Extract from Hansard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Western Australia State Election 2017

RESEARCH PAPER SERIES, 2017–18 18 SEPTEMBER 2017 Western Australia state election 2017 Rob Lundie Politics and Public Administration Section Contents Introduction ................................................................................................ 2 Background ................................................................................................. 2 Electoral changes ................................................................................................ 2 2013 election ...................................................................................................... 2 Party leaders ....................................................................................................... 3 Aftermath for the WA Liberal Party ................................................................... 5 The campaign .............................................................................................. 5 Economic issues .................................................................................................. 5 Liberal/Nationals differences ............................................................................. 6 Transport ............................................................................................................ 7 Federal issues ..................................................................................................... 7 Party campaign launches .................................................................................... 7 Leaders debate .................................................................................................. -

P4793c-4801A Mrs Liza Harvey; Ms Mia Davies; Mr Bill Marmion; Mr Peter Katsambanis

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Wednesday, 12 August 2020] p4793c-4801a Mrs Liza Harvey; Ms Mia Davies; Mr Bill Marmion; Mr Peter Katsambanis IRON ORE PROCESSING (MINERALOGY PTY. LTD.) AGREEMENT AMENDMENT BILL 2020 Second Reading Resumed from an earlier stage of the sitting. MRS L.M. HARVEY (Scarborough — Leader of the Opposition) [2.56 pm]: I rise to continue my remarks about this amending legislation. I put on the record once again that the position of the Liberal Party room was a consensus position to not oppose this legislation. I would like to get on the record that we do not support the actions of Clive Palmer, which is why we are not opposing this legislation. During question time, I asked the Premier whether he would support a short sharp committee inquiry. It is ridiculous to say that the suggestion of a committee inquiry or that contentious legislation go to a committee to potentially strengthen it is in any way, shape or form showing that the legislation is not supported. That is ridiculous. The amending legislation in front of us is backdated to have effect from 11 August. It was read in just after 5.00 pm yesterday so that Mr Palmer and his lawyers could not get wind of it and could not lodge a writ in court. It needed to be read in yesterday after that opportunity had lapsed. The legislation is backdated to be effective from yesterday, 11 August 2020, at around about 5.00 pm. Should the upper house choose to send it to a committee to potentially strengthen it and ward off a potential High Court challenge, it could be done and dusted by 15 September. -

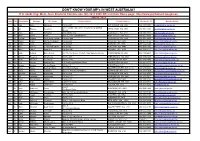

DON't KNOW YOUR MP's in WEST AUSTRALIA? If in Doubt Ring: West

DON'T KNOW YOUR MP's IN WEST AUSTRALIA? If in doubt ring: West. Aust. Electoral Commission (08) 9214 0400 OR visit their Home page: http://www.parliament.wa.gov.au HOUSE : MLA Hon. Title First Name Surname Electorate Postal address Postal Address Electorate Tel Member Email Ms Lisa Baker Maylands PO Box 907 INGLEWOOD WA 6932 (08) 9370 3550 [email protected] Unit 1 Druid's Hall, Corner of Durlacher & Sanford Mr Ian Blayney Geraldton GERALDTON WA 6530 (08) 9964 1640 [email protected] Streets Dr Tony Buti Armadale 2898 Albany Hwy KELMSCOTT WA 6111 (08) 9495 4877 [email protected] Mr John Carey Perth Suite 2, 448 Fitzgerald Street NORTH PERTH WA 6006 (08) 9227 8040 [email protected] Mr Vincent Catania North West Central PO Box 1000 CARNARVON WA 6701 (08) 9941 2999 [email protected] Mrs Robyn Clarke Murray-Wellington PO Box 668 PINJARRA WA 6208 (08) 9531 3155 [email protected] Hon Mr Roger Cook Kwinana PO Box 428 KWINANA WA 6966 (08) 6552 6500 [email protected] Hon Ms Mia Davies Central Wheatbelt PO Box 92 NORTHAM WA 6401 (08) 9041 1702 [email protected] Ms Josie Farrer Kimberley PO Box 1807 BROOME WA 6725 (08) 9192 3111 [email protected] Mr Mark Folkard Burns Beach Unit C6, Currambine Central, 1244 Marmion Avenue CURRAMBINE WA 6028 (08) 9305 4099 [email protected] Ms Janine Freeman Mirrabooka PO Box 669 MIRRABOOKA WA 6941 (08) 9345 2005 [email protected] Ms Emily Hamilton Joondalup PO Box 3478 JOONDALUP WA 6027 (08) 9300 3990 [email protected] Hon Mrs Liza Harvey Scarborough -

CENTRAL COUNTRY ZONE Minutes

CENTRAL COUNTRY ZONE Minutes Friday 25 June 2021 Quairading Town Hall Jennaberring Road, Quairading Commencing at 9.36am Central Country Zone Meeting 25 June 2021 Table of Contents 1.0 OPENING AND WELCOME ............................................................................... 3 1.1 Announcement by the Zone President, Cr Brett McGuinness, regarding COVID-19 Rules for the Meeting ................................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Vale Greg Hadlow ..................................................................................................................................... 3 1.3 Welcome – Cr Wayne Davies, President Shire of Quairading ............................................................. 4 1.4 Beverley Golf Day .................................................................................................................................... 4 1.5 Meeting Etiquette ..................................................................................................................................... 4 2.0 ATTENDANCE AND APOLOGIES ..................................................................... 4 3.0 DECLARATION OF INTEREST ......................................................................... 6 4.0 MINUTES ............................................................................................................ 7 4.1 Confirmation of Minutes from the Zone Meeting held Friday 23 April 2021 (Attachment) -

WA Ministerial Arrangements Further Information

Barton Deakin Brief: WA Ministry 26 September 2016 The Premier of Western Australia, the Hon Colin Barnett MLA, has announced several changes to the WA Ministry. These changes were required after the resignation of two former ministers, Minister for Agriculture and Food and Minister for Transport, Hon Dean Nalder MLA and the Minister for Minister for Local Government, Minister for Community Services, Minister for Seniors and Volunteering, and Minister for Youth, the Hon Tony Simpson MLA. WA Ministerial Arrangements The changes to the WA Ministry are outlined below: The Hon Mark Lewis MLC, Member of the Legislative Council for Mining and Pastoral Region, is the new Minister for Agriculture and Food; The Hon Paul Miles MLA, Member for North Metropolitan Region, is the new Minister for Local Government in addition to his existing role as Minister for Community Services, Minister for Seniors and Volunteering and Minister for Youth; The Hon Bill Marmion MLA, in addition to his role as Minister for State Development and Innovation, adds Transport; The Hon Sean L’Estrange MLA retains the Mines and Petroleum as well as Small Business and adds Finance. The new Ministers were sworn into their new positions by the Governor of Western Australia, HE the Hon Kerry Sanderson AO on Friday. A full list of the WA Ministry is enclosed. The next WA State Election will be held on Saturday 11 March 2017. Further Information The media release from the Premier which summarises the changes to the WA Ministry can be read here. For more information please contact Eacham Curry on +61 428 933 130 or Jessica Yu on +61 2 9191 7888. -

Role of Integrity Agencies Section 44 of the Constitution Parliaments And

Role of Integrity Agencies Section 44 of the Constitution Parliaments and Their Watchdogs Delegated Legislation and the Democratic Deficit SPRING / SUMMER 2017 Vol 32.2 AUSTRALASIAN PARLIAMENTARY REVIEW Table of Contents From the Editor .................................................................................................................. 3 Articles................................................................................................................................. 4 Section 44 of the Constitution – What Have We Learnt and What Problems Do We Still Face? Anne Twomey ........................................................................................................... 5 Purity of Election: Foreign Allegiance and Membership of the Parliament of New South Wales Mel Keenan ............................................................................................................ 22 Delegated Legislation and the Democratic Deficit: The Case of Christmas Island Kelvin Matthews ...................................................................................................... 32 The Western Australian Parliament’s Relationship with the Executive: Recent Executive Actions and Their Impact on the Ability of Parliamentary Committees to Undertake Scrutiny Alex Hickman .......................................................................................................... 39 Developing an Ethical Culture in Public Sector Governance: The Role of Integrity Agencies Chris Aulich and Roger Wettenhall ......................................................................... -

M EMBER E LECTORATE C ONTACT DETAILS Hon

M EMBER E LECTORATE C ONTACT DETAILS Hon. Peter Bruce Watson MLA PO Box 5844 Albany 6332 Ph: 9841 8799 Albany Speaker Email: [email protected] Party: ALP Dr Antonio (Tony) De 2898 Albany Highway Paulo Buti MLA Kelmscott WA 6111 Party: ALP Armadale Ph: (08) 9495 4877 Email: [email protected] Website: https://antoniobuti.com/ Mr David Robert Michael MLA Suite 3 36 Cedric Street Stirling WA 6021 Balcatta Government Whip Ph: (08) 9207 1538 Party: ALP Email: [email protected] Mr Reece Raymond Whitby MLA P.O. Box 4107 Baldivis WA 6171 Ph: (08) 9523 2921 Parliamentary Secretary to the Email: [email protected] Treasurer; Minister for Finance; Aboriginal Affairs; Lands, and Baldivis Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Environment; Disability Services; Electoral Affairs Party: ALP Hon. David (Dave) 6 Old Perth Road Joseph Kelly MLA Bassendean WA 6054 Ph: 9279 9871 Minister for Water; Fisheries; Bassendean Email: [email protected] Forestry; Innovation and ICT; Science Party: ALP Mr Dean Cambell Nalder MLA P.O. Box 7084 Applecross North WA 6153 Ph: (08) 9316 1377 Shadow Treasurer ; Shadow Bateman Email: [email protected] Minister for Finance; Energy Party: LIB Ms Cassandra (Cassie) PO Box 268 Cloverdale 6985 Michelle Rowe MLA Belmont Ph: (08) 9277 6898 Party: ALP Email: [email protected] Mrs Lisa Margaret O'Malley MLA P.O. Box 272 Melville 6156 Party: ALP Bicton Ph: (08) 9316 0666 Email: [email protected] Mr Donald (Don) PO Box 528 Bunbury 6230 Thomas Punch MLA Bunbury Ph: (08) 9791 3636 Party: ALP Email: [email protected] Mr Mark James Folkard MLA Unit C6 Currambine Central Party: ALP 1244 Marmion Avenue Burns Beach Currambine WA 6028 Ph: (08) 9305 4099 Email: [email protected] Hon. -

P5768d-5775A Ms Mia Davies; Mr David Templeman; Dr Mike Nahan; Mr Vincent Catania; Mr Roger Cook; Mr Paul Papalia

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Thursday, 9 November 2017] p5768d-5775a Ms Mia Davies; Mr David Templeman; Dr Mike Nahan; Mr Vincent Catania; Mr Roger Cook; Mr Paul Papalia McGOWAN MINISTRY — CHINA AND JAPAN VISIT Standing Orders Suspension — Motion MS M.J. DAVIES (Central Wheatbelt — Leader of the National Party) [2.56 pm]: — without notice: I move — That so much of standing orders be suspended as is necessary to enable the following motion to be moved forthwith — That this house condemns the government for absenting four ministers on a parliamentary sitting day, thereby avoiding public scrutiny and diminishing the ability of the opposition to hold the government to account. I think we have seen today why there is a need for the government to agree to this motion. Absolute arrogance and contempt have been shown to this house today. Indeed, it has emerged over the past 16 weeks that this house has sat. Some examples of why we think this government needs to explain why, at its own instigation, it has arranged overseas travel — Mr D.J. Kelly interjected. The SPEAKER: Minister for Water, I call you to order for the first time. Mrs L.M. Harvey interjected. The SPEAKER: Member for Scarborough, you have one of your own side on her feet. Ms M.J. DAVIES: Why has this government, presumably signed off by the Premier, arranged overseas travel for a number of its ministers on a day that Parliament is sitting, and during question time? I understand that one of the ministers chose to wait until after question time was completed to join the Premier and other ministers. -

P7668b-7686A Mr Zak Kirkup; Ms Mia Davies; Dr Tony Buti; Amber-Jade Sanderson; Ms Janine Freeman; Ms Cassandra Rowe; Mr Terry Healy

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Tuesday, 10 November 2020] p7668b-7686a Mr Zak Kirkup; Ms Mia Davies; Dr Tony Buti; Amber-Jade Sanderson; Ms Janine Freeman; Ms Cassandra Rowe; Mr Terry Healy PUBLIC HEALTH AMENDMENT (SAFE ACCESS ZONES) BILL 2020 Second Reading Resumed from 14 October. MR Z.R.F. KIRKUP (Dawesville) [7.01 pm]: I rise to talk about the Public Health Amendment (Safe Access Zones) Bill 2020. At the outset, I indicate that the Liberal Party has resolved that its members will deal with this bill as a matter of conscience. As such, although I am the lead speaker for the party, there is obviously no resolved position for me to take the lead on. With that in mind, I rise to support the bill. This legislation will go some distance to make sure that we address the concerns raised in the consultation process with the Department of Health by people who have gone through a significant and lengthy campaign to implement safe access zones across Australia. Safe access zones were not necessarily something that I was familiar with when they were initially floated by the Minister for Health when he first spoke about this issue on 23 February 2018. Since then, I have read a significant number of reports, including those produced by the Department of Health. Marie Stopes Australia, the University of Queensland and the Australian Women Against Violence Alliance report titled “Safe Access Zones in Australia: Legislative Considerations” provided a comprehensive outline of the Australian context for safe access zones, exclusion zones or bubbles as they are sometimes called in different states and territories, and a good level of understanding of what that looks like in each respective state’s context. -

P3229b-3256A Mrs Liza Harvey

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Wednesday, 27 May 2020] p3229b-3256a Mrs Liza Harvey; Ms Libby Mettam; Mr Kyran O'Donnell; Mr Vincent Catania; Mr Dean Nalder; Dr David Honey; Mrs Alyssa Hayden; Mr Paul Papalia; Mr Roger Cook CORONAVIRUS — GOVERNMENT RESTRICTIONS Motion MRS L.M. HARVEY (Scarborough — Leader of the Opposition) [4.00 pm]: I move — That this house condemns the McGowan Labor government for its handling of the lifting of COVID-19 restrictions and causing unnecessary economic harm, small business closures and job losses. At the outset, I have no quarrel with the way this government, in conjunction with the national cabinet, has handled the health crisis around COVID-19. The way that the state Premiers and the Prime Minister have come together, along with all the health ministers, to put in place measures, a strategy and a response around managing the COVID-19 health crisis has been handled well. I want to be very clear and put that on the record. I believe the lockdown was necessary at the start, because we did not understand what we were dealing with, we did not understand quite how virulent COVID-19 would be and we needed a national stocktake of our health system, its capacity and what was going to be required should we have outbreaks of COVID-19. I am glad the Minister for Health is in the chamber to hear this. I think that the health response has been very good. We are now in a very good position in Western Australia and we have had hundreds of nurses trained to step up into intensive care units should we have an outbreak and require additional ICU beds to open. -

P4750c-4770A Dr Mike Nahan; Mr Dean Nalder

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Thursday, 12 October 2017] p4750c-4770a Dr Mike Nahan; Mr Dean Nalder; Acting Speaker; Mr Vincent Catania; Mr Sean L'Estrange; Mrs Liza Harvey; Ms Mia Davies; Mr Mark McGowan; Mr Matthew Hughes; Dr Tony Buti; Mr Colin Barnett SALARIES AND ALLOWANCES AMENDMENT (DEBT AND DEFICIT REMEDIATION) BILL 2017 Appropriations Message from the Governor received and read recommending appropriations for the bill. Second Reading Resumed from an earlier stage of the sitting. DR M.D. NAHAN (Riverton — Leader of the Opposition) [2.49 pm]: I will resume from where I left off. I would like to make a few comments about some of the issues that were raised in the question time just finished and in previous question times, and of course the rhetoric from the government that brought down the budget. Everyone recognises that the Labor Party is in a difficult financial situation. It went to an election in 2008, 2013 and 2017 with a massive increase in expenditure. In 2008, it thought it had it. In 2013 it was warned about iron ore prices, which it ignored, and came down with the mother of all expenses. It went to the 2017 election, committed to Metronet and a raft of other expenditure and put out a report to the public, not to Treasury—it avoided that—and said, “Here’s our plan. It’s fully funded. It’s all costed. We’ve got it all covered.” It said it could afford it and pay down debt like a mortgage. It said it could eliminate the deficit over the forward estimates, not increase any taxes or charges, not impose a gold royalty increase and keep electricity charges at the forward estimates price. -

FUTURE of WORK in AUSTRALIA Preparing for Tomorrow's World

BANKWEST CURTIN ECONOMICS CENTRE FUTURE OF WORK IN AUSTRALIA Preparing for tomorrow's world Report Launch - Program Friday 13 April 2018 from 7.15am to 9.00am Hyatt Regency Perth Grand Ballroom 99 Adelaide Terrace Perth #FutureOfWork @BankwestCurtin About the Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre The Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre is an independent economic and social research organisation located within the Curtin Business School at Curtin University. The Centre was established in 2012 through the generous support of Bankwest, a division of the Commonwealth Bank of Australia. The Centre’s core mission is to deliver high quality, accessible research that enhances our understanding of key economic and social issues that contribute to the wellbeing of West Australian families, businesses and communities. The Centre’s research and engagement activities are designed to influence economic and social policy debates in state and Federal Parliament, regional and national media, and the wider Australian community. Through high quality, evidence-based research and analysis, our research outcomes inform policy makers and commentators of the economic challenges to achieving sustainable and equitable growth and prosperity both in Western Australia and nationally. The Centre capitalises on Curtin University’s reputation for excellence in economic modelling, forecasting, public policy research, trade and industrial economics and spatial sciences. Centre researchers have specific expertise in economic forecasting, quantitative modelling and economic and social policy evaluation. Program 7:15am Registration 7:30am Welcome by MC Di Darmody 7.32am Welcome to Country by Robyn Collard and Wesley College 7.40am Introduction Scott Guerini Year-7 student, Telethon Ambassador Future of Work video 7:45am Opening Address Hon.