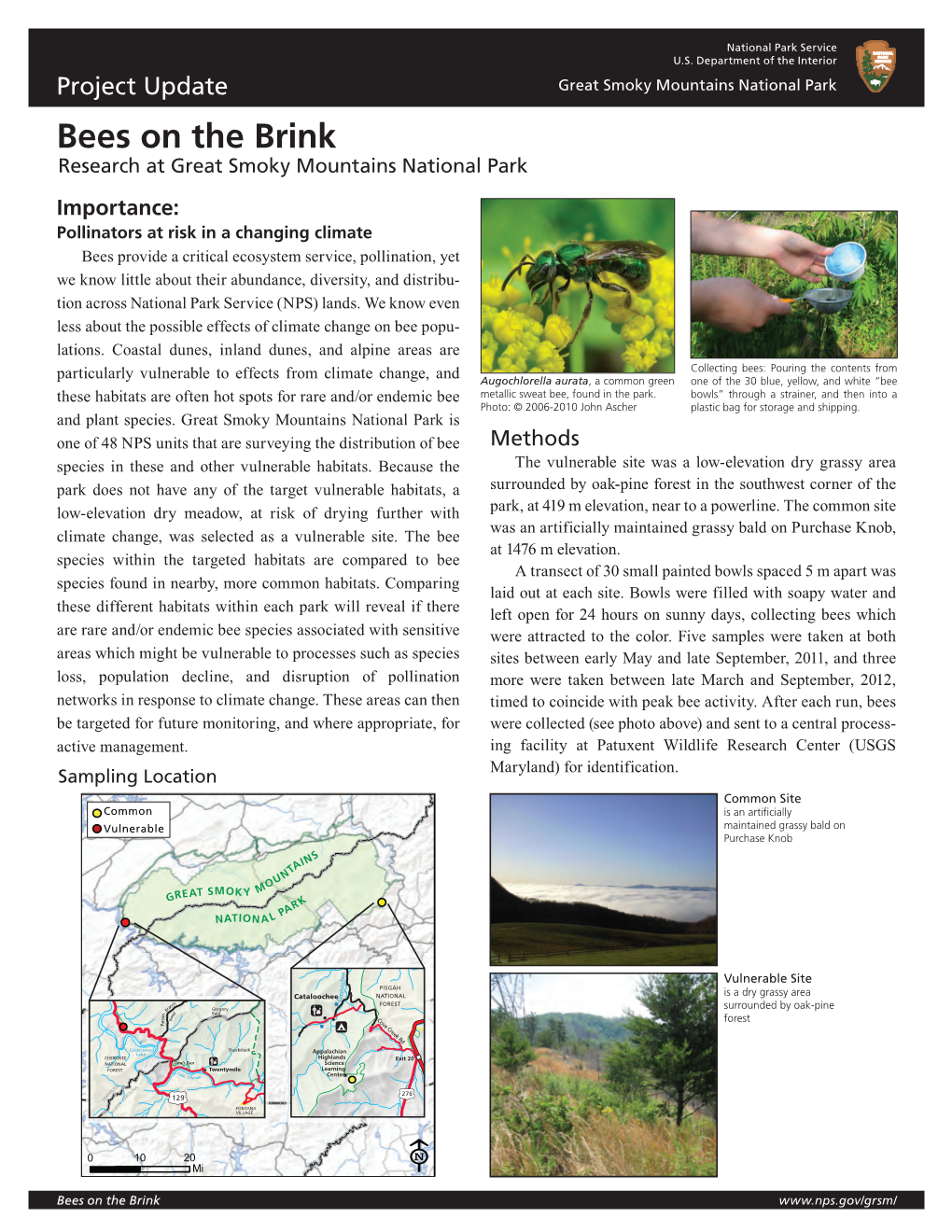

Bees on the Brink

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Conservation and Ecology of Native Bees and Other Pollinators

The conservation and ecology of native bees and other pollinators Colleen Smith [email protected] Rutgers University New Brunswick, New Jersey Outline • Overview of pollination and bee biodiversity • My research on forest bees at Rutgers University • What you can do to support native bees • Bee ID! Outline • Overview of pollination and bee biodiversity • My research on forest bees at Rutgers University • What you can do to support native bees • Bee ID! Pollination: Transfer of pollen grains from anther to stigma ~ 87% of all flowering plants Ollerton et al. 2011 Oikos >2/3 crop species use animal- mediated pollination Klein et al. 2006 J. Applied Ecology Bees Native bees are important pollinators for many crops globally Garibaldi et al 2013 Science 3 bee life history strategies Solitary Social Parasitic • 77% of bee species • 10% of bee • 13% of bee species species 3 bee life history strategies Solitary Social Parasitic • 77% of bee species • 10% of bee • 13% of bee species species Bee life histories: solitary The vast majority of bees! Andrena erigeniae Colletes inaequalis Augochlora pura Pupa Adult bee Egg winter spring fall summer Pre-pupa Pupa Adult bee Egg winter spring fall summer Pre-pupa Pupa Adult bee Only 2 to 3 weeks of a solitary bees’ life! Egg winter spring fall summer Pre-pupa Pupa Adult bee Egg winter spring fall summer Pre-pupa How a solitary bee spends most of its life 3 bee life history strategies Solitary Social Parasitic • 77% of bee species • 10% of bee • 13% of bee species species Cuckoo bees Nomada bee 3 bee life history strategies Solitary Social Parasitic • 77% of bee species • 10% of bee • 13% of bee species species Bombus, Lasioglossum, Halictus Bombus impatiens Lasioglossum spp. -

Sensory and Cognitive Adaptations to Social Living in Insect Societies Tom Wenseleersa,1 and Jelle S

COMMENTARY COMMENTARY Sensory and cognitive adaptations to social living in insect societies Tom Wenseleersa,1 and Jelle S. van Zwedena A key question in evolutionary biology is to explain the solitarily or form small annual colonies, depending upon causes and consequences of the so-called “major their environment (9). And one species, Lasioglossum transitions in evolution,” which resulted in the pro- marginatum, is even known to form large perennial euso- gressive evolution of cells, organisms, and animal so- cial colonies of over 400 workers (9). By comparing data cieties (1–3). Several studies, for example, have now from over 30 Halictine bees with contrasting levels of aimed to determine which suite of adaptive changes sociality, Wittwer et al. (7) now show that, as expected, occurred following the evolution of sociality in insects social sweat bee species invest more in sensorial machin- (4). In this context, a long-standing hypothesis is that ery linked to chemical communication, as measured by the evolution of the spectacular sociality seen in in- the density of their antennal sensillae, compared with sects, such as ants, bees, or wasps, should have gone species that secondarily reverted back to a solitary life- hand in hand with the evolution of more complex style. In fact, the same pattern even held for the socially chemical communication systems, to allow them to polymorphic species L. albipes if different populations coordinate their complex social behavior (5). Indeed, with contrasting levels of sociality were compared (Fig. whereas solitary insects are known to use pheromone 1, Inset). This finding suggests that the increased reliance signals mainly in the context of mate attraction and on chemical communication that comes with a social species-recognition, social insects use chemical sig- lifestyle indeed selects for fast, matching adaptations in nals in a wide variety of contexts: to communicate their sensory systems. -

Native Bee Benefits

Bryn Mawr College and Rutgers University May 2009 Native Bee Benefits How to increase native bee pollination on your farm in several simple steps For Pennsylvania and New Jersey Farmers In this pamphlet, Why are native bees important? Insect pollination services are a highly important you can find out… agricultural input. Two-thirds of crop varieties require animal pollination for production and many crops have higher quality after The most effective native bees insect pollination.1,2,3 Bees are the most important pollinators in in PA and NJ and how to most ecosystems. They facilitate reproduction and improve seed set for half of Pennsylvania’s and New Jersey’s top fruit and identify them 4,5,6 vegetable commodities. Estimated value of their pollination services range from $6 - 263 million each year.7 Their habitat and foraging Honeybee numbers in Pennsylvania and New Jersey have needs been declining over the past several years. Beekeepers recorded overwinter losses of 26- 48% and 17-40% respectively in PA and Strategies for encouraging NJ between 2006 and 2009.8,9,10 These losses are much higher than their presence on your farm the typical 15% losses seen in previous years.10 Although many farmers rent managed honeybees to increase crop yield and quality, Sources of funding surveys of small to medium size PA and NJ farms have shown that native bees provide a substantial portion of pollination services.11,12 By increasing the number and diversity of native bees, PA and NJ farmers may be able to counter rising costs of rented bee colonies while supporting sustainable native plant and pollinator communities. -

Lundiana 8-1 2007.P65

Lundiana 8(1):53-55, 2007 © 2007 Instituto de Ciências Biológicas - UFMG ISSN 1676-6180 SHORT COMMUNICATION Nests of Phacellodomus rufifrons (Wied, 1821) (Aves: Furnariidae) as sleeping shelter for a solitary bee species (Apidae: Centridini) in southeastern Brazil Alexsander A. Azevedo1,2 & Luiz Roberto R. Faria Jr.1,3 1 Laboratório de Sistemática e Ecologia de Abelhas, Departamento de Zoologia & Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia, Conservação e Manejo da Vida Silvestre, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais. Cx. P. 486 - 30.123-970 - Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil. 2 Instituto Biotrópicos de Pesquisa em Vida Silvestre. E-mail: [email protected] 3 Current Address: Programa de Pós-Graduação em Entomologia, Universidade Federal do Paraná. Caixa Postal 19.020, 81.531-980, Curitiba, PR, Brazil. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Sleeping shelters for male Centris (Trachina) fuscata Lepeletier, 1841 (Hymenoptera, Apidae, Centridini) were found in nests of the ovenbird Phacellodomus rufifrons (Wied, 1821) (Furnariidae) in an area of Cerra- do (Brazilian savanna), in the state of Minas Gerais, southeastern Brazil, in September 2003. Each day, male bees departed from the shelter early in the morning, returning to them late in the afternoon. Interactions among males were aggressive when two or more males returned simultaneously to the shelter, and lasted until all of them had either occupied a shelter inside the nest stick-matrix or left the nest proximity. Nests occupied by bird families apparently were preferred by bees, as well as those located nearest to a massive food source, a flowering tree Bowdichia virgilioides Kunth, 1823 (Fabaceae). -

(Native) Bee Basics

A USDA Forest Service and Pollinator Partnership Publication Bee Basics An Introduction to Our Native Bees By Beatriz Moisset, Ph.D. and Stephen Buchmann, Ph.D. Cover Art: Upper panel: The southeastern blueberry bee Habropoda( laboriosa) visiting blossoms of Rabbiteye blueberry (Vaccinium virgatum). Lower panel: Female andrenid bees (Andrena cornelli) foraging for nectar on Azalea (Rhododendron canescens). A USDA Forest Service and Pollinator Partnership Publication Bee Basics: An Introduction to Our Native Bees By Beatriz Moisset, Ph.D. and Stephen Buchmann, Ph.D. Illustrations by Steve Buchanan A USDA Forest Service and Pollinator Partnership Publication United States Department of Agriculture Acknowledgments Edited by Larry Stritch, Ph.D. Julie Nelson Teresa Prendusi Laurie Davies Adams Worker honey bees (Apis mellifera) visiting almond blossoms (Prunus dulcis). Introduction Native bees are a hidden treasure. From alpine meadows in the national forests of the Rocky Mountains to the Sonoran Desert in the Coronado National Forest in Arizona and from the boreal forests of the Tongass National Forest in Alaska to the Ocala National Forest in Florida, bees can be found anywhere in North America, where flowers bloom. From forests to farms, from cities to wildlands, there are 4,000 native bee species in the United States, from the tiny Perdita minima to large carpenter bees. Most people do not realize that there were no honey bees in America before European settlers brought hives from Europe. These resourceful animals promptly managed to escape from domestication. As they had done for millennia in Europe and Asia, honey bees formed swarms and set up nests in hollow trees. -

Notes on the Nests of <I>Augochloropsis Metallica Fulgida

The Great Lakes Entomologist Volume 50 Numbers 1 & 2 -- Spring/Summer 2017 Article 4 Numbers 1 & 2 -- Spring/Summer 2017 September 2017 Notes on the Nests of Augochloropsis metallica fulgida and Megachile mucida in Central Michigan (Hymenoptera: Halictidae, Megachilidae) Jason Gibbs University of Manitoba, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation Gibbs, Jason 2017. "Notes on the Nests of Augochloropsis metallica fulgida and Megachile mucida in Central Michigan (Hymenoptera: Halictidae, Megachilidae)," The Great Lakes Entomologist, vol 50 (1) Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle/vol50/iss1/4 This Peer-Review Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biology at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Great Lakes Entomologist by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Notes on the Nests of Augochloropsis metallica fulgida and Megachile mucida in Central Michigan (Hymenoptera: Halictidae, Megachilidae) Cover Page Footnote My postdoctoral research in Michigan supported by the United States Department of Agriculture-National Institute for Food and Agriculture Specialty Crop Research Initiative; project 2012-01534: Developing Sustainable Pollination Strategies for U.S. Specialty Crops during this research. I also appreciate the willingness of Fenner Nature Center staff to allow research to be conducted on the Center’s grounds. This peer-review article is available in The Great Lakes Entomologist: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle/vol50/iss1/4 Gibbs: Halictid and megachilid bee nests of Central Michigan 2017 THE GREAT LAKES ENTOMOLOGIST 17 Notes on the Nests of Augochloropsis metallica fulgida and Megachile mucida in Central Michigan (Hymenoptera: Halictidae, Megachilidae) Jason Gibbs Department of Entomology, University of Manitoba, 12 Dafoe Rd., Winnipeg, MB, R3T 2N2. -

Bees on Alternative Flowering Plants on Vegetable Farms

Dr. Kimberly A. Stoner Department of Entomology The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station 123 Huntington Street, P. O. Box 1106 New Haven, CT 06504 Phone: (203) 974-8480 Fax: (203) 974-8502 Founded in 1875 Email: [email protected] Putting science to work for society Website: www.ct.gov/caes Bees on Alternative Flowering Plants on Vegetable Farms in Connecticut Pollination is essential for the production of many fruit, nut, and vegetable crops. Because honey bees have suffered major losses in recent years, there has been an increase in research on the many species of other wild bees present on farms, revealing their importance in pollinating crops. One recent worldwide survey of 41 different crops found that in most cases, while honey bees can supplement the pollination services of wild bees in increasing fruit set, they cannot adequately substitute for them (1). Wild bees cannot be moved from one place to another to find plants in bloom like honey bees, so they need a diversity of flowers as sources of nectar and pollen onsite throughout their lifespan (2). Many crops grown on vegetable farms benefit from bee pollination, including cucumbers, melons, pumpkins, squash, beans, tomatoes, and small fruit such as strawberries and raspberries (3). Many of these crops are visited more frequently by wild bees than by honey bees, including tomatoes, pepper, and watermelon (4). In my own research on pumpkins, in three years of studies, we have found that most of bee visits to pumpkin flowers are by wild bees rather than honey bees, and this has been confirmed by others (5,6,7). -

BITING, STINGING and VENOMOUS PESTS: INSECTS (For Non-Insects Such As Scorpions and Spiders, See Page 23)

BITING, STINGING AND VENOMOUS PESTS: INSECTS (For non-insects such as scorpions and spiders, see page 23). Bees include a large number of insects that are included in different families under the order Hymenoptera. They are closely related to ants and wasps, and are common and important components of outdoor community environments. Bees have lapping-type mouthparts, which enable them to feed on nectar and pollen from flowers. Most bees are pollinators and are regarded as beneficial, but some are regarded as pests because of their Pollination by honey bees stings, or damage that they cause due to Photo: Padmanand Madhavan Nambiar nesting activities. NOTABLE SPECIES Common name(s): Bee, honey bee Scientific name, classification: Apis spp., Order: Hymenoptera, Family: Apidae. Distribution: Worldwide. The western honey bee A. mellifera is the most common species in North America. Description and ID characters: Adults are medium to large sized insects, less than ¼ to Western honey bee, Apis mellifera slightly over 1 inch in length. Sizes and Photo: Charles J. Sharp appearances vary with the species and the caste. Best identifying features: Robust black or dark brown bodies, covered with dense hair, mouthparts (proboscis) can be seen extending below the head, hind pair of wings are smaller than the front pair, hind legs are stout and equipped to gather pollen, and often have yellow pollen-balls attached to them. Pest status: Non-pest, although some are aggressive and can sting in defense. Damage/injury: Usually none, and are regarded as the most beneficial insects. Swarming colonies near homes and buildings may cause concern, but they often move on. -

Understanding Habitat Effects on Pollinator Guild Composition in New York State and the Importance of Community Science Involvem

SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry Digital Commons @ ESF Dissertations and Theses Fall 11-18-2019 Understanding Habitat Effects on Pollinator Guild Composition in New York State and the Importance of Community Science Involvement in Understanding Species Distributions Abigail Jago [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.esf.edu/etds Part of the Environmental Monitoring Commons, and the Forest Biology Commons Recommended Citation Jago, Abigail, "Understanding Habitat Effects on Pollinator Guild Composition in New York State and the Importance of Community Science Involvement in Understanding Species Distributions" (2019). Dissertations and Theses. 117. https://digitalcommons.esf.edu/etds/117 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ ESF. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ ESF. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. UNDERSTANDING HABITAT EFFECTS ON POLLINATOR GUILD COMPOSITION IN NEW YORK STATE AND THE IMPORTANCE OF COMMUNITY SCIENCE INVOLVEMENT IN UNDERSTANDING SPECIES DISTRIBUTIONS By Abigail Joy Jago A thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science Degree State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry Syracuse, New York November 2019 Department of Environmental and Forest Biology Approved by: Melissa Fierke, Major Professor/ Department Chair Mark Teece, Chair, Examining Committee S. Scott Shannon, Dean, The Graduate School In loving memory of my Dad Acknowledgements I have many people to thank for their help throughout graduate school. First, I would like to thank my major professor, Dr. -

Evidence of Pollinators Foraging on Centipedegrass Inflorescences

insects Communication Evidence of Pollinators Foraging on Centipedegrass Inflorescences Shimat V. Joseph 1,* , Karen Harris-Shultz 2 and David Jespersen 3 1 Department of Entomology, University of Georgia, Griffin, GA 30223, USA 2 Crop Genetics and Breeding Research Unit, USDA-ARS, Tifton, GA 31793, USA; [email protected] 3 Department of Crop and Soil Science, University of Georgia, Griffin, GA 30223, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-770-228-7312 Received: 19 October 2020; Accepted: 10 November 2020; Published: 13 November 2020 Simple Summary: Turfgrasses are generally considered devoid of pollinators, as turfgrasses are often described as being only wind-pollinated. Centipede grass is a popular turfgrass grown in the southeastern USA. Centipede grass produces a large number of inflorescences from August to October each year. In a recent study, honeybees were found to collect pollen from centipede grass. However, it is not clear whether other pollinators are attracted to centipede grass inflorescences and actively forage them. Thus, the aim of the current study was to document the pollinators that foraged on centipede grass inflorescences. Pollinators visiting centipede grass were sampled using (1) a sweep net when actively foraging on an inflorescence; (2) blue, white and yellow pan traps; and (3) malaise or flight-intercept traps. Sweat-, bumble- and honeybees were captured while actively foraging on the centipede grass inflorescences. In the pan and flight-intercept traps, more sweat-bees were collected than honey- or bumblebees. We also captured hoverflies in the samples. The adult hoverflies consumed pollen during flower visits. This research is a first step toward developing bee-friendly lawns. -

A Preliminary Investigation of the Arthropod Fauna of Quitobaquito Springs Area, Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, Arizona

COOPERATIVE NATIONAL PARK RESOURCES STUDIES UNIT UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 125 Biological Sciences (East) Bldg. 43 Tucson, Arizona 85721 R. Roy Johnson, Unit Leader National Park Senior Research Scientist TECHNICAL REPORT NO. 23 A PRELIMINARY INVESTIGATION OF THE ARTHROPOD FAUNA OF QUITOBAQUITO SPRINGS AREA, ORGAN PIPE CACTUS NATIONAL MONUMENT, ARIZONA KENNETH J. KINGSLEY, RICHARD A. BAILOWITZ, and ROBERT L. SMITH July 1987 NATIONAL PARK SERVICE/UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA National Park Service Project Funds CONTRIBUTION NUMBER CPSU/UA 057/01 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction......................................................................................................................................1 Methods............................................................................................................................................1 Results ............................................................................................................................................2 Discussion......................................................................................................................................20 Literature Cited ..............................................................................................................................22 Acknowledgements........................................................................................................................23 LIST OF TABLES Table 1. Insects Collected at Quitobaquito Springs ...................................................................3 -

Observer Cards—Bees

Observer Cards Bees Bees Jessica Rykken, PhD, Farrell Lab, Harvard University Edited by Jeff Holmes, PhD, EOL, Harvard University Supported by the Encyclopedia of Life www.eol.org and the National Park Service About Observer Cards EOL Observer Cards Observer cards are designed to foster the art and science of observing nature. Each set provides information about key traits and techniques necessary to make accurate and useful scientific observations. The cards are not designed to identify species but rather to encourage detailed observations. Take a journal or notebook along with you on your next nature walk and use these cards to guide your explorations. Observing Bees There are approximately 20,000 described species of bees living on all continents except Antarctica. Bees play an essential role in natural ecosystems by pollinating wild plants, and in agricultural systems by pollinating cultivated crops. Most people are familiar with honey bees and bumble bees, but these make up just a tiny component of a vast bee fauna. Use these cards to help you focus on the key traits and behaviors that make different bee species unique. Drawings and photographs are a great way to supplement your field notes as you explore the tiny world of these amazing animals. Cover Image: Bombus sp., © Christine Majul via Flickr Author: Jessica Rykken, PhD. Editor: Jeff Holmes, PhD. More information at: eol.org Content Licensed Under a Creative Commons License Bee Families Family Name # Species Spheciformes Colletidae 2500 (Spheciform wasps: Widespread hunt prey) 21 Bees Stenotritidae Australia only Halictidae 4300 Apoidea Widespread (Superfamily Andrenidae 2900 within the order Widespread Hymenoptera) (except Australia) Megachilidae 4000 Widespread Anthophila (Bees: vegetarian) Apidae 5700 Widespread May not be a valid group Melittidae 200 www.eol.org Old and New World (Absent from S.