in the current study. Three Thai rice varieties, Khao Dok Mali 105 (KDML 105), Sao Hai (SH) and Riceberry (RB), underwent parboiling or non-parboiling as well as polishing or non- polishing prior to chemical property analysis. It was found that parboiling process possessed greater content of mineral as indicated by ash content as well as fiber and total phenolic content (TPC) and 2,2-diphenyl-1- picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical scavenging activity when compared to non-parboiling treatments, whereas the reduction in amylose and TAC content, GI value and starch digestibility were observed in this sample. On the other hand, polishing process led to reduction in ash, amylose, fiber, TPC and TAC content and DPPH values. -

Degruyter Revac Revac-2021-0137 272..292 ++

Reviews in Analytical Chemistry 2021; 40: 272–292 Review Article Vinita Ramtekey*, Susmita Cherukuri, Kaushalkumar Gunvantray Modha, Ashutosh Kumar*, Udaya Bhaskar Kethineni, Govind Pal, Arvind Nath Singh, and Sanjay Kumar Extraction, characterization, quantification, and application of volatile aromatic compounds from Asian rice cultivars https://doi.org/10.1515/revac-2021-0137 crop and deposits during seed maturation. So far, litera- received December 31, 2020; accepted May 30, 2021 ture has been focused on reporting about aromatic com- Abstract: Rice is the main staple food after wheat for pounds in rice but its extraction, characterization, and fi more than half of the world’s population in Asia. Apart quanti cation using analytical techniques are limited. from carbohydrate source, rice is gaining significant Hence, in the present review, extraction, characterization, - interest in terms of functional foods owing to the presence and application of aromatic compound have been eluci of aromatic compounds that impart health benefits by dated. These VACs can give a new way to food processing fl - lowering glycemic index and rich availability of dietary and beverage industry as bio avor and bioaroma com fibers. The demand for aromatic rice especially basmati pounds that enhance value addition of beverages, food, - rice is expanding in local and global markets as aroma is and fermented products such as gluten free rice breads. considered as the best quality and desirable trait among Furthermore, owing to their nutritional values these VACs fi consumers. There are more than 500 volatile aromatic com- can be used in bioforti cation that ultimately addresses the pounds (VACs) vouched for excellent aroma and flavor in food nutrition security. -

Potential Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Oxidative Properties of Thai Colored-Rice Extracts

POJ 8(1):69-77 (2015) ISSN:1836-3644 Potential anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative properties of Thai colored-rice extracts Thitinan Kitisin1, Nisakorn Saewan2, Natthanej Luplertlop3* 1Department of Anatomy, Faculty of Science, Mahidol University, Ratchathewi, Bangkok, Thailand 2School of Cosmetic Science, Mae Fah Luang University, Muang, Chiang Rai, Thailand 3Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University, Ratchathewi, Bangkok, Thailand *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract In Thailand, there has been growing interest in the use of colored rice extracts as a new source of anti-oxidative and anti- inflammatory effects. This study investigates the effects of different colored rice extracts in terms of their biological content, anti- oxidative activity, and their ability to reduce pro-inflammatory cytokines and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) expression. Various colored rice from different rice cultivating areas in Thailand were used to obtain ethanolic extracts. The biological compounds in colored-rice extracts were determined by Folin-Ciocalteu colorimetric and pH-differential methods. To determine the anti-oxidative properties of colored-rice extract, DPPH radical scavenging, ferrous reducing power, and lipid peroxidation assays were used. The cytotoxicity of colored rice extracts was determined by MTT assay on a human promyelocytic leukemia (HL-60) cell line in vitro. The inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, NF-κB) and MMP expression in LPS-induced HL-60 cells was determined by ELISA assay. Moreover, MMP activity was determined by gelatinolytic zymography. The results found that red (Mun Poo, MP) rice exhibited high anti-oxidative activity and reduced pro-inflammatory cytokines and MMP-2 expression in LPS-induced HL-60 cells. -

J I T M M 2 0

JOINT INTERNATIONAL TROPICAL MEDICINE MEETING 2018 “INNOVATION, TRANSLATION, AND IMPACT IN TROPICAL MEDICINE” 12 – 14 DECEMBER 2018 AMARI WATERGATE HOTEL, BANGKOK, THAILAND ABSTRACTS Oral Presentations J I T M M 2 0 1 8 Organizers 4 Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University 4 SEAMEO TROPMED Network 4 TROPMED Alumni Association 4 The Parasitology and Tropical Medicine Association of Thailand Co-organizers 9 Department of Disease Control Ministry of Public Health (MOPH) 9 Mahidol - Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit (MORU) 2 Wednesday 12 December 2018 Opening Session 09.00-09.45 Watergate Ballroom OPENING CEREMONY BY ORGANIZERS AND CO-ORGANIZERS Report by: Prof. Srivicha Krudsood Chair, JITMM2018 Scientific Committee WELCOME ADDRESS Dr. Sombat Thanphasertsuk Senior Expert in Prevention Medicine, Department of Disease Control, Thailand Ministry of Public Health WELCOME ADDRESS Mr. David Burton Chief Operating Officer, Mahidol-Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit (MORU) OPENING REMARKS Assoc. Prof. Pratap Singhasivanon Chairman, JITMM2018 Organizing Committee TROPMED Alumni Award Presentation Presented by: Assoc. Prof. Supranee Changbumrung Joint International Tropical Medicine Meeting (JITMM) 2018 “INNOVATION, TRANSLATION, AND IMPACT IN TROPICAL MEDICINE” 3 AWARD RECIPIENTS: Prof. Akira Kaneko Professor of Global Health, Department of Microbiology, Tumor and Cell biology, Karolinska Institutet, Sweden Prof. Dr. Tawadchai Suppadit Vice President, Planning and Development Strategies, Walailak University, Thailand Dr. Twatchai Srestasupana Director, Maesot General Hospital, Mae Sot, Tak, Thailand Joint International Tropical Medicine Meeting (JITMM) 2018 “INNOVATION, TRANSLATION, AND IMPACT IN TROPICAL MEDICINE” 4 Wednesday 12 December 2018 09.45-10.30 Watergate Ballroom S1: The 24th Chamlong-Tranakchit Lecture Chairperson: Pratap Singhasivanon Keynote Speaker: The safe and effective radical cure of malaria Prof. -

Private Chef's Table 2019 Immerse Yourself in a Private Dining

Private Chef’s Table 2019 Immerse yourself in a private dining experience and taste the secrets of Singapore’s best home chefs Heritage Food Chef Eric Teo, 56 Celebrity Chef Eric Teo brings more than 30 years of culinary experience to the F&B industry in Singapore. The culinary line-up for Private Chef’s Table is specially curated by Celebrity Chef Eric Teo. In this event, Chef Eric Teo acts as a mentor to the home chefs, curating the menu and culinary themes: Heritage Food and Modern Takes, thus presenting dishes that stay true to their traditional roots and also dishes with modern interpretations. Date: 5 Jul 2019 | Time: 7-10pm Starter Cantonese Lobster & Avocado Soup Paired with Perrier-Jouët Grand Brut Teochew Heavenly King Braised Crab Meat Soup Paired with Perrier-Jouët Grand Brut Main Hokkien Kobe Beef, Bell Peppers Paired with Martell Cordon Bleu Golden Chef Abalone, King Oyster Mushroom & Asparagus Paired with Martell XO Hakka Grandma Fish Noodles Paired with Martell XO Dessert Hainan Slow Cooked Bird Nest Paired with Martell XO 1 Eat Moreish (Yun Hui, 33) As someone who lives for food experiences, Yun Hui enjoys sharing good food, fine-tuned with his own twists and style. You will find classic dishes, inspired by the cooking matriarch of the household - his grandmother. “Eat Moreish” features nosh that are zhng-ed up with a personal touch, fine-tuned with many trials and errors. The item on the menu Yun Hui is most proud of would be the Lor Bak Rice, with pork belly teased on low heat for maximum flavour. -

HCS Website List As of 30 June 2021 Working File.Xlsx

HCS Product List - By Brand Name (July 2021) Brand Name & Product Name Package Size (Lim Traders) Chicken Breaded Patties 1.8 kg 100PLUS ACTIVE Non-Carbonated Drink 1.5 L 100PLUS ACTIVE Non-Carbonated Drink 12 X 300 ml 100PLUS ACTIVE Non-Carbonated Drink 300 ml 100PLUS ACTIVE Non-Carbonated Drink 500 ml 100PLUS ACTIVE Non-Carbonated Drink 6 X 300 ml 100PLUS Hydration Bar 4 X 75 ml 100PLUS Hydration Bar 75 ml 100PLUS Lemon Lime 1.5 L 100PLUS Lemon Lime 325 ml 100PLUS Lemon Lime 500 ml 100PLUS Orange 1.5 L 100PLUS Orange 500 ml 100PLUS Original 1.5 L 100PLUS Original 12 X 325 ml 100PLUS Original 325 ml 100PLUS Original 500 ml 100PLUS Original 6 X 325 ml 100PLUS Zero Sugar 1.5 L 100PLUS Zero Sugar 12 X 1.5 L 100PLUS Zero Sugar 24 X 325 ml 100PLUS Zero Sugar 24 X 500 ml 100PLUS Zero Sugar 325 ml 100PLUS Zero Sugar 500 ml 100PLUS Zero Sugar 6 X 325 ml 333 Super Refined Blended Vegetable Oil 1 X 17 kg 3A 100% Pure Black Sesame Oil 320 ml 3A 100% Pure Black Sesame Oil 750 ml 3A 100% Pure White Sesame Oil 320 ml 3A 100% Pure White Sesame Oil 750 ml 3A Black Pepper Sauce 250 ml 3A Brown Rice Vermicelli 500 g 3A Crispy Prawn Chilli 180 g 3A Crispy Prawn Chilli 320 g 3A Ginseng Herbal Soup Mix 40 g 3A Instant Tom Yum Paste 227 g 3A Klang Bakuteh Herbs & Spices Mix 35 g 3A Premium Sugar Free Black Soybean Soy Sauce 400 ml 3-Elephants Thai Organic Hom Mali Brown Rice 1 kg 3-Elephants Thai Organic Hom Mali Brown Rice 2 kg 3-Elephants Thai Organic Mixed Brown Rice 1 kg 3-Elephants Thai Organic Mixed Brown Rice 2 kg 3-Elephants Thai Organic Red Brown -

2021) Journal Homepage

International Food Research Journal 28(2): 386 - 392 (April 2021) Journal homepage: http://www.ifrj.upm.edu.my Optimisation of the dielectric barrier discharge to produce Riceberry rice flour retained with high activities of bioactive compounds using plasma technology 1Settapramote, N., 2,5Laokuldilok, T., 3Boonyawan, D. and 4,5*Utama-ang, N. 1Division of Product Development Technology, Faculty of Agro-Industry, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50100, Thailand 2Division of Marine Product Technology, Faculty of Agro-Industry, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50100, Thailand 3Plasma and Beam Physics Research Facility, Department of Physics and Materials Science, Faculty of Science, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand 4Division of Product Development Technology, Faculty of Agro-Industry, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50100, Thailand 5Cluster of High Value Product from Thai Rice for Health, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50100, Thailand Article history Abstract Received: 3 December 2019 Riceberry rice is a hybrid rice that contains polyphenol compounds, anthocyanin, and high Received in revised form: antioxidants. Plasma technology has been used to improve the quality of rice and rice flour. 2 April 2020 Some conditions of the plasma process can be altered to get the combination that can achieve Accepted: 7 May 2020 maximum result. The present work aimed to identify the optimal combination of a plasma treatment condition by varying three variables: time (3 - 10 min), power (140 - 180 W), and oxygen flow rate (0.0 - 0.8 L/min) in improving the nutrient and antioxidant agent of Keywords Riceberry rice flour. The increase in time and power significantly increased the percenatge of dielectric barrier the scavenging ability of the free radical 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), peonidin discharge (DBD), 3-glucoside, cyanidin 3-glucoside, and total anthocyanin; while the decrease in oxygen plasma technology, significantly decreased all the parameters analysed. -

(Oryza Sativa) Rice Flour As Gluten Free Ingredient in Bread

foods Article Physicochemical Properties of Hom Nil (Oryza sativa) Rice Flour as Gluten Free Ingredient in Bread Lalana Thiranusornkij 1,2, Parichart Thamnarathip 2, Achara Chandrachai 1, Daris Kuakpetoon 3 and Sirichai Adisakwattana 4,* 1 Technopreneurship and Innovation Management Program, Graduate School, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok 10330, Thailand; [email protected] (L.T.); [email protected] (A.C.) 2 KCG Excellence Center, KCG Corporation Co., Ltd., Thepharak Rd., Bangpleeyai, Bangplee, Samutprakarn 10540, Thailand; [email protected] 3 Department of Food Technology, Faculty of Science, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok 10330, Thailand; [email protected] 4 Department of Nutrition and Dietetics, Faculty of Allied Health Sciences, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok 10330, Thailand * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +66-2-218-1099 (ext. 111) Received: 10 July 2018; Accepted: 25 September 2018; Published: 27 September 2018 Abstract: Hom Nil (Oryza sativa), a Thai black rice, contains polyphenolic compounds which have antioxidant properties. The objective of this study was to investigate physicochemical properties of Hom Nil rice flour (HN) and its application in gluten free bread by using Hom Mali 105 rice flour (HM) as the reference. The results demonstrated that HN flour had significantly higher average particle sizes (150 ± 0.58 µm), whereas the content of amylose (17.6 ± 0.2%) was lower than HM flour (particle sizes = 140 ± 0.58 µm; amylose content = 21.3 ± 0.6%). Furthermore, HN contained higher total phenolic compounds (TPC) (2.68 ± 0.2 mg GAE/g flour), total anthocyanins (293 ± 30 mg cyanidin-3-glucoside/g flour), and the ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) (73.5 ± 1.5 mM FeSO4/g) than HM flour (TPC = 0.15 mg GAE/g flour and FRAP = 2.24 mM FeSO4/g flour). -

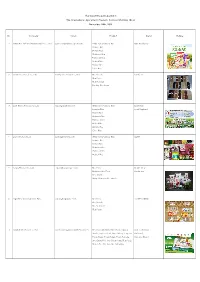

Rice) November 20Th, 2019 by Category

Thai Exporters participating in The International Agricultural Products Business Matching (Rice) November 20th, 2019 by Category No. Company E-mail Product Brand Picture 1 Patum Rice Mill and Granary Public Co., Ltd. [email protected] White non-glutinous Rice Mah Boonkrong Jasmine Rice Broken Rice Glutinous Rice Parboiled Rice Husked Rice Organic Rice Color Rice 2 Family Tree Foods Co., Ltd. Family Tree Foods Co., Ltd. Rice Noodle Family Tree Rice Pasta Rice Porridge Drinking Rice Straw 3 Excel Rice & Products Co.,Ltd. [email protected] White non-glutinous Rice Excel Rice Jasmine Rice Excel Elephant Broken Rice Glutinous Rice Parboiled Rice Husked Rice Organic Rice Color Rice 4 Olam (Thailand) Ltd. [email protected] White non-glutinous Rice OLAM Jasmine Rice Broken Rice Glutinous Rice Parboiled Rice Husked Rice 5 Burapa Prosper Co., Ltd. [email protected] Rice Flour Double Bear Glutinous Rice Flour Panda Star Rice Starch Waxy Glutinous Rice Starch 6 Bright Time Intertrade Ltd., Part. [email protected] Rice Flour 3 CHEF'S BRAND Rice Noodle Rice Vermicelli Rice Paper 7 Bangkok Inter Food Co., Ltd. [email protected] Rice Flour, Glutinous Rice Flour, Tapioca Jade Leaf Brand, Starch, Tapioca Pearl, Mixed Flour, Tempura BIF Brand, Flour, Crispy Flour, Bakery Flour, Pancake Kangaroo Brand and Crepe Mix Flour Gluten Free, Rice Pasta, Gluten Free Product, Mochi Daifuku by Category No. Company E-mail Product Brand Picture 8 K.P. Green Co., Ltd. [email protected] White non-glutinous Rice Diamond Rooster Jasmine Rice Glutinous Rice Organic Rice Color Rice 9 Siam Diamond Exportrice Co., Ltd. -

Some Strategies for Utilization of Rice Bran Functional Lipids And

Journal of Oleo Science Copyright ©2018 by Japan Oil Chemists’ Society doi : 10.5650/jos.ess17257 J. Oleo Sci. 67, (6) 669-678 (2018) REVIEW Some Strategies for Utilization of Rice Bran Functional Lipids and Phytochemicals Phumon Sookwong1* and Sugunya Mahatheeranont1, 2 1 Rice and Cereal Chemistry Research Laboratory, Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, THAILAND 2 Center of Excellence for Innovation in Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, THAILAND Abstract: Rice bran contains a great amount of functional lipids and phytochemicals including γ-oryzanols, tocotrienols, and tocopherols. However, utilization of those compounds is limited and needs some proven guidelines for better implementation. We introduce some effective strategies for the utilization of rice functional lipids, including an introduction of pigmented rice varieties for better bioactive compounds, bio- fortification of rice tocotrienols, plasma technology for improving rice phytochemicals, supercritical CO2 extraction of high quality rice bran oil, and an example on the development of tocotrienol-fortified foods. Key words: rice, pigmented rice, phytochemicals, functional lipids, antioxidants 1 Introduction tant role in reducing plasma lipid and lipoprotein Rice(Oryza sativa)is one of the most important crops cholesterol concentrations7). T3s fight cancer cells by tar- in the world with more than half of its population consum- geting multiple cell signaling pathways8). Polyphenols, ing rice as their main energy source. More than 700 million vitamin E and carotenoids help prevent oxidative damage metric tons of rice is being produced annually worldwide1). to DNA and other tissues9). The standard of rice production in regards to quality im- Despite their health advantages, rice bran functional provement of product in order to promote health and lipids are hardly consumed on a daily basis because rice welfare has therefore been encouraged profoundly.