Talk Radio/Shock Radio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sirius Satellite Radio Inc

SIRIUS SATELLITE RADIO INC FORM 10-K (Annual Report) Filed 02/29/08 for the Period Ending 12/31/07 Address 1221 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 36TH FLOOR NEW YORK, NY 10020 Telephone 2128995000 CIK 0000908937 Symbol SIRI SIC Code 4832 - Radio Broadcasting Stations Industry Broadcasting & Cable TV Sector Technology Fiscal Year 12/31 http://www.edgar-online.com © Copyright 2008, EDGAR Online, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Distribution and use of this document restricted under EDGAR Online, Inc. Terms of Use. Table of Contents Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 F ORM 10-K ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR FISCAL YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2007 OR TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 FOR THE TRANSITION PERIOD FROM TO COMMISSION FILE NUMBER 0-24710 SIRIUS SATELLITE RADIO INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 52 -1700207 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer Identification Number) incorporation of organization) 1221 Avenue of the Americas, 36th Floor New York, New York 10020 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (212) 584-5100 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Name of each exchange Title of each class: on which registered: Common Stock, par value $0.001 per share Nasdaq Global Select Market Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None (Title of class) Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. -

Ike's Stand on Berlin

Mois Tim rry The Kmanuel'’%9nirchnven of the Kmahuel Lutheran Church will Great Chiefs Visit District Leaders A b o u t T o w n meet tomorrow night at 7:30 at the church. A film, "Tour Lhtheran Red Men' Monday Named-for Drive parkhi^'Chirge Th« ZJpeer Qub will hold tU World Federation," depicting the WMkly Mtbaek party in th« club* meeting of Lutherans' from many M lantonomoh Tribe 'N o. 58, York Btrangfeld, dl^lrman of The Riv. .Charles ReynoliH. as-; rooms Saturday night starting at nations In Minneapolis. Minn,, In the Residential Divieion OTAhe Red, . Follows Aeeident sociate minister of South Aletho- ; IpRM, will hold ita regular meet dist Church, will talk and show 8:80 o’clock. 1057, will be shown. Cross Fund'Drive, has annolmced ing'in Tinker hall Monday night Harold V. Andrews, 48, of East slides of India at the meeting ot Ramrrationa are now being ac^ Scandls Lodge. Order of Vsaa. at .8 o'clock. Past sachems' night the following district majors: Walpole, Mass., wgsiarrested and the Young Adults of the Emanuel; \captad at the British .American will hold its monthly meeting to will be observed, the chairs to be Mrs. Edwfird Catrigan, Mra. Ar arged, with Improper parking Lutheran Church tomorrow night Suburbia TodaV Cnub for the annual St, Patrick’.^ night St 8 o'clock in Grange Hall. occupW by past sachems, f | thur StMle, Mrs. Jerome Walsh, yesleyday morning after a oar hit at 7:30 in the chapel. Sbme*€k)t 51c an Hour Dtbtca Saturday, March. H- Art Card playing will be the program Members aie requested to make : Mrs. -

THE BEST :BROADCAST BRIEFING in CANADA Thursday, July 6, 2006 Volume 14, Number 7 Page One of Three

THE BEST :BROADCAST BRIEFING IN CANADA Thursday, July 6, 2006 Volume 14, Number 7 Page One of Three DO NOT RETRANSMIT THIS ENERAL: The CRTC’s annual broadcast monitoring report shows PUBLICATION BEYOND YOUR Canadians are watching a bit more TV, listening to a bit less radio RECEPTION POINT Gand accessing the Internet in record numbers. The Commission also included data on handheld technologies, e.g. last year (2005), 59% Howard Christensen, Publisher of us used cellphones, 16% used an IPod or other MP3 player, 8% used a Broadcast Dialogue 18 Turtle Path webcam, 7% used a personal digital assistant (PDA) and 3% used a Lagoon City ON L0K 1B0 BlackBerry. Still limited are the numbers who access the Internet from their (705) 484-0752 [email protected] cellphones or wireless devices, or use them for services other than their www.broadcastdialogue.com main purpose. Of the people who own a cellphone, BlackBerry or PDA, 7% use it to get news or weather information, 4% cent use it to get sports scores, 3% use it to take pictures or make videos and 2% use it to watch TV. Canadians listened to radio an average 19.1 hours a week in 2005, down slightly from 19.5 the year before. They watched an average of 25.1 hours of TV each week, up from 24.7 in 2004. Seventy-four per-cent of Canadian homes had a computer, and 78% of Canadians accessed the Internet in 2005, up from 71% and 76% respectively the year before. Other points included in the CRTC’s seventh Broadcasting Policy Monitoring Report include: RADIO – 913 English-language stations out of 1,223 radio services – 275 are French-language and 35 are third- language. -

The Aftermath of the Porn Rock Wars

Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review Volume 7 Number 2 Article 1 3-1-1987 Radio-Active Fallout and an Uneasy Truce - The Aftermath of the Porn Rock Wars Jonathan Michael Roldan Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jonathan Michael Roldan, Radio-Active Fallout and an Uneasy Truce - The Aftermath of the Porn Rock Wars, 7 Loy. L.A. Ent. L. Rev. 217 (1987). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr/vol7/iss2/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RADIO-ACTIVE FALLOUT AND AN UNEASY TRUCE-THE AFTERMATH OF THE PORN ROCK WARS Jonathan Michael Roldan * "Temperatures rise inside my sugar walls." - Sheena Easton from the song "Sugar Walls."' "Tight action, rear traction so hot you blow me away... I want a piece of your action." - M6tley Criie from the album Shout at the Devil.2 "I'm a fairly with-it person, but this stuff is curling my hair." - Tipper Gore, parent.3 "Fundamentalist frogwash." - Frank Zappa, musician.4 I. OVERTURE TO CONFLICT It began as an innocent listening of Prince's award-winning album, "Purple Rain,"5 and climaxed with heated testimony before the Senate Committee on Commerce in September 1985.6 In the interim the phrase "cleaning up the air" took on new dimensions as one group of parents * B.A., Journalism/Political Science, Cal. -

Annual Report 2000

CORUS AT A GLANCE OPERATING DIVISIONS KEY STATISTICS KEY BRANDS Radio Broadcasting With 49 stations (subject to CRTC approval of • Canadians spend 85.3 million hours tuned 43.50 the Metromedia acquisition) across the country, in to Corus radio stations each week August 31, 2000 including market clusters in high-growth urban • Corus radio stations reach 8.4 million centres in British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Canadians each week – 3 million more eports year-to-date eports year-to-date Ontario and Quebec, Corus Entertainment is than the closest competitor eports year-to-date Canada’s largest radio operator in terms of • Corus has the only private radio network revenue and audience tuning. covering major markets in Canada Corus announces purchase Corus announces • www.edge102.com is the ninth most listened the of purchase Corus completes the to Web site in the world Corus announces joint venture with CBC to venture joint Corus announces Corus announces that Liberty Media to that Liberty Media Corus announces Specialty Programming Corus Entertainment has control or an interest • Corus’ programming services in aggregate for with Torstar partnership eh.com – Corus announces in many of Canada’s leading specialty and pay- have 22 million subscribers THIRD QUARTER RESULTS – Corus r RESULTSTHIRD QUARTER Corus – 65% of increase profit operating SOUND PRODUCTS LTD.SOUND PRODUCTS – radio the purchase to CRTC GRANTS APPROVAL Corus for WIC assets of television premium and POWER BROADCASTING – assets Broadcasting Power TSE TSE 300 INDEX added is Corus -

Boom Radio Online

1 / 2 Boom Radio Online ... THRILL ME, KISS ME, KILL ME U2 ISLAND/ATLANTIC BOOM BOOM BOOM ... the streets or the commercial, radio-friendly style of the likes of Baby D (Billboard, ... Live sets now seamlessly blend electrifying material from the Nixons' debut .... Share this story · More Business News Stories · Top Stories · Postcard from Titanic's radio operator being sold at auction · Cicilline raises $650K for .... Boom will initially be on DAB in London, Bristol, Birmingham and Glasgow and nationally online across the UK. Debbie Marshall, Silver Travel .... LCCC Boom Radio. 1005 N. Abbe Road Elyria OH 44035 (440) 366-4801 (440) 366-4765 Fax http://www.lcccradio.com/ Send Email. Categories: Bands/Live .... Log Boom Radio students will report live on Seafair races.. The station will also be accessible across the UK online, and via smart speakers and apps. Boom Radio is founded by Phil Riley and David Lloyd, who have .... Britain's newest radio station is now on air - and proves that the old ones really are the best.. boom 99.7. Listen. LENNY KRAVITZ. ARE YOU GONNA GO MY WAY. Get it on iTunes. Menu. boom 99.7 boom 99.7 ... App Store · Play Store · LISTEN LIVE .... Stream Bloomberg Audio online for free. Get global business and financial news covering the top companies, industries and more 24 hours a day. est. 1999 designboom is the first and most popular digital magazine for architecture & design culture. daily news for a professional and creative audience.. Boom 93 je prvi i vodeći nezavisni elektronski medij u Požarevcu.. LIL WAYNE (MOSLEY/ZONE 4/INTERSCOPE) BOOM BOOM POW .. -

Shaw Direct "Digital Favourites" Programming

SHAW DIRECT "DIGITAL FAVOURITES" PROGRAMMING PACKAGE 62.61 CDN per month plus tax Updated October 1, 2012 Subject to Change 111.1/Anik F2 channels underlined New customers will only receive local Canadian TV channels from their area. A new TIME SHIFT BUNDLE option for 5.04 per month will provide all local channels listed here, including an East and West Coast U.S. standard and high-definition package. Indicated by T HD Channels in Green 379 82 KING-NBC Seattle T 820 287 Radio France International 244 380 SRC-East HD (F) 380 83 KOMO-ABC Seattle T 824 547 CKST-1040 Vancouver 245 381 TVA-East HD (F) 381 84 KIRO-CBS Seattle T 825 288 AMI Audio 248 388 V-East HD (F) 382 85 KCPQ-FOX Seattle T 826 490 CIUT-89.5 Toronto 252 304 CITY-TV Toronto HD 383 86 KCTS-PBS Seattle T 827 491 CHIN-1540 Toronto 253 337 NAT GEO WILD HD 384 74 CHMI-CITY Winnipeg T 828 492 CKUA-94.9 Edmonton 256 303 Global-Toronto HD 388 81 WNED-PBS Buffalo T 829 493 KDRK-93.7 Spokane 257 331 CNN-HD 389 8 CIVI-CTV 2 Victoria T 830 494 KZBD-105.7 Spokane 275 363 SPACE-HD 390 92 CBC NEWS NETWORK 831 495 KISC-98.1 Spokane 276 340 NAT GEO-HD 391 93 CTV NEWS CHANNEL 832 496 KMBI-107.9 Spokane 277 341 SHOWCASE-East HD 392 94 SHOP-Shopping Channel 833 497 KPBX-91.1 Spokane 284 320 WDIV/NBC-Detroit HD T 393 290 B.C. -

Benbella Spring 2020 Titles

Letter from the publisher HELLO THERE! DEAR READER, 1 We’ve all heard the same advice when it comes to dieting: no late-night food. It’s one of the few pieces of con- ventional wisdom that most diets have in common. But as it turns out, science doesn’t actually support that claim. In Always Eat After 7 PM, nutritionist and bestselling author Joel Marion comes bearing good news for nighttime indulgers: eating big in the evening when we’re naturally hungriest can actually help us lose weight and keep it off for good. He’s one of the most divisive figures in journalism today, hailed as “the Walter Cronkite of his era” by some and deemed “the country’s reigning mischief-maker” by others, credited with everything from Bill Clinton’s impeachment to the election of Donald Trump. But beyond the splashy headlines, little is known about Matt Drudge, the notoriously reclusive journalist behind The Drudge Report, nor has anyone really stopped to analyze the outlet’s far-reaching influence on society and mainstream journalism—until now. In The Drudge Revolution, investigative journalist Matthew Lysiak offers never-reported insights in this definitive portrait of one of the most powerful men in media. We know that worldwide, we are sick. And we’re largely sick with ailments once considered rare, including cancer, diabetes, and Alzheimer’s disease. What we’re just beginning to understand is that one common root cause links all of these issues: insulin resistance. Over half of all adults in the United States are insulin resistant, with other countries either worse or not far behind. -

À Montréal, Le 18 Avril 2019 Monsieur Claude Doucet Secrétaire Général

À Montréal, le 18 avril 2019 Monsieur Claude Doucet Secrétaire général CRTC Ottawa (Ontario) K1A 0N2 PAR LE FORMULAIRE DU CRTC PAR COURRIEL : [email protected] Objet : Demande de Sirius XM Canada Inc. en vue de renouveler la licence de radiodiffusion des entreprises nationales de radio par satellite par abonnement Sirius Canada et XM Canada qui expire le 31 août 2019 (Avis de consultation de radiodiffusion CRTC 2019-72) Monsieur le Secrétaire général, 1. L’ADISQ, dont les membres sont responsables de plus de 95 % de la production de disques, de spectacles et de vidéoclips d’artistes canadiens d’expression francophone, désire par la présente se prononcer sur la demande présentée par Sirius XM Canada Inc. (ci-après nommé Sirius XM) en vue de renouveler la licence de radiodiffusion des entreprises nationales de radio par satellite par abonnement Sirius Canada et XM Canada qui expire le 31 août 2019. 2. Les entreprises membres de l’ADISQ œuvrent dans tous les secteurs de la production de disques, de spectacles et de vidéos. On y retrouve des producteurs de disques, de spectacles et de vidéos, des maisons de disques, des gérants d’artistes, des distributeurs de disques, des maisons d’édition, des agences de spectacles, des salles et diffuseurs de spectacles, des agences de promotion et de relations de presse. 3. Sous réserve des modifications proposées dans le présent mémoire, l’ADISQ appuie ce renouvellement de licence. Toutefois, en raison de la situation de non-conformité observée par le Conseil au cours de la dernière période de licence nous estimons que ce renouvellement devrait être accordée pour une période écourtée de 5 ans. -

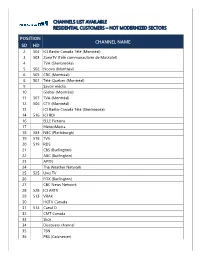

Channels List Available Residential

CHANNELS LIST AVAILABLE RESIDENTIAL CUSTOMERS – NOT MODERNIZED SECTORS POSITION CHANNEL NAME SD HD 2 504 ICI Radio-Canada Télé (Montréal) 3 503 ZoneTV (Télé communautaire de Maskatel) 4 TVA (Sherbrooke) 5 502 Noovo (Montréal) 6 505 CBC (Montréal) 8 501 Télé-Québec (Montréal) 9 Savoir média 10 Global (Montréal) 11 507 TVA (Montréal) 12 506 CTV (Montréal) 13 ICI Radio-Canada Télé (Sherbrooke) 14 516 ICI RDI 16 ELLE Fictions 17 MétéoMédia 18 583 NBC (Plattsburgh) 19 518 TV5 20 519 RDS 21 CBS (Burlington) 22 ABC (Burlington) 23 APTN 24 The Weather Network 25 525 Unis TV 26 FOX (Burlington) 27 CBC News Network 28 528 ICI ARTV 29 513 VRAK 30 HGTV Canada 31 514 Canal D 32 CMT Canada 33 Slice 34 Discovery channel 35 TSN 36 PBS (Colchester) 37 MAX 38 510 Canal Vie 39 508 LCN 40 Télétoon Français 41 Showcase 42 542 Télémag Québec 43 511 Historia 44 Évasion 45 515 Z télé 46 512 Séries Plus 47 CPAC Français 48 CPAC Anglais 50 BNN Bloomberg 52 552 ICI Explora 54 Assemblée Nationale du Québec 55 AMI-tv 56 AMI-télé 61 ICI Radio-Canada Télé (Québec) 64 TVA (Québec) 66 536 CASA 68 Citytv (Montréal) 75 PLANÈTE+ 78 MTV 79 Wild Pursuit Network 81 CBS (Seattle) 82 ABC (Seattle) 83 PBS (Seattle) 86 FOX (Seattle) 88 NBC (Seattle) 89 Télémagino 90 La Chaîne Disney 91 Yoopa 93 509 AddikTV 94 594 Investigation 95 Prise 2 97 MOI ET CIE 98 538 TVA Sports 99 RDS Info 100 539 RDS 2 101 YTV 102 CTV News Channel 103 Much Music 106 CTV Sci-Fi Channel 107 Vision TV 108 Teletoon Anglais 109 CTV Drama Channel 110 Fox Sports Racing 111 WGN (Chicago) 112 567 Sportsnet 360 -

Nurturing Media Vitality in Quebec's English-Speaking Minority

Brief to the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage Nurturing Media Vitality in Quebec’s English-speaking Minority Communities Presented by the Quebec Community Groups Network April 12, 2016 Introduction The Quebec Community Groups Network, or QCGN, is a not-for-profit representative organization. We serve as a centre of evidence-based expertise and collective action. QCGN is focused on strategic issues affecting the development and vitality of Canada’s English linguistic minority communities, to which we collectively refer as the English-speaking community of Quebec. Our 48 members are also not-for-profit community groups. Most provide direct services to community members. Some work regionally, providing broad-based services. Others work across Quebec in specific sectors such as health, and arts and culture. Our members include the Quebec Community Newspaper Association (QCNA). English-speaking Quebec is Canada’s largest official language minority community. A little more than 1 million Quebecers specify English as their first official spoken language. Although 84 per cent of our community lives within the Montreal Census Metropolitan Area, more than 210,000 community members live in other Quebec regions. Media Landscape English-speaking Quebecers have consistently signalled that access to information in their own language is both a need and a priority (CHSSN-CROP survey, various years). This may seem a bit of a contradiction in a world awash in English language information through CNN, Time magazine and Hollywood movies galore. The important nuance is that English- speaking Quebecers need information in their own language about their own local and regional communities, something that is increasingly hard to access on a consistent basis in a context of the francization of daily life in Quebec and the demise of traditional community media. -

Clear Channel and the Public Airwaves Dorothy Kidd University of San Francisco, [email protected]

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Media Studies College of Arts and Sciences 2005 Clear Channel and the Public Airwaves Dorothy Kidd University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.usfca.edu/ms Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Kidd, D. (2005). Clear channel and the public airwaves. In E. Cohen (Ed.), News incorporated (pp. 267-285). New York: Prometheus Books. Copyright © 2005 by Elliot D. Cohen. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts and Sciences at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Media Studies by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 13 CLEAR CHANNEL AND THE PUBLIC AIRWAVES DOROTHY KIDD UNIVERSITY OF SAN FRANCISCO With research assistance from Francisco McGee and Danielle Fairbairn Department of Media Studies, University of San Francisco DOROTHY KIDD, a professor of media studies at the University of San Francisco, has worked extensively in community radio and television. In 2002 Project Censored voted her article "Legal Project to Challenge Media Monopoly " No. 1 on its Top 25 Censored News Stories list. Pub lishing widely in the area of community media, her research has focused on the emerging media democracy movement. INTRODUCTION or a company with close ties to the Bush family, and a Wal-mart-like F approach to culture, Clear Channel Communications has provided a surprising boost to the latest wave of a US media democratization movement.