Customary Law Principles As a Tool for Human Rights Advocacy: Innovating Nigerian Customary Practices Using Lessons from Ugandan and South African Courts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ph.D Thesis-A. Omaka; Mcmaster University-History

MERCY ANGELS: THE JOINT CHURCH AID AND THE HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE IN BIAFRA, 1967-1970 BY ARUA OKO OMAKA, BA, MA A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Ph.D. Thesis – A. Omaka; McMaster University – History McMaster University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2014), Hamilton, Ontario (History) TITLE: Mercy Angels: The Joint Church Aid and the Humanitarian Response in Biafra, 1967-1970 AUTHOR: Arua Oko Omaka, BA (University of Nigeria), MA (University of Nigeria) SUPERVISOR: Professor Bonny Ibhawoh NUMBER OF PAGES: xi, 271 ii Ph.D. Thesis – A. Omaka; McMaster University – History ILLUSTRATIONS Figures 1. AJEEBR`s sponsored advertisement ..................................................................122 2. ACKBA`s sponsored advertisement ...................................................................125 3. Malnourished Biafran baby .................................................................................217 Tables 1. WCC`s sickbays and refugee camp medical support returns, November 30, 1969 .....................................................................................................................171 2. Average monthly deliveries to Uli from September 1968 to January 1970.........197 Map 1. Proposed relief delivery routes ............................................................................208 iii Ph.D. Thesis – A. Omaka; McMaster University – History ABSTRACT International humanitarian organizations played a prominent role -

REFORMING URBAN LAWS in AFRICA a PRACTICAL GUIDE Authors: Stephen Berrisford and Patrick Mcauslan

REFORMING URBAN LAWS IN AFRICA A PRACTICAL GUIDE Authors: Stephen Berrisford and Patrick McAuslan Published by the African Centre for Cities (ACC), Cities Alliance, United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) and Urban LandMark. African Centre for Cities, University of Cape Town, Environmental & Geographical Science Building, Upper Campus, Rondebosch, 7701, South Africa Cities Alliance, Rue Royale 94, 3rd Floor, 1000 Brussels, Belgium UN-Habitat, United Nations Avenue, Nairobi, Kenya Urban LandMark, c/o Council for Scientific and Industrial Research – Built Environment, Meiring Naudé Road, Pretoria, 0001, South Africa ISBN 978-0-620-74707-3 © Stephen Berrisford 2017 Production, including editing, design and layout by Clarity Editorial cc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmItted, in any form or by any means without prior permission from the publishers. CONTENTS Foreword and acknowledgements 2 Introduction 3 Purpose of this guide 6 Characteristics of urban Sub-Saharan Africa 8 Urban law in Sub-Saharan Africa 9 A new approach to urban legal reform 10 Triggers for urban legal reform 11 Considerations when initiating reforms 14 The importance of meaningful stakeholder consultation 22 Key stakeholder groups 23 Considerations when consulting stakeholders 26 Practical preparations for drafting new urban laws 32 Establish the terms of reference 33 Identify the problem 36 Outline three legal options 40 Generate a policy paper 45 Characteristics of effective urban legislation 46 Passing the responsibility on to politicians 50 Key steps in the legislative process 50 Implementing new urban laws 52 Monitoring the effects of the new law and making adjustments 53 Indicators to measure impact 53 Monitoring and evaluation roles 54 Templates for reporting 54 Conclusion 55 Notes and references 56 Foreword and acknowledgements he idea for this guide emerged at developed, drafted and processed. -

International Criminal Justice in Africa, 2016

International Criminal Justice in Africa, 2016 HJ van der Merwe Gerhard Kemp (eds) Strathmore University Press is the publisher of Strathmore University, Nairobi. INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL JUSTICE IN AFRICA, 2016 Copyright © Konrad Adenauer Stiftung ISBN 978-9966-021-17-5 Year of publication 2017 Cover design and Layout by John Agutu Email: [email protected] Printed by Colourprint Ltd., P.O. Box 44466 – 00100 GPO Nairobi CONTENTS List of editors and authors ............................................................................... v Abbreviations .................................................................................................. vii List of Cases .................................................................................................... xi List of Legal Instruments ................................................................................ xxi Preface ............................................................................................................. xxxiii Introduction ..................................................................................................... xxxv Annual Report 2016 .............................................................................. xli HJ van der Merwe Introduction ..................................................................................................... xlix Rapport Annuel 2016 ............................................................................ lvi HJ van der Merwe 1. The Present and Future of Universal Jurisdiction in Africa: Lessons -

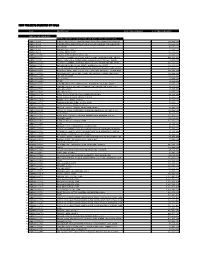

South – East Zone

South – East Zone Abia State Contact Number/Enquires ‐08036725051 S/N City / Town Street Address 1 Aba Abia State Polytechnic, Aba 2 Aba Aba Main Park (Asa Road) 3 Aba Ogbor Hill (Opobo Junction) 4 Aba Iheoji Market (Ohanku, Aba) 5 Aba Osisioma By Express 6 Aba Eziama Aba North (Pz) 7 Aba 222 Clifford Road (Agm Church) 8 Aba Aba Town Hall, L.G Hqr, Aba South 9 Aba A.G.C. 39 Osusu Rd, Aba North 10 Aba A.G.C. 22 Ikonne Street, Aba North 11 Aba A.G.C. 252 Faulks Road, Aba North 12 Aba A.G.C. 84 Ohanku Road, Aba South 13 Aba A.G.C. Ukaegbu Ogbor Hill, Aba North 14 Aba A.G.C. Ozuitem, Aba South 15 Aba A.G.C. 55 Ogbonna Rd, Aba North 16 Aba Sda, 1 School Rd, Aba South 17 Aba Our Lady Of Rose Cath. Ngwa Rd, Aba South 18 Aba Abia State University Teaching Hospital – Hospital Road, Aba 19 Aba Ama Ogbonna/Osusu, Aba 20 Aba Ahia Ohuru, Aba 21 Aba Abayi Ariaria, Aba 22 Aba Seven ‐ Up Ogbor Hill, Aba 23 Aba Asa Nnetu – Spair Parts Market, Aba 24 Aba Zonal Board/Afor Une, Aba 25 Aba Obohia ‐ Our Lady Of Fatima, Aba 26 Aba Mr Bigs – Factory Road, Aba 27 Aba Ph Rd ‐ Udenwanyi, Aba 28 Aba Tony‐ Mas Becoz Fast Food‐ Umuode By Express, Aba 29 Aba Okpu Umuobo – By Aba Owerri Road, Aba 30 Aba Obikabia Junction – Ogbor Hill, Aba 31 Aba Ihemelandu – Evina, Aba 32 Aba East Street By Azikiwe – New Era Hospital, Aba 33 Aba Owerri – Aba Primary School, Aba 34 Aba Nigeria Breweries – Industrial Road, Aba 35 Aba Orie Ohabiam Market, Aba 36 Aba Jubilee By Asa Road, Aba 37 Aba St. -

African Origins of International Law: Myth Or Reality? Jeremy I

Florida A&M University College of Law Scholarly Commons @ FAMU Law Journal Publications Faculty Works 2015 African Origins of International Law: Myth or Reality? Jeremy I. Levitt Florida A&M University College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://commons.law.famu.edu/faculty-research Part of the African History Commons, International Law Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Jeremy I. Levitt, African Origins of International Law: Myth or Reality? 19 UCLA J. Int'l L. Foreign Aff. 113 (2015) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Works at Scholarly Commons @ FAMU Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ FAMU Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE AFRICAN ORIGINS OF INTERNATIONAL LAW: MYTH OR REALITY? Jeremy 1. Levitt.* ABSTRACT This Article reconsiders the prevalent ahistorical assumption that international law began with the Treaty of Westphalia. It gathers together considerable historical evidence to conclude that the ancient world, particularly the New Kingdom period in Egypt or Kemet from 1570-1070 BeE, deployed all three of what today we would call sources of international law. African states predating the modern European nation state by nearly 6000 years engaged in treaty relations (the Treaty of Kadesh), and applied rules ofcustom (the MA 'AT) andgeneral principles of law (as enumerated in the Egyptian Bill ofRights). While Egyptologists and a few international lawyers have acknowledged these facts, scholarly * Jeremy 1. Levitt, J.D., Ph.D., is Vice-Chancellor's Chair and former Dean, University of New Brunswick Law School. -

Law Enforcement in Postcolonial Africa: Interfacing Indigenous and English Policing in Nigeria Nọnso Okafo IPES Working Paper No 7, May 2007

INTERNATIONAL POLICE EXECUTIVE SYMPOSIUM WORKING PAPER NO 7 LAW ENFORCEMENT IN POSTCOLONIAL AFRICA: INTERFACING INDIGENOUS AND ENGLISH POLICING IN NIGERIA Nọnso Okafo M A Y 2 0 0 7 www.IPES.info The IPES Working Paper Series is an open forum for the global community of police experts, researchers, and practitioners provided by the International Police Executive Symposium (IPES). It intends to contribute to worldwide dialogue and information exchange in policing issues by providing an access to publication and the global public sphere to the members of the interested community. In essence, the Working Paper Series is pluralist in outlook. It publishes contributions in all fields of policing and manuscripts are considered irrespective of their theoretical or methodological approach. The Series welcomes in particular contributions from countries of the South and those countries of the universe which have limited access to Western public sphere. Members of the editorial board are Dominique Wisler (editor-in-chief, Khartoum, Sudan), Rick Sarre (professor of Law and Criminal Justice at the University of South Australia, Adelaide), Kam C. Wong (associate professor and chair of the Department of Criminal Justice of Xavier University, Ohio), and Onwudiwe Ihekwoaba (associate professor of Administration of Justice at Texas Southern University). Manuscripts can be sent electronically to the editorial board ([email protected]) or National Focal Points (see www.IPES.info ). © 2007 by Nonso Okafo . All rights reserved. Short sections of this text, not to exceed two paragraphs, might be quoted without explicit permission provided full credit is given to the source. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the International Police Executive Symposium. -

Harnischfeger Igbo Nationalism & Biafra Long Paper

Igbo Nationalism and Biafra Johannes Harnischfeger, Frankfurt Content 0. Foreword .................................................................... 3 1. Introduction 1.1 The War and its Legacy ....................................... 8 1.2 Trapped in Nigeria.............................................. 13 1.2 Nationalism, Religion, and Global Identities....... 17 2. Patterns of Ethnic and Regional Conflicts 2.1 Early Nationalism ............................................... 23 2.2 The Road to Secession ...................................... 31 3. The Defeat of Biafra 3.1 Left Alone ........................................................... 38 3.2 After the War ...................................................... 44 4. Global Identities and Religion 4.1 9/11 in Nigeria .................................................... 52 4.2 Christian Solidarity ............................................. 59 5. Nationalist Organisations 5.1 Igbo Presidency or Secession............................ 64 2 5.2 Internal Divisions ................................................ 70 6. Defining Igboness 6.1 Reaching for the Stars........................................ 74 6.2 Secular and Religious Nationalism..................... 81 7. A Secular, Afrocentric Vision 7.1 A Community of Suffering .................................. 86 7.2 Roots .................................................................. 91 7.3 Modernism.......................................................... 97 8. The Covenant with God 8.1 In Exile............................................................. -

ABIA ORGANIZED CRIME FACTS.Cdr

ORGANIZED CRIME FACTS ABIA STATE Abia State with an estimated population of 2.4 million and records straight. predominantly of Igbo origin, has recently come under the limelight due to heightened insecurity trailing South-Eastern Through its bi-annual publications of organized crime facts states. With the spike in attacks of police officers and police of each of the states in Nigeria, Eons Intelligence attempts stations, correctional facilities and other notable public and to augment the dearth of updated and timely release of private properties and persons in some selected Eastern national crime statistics by objectively providing an States of the Nation, speculations have given rise to an assessment of the situation to provide answers that will underlying tone that denotes all Eastern States as assist all stakeholders to make an informed decision. presenting an uncongenial image of a hazardous zone, Abia State, which shares a boundary with Imo State to the which fast deteriorates into a notorious terrorist region. West, has started gaining the reputation for being one of the The myth of more violent South-Eastern States than their violent Eastern states in the light of recent insecurity Northern counterparts cuts across all social media and happenings in Imo State. Some detractors have gone to the social status amongst the elites, expatriates, the rich, the extent of relying on personal perceptions, presumptions, poor, and the ugly, sending culpable fears amidst all. one-off incidents, conspiracy deductions, the power of invisible forces, or the scramble for resources to form an Hence, it is necessary to use verified statistics that use a opinion. -

Induction Strategy of Igbo Entrepreneurs and Micro-Business Success

ACTA UNIV. SAPIENTIAE, ECONOMICS AND BUSINESS, 4 (2016) 43–65 DOI: 10 .1515/auseb-2016-0003 Induction Strategy of Igbo Entrepreneurs and Micro-Business Success: A Study of Household Equipment Line, Main Market Onitsha, Nigeria Obunike CHINAZOR LADY-FRANCA Federal University Ndufu-Alike, Ikwo, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Department of Business Administration/Entrepreneurial Studies P .M .B . 1010, Abakaliki, Ebonyi State, Nigeria e-mail: ladyfranca8@gmail .com Abstract. This work justifies the “Igba-odibo” (Traditional Business School) concept as a business strategy for achieving success in business which is measured through business/opportunity utilization, customer relationship/ business networking and capital acquisition for business . It gives the in-depth symbolic interpretation and application of the dependent and independent variables used. The paper extends its discussion on the significance of these business strategies as practised among Igbo entrepreneurs and on how they equip Igbo entrepreneurs to immensely contribute their quotas in the area of developing entrepreneurship in Nigeria in particular and the globe in general . Research questions were formulated to investigate the relationship between business strategy and success . Related literature was reviewed . The study population covers the household equipment line of Main Market Onitsha in Anambra State, Nigeria, which has shop capacities of over five hundred, which were used to assume the population of the study – out of the 300 questionnaires administered to the directors of the business or the Masters/Mistresses, who were the business owners during the study, 180 were returned, 73 were invalid, so the researcher was left with 107 valid questionnaires to work with . The data collected were tested using frequency tables, percentages, Pearson Product-Moment correlation analysis, and regression analysis . -

Law and Stagnation in Africa by Robert Seidman

CHAPTER 12 LAW AND STAGNATION IN AFRICA Robert Seidman The dual economies of Africa during the colonial era funnelled its riches into the coffers of the metropolitan countries. They still do. The "Development Decade" of the sixties ended as it began. Practically all Africans remain desperately poor. Societies are as they are because of the ways in which the people within them engage in repetitive patterns of behaviour. These repetitive patterns of behaviour constitute the institutions of the society. What makes Africa poor is that the established patterns of behaviour do not result in a high level of productivity in the countryside, and permit the surpluses generated in the export enclave to be siphoned off to the rich nations of the world. Repetitive patterns of behaviour are defined by rules or norms. They state the way in which we expect people in particular roles to behave. I act as a father, a professor, or a citizen because there are rules, supported by sanctions of various sorts, that induce me to act more or less in the prescribed way. Because the state has under its control the largest body of organized agents (the bureaucracy in all its ramifications) and the largest body of armed men (the police, the anny, goalers and bailiffs and sheriffs) and because through constitutions and legislatures and courts it has acquired a legitimate sovereignty, better than any other body, it can consciously change the institutions of the society. Laws are norms. They state how people are supposed to behave on pain of sanction. By changing the laws, the government can change the institutions of the society. -

New Projects Inserted by Nass

NEW PROJECTS INSERTED BY NASS CODE MDA/PROJECT 2018 Proposed Budget 2018 Approved Budget FEDERAL MINISTRY OF AGRICULTURE AND RURAL SUPPLYFEDERAL AND MINISTRY INSTALLATION OF AGRICULTURE OF LIGHT AND UP COMMUNITYRURAL DEVELOPMENT (ALL-IN- ONE) HQTRS SOLAR 1 ERGP4145301 STREET LIGHTS WITH LITHIUM BATTERY 3000/5000 LUMENS WITH PIR FOR 0 100,000,000 2 ERGP4145302 PROVISIONCONSTRUCTION OF SOLAR AND INSTALLATION POWERED BOREHOLES OF SOLAR IN BORHEOLEOYO EAST HOSPITALFOR KOGI STATEROAD, 0 100,000,000 3 ERGP4145303 OYOCONSTRUCTION STATE OF 1.3KM ROAD, TOYIN SURVEYO B/SHOP, GBONGUDU, AKOBO 0 50,000,000 4 ERGP4145304 IBADAN,CONSTRUCTION OYO STATE OF BAGUDU WAZIRI ROAD (1.5KM) AND EFU MADAMI ROAD 0 50,000,000 5 ERGP4145305 CONSTRUCTION(1.7KM), NIGER STATEAND PROVISION OF BOREHOLES IN IDEATO NORTH/SOUTH 0 100,000,000 6 ERGP445000690 SUPPLYFEDERAL AND CONSTITUENCY, INSTALLATION IMO OF STATE SOLAR STREET LIGHTS IN NNEWI SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 7 ERGP445000691 TOPROVISION THE FOLLOWING OF SOLAR LOCATIONS: STREET LIGHTS ODIKPI IN GARKUWARI,(100M), AMAKOM SABON (100M), GARIN OKOFIAKANURI 0 400,000,000 8 ERGP21500101 SUPPLYNGURU, YOBEAND INSTALLATION STATE (UNDER OF RURAL SOLAR ACCESS STREET MOBILITY LIGHTS INPROJECT NNEWI (RAMP)SOUTH LGA 0 30,000,000 9 ERGP445000692 TOSUPPLY THE FOLLOWINGAND INSTALLATION LOCATIONS: OF SOLAR AKABO STREET (100M), LIGHTS UHUEBE IN AKOWAVILLAGE, (100M) UTUH 0 500,000,000 10 ERGP445000693 ANDEROSION ARONDIZUOGU CONTROL IN(100M), AMOSO IDEATO - NCHARA NORTH ROAD, LGA, ETITI IMO EDDA, STATE AKIPO SOUTH LGA 0 200,000,000 11 ERGP445000694 -

Conflicts Between African Traditional Religion and Christianity in Eastern Nigeria: the Igbo Example

SGOXXX10.1177/2158244017709322SAGE OpenOkeke et al. 709322research-article2017 Article SAGE Open April-June 2017: 1 –10 Conflicts Between African Traditional © The Author(s) 2017 https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017709322DOI: 10.1177/2158244017709322 Religion and Christianity in Eastern journals.sagepub.com/home/sgo Nigeria: The Igbo Example Chukwuma O. Okeke1, Christopher N. Ibenwa1, and Gloria Tochukwu Okeke1 Abstract Conflict is a universal phenomenon that is inevitable in human interaction. Hence, it cannot be avoided in the interaction between Christianity and African Traditional Religion. Since Christianity came in contact with the traditional religion, there has always been a sharp conflict between traditionalists and Christians. This bitter conflict has led to wanton destruction of lives and property, and this has become a source of great worry to the writers. This work investigates the conflicts existing between the two religions since the introduction of Christianity in Igbo land. It examines the nature, pattern, rationale for the conflicts. The method adopted by this study is qualitative and comparative. Both oral interviews and library materials were used. The study validates the following: There is occasional destruction of lives and property and demolition of the people’s artifacts and groves by Christians, and this has led to reduction in the sources of income of the people, and in the tourist sites available in most Igbo towns. It also led to syncretism in the people’s culture. Finally, it helped in refining some obnoxious beliefs and practices of the Igbo race. Keywords Igbo, conflict, criminology, social sciences, ATR, Christianity, culture Introduction the first human inhabitants of Igbo land must have come from areas further north, possibly from the Niger confluence.