An Ethnography on the Maizbhandar: Locating Within Cultural, Religious and Political Dimensions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BANGLADESH Annual Human Rights Report 2016

BANGLADESH Annual Human Rights Report 2016 1 Cover designed by Odhikar with photos collected from various sources: Left side (from top to bottom): 1. The families of the disappeared at a human chain in front of the National Press Club on the occasion of the International Week of the Disappeared. Photo: Odhikar, 24 May 2016 2. Photo: The daily Jugantor, 1 April 2016, http://ejugantor.com/2016/04/01/index.php (page 18) 3. Protest rally organised at Dhaka University campus protesting the Indian High Commissioner’s visit to the University campus. Photo collected from a facebook page, https://www.facebook.com/SaveSundarbans.SaveBangladesh/videos/713990385405924/ 4. Police on 28 July fired teargas on protesters, who were heading towards the Prime Minister's Office, demanding cancellation of a proposed power plant project near the Sundarbans. Photo: The Daily Star, 29 July 2016, http://www.thedailystar.net/city/cops-attack-rampal-march-1261123 Right side (from top to bottom): 1. Activists of the Democratic Left Front try to break through a police barrier near the National Press Club while protesting the price hike of natural gas. http://epaper.thedailystar.net/index.php?opt=view&page=3&date=2016-12-30 2. Ballot boxes and torn up ballots at Narayanpasha Primary School polling station in Kanakdia of Patuakhali. Photo: Star/Banglar Chokh. http://www.thedailystar.net/frontpage/5-killed-violence-1198312 3. On 28 July the National Committee to Protect, Oil, Gas, Natural Resources, Power and Ports marched in a protest rally towards the Prime Minister’s office. Photo: collected from facebook. -

The Accounting Information System Performs A

ABC Journal of Advanced Research, Volume 7, No 2 (2018) ISSN 2304-2621(p); 2312-203X (e) Origins, Evolution and Current Activities of Sunni Salafi Jihadist Groups in Bangladesh Labiba Rahman Schar School of Policy and Government, George Mason University, VA 22030, USA Corresponding Contact: Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Despite its global recognition as a moderate Muslim country, Bangladesh has been experiencing increasing bouts of religious fundamentalism and militant activities since 2005. This phenomenon is not altogether novel to the country. During the Liberation War of 1971, Bengali freedom fighters faced staunch opposition from the Pakistani armed forces as well as Islamist militias under the control of Jamaat-e-Islami, an Islamist political party. Even after attaining its independence, Bangladesh has struggled to uphold the pillars of democracy and secularism due to political, social and religious drivers. Between January 2005 and June 2015, nearly 600 people have died in Islamic terrorist attacks in the country. These militant outfits either have close ties to or are part of Al Qaeda Indian Subcontinent (AQIS) and the Islamic State (ISIS). Despite such troubling signs and the fact that it is the fourth largest Muslim majority country in the world, Bangladesh has generally received little attention from academics of security studies. This paper aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of the drivers and trends of Sunni Salafi jihadist groups operating in Bangladesh to ascertain the implications for counterterrorism activities. Political, social and religious interventions that go beyond the hard approach must be undertaken to control the mounting threat of Islamist terrorism to the security and stability of the nation. -

Cgs Peace Report

CGS PEACE REPORT an initiative of BPO Volume 1, Issue 4 November-December 2017 Photo courtesy: The Daily Star Crime and Violence in A Global Overview on Bangladesh: Violence Against An analysis from BPO Women Bangladesh’s Drive to Understanding Violent Eliminate Violence Against Extremism through Women Micronarratives: The Case of Kishoreganj CGS PEACE REPORT an initiative of BPO- Bangladesh Peace Observatory Volume 1, Issue 4 November- December 2017 BPO Advisory Board Stop Violence Coalition Bangladesh Police National Defence College ActionAid The Society for Environmental and Human Development The Daily Star Centre for Genocide Studies Editorial Board Professor Imtiaz Ahmed Professor Amena Mohsin Professor Delwar Hossain Mr. Hossain Ahmed Taufiq Ms. Farhana Razzak Mr. Humaun Kabir Mr. Amranul Hoque Maruf Mr. Mahfuzur Rahman Ms. Sabiha Sultana Mr. Ashique Mahmud Ms. Faizah Sultana Ms. Sharin Fatema Disclaimer Unless otherwise stated, authors are responsible for the views expressed in their respective papers. Table of Contents From the Editor’s Desk ...................................................................................................................... 1 Crime and Violence in Bangladesh: An analysis from BPO........................................................ 3 Part A: Violence Update (October- November 2017) .......................................................... 3 Part B: Trends of Violence against Women ........................................................................... 10 Violence against Women: The Conceptual -

Innovative Research

International Journal of Innovative Research International Journal of Innovative Research, 3(3):100–111, 2018 ISSN 2520-5919 (online) www.irsbd.org REVIEW PAPER Impact of Muslim Militancy and Terrorism on Bangladesh Politics Abul Basher Khan* Department of Economics and Sociology, Patuakhali Science and Technology University, Dumki, Patuakhali-8602, Bangladesh. ARTICLE HISTORY ABSTRACT Received: October 10, 2018 The Muslim militant groups have made some grounds for implementing their Revised : November 8, 2018 activities uninterruptedly in world politics. But as a major Muslim country in Accepted: November 21, 2018 Bangladesh the history of the Islamic militancy, from both outer and inner source, is Published: December 31, 2018 of about 30 years. In a recent research analysis, it is seen that there are about 135 Islamic religious groups found in Bangladesh those who have a direct or indirect *Corresponding author: connection with the militant devastation is investigated within the activities of other [email protected] political parties. In this perspective of Bangladesh politics, to find out the proper information about these Islamic groups’ secondary data sources has been used along with analyzing various concepts. In the political arena of Bangladesh, the “alliance politics” is introduced only to achieve and sustain the empowerment to rule the country as well as for their interest during the election. According to the practical analysis, these Islamic groups were included with the major political parties only to use them during the election. By this time, much more public and secret Islamic militant organizations have chosen the way of militancy for the sake of building up Bangladesh as an Islamic Shariah-based country. -

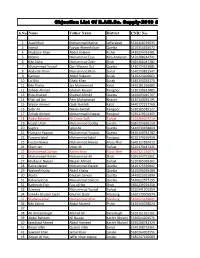

Objection List of B.A / B.Sc. Supply-2019 & Annual-2020

Objection List Of B.A/B.Sc. Supply-2019 & Annual-2020 S.No Name Father Name District CNIC No. 2 Asad Khan Mohammad Bachal Jaffarabad 5320410729635 3 Komal Fayyaz Ahmed Khan Quetta 3210354355672 4 Mudassir Khan Abdul Haleem Pishin 5430294761481 5 Momin Muhammad Essa Killa Abdullah 5420288244741 6 Bibi Aisha Muhammad Zakir Zhob 5650366047282 7 Muhammad Yousaf Qari Wajeed Gul Quetta 1430124553081 8 Abdullah Khan Muhammad Khan Ziarat 5540293812547 9 Kamran Abdul Hakeem Surab 5120223206063 10 Lal Bibi Ghabi Khan Surab 5180103335270 11 Bibi Thaira Jan Muhammad Kalat 5440181266080 12 Zaheer Ahmed Ghulam Rasool Panjgoor 5230130612885 13 Rida Shakeel Shakeel Ahmed Quetta 5440003015707 14 Ellah ud Din Peer Muhammad Kharan 5130149064195 15 Waqar Ahmed Qadir Bakhsh Kalat 5440177227769 16 Sabir Ali Maula Bakhsh Panjgoor 5230165585127 17 Zohaib Ahmed Mohammad Ishaque Panjgoor 5230179674353 18 Abdul Rehman M. Umer Salfi Turbat 5220369074219 19 Inayat Ullah Muhammad Saddiq Loralai 5630294636159 20 Sughra Iqbal Ali Quetta 5440033458804 21 Humaira Yaqoob Muhammad Yaqoob Quetta 5440149781782 22 Farzana Iqbal Muhammad Iqbal Panjgoor 4220170265958 23 Fouzia Nawaz Muhammad Nawaz Musa Khel 5640117830413 24 Sham Jan Umid Ali Turbat 5220179447425 25 Muhammad Zaman Rahim Khan Musa Khel 5640121160975 26 Muhammad Rahim Muhammad Ali Zhob 5650343752961 27 Mudassir Naseer Naseer Ahmed Turbat 5220365069301 28 Rabia Nazeer Muhammad Nazeer Quetta 5440175336842 29 Waleed Khaliq Abdul Khaliq Quetta 5440096039489 30 Abida Ghulam Sarwar Quetta 5440025515899 31 Rabia Saleem -

Piety and Brotherhood Mark Eid Celebrations

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 Lekhwiya stun Al Rayyan to INDEX DOW JONES QE NYMEX QATAR 2, 3, 16 COMMENT 14, 15 Non-hydrocarbons GDP REGION 3 BUSINESS 1 – 8 win Sheikh share of 65% to cushion 18,326.51 11,297.50 46.09 ARAB WORLD 3 CLASSIFIED 6 +241.06 -22.89 +0.21 INTERNATIONAL 4 – 13 SPORTS 1 – 8 oil fall impact on Qatar Jassim Cup +1.33% -0.20% +0.46% Latest Figures published in QATAR since 1978 TUESDAY Vol. XXXVII No. 10210 September 13, 2016 Dhul-Hijja 11, 1437 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Emir, Father Emir receive well-wishers Piety and In brief brotherhood QATAR | Health HGH receives 500 mark Eid emergency cases Hamad General Hospital (HGH) received more than 500 emergency cases yesterday from 6am to 5pm. Five accidents were reported, celebrations including one that caused the death of a person. Al Wakra Hospital Special Eid al-Adha programmes emergency received more than got under way yesterday, with Greetings exchanged 200 cases during the same period Qatar Tourism Authority and its HH the Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad yesterday. Ambulance Service partners lining up a series of shows al-Thani, in telephone calls yesterday, took more than 200 calls seeking and activities exchanged congratulations on the help. Most cases were minor and occasion of Eid al-Adha with a number were discharged from the hospital By Ayman Adly of Arab and Islamic countries’ leaders. yesterday itself. The Paediatric Staff Reporter HH the Emir exchanged congratulations Emergency Centre (PEC) at Al Sadd with Saudi Crown Prince, Deputy Prime received a total of 266 cases from HH the Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani and HH the Father Emir Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa al-Thani received a number Minister and Minister of Interior Prince 6am to 5pm, followed by 107 at PEC of well-wishers on the occasion of Eid al-Adha at Al Wajbah Palace yesterday morning. -

BPS-14) Supreme Court of Pakistan, Punjab/Islamabad Skill Test Result Sr

Overall Applicant Stenotypist (BPS-14) Supreme Court Of Pakistan, Punjab/Islamabad Skill Test Result Sr. No Reg No. Type Typing WPM Shorthand WPM Name Father Name CNIC 1 1085261 1142 78 80 Arslan Farooq Muhammad Farooq 37405-5762183-9 2 712922 1142 61 80 MUHAMMAD RIZWAN RAFIQ MUHAMMAD RAFIQ 61101-5588265-3 3 1085874 1142 59 80 SALMAN ASLAM MUHAMMAD ASLAM 37405-3060477-5 4 712473 1142 55 80 MUHAMMAD HASHIM CHOHAN ABDUL RAHMAN 61101-6581746-5 5 1082647 1142 54 80 ADEEL-UR-REHMAN ABID REHMAN 41304-2428236-1 6 1082677 1142 53 80 Waqas Ahmed Muhammad Sadiq 37101-2564725-3 7 1086411 1142 52 80 USAMA BIN TARIQ SHEIKH M TARIQ 35202-5215852-7 8 1116413 1142 52 80 TOUSEEF AHMAD MUHAMMAD SARWAR 35101-9065715-1 9 1079464 1142 52 80 NADIR ALI WAZIR ALI 35201-5544408-9 10 1080349 1142 52 80 MUHAMMAD UMAIR ZAHID ZAHID HAMEED 37405-3766935-9 11 1088334 1142 51 80 AZAM SHAREEF MUHAMMAD SHAREEF 35101-1678158-3 12 1082263 1142 51 80 NABEEL AHMAD NAZIR AHMAD 35201-5664985-3 13 1086722 1142 51 80 muhammad usman muhammad ashraf 35101-4396203-9 14 1089581 1142 51 80 AMIR KHAN GHULAM ULLAH KHAN 61101-5204092-9 15 1088101 1142 50 80 MUHAMMAD ASIF ABBAS ALI 34501-1566888-7 16 1079407 1142 50 80 MUHAMMAD JUNAID FAYYAZ AHMAD 35102-6936764-9 17 712830 1142 50 80 Muhammad Arsalan Yaqoob Muhammad Yaqoob 61101-9567628-1 18 1113819 1142 50 80 Syed Rashid Maqsood M Ali Shah 36502-0832573-9 19 1084766 1142 50 80 atta-ul-mustafa arshad MUHAMMAD ARSHAD 35101-9921458-5 20 1087506 1142 50 80 muhammad aleem muhammad rafiq javeed 35102-1902267-3 21 1086353 1142 49 80 KAMRAN -

Local Drivers and Dynamics of Youth Radicalisation in Bangladesh

Local Drivers and Dynamics of Youth Radicalisation in Bangladesh June, 2017 Bangladesh Institute of Peace and Security Studies (BIPSS) Bangladesh Institute of Peace and Security Studies (BIPSS) House No.: 425, Road No.: 07, DOHS, Baridhara Dhaka-1212, Bangladesh Telephone: 8419516-17 Fax: 880-2-8411309 E-mail: [email protected] URL: www.bipss.org.bd First Publication : October 2017 Copyright Bangladesh Institute of Peace and Security Studies (BIPSS) No part of this publication may be reproduced or stored, in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, or otherwise, without permission of the Editor of the Journal. Cover Design & Illustration : Md. Nazmul Alam ISBN 978-984-34-3227-8 Price : 500 (BTD) 10 (US$) Published by Bangladesh Institute of Peace and Security Studies (BIPSS) House No.: 425, Road No.: 07, DOHS, Baridhara, Dhaka-1212, Bangladesh Printed at S.A Printers Ltd., 1/1 Sheikh Shaheb Bazar, Azimpur, Dhaka, Bangladesh Preface The rise of religious radicalisation leading to terrorism has risen in Bangladesh in recent times. The country was founded on the basis of religious harmony and diverseness of ethnicity and culture, a unique characteristic among Muslim majority countries. In recent years, Bangladesh has suffered from transnational extremism, which has crept into the very fabric of the society. In recent years’ violent extremism is a result of Islamist radicalisation considered as one of the major concerns in Bangladesh. After the Holey Artisan Bakery attack in July 2016, the depth of violent extremism in Bangladesh unearthed the depth of extremists’ influence in our society. -

A Sufi Movement in Modern Bangladesh

d A SUFI MOVEMENT IN MODERN BANGLADESH Peter J. Bertocci 1 Prologue Comilla 1967. Abdur Rahman, the rickshaw puller, sits in the middle of the circle. A gaunt, graying man, with intense, flashing eyes, he cradles a dotara, the mandolin-like instrument that often accompanies performances of indigenous Bengali music. Next to him, a world-worn pushcart driver plucks his ektara, so-called for the single string from which it emits pulsing monotones in backing up a song. Others in the group, also nondescript urban laborers of rural vintage, provide percussion with little more than blocks of wood which, when struck, produce sharp resonating, rhythmic clicks, or with palm-sized brass cymbals that, clashed together by cupped hands, sound muted, muffled clinks. This rhythmic ensemble, miraculously, does not drown out Abdur Rahman’s melodic lyrics, however, as he belts out, in solo fashion, yet another in his seemingly inexhaustible repertoire of tunes, loud, clear, never missing a beat or note. “Ami nouka, tumi majhi . ,” goes the refrain, “I am the boat, you the boatman . ,” implying “take me where you will.” As his voice rises in intensity, moving from moderate to rapid tempo, others in the 52 stuffy little room respond to the music with the chanting of the name of Allah, all in mesmerizing unison: “Allah-hu, Allah-hu, Allah-hu . ” At the height of the music’s intensity, some rise to to sway and rock in an attempt to dance. A few teeter to a near-fall, to be caught by their fellows, themselves only slightly less enraptured, before hitting the floor. -

THRESHOLD RELIGION Th Reshold Religion Ed

THRESHOLD RELIGION THRESHOLD Th reshold Religion ed. by Tiziano Tosolini Th reshold Religion Aaa bbb ccc ddd eee ff f ggg hhh jjj iii lll mmm nnn ooo ppp qqq rrr sss ttt uuu vvv www yyy zzz aaa bbb ccc ddd eee ff f ggg hhh Tosolini Tiziano jjj iii lll mmm nnn ooo ppp qqq rrr sss ttt uuu vvv www yyy zzz aaa bbb ccc ddd eee ff f ggg hhh jjj iii lll mmm nnn ooo ppp qqq rrr sss ttt uuu vvv www yyy zzz aaa bbb ccc ddd eee ff f ggg hhh jjj iii lll mmm nnn ooo ppp qqq rrr sss ttt uuu vvv www yyy zzz aaa bbb ccc ddd eee ff f ggg hhh jjj iii lll mmm nnn ooo ppp qqq rrr sss ttt uuu vvv www yyy zzz aaa bbb ccc ddd eee ff f ggg hhh jjj iii lll mmm nnn ooo ppp qqq rrr sss ttt uuu vvv www yyy zzz aaa bbb ccc ddd eee ff f ggg hhh jjj iii lll mmm nnn ooo ppp qqq rrr sss ttt uuu vvv www yyy zzz aaa bbb ccc ddd eee ff f ggg hhh jjj iii lll mmm nnn ooo ppp qqq rrr sss ttt uuu vvv www yyy zzz aaa bbb ccc ddd eee ff f ggg hhh jjj iii lll mmm nnn ooo ppp qqq rrr sss ttt uuu vvv www yyy zzz aaa bbb ccc ddd eee ff f ggg hhh jjj iii lll mmm nnn ooo ppp qqq rrr sss ttt uuu vvv www yyy zzz aaa bbb ccc ddd eee ff f ggg hhh jjj iii lll mmm nnn ooo ppp qqq rrr sss ttt uuu vvv www yyy zzz Asian Study Centre Study Asian tudy S C n en ia t s r e A Xaverian Missionaries – Japan threshold religion Asian Study Centre Series FABRIZIO TOSOLINI. -

Atatürk İlkeleri Ve İnkılap Tarihi

TC YILDIZ TEKNİK ÜNİVERSİTESİ 2021 / 2022 Güz Yarıyılı Lisansüstü Başvuruları Değerlendirme Listesi Atatürk İlkeleri ve İnkılap Tarihi Atatürk İlkeleri ve İnkılap Tarihi Doktora (Alan İçi) S.No Ad Soyad Durum 1 YAĞMUR YURTSEVER Asil 2 NUR CERAN Kazanamadı 3 ŞEYDA OKUR Kazanamadı 1/469 TC YILDIZ TEKNİK ÜNİVERSİTESİ 2021 / 2022 Güz Yarıyılı Lisansüstü Başvuruları Değerlendirme Listesi Atatürk İlkeleri ve İnkılap Tarihi 2/469 TC YILDIZ TEKNİK ÜNİVERSİTESİ 2021 / 2022 Güz Yarıyılı Lisansüstü Başvuruları Değerlendirme Listesi Atatürk İlkeleri ve İnkılap Tarihi Atatürk İlkeleri ve İnkılap Tarihi Tezli Yüksek Lisans (Alan Dışı) S.No Ad Soyad Durum 1 BÜŞRA AYDIN Asil 2 YASEMİN ŞENYER Asil 3 KADİR CAN BAŞNUH Yedek 4 OĞULCAN KESKİN Yedek 5 TANER UÇAR Yedek 6 HAKAN BAHÇIVANCILAR Yedek 7 BİRCAN GÜRKAL Yedek 8 NUR DAMLA FET Yedek 9 EMRAH COŞKUN Yedek 10 MEHMET TÜRKAN Yedek 11 NAZAN TANRIVER Yedek 12 OĞUZCAN DEMİRÖREN Yedek 13 KENAN SARI Yedek 14 MELİKE DOĞAN Yedek 15 TEKIN TOKDEMİR Yedek 16 YASİN ÜNLÜ Yedek 17 MUHARREM ERENLER Yedek 18 ÖMER KARA Yedek 19 METİN GÜNGÖR Yedek 20 MURATHAN MEMİK KABAK Yedek 21 ZEKERİYA LEVENT EREN Yedek 22 SEVİL ATAKAN Yedek 23 BAŞAK KARAGÖL Yedek 24 UMUT ARAS Yedek 25 ENES SEBAHATTİN KONUK Yedek 26 ÇİĞDEM KALINKAYA Yedek 27 ECEHAN ÖZCAN Yedek 28 OĞUZHAN YEŞİLYURT Yedek 29 ENEZ YILDIRIM GÜR Yedek 30 SEVGİ AKBAL Yedek 3/469 TC YILDIZ TEKNİK ÜNİVERSİTESİ 2021 / 2022 Güz Yarıyılı Lisansüstü Başvuruları Değerlendirme Listesi Atatürk İlkeleri ve İnkılap Tarihi Atatürk İlkeleri ve İnkılap Tarihi Tezli Yüksek Lisans (Alan İçi) -

Bio's Spiritual Leaders and Keynote Speakers

Bio’s Spiritual leaders and Keynote speakers PILGRIMAGE FOR LOVE COMPASSION AND HUMAN UNITY NEW DELHI -AJMER Chairman Universal Sufi Council ~ The Netherlands Murshid Dr. H.J. Karimbakhsh Witteveen, who is calling this Sufi conference together with Peer Mudassir from Pakistan, is one of the former leaders of the International Sufi Movement in Geneva and The Hague. At the same time, he is an economist, who has been a professor in economics, Minister of Finance and vice Prime Minister in the Netherlands and later Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund. He has shown in this career how the inner and outer life can grow together, inspiring and testing each other. As leader of the International Sufi Movement – together with Murshid Hidayat Inayat Khan, the son of Hazrat Inayat Khan – he has succeeded in creating a harmonious cooperation between the different Sufi organizations that are following Hazrat Inayat Khan’s message, creating in that way the Federation of the Sufi Message. Murshid Karimbakhsh now hopes to bring many different leaders of Sufi orders who recognise this universal character of Sufism and a few leaders of mystical orders in other religions harmoniously together in a Sufi conference. Pir Shabda Kahn USA Shabda Kahn serves as Pir (spiritual director) of the Sufi Ruhaniat International, a branch within the spiritual lineage of Pir-o-Murshid Hazrat Inayat Khan. He is also a teacher and performer of Hindustani classical vocal music, Raga, in the Kirana Gharana style, serving as director of the Chisti Sabri School of Music, within the lineage of his teacher Pandit Pran Nath, at whose direction this school was formed and placed in Shabda Kahn's care.