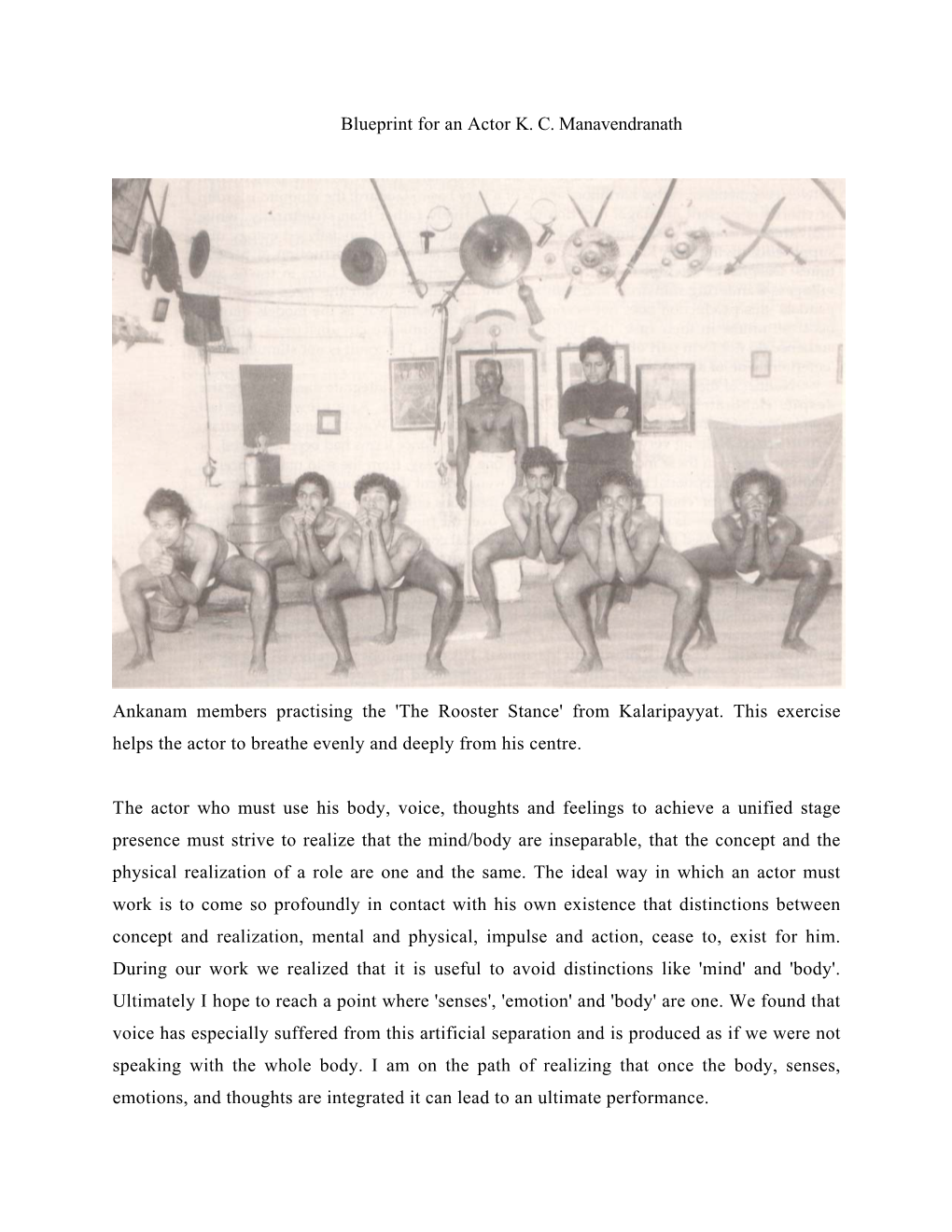

Blueprint for an Actor KC Manavendranath

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contents SEAGULL Theatre QUARTERLY

S T Q Contents SEAGULL THeatRE QUARTERLY Issue 17 March 1998 2 EDITORIAL Editor 3 Anjum Katyal ‘UNPEELING THE LAYERS WITHIN YOURSELF ’ Editorial Consultant Neelam Man Singh Chowdhry Samik Bandyopadhyay 22 Project Co-ordinator A GATKA WORKSHOP : A PARTICIPANT ’S REPORT Paramita Banerjee Ramanjit Kaur Design 32 Naveen Kishore THE MYTH BEYOND REALITY : THE THEATRE OF NEELAM MAN SINGH CHOWDHRY Smita Nirula 34 THE NAQQALS : A NOTE 36 ‘THE PERFORMING ARTIST BELONGED TO THE COMMUNITY RATHER THAN THE RELIGION ’ Neelam Man Singh Chowdhry on the Naqqals 45 ‘YOU HAVE TO CHANGE WITH THE CHANGING WORLD ’ The Naqqals of Punjab 58 REVIVING BHADRAK ’S MOGAL TAMSA Sachidananda and Sanatan Mohanty 63 AALKAAP : A POPULAR RURAL PERFORMANCE FORM Arup Biswas Acknowledgements We thank all contributors and interviewees for their photographs. 71 Where not otherwise credited, A DIALOGUE WITH ENGLAND photographs of Neelam Man Singh An interview with Jatinder Verma Chowdhry, The Company and the Naqqals are by Naveen Kishore. 81 THE CHALLENGE OF BINGLISH : ANALYSING Published by Naveen Kishore for MULTICULTURAL PRODUCTIONS The Seagull Foundation for the Arts, Jatinder Verma 26 Circus Avenue, Calcutta 700017 86 MEETING GHOSTS IN ORISSA DOWN GOAN ROADS Printed at Vinayaka Naik Laurens & Co 9 Crooked Lane, Calcutta 700 069 S T Q SEAGULL THeatRE QUARTERLY Dear friend, Four years ago, we started a theatre journal. It was an experiment. Lots of questions. Would a journal in English work? Who would our readers be? What kind of material would they want?Was there enough interesting and diverse work being done in theatre to sustain a journal, to feed it on an ongoing basis with enough material? Who would write for the journal? How would we collect material that suited the indepth attention we wanted to give the subjects we covered? Alongside the questions were some convictions. -

Copyright by Kristen Dawn Rudisill 2007

Copyright by Kristen Dawn Rudisill 2007 The Dissertation Committee for Kristen Dawn Rudisill certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: BRAHMIN HUMOR: CHENNAI’S SABHA THEATER AND THE CREATION OF MIDDLE-CLASS INDIAN TASTE FROM THE 1950S TO THE PRESENT Committee: ______________________________ Kathryn Hansen, Co-Supervisor ______________________________ Martha Selby, Co-Supervisor ______________________________ Ward Keeler ______________________________ Kamran Ali ______________________________ Charlotte Canning BRAHMIN HUMOR: CHENNAI’S SABHA THEATER AND THE CREATION OF MIDDLE-CLASS INDIAN TASTE FROM THE 1950S TO THE PRESENT by Kristen Dawn Rudisill, B.A.; A.M. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2007 For Justin and Elijah who taught me the meaning of apu, pācam, kātal, and tuai ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I came to this project through one of the intellectual and personal journeys that we all take, and the number of people who have encouraged and influenced me make it too difficult to name them all. Here I will acknowledge just a few of those who helped make this dissertation what it is, though of course I take full credit for all of its failings. I first got interested in India as a religion major at Bryn Mawr College (and Haverford) and classes I took with two wonderful men who ended up advising my undergraduate thesis on the epic Ramayana: Michael Sells and Steven Hopkins. Dr. Sells introduced me to Wendy Doniger’s work, and like so many others, I went to the University of Chicago Divinity School to study with her, and her warmth compensated for the Chicago cold. -

Mentors – Katha

Mentors – Katha about our work act now 300m storyshop .ST0{DISPLAY:NONE;} .ST1{DISPLAY:INLINE;} KATHA UTSAV MENTORS ARUNIMA MAZUMDAR, WRITER & JOURNALIST Arunima works with Roli Books, one of the foremost Indian publishing houses of India. She has worked as a journalist in the past and ABOUTcontinues to US write on arts, culturePROGRAMMES and travel for various publicationsQUICKLINKS such as The Hindu Business Line, Scroll, Femina, and Mumbai Mirror. Books are her best friend and she has keen interest in travel literature, written especially by Who we are 300M Donate Indian authors. Katha Books Katha Lab School Donate Books Storystop ILR Communities Volunteer ANKIT CHADHA – WRITER & STORYTELLER KATHA, A3, Sarvodaya Katha in the News ILR Government Schools Who we are Enclave, Sri AurobindoAnkit ChadhaWhat’s isour a writer-storytellerType whoKatha brings Utsav together performance, literatureWork With and Us history. He specializes in Dastangoi – the Marg, New Delhi - 110017art of Urdu storytelling, and has written, translated, compiled and performed stories under the direction of Mahmood Padho Pyar Se Contact Us Farooqui. His first book for children, the national award-winning My Gandhi Story was published by Tulika in 2013. © Copyright 2017. All Rights Reserved ARVIND GAUR Arvind Gaur, Indian director, is known for his work in innovative, socially and politically relevant theatre.Gaur’s plays are contemporary and thought-provoking, connecting intimate personal spheres of existence to larger social political issues. His work deals with Internet censorship, communalism, caste issues, feudalism, domestic violence, crimes of state, politics of power, violence, injustice, social discrimination, marginalization, and racism. Arvind is the leader of Asmita, Delhi‘s “most prolific theatre group”, and is an actor trainer, social activist, street theatre worker and story teller. -

Part 05.Indd

PART MISCELLANEOUS 5 TOPICS Awards and Honours Y NATIONAL AWARDS NATIONAL COMMUNAL Mohd. Hanif Khan Shastri and the HARMONY AWARDS 2009 Center for Human Rights and Social (announced in January 2010) Welfare, Rajasthan MOORTI DEVI AWARD Union law Minister Verrappa Moily KOYA NATIONAL JOURNALISM A G Noorani and NDTV Group AWARD 2009 Editor Barkha Dutt. LAL BAHADUR SHASTRI Sunil Mittal AWARD 2009 KALINGA PRIZE (UNESCO’S) Renowned scientist Yash Pal jointly with Prof Trinh Xuan Thuan of Vietnam RAJIV GANDHI NATIONAL GAIL (India) for the large scale QUALITY AWARD manufacturing industries category OLOF PLAME PRIZE 2009 Carsten Jensen NAYUDAMMA AWARD 2009 V. K. Saraswat MALCOLM ADISESHIAH Dr C.P. Chandrasekhar of Centre AWARD 2009 for Economic Studies and Planning, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. INDU SHARMA KATHA SAMMAN Mr Mohan Rana and Mr Bhagwan AWARD 2009 Dass Morwal PHALKE RATAN AWARD 2009 Actor Manoj Kumar SHANTI SWARUP BHATNAGAR Charusita Chakravarti – IIT Delhi, AWARDS 2008-2009 Santosh G. Honavar – L.V. Prasad Eye Institute; S.K. Satheesh –Indian Institute of Science; Amitabh Joshi and Bhaskar Shah – Biological Science; Giridhar Madras and Jayant Ramaswamy Harsita – Eengineering Science; R. Gopakumar and A. Dhar- Physical Science; Narayanswamy Jayraman – Chemical Science, and Verapally Suresh – Mathematical Science. NATIONAL MINORITY RIGHTS MM Tirmizi, advocate – Gujarat AWARD 2009 High Court 55th Filmfare Awards Best Actor (Male) Amitabh Bachchan–Paa; (Female) Vidya Balan–Paa Best Film 3 Idiots; Best Director Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots; Best Story Abhijat Joshi, Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots Best Actor in a Supporting Role (Male) Boman Irani–3 Idiots; (Female) Kalki Koechlin–Dev D Best Screenplay Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra, Abhijat Joshi–3 Idiots; Best Choreography Bosco-Caesar–Chor Bazaari Love Aaj Kal Best Dialogue Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra–3 idiots Best Cinematography Rajeev Rai–Dev D Life- time Achievement Award Shashi Kapoor–Khayyam R D Burman Music Award Amit Tivedi. -

Ghashiram Kotwal

FORUM GHASHIRAM KOTWAL K. Hariharan Seit dem ersten Jahr seines Bestehens hat das Forum sich bemüht, Indien 1977 Mani Kaul deutsch untertitelte Kopien der Festivalbeiträge herzustellen. Diese 107 Min. · DCP, 1:1.33 (4:3) · Farbe Praxis zahlt sich nun aus: Viele Filme haben so nur in Berlin überlebt, darunter GHASHIRAM KOTWAL, der nun in neuer, digitaler Fassung zur Regie K. Hariharan, Mani Kaul Wiederaufführung gelangt. Produziert hat ihn die Yukt Filmkooperati- Buch Vijay Tendulkar, nach seinem gleichnamigen Bühnenstück ve unter der Regie von K. Hariharan und Mani Kaul, basierend auf dem Kamera Mitglieder der Yukt Film gleichnamigen Theaterstück des Autors Vijay Tendulkar. Es beruht auf Cooperative der Biografie von Nana Phadnavis (1741–1800), eines einflussreichen Musik Bhaskar Chandavarkar Ministers, und beschreibt Entwicklung und Fall des Peshwa-Regimes in West-Indien vor dem Hintergrund einer Politik von Intrigen und Kor- Darsteller K. Hariharan Geboren 1952 in Chennai. Er ruption, die während der wachsenden kolonialen Bedrohung das Land Mohan Agashe (Nana) studierte am Film and TV Institute of India. verwüstete. Um seine Macht abzusichern, ernennt Nana Ghashiram Om Puri (Ghashiram Kotwal) Unter seiner Regie sind acht Spielfilme Mohan Gokhale sowie über 350 Dokumentar- und Kurzfilme zum Polizei- und Spionagechef des Staates. Nachdem er einst Unrecht erfahren und Rache geschworen hat, beginnt Ghashiram, willkürlich Rajni Chauhan entstanden. Darüber hinaus veranstaltete er Mitglieder der Theaterakademie Pune von 1995 bis 2004 Seminare zum indischen Macht gegen die brahmanische Bevölkerung auszuüben, bis diese seine Hinrichtung verlangt. Der Film entwickelt seine experimentelle Kino an der University of Pennsylvania. Zurzeit Produktion leitet er die LV Prasad Film & TV Academy in Ästhetik aus der Beschäftigung mit fiktionaler und dokumentarischer Yukt Film Cooperative Society Chennai, die 2004 gegründet wurde. -

New and Bestselling Titles Sociology 2016-2017

New and Bestselling titles Sociology 2016-2017 www.sagepub.in Sociology | 2016-17 Seconds with Alice W Clark How is this book helpful for young women of Any memorable experience that you hadhadw whilehile rural areas with career aspirations? writing this book? Many rural families are now keeping their girls Becoming part of the Women’s Studies program in school longer, and this book encourages at Allahabad University; sharing in the colourful page 27A these families to see real benefit for themselves student and faculty life of SNDT University in supporting career development for their in Mumbai; living in Vadodara again after daughters. It contributes in this way by many years, enjoying friends and colleagues; identifying the individual roles that can be played reconnecting with friendships made in by supportive fathers and mothers, even those Bangalore. Being given entrée to lively students with very little education themselves. by professors who cared greatly about them. Being treated wonderfully by my interviewees. What facets of this book bring-in international Any particular advice that you would like to readership? share with young women aiming for a successful Views of women’s striving for self-identity career? through professionalism; the factors motivating For women not yet in college: Find supporters and encouraging them or setting barriers to their in your family to help argue your case to those accomplishments. who aren’t so supportive. Often it’s submissive Upward trends in women’s education, the and dutiful mothers who need a prompt from narrowing of the gender gap, and the effects a relative with a broader viewpoint. -

Name of the Artist & Contact Details Links Grading

MINISTRY OF CULTURE FESTIVAL OF INDIA CELL PANEL OF ARTISTS/GROUPS FOR PARTICIPATION IN FESTIVALS OF INDIA ABROAD (O - OUTSTANDING, P- PROMISING, W- WAITING) Kathak S.NO Name of the Artist & contact Details Links Grading 1. Arijeet Mukherjee Business Development and Events Coordinator https://vimeo.com/151495589 Aditi Mangaldas Dance Company - The Drishtikon Dance Foundation Password: within123 O ADD: N-75/4/2, Sainik Farms South Lane - W 17 (Main) New Delhi-110080 MOB: 0 93111 57771 | 0 98105 66044 http://vimeo.com/aditimangaldasdance/ WEB: www.aditimangaldasdance.com Email: unchartedseas [email protected] Password: AMDC-US 2 Shovana Narayan IA&AS retd https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hha O Kathak Guru(Padmashri& central Sangeet Natak Akademi awardee) Mq0Nxg5s T2-LL-103, Commonwealth Games Village, Delhi-110092 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eOD Cell:+919811173734+919810725340 RnwLc9Mg Email:[email protected] or [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KAw Padmashree Awardee (1996) jM9ggTh8 SNA Awardee (1999-2000) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lsUd IJI0yn8 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aR W89rFJ6dc https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KAw jM9ggTh8 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UN A_4Cf1taQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Ax MxNkuxvw https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RhL 6wQ1Y-WA https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7A3 dh8pBElg https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Xe RJqb65e4 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xjsl5 Rq3HVo https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RJQ pWVKMTJI https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xjsl5 Rq3HVo https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Uf sLeqIYhY https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o- ftl8rIjnc https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jrnt MQy2320 https://i.ytimg.com/vi/IMKCvbQ7cUk/mq default.jpg https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MS wixkNxubg https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oO1 -WsLotZg https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gZrd 14SjJkA https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RJq PTQTD-Zs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PG5 -DTTykdk https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VW Fuv9mBUQI https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1UY NfMqZ9aQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SDq xUHbTLHw 3. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

President's Report

Vol. 57 No 47 June xx25 - June xx,30, 2016 President’s Report t feels like just yesterday that a group resounding success and will continue to of Rotarians took to their feet at my make a lasting impact on Bombay. The Installation to surprise everyone and Animal Committee was another active new shake things up with their flash mob initiative, working with the animal hospital Irendition of “Happy”. in Parel and with Welfare for Stray Dogs. And a happy year it has been. I have been We acted on our decision to be exacting on the recipient of so much affection and membership rules and unfortunately had to amazing support that this job has been a ask for the resignations of four members. wonderful experience. This past year 7 of our senior members passed away .We added a total of 12 new Preparations for the year began with an members; all of whom we hope will make April retreat in Pune with the Board of promising results. Our Talwada projects great contributions to the Club, resulting Directors, where much of the setting of have struggled with lack of water from in a total Club strength of 314. We have priorities and planning for the year was April onwards for the past few years; this actually seen a lowering of the average mapped out. This was an experiment — year, the deepening of the well and the age of our club.we started the year at an the first of its kind — but it was such a building of a new pipeline will ensure that average 58.9 and end it at 56.9. -

High Court of Delhi Advance Cause List

HIGH COURT OF DELHI ADVANCE CAUSE LIST LIST OF BUSINESS FOR TH THURSDAY,THE 20 FEBRUARY,2014 INDEX PAGES 1. APPELLATE JURISDICTION 1 TO 43 2. COMPANY JURISDICTION 44 TO 45 3. ORIGINAL JURISDICTION 46 TO 59 4. REGISTRAR GENERAL/ 60 TO 74 REGISTRAR(ORGL.)/ REGISTRAR (ADMN.)/ JOINT REGISTRARS(ORGL). 20.02.2014 1 (APPELLATE JURISDICTION) 20.02.2014 [Note : Unless otherwise specified, before all appellate side courts, fresh matters shown in the supplementary lists will be taken up first.] COURT NO. 1 (DIVISION BENCH-1) HON'BLE THE ACTING CHIEF JUSTICE HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE SIDDHARTH MRIDUL AFTER NOTICE MISC. MATTERS ____________________________ 1. FAO(OS) 429/2013 RAKESH TALWAR JAYANT K MEHTA,JAWAHAR RAJA CM APPL. 14852/2013 Vs. BINDU TALWAR CM APPL. 2546/2014 2. FAO(OS) 431/2013 BINDU TALWAR JAWAHAR RAJA CM APPL. 14934/2013 Vs. RAKESH TALWAR CM APPL. 2547/2014 3. FAO(OS) 23/2014 SHRI VIKAS AGGARWAL LEX INFINI,P D GUPTA AND CO Vs. SHRI BAL KRISHNA GUPTA AND ORS 4. LPA 417/2013 PREM RAJ N S DALAL,SHOBHNA Vs. LAND AND BUILDING TAKIAR,SIDHARTH PANDA DEPARTMENT AND ORS 5. LPA 444/2013 GIRI RAJ N S DALAL,SHOBHNA Vs. LAND AND BUILDING TAKIAR,YOGESH JAIN DEPARTMENT AND ORS 6. LPA 884/2013 PUNEET KAUSHIK AND ANR AYUSHI KIRAN,AMRIT PAL SINGH Vs. UNION OF INDIA AND ORS 7. W.P.(C) 6654/2011 YAHOO INDIA PVT LTD LUTHRA AND LUTHRA,MANEESHA Vs. UNION OF INDIA AND ANR DHIR,VAKUL SHARMA 8. W.P.(C) 6867/2013 RAGHU NANDAN SHARMA NEERAJ MALHOTRA,T.K. -

Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar's Castes in India

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT For the preparation of this SLM covering the Unit-2 of GE in accordance with the Model Syllabus, we have borrowed the content from the Wiki source, Internet Archive, free online encyclopaedia. Odisha State Open University acknowledges the authors, editors and the publishers with heartfelt thanks for extending their support. GENERIC ELECTIVE IN ENGLISH (GEEG) GEEG-2 Gender and Human Rights BLOCK-2 DR BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR'S CASTES IN INDIA UNIT 1 “ CASTES IN INDIA”: DR BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR UNIT 2 A TEXT ON CASTES IN INDIA”: DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR UNIT 1 : “CASTES IN INDIA”: DR BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR Structure 1.0 Objective 1.1 Introduction 1.2 B.R. Ambedkar 1.2.1 Early life 1.2.2 Education 1.2.3 Opposition to Aryan invasion theory 1.2.4 Opposition to untouchability 1.2.5 Political career 1.2.6 In Popular culture 1.3 Let us Sum up 1.4 Check Your Progress 1.0 OBJECTIVE In this unit we seeks to familiarize the students with issues of inequality, and oppression of caste and race . Points as follows: To analyse and interpret Ambedkar's ideological reflection on social and political aspects and on their reformation, in the light of the characteristics of the social and political order that prevailed in India during his life time and before. To assess the contribution made by Ambedkar as a social reformist, in terms of the development of the down trodden classes in India and with special reference to the Ambedkar Movement. To assess the services rendered by Ambedkar in his various official capacities, for the propagation and establishment of his messages. -

Documentation Kerala

DDOOCCUUMMEENNTTAATTIIOONN KKEERRAALLAA An index to articles in journals/periodicals available in the Legislature Library Vol. 12 (3) July – September 2017 SECRETARIAT OF THE KERALA LEGISLATURE THIRUVANANTHAPURAM DOCUMENTATION KERALA An index to articles in journals/periodicals available in the Legislature Library Vol.12(3) July to September 2017 Compiled by G. Maryleela, Chief Librarian V. Lekha, Librarian G. Omanaseelan., Deputy Librarian Denny.M.X, Catalogue Assistant Type Setting Sindhu.B, Computer Assistant BapJw \nbak`m sse{_dnbn e`yamb {][m\s¸« B\pImenI {]kn²oIcW§fn h¶n-«pÅ teJ-\-§-fn \n¶pw kmamPnIÀ¡v {]tbmP\{]Zhpw ImenI {]m[m\yapÅXpambh sXc-sª-Sp¯v X¿m-dm-¡nb Hcp kqNnIbmWv ""tUm¡psatâj³ tIcf'' F¶ ss{Xamk {]kn²oIcWw. aebmf `mjbnepw Cw¥ojnepapÅ teJ\§fpsS kqNnI hnjbmSnØm\¯n c−v `mK§fmbn DÄs¸Sp¯nbn«p−v. Cw¥ojv A£camem {Ia¯n {]tXyI "hnjbkqNnI' aq¶mw `mK¯pw tNÀ¯n«p−v. \nbak`m kmamPnIÀ¡v hnhn[ hnjb§fn IqSp-X At\z-jWw \S-¯m³ Cu teJ\kqNnI klmbIcamIpsa¶v IcpXp¶p. Cu {]kn²oIcWs¯¡pdn¨pÅ kmamPnIcpsS A`n{]mb§fpw \nÀt±i§fpw kzm-KXw sN¿p¶p. hn.-sI. _m_p-{]-Imiv sk{I«dn tIcf \nbak`. CONTENTS Pages Malayalam Section 01-36 English Section 37-57 Index 58-82 PART I MALAYALAM Aadhaar 4. CS-Xp-]£w tZiob t\Xr-Xz-¯n- te¡v Db-c-Ww. ]n. IrjvW-{]-kmZv 1. B[mdpw kzIm-cy-Xbpw Nn´, 7 Pqsse 2017, t]Pv 12þ15 sk_m-Ìy³ t]mÄ ImÀjnI {]Xn-k-Ônbpw ImÀjnI hn¹-h- tZim-`n-am-\n, 30 Pqsse 2017, ¯nsâ {]m[m-\yhpw hnh-cn-¡p¶ teJ-\w.