WRP RECOVERY PLAN Final 24022014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

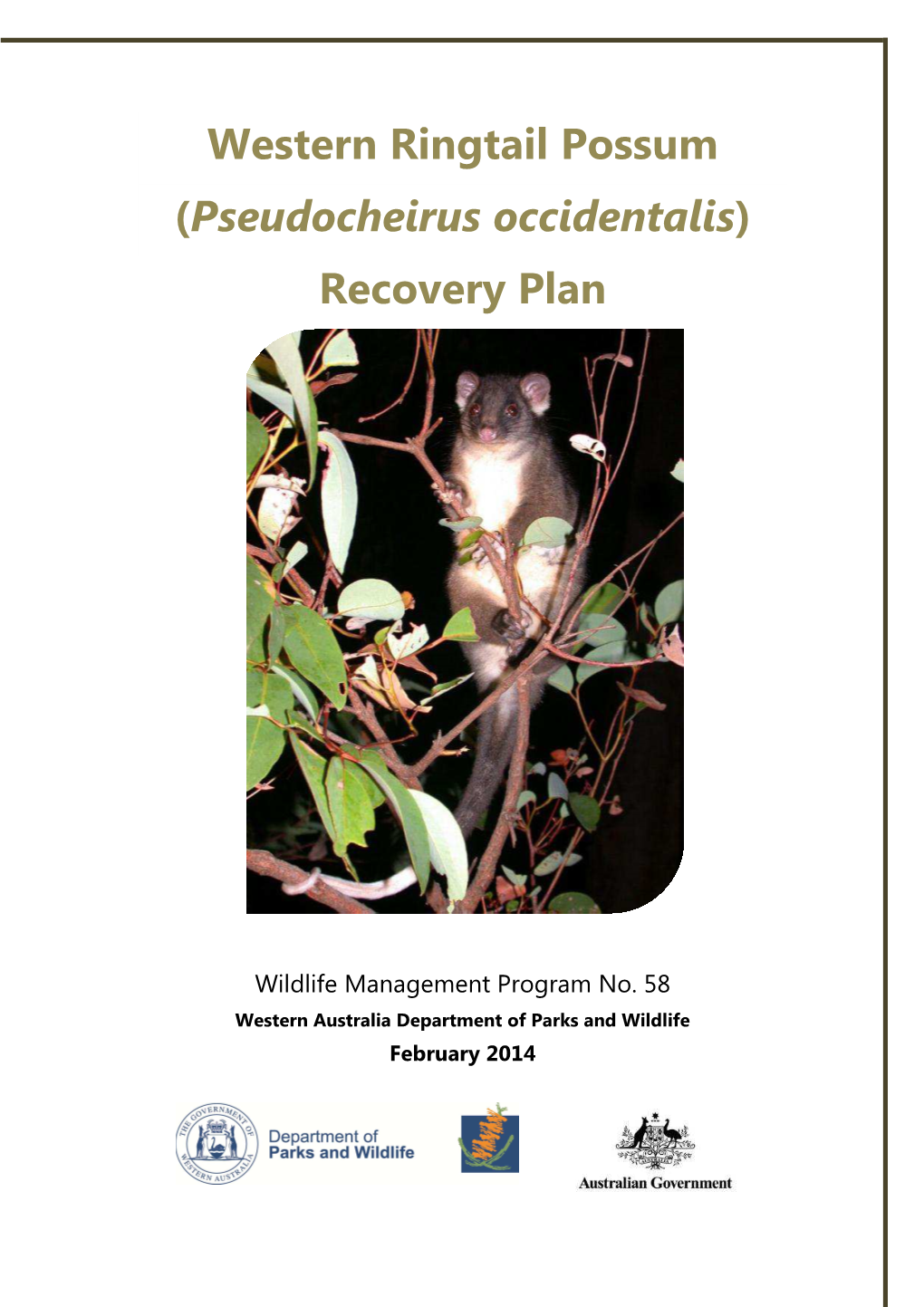

Western Ringtail Possum (Pseudocheirus Occidentalis) Recovery Plan

Western Ringtail Possum (Pseudocheirus occidentalis) Recovery Plan Wildlife Management Program No. 58 Western Australia Department of Parks and Wildlife October 2014 Wildlife Management Program No. 58 Western Ringtail Possum (Pseudocheirus occidentalis) Recovery Plan October 2014 Western Australia Department of Parks and Wildlife Locked Bag 104, Bentley Delivery Centre, Western Australia 6983 Foreword Recovery plans are developed within the framework laid down in Department of Parks and Wildlife Policy Statements Nos. 44 and 50 (CALM 1992, 1994), and the Australian Government Department of the Environment’s Recovery Planning Compliance Checklist for Legislative and Process Requirements (DEWHA 2008). Recovery plans outline the recovery actions that are needed to urgently address those threatening processes most affecting the ongoing survival of threatened taxa or ecological communities, and begin the recovery process. Recovery plans are a partnership between the Department of the Environment and the Department of Parks and Wildlife. The Department of Parks and Wildlife acknowledges the role of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 and the Department of the Environment in guiding the implementation of this recovery plan. The attainment of objectives and the provision of funds necessary to implement actions are subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. This recovery plan was approved by the Department of Parks and Wildlife, Western Australia. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in status of the taxon or ecological community, and the completion of recovery actions. Information in this recovery plan was accurate as of October 2014. -

Local Population Structure of a Naturally Occurring Metapopulation of the Quokka (Setonix Brachyurus Macropodidae: Marsupialia)

Biological Conservation 110 (2003) 343–355 www.elsevier.com/locate/biocon Local population structure of a naturally occurring metapopulation of the quokka (Setonix brachyurus Macropodidae: Marsupialia) Matt W. Haywarda,b,c,*, Paul J. de Toresb,c, Michael J. Dillonc, Barry J. Foxa aSchool of Biological, Earth and Environmental Science, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia bDepartment of Conservation and Land Management, Wildlife Research Centre, PO Box 51 Wanneroo, WA6946, Australia cDepartment of Conservation and Land Management, Dwellingup Research Centre, Banksiadale Road, Dwellingup, WA6213, Australia Received 8 May 2002; received in revised form 18 July 2002; accepted 22 July 2002 Abstract We investigated the population structure of the quokka (Setonix brachyurus) on the mainland of Western Australia using mark– recapture techniques. Seven previously known local populations and one unconfirmed site supporting the preferred, patchy and discrete, swampy habitat of the quokka were trapped. The quokka is now considered as locally extinct at three sites. The five remaining sites had extremely low numbers, ranging from 1 to 36 individuals. Population density at these sites ranged from 0.07 to 4.3 individuals per hectare. There has been no response to the on-going, 6 year fox control programme occurring in the region despite the quokkas’ high fecundity and this is due to low recruitment levels. The remaining quokka populations in the northern jarrah forest appear to be the terminal remnants of a collapsing metapopulation. # 2002 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Population structure; Predation; Reproduction; Setonix brachyurus; Vulnerable 1. Introduction The Rottnest Island quokka population fluctuates around 5000 with peaks of 10,000 individuals (Waring, The quokka (Setonix brachyurus Quoy & Gaimard 1956). -

Platypus Collins, L.R

AUSTRALIAN MAMMALS BIOLOGY AND CAPTIVE MANAGEMENT Stephen Jackson © CSIRO 2003 All rights reserved. Except under the conditions described in the Australian Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, duplicating or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. Contact CSIRO PUBLISHING for all permission requests. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Jackson, Stephen M. Australian mammals: Biology and captive management Bibliography. ISBN 0 643 06635 7. 1. Mammals – Australia. 2. Captive mammals. I. Title. 599.0994 Available from CSIRO PUBLISHING 150 Oxford Street (PO Box 1139) Collingwood VIC 3066 Australia Telephone: +61 3 9662 7666 Local call: 1300 788 000 (Australia only) Fax: +61 3 9662 7555 Email: [email protected] Web site: www.publish.csiro.au Cover photos courtesy Stephen Jackson, Esther Beaton and Nick Alexander Set in Minion and Optima Cover and text design by James Kelly Typeset by Desktop Concepts Pty Ltd Printed in Australia by Ligare REFERENCES reserved. Chapter 1 – Platypus Collins, L.R. (1973) Monotremes and Marsupials: A Reference for Zoological Institutions. Smithsonian Institution Press, rights Austin, M.A. (1997) A Practical Guide to the Successful Washington. All Handrearing of Tasmanian Marsupials. Regal Publications, Collins, G.H., Whittington, R.J. & Canfield, P.J. (1986) Melbourne. Theileria ornithorhynchi Mackerras, 1959 in the platypus, 2003. Beaven, M. (1997) Hand rearing of a juvenile platypus. Ornithorhynchus anatinus (Shaw). Journal of Wildlife Proceedings of the ASZK/ARAZPA Conference. 16–20 March. -

Translocations and Fauna Reconstruction Sites: Western Shield Review—February 2003

108 Conservation Science W. Aust. 5 (2) : 108–121P.R. Mawson (2004) Translocations and fauna reconstruction sites: Western Shield review—February 2003 PETER R. MAWSON1 1Senior Zoologist, Wildlife Branch , Department of Conservation and Land Management, Locked Bag 104 Bentley Delivery Centre WA 6983. [email protected] SUMMARY address this problem, but will result in slower progress towards future milestones for some species. The captive-breeding of western barred bandicoots Objectives has also been hampered by disease issues, but this problem is dealt with in more detail elsewhere in this edition (see The objectives of Western Shield with regard to fauna Morris et al. this issue). translocations were to re-introduce a range of native fauna There is a clear need to better define criteria that will species to a number of sites located primarily in the south- be used to determine the success or failure of translocation west of Western Australia. At some sites whole suites of programs, and for those same criteria to be included in fauna needed to be re-introduced, while at others only Recovery Plans and Interim Recovery Plans. one or a few species were targeted for re-introduction. A small number of the species that are currently the Integration of Western Shield activities with recovery subject of captive-breeding programs and or translocations actions and co-operative arrangements with community do not have Recovery Plans or Interim Recovery Plans, groups, wildlife carers, wildlife sanctuaries, Perth Zoo and contrary to CALM Policy Statement No. 50. In other educational outcomes were other key objectives. cases the priorities by which plans are written does not Achievements reflect the IUCN rank assigned those species by the Western Australian Threatened Species Scientific The fauna translocation objectives defined in the founding Committee. -

The Western Ringtail Possum (Pseudocheirus Occidentalis)

A major road and an artificial waterway are barriers to the rapidly declining western ringtail possum, Pseudocheirus occidentalis Kaori Yokochi BSc. (Hons.) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Animal Biology Faculty of Science October 2015 Abstract Roads are known to pose negative impacts on wildlife by causing direct mortality, habitat destruction and habitat fragmentation. Other kinds of artificial linear structures, such as railways, powerline corridors and artificial waterways, have the potential to cause similar negative impacts. However, their impacts have been rarely studied, especially on arboreal species even though these animals are thought to be highly vulnerable to the effects of habitat fragmentation due to their fidelity to canopies. In this thesis, I studied the effects of a major road and an artificial waterway on movements and genetics of an endangered arboreal species, the western ringtail possum (Pseudocheirus occidentalis). Despite their endangered status and recent dramatic decline, not a lot is known about this species mainly because of the difficulties in capturing them. Using a specially designed dart gun, I captured and radio tracked possums over three consecutive years to study their movement and survival along Caves Road and an artificial waterway near Busselton, Western Australia. I studied the home ranges, dispersal pattern, genetic diversity and survival, and performed population viability analyses on a population with one of the highest known densities of P. occidentalis. I also carried out simulations to investigate the consequences of removing the main causes of mortality in radio collared adults, fox predation and road mortality, in order to identify effective management options. -

Woylie Or Brush-Tailed Bettong

Woylie Bettongia penicillata ogilbyi Conservation Status: Critically Endangered Identification The brush-tailed bettong Bettongia penicillata is a small kangaroo-like marsupial that was once found throughout much of mainland Australia. The subspecies Bettongia penicillata penicillata, endemic to south-eastern Australia, is considered extinct. Bettongia penicillata ogilbyi, commonly known as the woylie, is the only surviving subspecies and is found in the south- west of Western Australia. Photos: M. Bundock (left); R. McLean (right) Woylies have yellowish grey to reddish brown fur with a pale belly and a long, prehensile tail with a black brush at the end. They have strongly clawed forefeet, used for digging for food and nest making. They move about using all four legs and sometimes also their tail when foraging, but when flushed, they will bound extremely fast on their back legs with the head held low, back arched and tail almost straight. Head and body length: 280-365mm Tail length: 250-360mm Weight: 745-1850g Taxonomy Family: Potoroidae Genus: Bettongia Species: penicillata Subspecies: ogilbyi Other common names: brush-tailed bettong, brush-tailed rat-kangaroo Distribution and Habitat Brush-tailed bettongs were found across most of southern and central Australia prior to European settlement and the introduction of feral cats and foxes. The woylie is endemic to the south-west of WA but they are now only known from two areas: Upper Warren and Dryandra Woodlands. There are also translocated populations at Batalling, and inside fenced areas in Mt Gibson, Karakamia and Whiteman Park and also in New South Wales and South Australia, and on islands in SA. -

Viruses of the Common Brushtail Possum

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. Viruses of the common brushtail possum (Trichosurus vulpecula) Matthew Robert Finch Perrott A thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Veterinary Science. Massey University 1998. 11 Abstract A tissue culture survey was conducted to detect viruses in possums. Up to 14 tissues from93 wild caught possums were inoculated (co-cultivation) onto three marsupial cell lines. Possum primary cell cultivation was also developed throughout the survey period and together these procedures sought to detect viral infections as overt clinical disease, as unapparent illnesses or present in a latent form. Three passages of seven days duration were routinely performed. Haemadsorption tests (chick, guinea pig and human " 0 " RBCs at 37°C) and examination ofstained monolayers (chamber slides) were completed forthe third passage. A few adenovirus-like particles were identified by electron microscopy in one of two possums' tissue cultures in which a non-sustainable cytopathic effect was detected. No haemadsorption or abnormal chamber slide cytology was demonstrated. Adenoviruses were identified by electron microscopy in faecal or intestinal contents samples fromfo ur of the survey possums. Wobbly possum disease (WPD), a newly described neurological disease of possums, was suggested to have a viral aetiology when filtered infecrious material (clarifiedspleen suspension froma confirmed case ofWPD passed through a 0.22 /lmmembrane) could transmit disease to susceptible possums following intra-peritoneal inoculation. -

Common Brushtail Possum

Our Wildlife Factsheet Common Brushtail Possum The Common Brushtail Possum is the most abundant and familiar of the Australian possums. Scientific name Trichosurus vulpecula Did you know? A nocturnal animal, it spends the day in a den in a hollow branch, tree-trunk, fallen log, rock cavity or even a hollow termite mound. Brushtail Possums prefer to live by themselves, not with other possums. The Brushtail Possum moves rapidly among trees and will leap from one branch to another. Figure 1. Common Brushtail Possum © I. McCann DSE 2008 Brushtail Possums use a range of sounds including screams, hissing and growling which are frequent, Diet particularly in mating season. Brushtail Possums eat plant material, supplemented Studies of the behaviour of Brushtail Possums have with bird eggs, baby birds and some insects. They shown that about 16 per cent of their time is spent mainly eat leaves of eucalypts but also some shrubs feeding, 30 per cent travelling, 44 per cent sleeping or (mainly wattles), herbs, flowers and fruit. They forage in sheltering, and 10 per cent grooming. the canopy, in lower levels of the forest and on the ground. In urban areas, the Common Brushtail Possum In New Zealand, where it was introduced, the Brushtail will eat a variety of food including fruit and bread. Possum is a pest, however people use its fur for a wide The Brushtail Possum’s liver cannot cope with an range of products including socks and jumpers. abundance of toxins in eucalypt leaves so they need to have a varied diet. Description The Brushtail Possum’s head and body length is 35 -55 Brushtail Possums prefer eucalyptus leaves with a high cm and its tail is from 25 - 40 cm long. -

Sugarloaf Pipeline Project Toolangi Habitat Linkage Monitoring Effectiveness of Glider Pole Linkages May 2017

Melbourne Water Corporation Sugarloaf Pipeline Project Toolangi Habitat Linkage Monitoring Effectiveness of Glider Pole Linkages May 2017 Acknowledgements The following individuals or groups have assisted in the preparation of this report. However, it is acknowledged that the contents and views expressed within this report are those of GHD Pty Ltd and do not necessarily reflect the views of the parties acknowledged below: The Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) for allowing access to records in the VBA database Melbourne Water Corporation staff including Andrea Burns, Paul Evans, Alex Sneskov, Anna Zsoldos, Mark Scida, Warren Tomlinson and Steve McGill for providing assistance, support and advice throughout the project GHD | Report for Melbourne Water Corporation - Sugarloaf Pipeline Project Toolangi Habitat Linkage Monitoring, 31/29843 | i Abbreviations DELWP Victorian Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (formerly DEPI) DEPI Victorian Department of Environment and Primary Industries (now DELWP) DSE Department of Sustainability and Environment (now DELWP) EPBC Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 EVC Ecological Vegetation Class EWP Elevated Work Platform FFG Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 GHD GHD Pty Ltd ROW Right of Way MW Melbourne Water Corporation Spp. More than one species TSF Toolangi State Forest ii | GHD | Report for Melbourne Water Corporation - Sugarloaf Pipeline Project Toolangi Habitat Linkage Monitoring, 31/29843 Table of contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................................. -

Numbat (Myrmecobius Fasciatus) Recovery Plan

Numbat (Myrmecobius fasciatus) Recovery Plan Wildlife Management Program No. 60 Western Australia Department of Parks and Wildlife February 2017 Wildlife Management Program No. 60 Numbat (Myrmecobius fasciatus) Recovery Plan February 2017 Western Australia Department of Parks and Wildlife Locked Bag 104, Bentley Delivery Centre, Western Australia 6983 Foreword Recovery plans are developed within the framework laid down in Department of Parks and Wildlife Corporate Policy Statement No. 35; Conserving Threatened and Ecological Communities (DPaW 2015a), Corporate Guidelines No. 35; Listing and Recovering Threatened Species and Ecological Communities (DPaW 2015b), and the Australian Government Department of the Environment’s Recovery Planning Compliance Checklist for Legislative and Process Requirements (Department of the Environment 2014). Recovery plans outline the recovery actions that are needed to urgently address those threatening processes most affecting the ongoing survival of threatened taxa or ecological communities, and begin the recovery process. Recovery plans are a partnership between the Department of the Environment and Energy and the Department of Parks and Wildlife. The Department of Parks and Wildlife acknowledges the role of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 and the Department of the Environment and Energy in guiding the implementation of this recovery plan. The attainment of objectives and the provision of funds necessary to implement actions are subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. This recovery plan was approved by the Department of Parks and Wildlife, Western Australia. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in status of the taxon or ecological community, and the completion of recovery actions. -

Mammals of the Avon Region

Mammals of the Avon Region By Mandy Bamford, Rowan Inglis and Katie Watson Foreword by Dr. Tony Friend R N V E M E O N G T E O H F T W A E I S L T A E R R N A U S T 1 2 Contents Foreword 6 Introduction 8 Fauna conservation rankings 25 Species name Common name Family Status Page Tachyglossus aculeatus Short-beaked echidna Tachyglossidae not listed 28 Dasyurus geoffroii Chuditch Dasyuridae vulnerable 30 Phascogale calura Red-tailed phascogale Dasyuridae endangered 32 phascogale tapoatafa Brush-tailed phascogale Dasyuridae vulnerable 34 Ningaui yvonnae Southern ningaui Dasyuridae not listed 36 Antechinomys laniger Kultarr Dasyuridae not listed 38 Sminthopsis crassicaudata Fat-tailed dunnart Dasyuridae not listed 40 Sminthopsis dolichura Little long-tailed dunnart Dasyuridae not listed 42 Sminthopsis gilberti Gilbert’s dunnart Dasyuridae not listed 44 Sminthopsis granulipes White-tailed dunnart Dasyuridae not listed 46 Myrmecobius fasciatus Numbat Myrmecobiidae vulnerable 48 Chaeropus ecaudatus Pig-footed bandicoot Peramelinae presumed extinct 50 Isoodon obesulus Quenda Peramelinae priority 5 52 Species name Common name Family Status Page Perameles bougainville Western-barred bandicoot Peramelinae endangered 54 Macrotis lagotis Bilby Peramelinae vulnerable 56 Cercartetus concinnus Western pygmy possum Burramyidae not listed 58 Tarsipes rostratus Honey possum Tarsipedoidea not listed 60 Trichosurus vulpecula Common brushtail possum Phalangeridae not listed 62 Bettongia lesueur Burrowing bettong Potoroidae vulnerable 64 Potorous platyops Broad-faced -

(Bettongia Penicillata) in Australia

The population and epidemiological dynamics associated with recent decline of woylies (Bettongia penicillata) in Australia. Carlo Pacioni DVM, MVS (Cons Med) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University, 2010 Printed on recycled paper Photo: Sabrina Trocini To my wife and friend, Sabrina I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work, which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. ……………..………………………………………………. Carlo Pacioni I Preface Chapters 5, 6, 7 and 8 are either published papers or manuscripts intended for publication in scientific journals as stand‐alone pieces of work. Consequently, some repetition was unavoidable. In addition, some differences in style are due to the requirements of the targeted journal. The reference style of the remaining chapters follows the current guidelines for the journal of Conservation Biology. The intellectual development and writing of this thesis was carried out by the author. Inclusion of co‐authors in the papers is to acknowledge the contributions of collaborators who provided tissue samples, demographic data, preliminary analysis and/or background information, as well as helpful discussions and editorial comments. II Abstract The woylie or brush‐tailed bettong (Bettongia penicillata ogilbyi) has recently undergone a dramatic decline (approximately 80% between 2001 and 2006). The Woylie Conservation and Research Project (WCRP) was established to investigate possible causes of this decline. It was hypothesised that predators and/or a disease may be a concomitant cause if not the primary cause(s) of the decline, based on the peculiar temporal and spatial characteristics of the decline and available associative evidence.