Capricious Concrete: on Plasticity in Material and Method

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Simulating Self Supporting Structures

Simulating Self Supporting Structures A Comparison study of Interlocking Wave Jointed Geometry using Finite Element and Physical Modelling Methods Shayani Fernando1, Dagmar Reinhardt2, Simon Weir3 1,2,3University of Sydney, Australia 1,2,3{shayani.fernando|dagmar.reinhardt|simon.weir}@sydney.edu.au Self-supporting modular block systems of stone or masonry architecture are amongst ancient building techniques that survived unchanged for centuries. The control over geometry and structural performance of arches, domes and vaults continues to be exemplary and structural integrity is analysed through analogue and virtual simulation methods. With the advancement of computational tools and software development, finite and discrete element modeling have become efficient practices for analysing aspects for economy, tolerances and safety of stone masonry structures. This paper compares methods of structural simulation and analysis of an arch based on an interlocking wave joint assembly. As an extension of standard planar brick or stone modules, two specific geometry variations of catenary and sinusoidal curvature are investigated and simulated in a comparison of physical compression tests and finite element analysis methods. This is in order to test the stress performance and resilience provided by three-dimensional joints respectively through their capacity to resist vertical compression, as well as torsion and shear forces. The research reports on the threshold for maximum sinusoidal curvature evidenced by structural failure in physical modelling methods and finite element analysis. Keywords: Mortar-less, Interlocking, Structures, Finite Element Modelling, Models INTRODUCTION / CONTEXT OF RESEARCH used, consideration of relative position of each block Self-supporting stone or masonry architecture is the within the overall geometry, and joints of a block as- arrangement of modular elements that are struc- sembly become the driving factor that determine the turally performative and hold together through ver- architecture. -

2020.06.04 Lecture Notes 10Am Lecture 3 – Estereostàtic (Stereostatic: Solid + Force of Weight Without Motion)

2020.06.04 Lecture Notes 10am Lecture 3 – Estereostàtic (stereostatic: solid + force of weight without motion) Welcome back to Antoni Gaudí’s Influence on the Contemporary Architecture of Barcelona and Bilbao. Housekeeping Items for New Students: Muting everyone (background noise) Questions > Raise Hand & Chat questions to Erin (co-host). 5 to 10 minute break & 10 to 15 minutes at end for Q&A 2x (Calvet chair) Last week, 1898 same time Gaudí’s finishing cast figures of the Nativity Façade. Started construction on Casa Calvet (1898-1900) influence of skeletons on chair, bones as props/levers for body movement, develops natural compound curved form. Gaudí was turning toward nature for inspiration on structure and design. He studied the growth and patterns of flowers, seeds, grass reeds, but most of all the human skeleton, their form both functional and aesthetic. He said, these natural forms made up of “paraboloids, hyperboloids and helicoids, constantly varying the incidence of the light, are rich in matrices themselves, which make ornamentation and even modeling unnecessary.” 1x (Calvet stair) Traditional Catalan method of brickwork vaulting (Bóvedas Tabicadas), artform in stairways, often supported by only one wall, the other side open to the center. Complexity of such stairs required specialist stairway builders (escaleristas), who obtained the curve for the staircase vaults by hanging a chain from two ends and then inverting this form as a guide for laying the bricks to the arch profile. 1x (Vizcaya bridge) 10:15 Of these ruled geometries, one that he had studied in architectural school, was the catenary curve: profile resulting from a cable hanging under its own weight (uniformly applied load)., which five years earlier used for the Vizcaya Bridge, west of Bilbao (1893), suspension steel truss. -

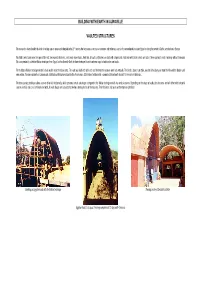

Building with Earth in Auroville Vaulted Structures

BUILDING WITH EARTH IN AUROVILLE VAULTED STRUCTURES The research in Auroville with this kind of roofing aims to revive and integrate in the 21st century the techniques used in past centuries and millennia, such as those developed in ancient Egypt or during the period of Gothic architecture in Europe. This R&D seeks to increase the span of the roof, decrease its thickness, and create new shapes. Note that all vaults and domes are built with compressed stabilised earth blocks which are laid in “Free spanning” mode, meaning without formwork. This was previously called the Nubian technique, from Egypt, but the Auroville Earth Institute developed it and found new ways to build arches and vaults. The traditional Nubian technique needed a back wall to stick the blocks onto. The vault was built arch after arch and therefore the courses were laid vertically. The binder, about 1 cm thick, was the silty-clayey soil from the Nile and the blocks used were adobe. The even regularity of compressed stabilised earth block produced by the Auram press 3000 allows building with a cement-stabilised earth glue of 1-2 mm only in thickness. The free spanning technique allows courses to be laid horizontally, which presents certain advantages compared to the Nubian technique which has vertical courses. Depending on the shape of vaults, the structures are built either with horizontal courses, vertical ones or a combination of both. All vault shapes are calculated to develop catenary forces in the masonry. Their thickness and span can therefore be optimised. Building -

Either in Depth Or on a Hillside

TRAINING COURSES TRAINING OUTCOME WITH PHOTOS Trainees are coming from all over the world for getting theoretical and practical knowledge on earth architecture and other appropriate building technologies. They enjoy working with their hands for building various things. Please note that when the information below does mention the location of the training course, it means that the training course was in Auroville. ****************************************************************************************************** 2010 SEPTEMBER 13th to 25th – TWO WEEK COURSE ON ARCHES, VAULTS AND DOMES 29 trainees from 4 countries (23 Indians, 4 French, 1 Saudi Arabian, 1 American) First week: studying the stability of arches and vaults Teaching how to build an arch Group photo of AVD September 2010 batch ****************************************************************************************************** 2010 AUGUST 30th to SEPTEMBER 4th – TWO WEEK COURSE ON PRODUCTION AND USE OF CSEB 37 trainees from 6 countries (28 Indians, 1 British, 4 French, 2 Germans, 1 Italian, 1 Ugandan) Production of CSEB with the Auram Press 3000 Steel mat preparation for composite column Group photo of CSEB September 2010 batch ****************************************************************************************************** 2010 JUNE 28th to JULY 3rd – ONE WEEK COURSE ON PRODUCTION AND USE OF CSEB 21 trainees from 3 countries (17 Indians, 1 French, 1 Spanish, 2 Egyptians) Preparation for plinth beam Casting of plinth beam Identification of soils ****************************************************************************************************** -

Optimal Forms of Two-Pin Arches

7th International Conference on Modern Research in Civil Engineering, Architectural & Urban Development October 19-21, 2018 Munich - Germany Optimal forms of two-pin arches Asal Pournaghshband PhD graduate Warwick University [email protected] Abstract A comprehensive review of the response of two-pin arches including catenary, parabolic and circular form to loading is presented. The effects of form on the arch structural response for static loading and span-to- height ratios (L:h) ranging from 2 to 8 are presented using finite element solution provided by the GSA software. Results have shown that circular arches represent least optimal shape, exhibiting high combined stresses and bending moments, particularly for the L:h ratio of 2 (semi-circular arch). The optimum L:h ratio for a circular rib arch is between 4 and 6, but the stresses that develop in it are still higher than in parabolic or catenary arches. This is with regard to the pure arch behavior for L:h≤5. The minimum of the combined compressive stresses in parabolic and catenary arches are observed at L:h ratio between 2 and 4. The parabolic arch demonstrated lower structural action effects when the uniformly distributed load (UDL) is greater than the self-weight (SW). Overall, the findings demonstrate that the response of 2-pin arch forms to applied loading is critically dependent on the arch form and its shape governed by the L:h ratio. Keywords: form; span-to-height; combined stress; bending moment; optimal 100 7th International Conference on Modern Research in Civil Engineering, Architectural & Urban Development October 19-21, 2018 Munich - Germany 1. -

Structural Design in the Work of Gaudi

G 2006 University of Sydney All rights reserved. Architectural Science Review www.arch.usyd.edu.au/asr Volume 49.4, pp 324-339 Invited Paper Structural Design in the Work of Gaudi Santiago Huerta Department of Structural Design, Escuela Ticnica Superior de Arquitecrura, Universidad Politecnica de Madrid, Avida Juan de Herrera 4, 28040 Madrid, Spain Email: [email protected] Invited Paper: Received 3 April 2006; accepted 20 May 2006 Abstract: The work of Gaudi embraces all the facets of architectural design. The present paper studies the analysis and design of masonry arches, vaults and buildings. It is well known that Gaudi used hanging models and graphical methods as design tools. These methods can be traced back to the end of the 17th Century. In addition, it was not original the use of equilibrated, catenarian forms. What was completely original was the idea of basing all the structural design in considerations of equilibrium. Gaudi also employed unusual geometrical forms for some of his vaults and ruled surfaces, showing a deep structural insight. Finally, he designed tree-forms of equilibrium for the supports of the vaults in the Sagrada Familia. In the present paper Gaudi's equilibrium methods are studied with some detail, stressing their validity within the frame of Limit Analysis. Keywords: Structural design; Gaudi; Masonry arches; Vaults; Catenarian forms; Equilibrium methods; Limit analysis Introduction Antoni ~audi(1852-1 926) was aMaster Builder. His work cov- the circle (roman, pointed, basket-handle, etc.), he used arches with ers all aspects of architecture: layout, ornamentation and stability. non-circular shapes: parabolic or These arches are already He also incorporates other arts: sculpture (particularly), painting, in ~~~df~first buildings, seen in Figures 1 and 2. -

Masonry Structures Modelled As Assemblies of Rigid Blocks

UNIVERSITY OF NAPLES FEDERICO II School of Polytechnic and Basic Sciences Department of Structures for Engineering and Architecture PH.D. PROGRAMME IN STRUCTURAL, GEOTECHNICAL AND SEISMIC ENGINEERING - XXIX CYCLE COORDINATOR: PROF. LUCIANO ROSATI FABIANA DE SERIO Ph.D. Thesis MASONRY STRUCTURES MODELLED AS ASSEMBLIES OF RIGID BLOCKS TUTORS: PROF. ING. MARIO PASQUINO PROF. ARCH. MAURIZIO ANGELILLO 2017 Acknowledgements During the course of my studies, I have had the privilege of knowing an exceptional life mentor: I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Professor Mario Pasquino, who guided me since my bachelor’s degree, and then gave me the opportunity to make this PhD experience possible, assisting me professionally and, especially, humanly. My biggest gratitude goes to an extraordinary Professor, Maurizio Angelillo, who believed in me and motivated my interest in the matter, with his invaluable advice, knowledges and unwavering guidance. It was because of his intuitions and persistent help that the development of this dissertation has been possible. A special ‘thank you’ goes to Professor Antonio Gesualdo and my colleague Antonino Iannuzzo, our cooperation and friendship was particularly inspiring and cheering during these years. I am profoundly grateful to the Coordinator of this PhD course, Professor Luciano Rosati, for his support during these three years and for the interest showed in my research. In addition, I would also like to sincerely thank the reviewers of my PhD thesis, Professor Santiago Huerta and Professor Elio Sacco, their opinion and compliments have been very important to me, representing a big encouragement to continue in the field of scientific research. I am extremely grateful for the loving care of my adorable husband Alessandro, for following me closely during this work experience, for his invaluable presence and constant encouragement and help, even when being far away. -

Creative Interface for Constructing Earthbag Resource Objects

Creative Interface for Constructing Earthbag Resource Objects Doutoramento em Arquitetura Especialidade em desenho e computação DEBORAH MACÊDO DOS SANTOS Orientador: Professor Doutor José Nuno Beirão Tese especialmente elaborada para a obtenção do grau de doutor Documento definitivo Julho, 2020 Creative Interface for Constructing Earthbag Resource Objects Doutoramento em Arquitetura Especialidade em desenho e computação DEBORAH MACÊDO DOS SANTOS Orientador: Professor Doutor José Nuno Beirão Juri: Presidente: Doctor of Philosophy Luís António dos Santos Romão, Professor Associado da Faculdade de Arquitetura da Universidade de Lisboa. Vogais: - Doutor Carlos Nuno Lacerda Lopes, Professor Associado da Faculdade de Arquitectura da Universidade do Porto; - Doutora Alexandra Cláudia Rebelo Paio, Professora Auxiliar do ISCTE-IUL; - Doutor Luís Miguel Cotrim Mateus, Professor Auxiliar da Faculdade de Arquitetura da Universidade de Lisboa; - Doutor Filipe Alexandre Duarte González Migães de Campos, Professor Auxiliar da Faculdade de Arquitetura da Universidade de Lisboa; - Doutor José Nuno Dinis Cabral Beirão, Professor Auxiliar da Faculdade de Arquitetura da Universidade de Lisboa. Tese especialmente elaborada para a obtenção do grau de doutor Documento definitivo Julho, 2020 v Dedicatória Aos que acreditam. vi vii Epigraph “In the beginning, God created heaven and earth.” Genesis 1, 1 viii ix Acknowledgements Agradeço ao Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), pela manutenção da bolsa de estudos (201904/2015-2). Agradeço a Universidade Federal do Cariri, pela manutenção do afastamento remunerado, para missão no exterior de capacitação profissional. Agradeço ao Centro de Investigação em Arquitetura, Urbanismo e Design (CIAUD) pelo apoio em congressos e publicações. Agradeço do grupo de estudos em desenho e computação (DCG), que foi onde estive durante toda escrita desta tese. -

Flying Buttress and Pointed Arch in Byzantine Cyprus

Flying Buttress and Pointed Arch in Byzantine Cyprus Charles Anthony Stewart Though the Byzantine Empire dissolved over five hundred years ago, its monuments still stand as a testimony to architectural ingenuity. Because of alteration through the centuries, historians have the task of disentangling their complex building phases. Chronological understanding is vital in order to assess technological “firsts” and subsequent developments. As described by Edson Armi: Creative ‘firsts’ often are used to explain important steps in the history of art. In the history of medieval architecture, the pointed arch along with the…flying buttress have receive[d] this kind of landmark status.1 Since the 19th century, scholars have documented both flying buttresses and pointed arches on Byzantine monuments. Such features were difficult to date without textual evidence. And so these features were assumed to have Gothic influence, and therefore, were considered derivative rather than innovative.2 Archaeological research in Cyprus beginning in 1950 had the potential to overturn this assumption. Flying buttresses and pointed arches were discovered at Constantia, the capital of Byzantine Cyprus. Epigraphical evidence clearly dated these to the 7th century. It was remarkable that both innovations appeared together as part of the reconstruction of the city’s waterworks. In this case, renovation was the mother of innovation. Unfortunately, the Cypriot civil war of 1974 ended these research projects. Constantia became inaccessible to the scholarly community for 30 years. As a result, the memory of these discoveries faded as the original researchers moved on to other projects, retired, or passed away. In 2003 the border policies were modified, so that architectural historians could visit the ruins of Constantia once again.3 Flying Buttresses in Byzantine Constantia Situated at the intersection of three continents, Cyprus has representative monuments of just about every civilization stretching three millennia. -

Low-Cost Housing Using Sustainable Materials and Catenary Shapes

Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Civil, Structural and Transportation Engineering (ICCSTE'19) Ottawa, Canada – June, 2019 Paper No. ICCSTE 170 DOI: 10.11159/iccste19.170 Low-cost Housing Using Sustainable Materials and Catenary Shapes Mitchell Gohnert University of the Witwatersrand 1 Jan Smuts Ave, Johannesburg, South Africa [email protected] Abstract - The United Nations estimates that approximately 12% of the world’s population live in slums, which is about 860 million people. The use of the word “slums” infers that its occupants live in informal housing, or housing that does not comply with building codes and regulations, are inferior in construction and often present health hazards. Although every nation is inherently responsible to ensure that this basic need is met, usually finances and social prioritization are the inhibiting factors. In fact, the rate of increase in slums is exceeding population growth. The world is digressing. This paper is therefore an attempt to provide an alternative solution to the housing problem. A housing solution should be affordable, include sustainable building materials and optimize the structural shape. A prototype house is presented, which incorporates cement-stabilized earth blocks (CSEB) and blocks made from recycled building material. A typical pitched roof is also replaced with a catenary brick vault. Keywords: Cement stabilized earth blocks, Sustainable building materials, Dry-stack construction, Low-cost housing, Catenary vaults, Shell structures. 1. Introduction UN Habitat estimates that nearly one billion people will live in slums in the next 20 years. South Africa is a developing country, and is faced with housing shortages that appear to be insurmountable. -

Geology of the Archeological Hills and Monuments, Examples from Iraq

Journal of Earth Sciences and Geotechnical Engineering, vol. 6, no.2, 2016, 1-28 ISSN: 1792-9040 (print), 1792-9660 (online) Scienpress Ltd, 2016 Geology of the Archeological Hills and Monuments, Examples from Iraq Varoujan K. Sissakian1, Ayda D. Abdul Ahad2, Nadhir Al-Ansari3 and Sven Knutsson3 Abstract Iraq is the cradle of many civilizations; therefore, it is very rich in archeological sites, which are represented in different forms; among them are the archeological hills and monuments. Hundreds of archeological hills and monuments are located in different parts of Iraq, but the majority of the hills are located in the Mesopotamia and Low Mountainous Province; with less abundant in the Jazira Province. The isolated archeological hills are of two different forms: Either are in form of dumping soil to a certain height to build the hill, or has gained their heights due to the presence of multi stories of civilizations. In both cases, the geological setting has played a big role in the formation of the isolated archeological hills. The archeological isolated hills, which are built by soil dumping are usually of conical shape; flat topped and limited sizes; with heights not more than 10 m and base diameter of (20 – 100) m. They can be seen from far distances that attain to few kilometers. Since they are usually built in flat areas and are believed to be used as watching towers. However, those which are present in the Mesopotamia Province are smaller in size; not more than (3 – 5) m in height and about 10 m in base diameter; also with conical shape, they are called as "Ishan". -

A Ctesiphon Arch V.I.P. Latrine

A SANITATION: GLOVER and BRESLIN 25th WEDC Conference Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 1999 INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT FOR WATER SUPPLY AND SANITATION A ctesiphon arch V.I.P. latrine Dr Peter Glover and Ned Breslin, South Africa THIS PAPER DESCRIBES and illustrates the Arch VIP purely as an insitue formwork. Wall thicknesses can be as toilet structures that are currently being developed in rural low as 25mm. Hessian and mortar also provide a low cost Zululand (Nongoma KwaZulu). The structures, in the (and highly effective) ventpipe and pit cover. form of a catenary, are produced entirely of unreinforced The Archloo superstructure is produced by draping mortar plastered hessian which is formed by temporary (stapling) course hessian between two catenary forms. This wooden supports. The overall cost of the structures is hessian is then painted with a thin slurry, and then a thin remarkably low, and their strength and durability out- layer of plaster is added. Up to 3 layers of plaster are added, standing. allowing drying time (4-7hrs) between layers. Once the outside layer has gone off, the structure is The catenary arch already self supporting, and the wooden forms can be A catenary is the shape that is made when a chain hangs removed. between two supports. The chain links are not rigid, so therefore cannot transfer a bending moment. The shape the Pit lining chain makes is therefore such that the chain is under pure The hessian plaster system can also be adopted for the rest tension. If gravity is reversed, or the shape inverted, it of the structure. 3-4 pockets of cement will entirely line a represents a shape that under equal load distribution will be 1.5x3m deep pit using hessian as a base for the plaster.