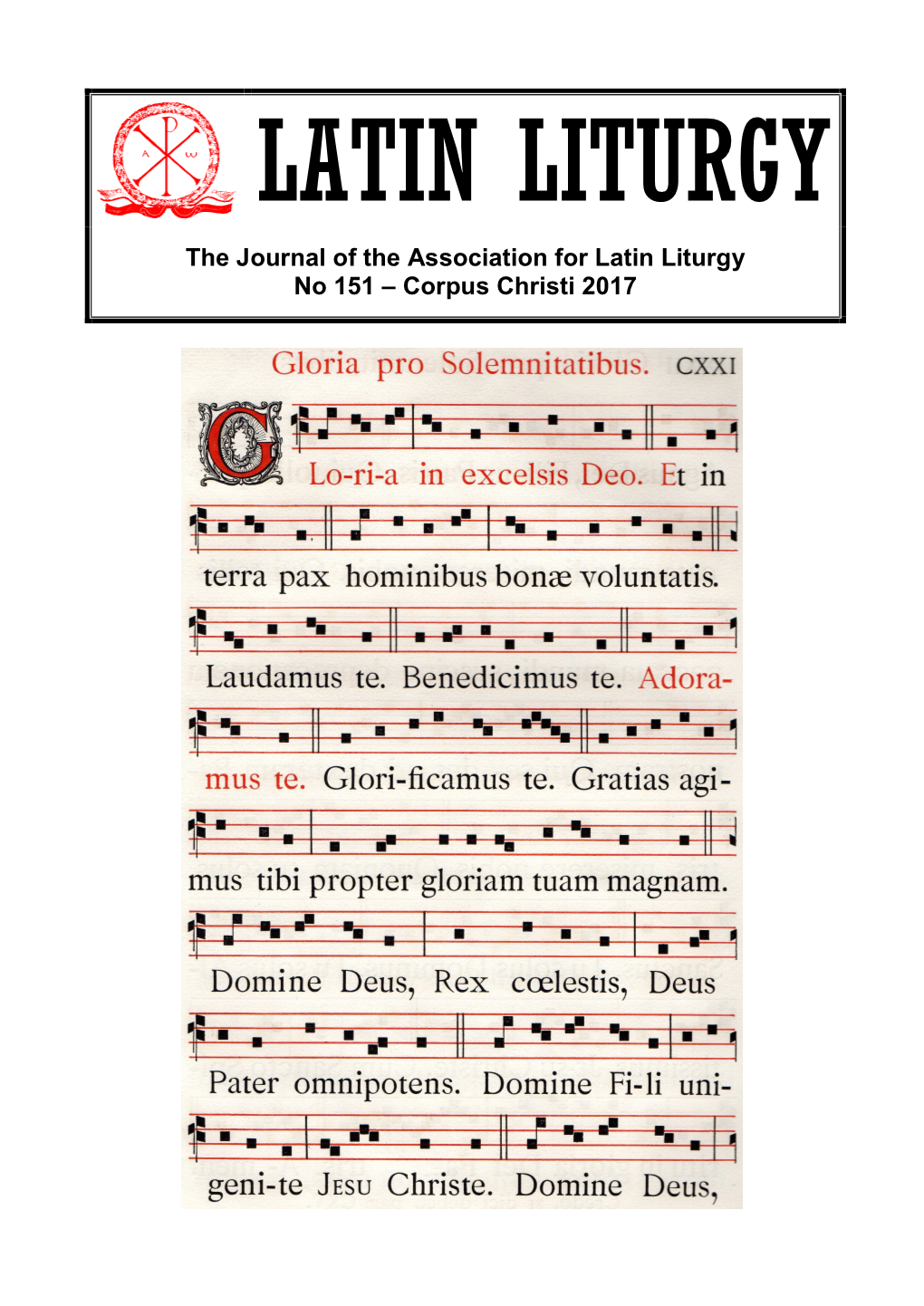

Corpus Christi 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

V Schools Adjudicator

Judgment Approved by the court for handing down. R (on the application of the Governing Body of the Oratory School) v The Schools Adjudicator, The British Humanist Association & Secretary of State for Education Neutral Citation Number: [2015] EWHC 1012 (Admin) Case No: CO/4693/2014 IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUSTICE QUEEN'S BENCH DIVISION ADMINISTRATIVE COURT Royal Courts of Justice Strand, London, WC2A 2LL Date: 17/04/2015 Before : MR JUSTICE COBB - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Between : The Queen Claimant On the application of The Governing Body of the London Oratory School - and - The Schools Adjudicator Defendant -and- (1) The British Humanist Association Interested (2) The Secretary of State for Education Parties - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Mr. Charles Béar QC & Mr. Julian Milford (instructed by Payne Hicks Beach) for the Claimants Mr. James Goudie QC & Ms Fiona Scolding (instructed by Treasury Solicitor) for the Defendant The First Interested Party was not represented Mr. Jonathan Moffett (instructed by Treasury Solicitor) for the Second Interested Party Hearing dates: 24-26 March 2015 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Approved Judgment Judgment Approved by the court for handing down. R (on the application of the Governing Body of the Oratory School) v The Schools Adjudicator, The British Humanist Association & Secretary of State for Education The Honourable Mr Justice Cobb: Introduction and Summary 1. By a Determination promulgated on 15 July 2014, School’s Adjudicator, Dr. Bryan Slater (“the Adjudicator”), concluded that the London Oratory School (“the School”) had been in breach of its statutory obligations in setting its admissions criteria for 2014 and 2015. By Claim dated 8 October 2014, the School challenges that Determination by way of judicial review; permission to pursue the Claim was granted on 10 November 2014. -

Hammersmith Academy Newsletter July 2019 Edition 6

HAMMERSMITH ACADEMY NEWSLETTER JULY 2019 EDITION 6 IN THIS EDITION: ITV NEWS Feature l STUDENT EXPLORERS l DON Giovanni REIMAGINED TEACHING EXCELLENCE l CHELSEA FLOWER SHOW l GREEN FOR GRENFELL l YEAR 11 PROM YEAR 9 RESIDENTIAL l DEPARTMENTAL NEWS l AND MORE! A WORD FROM OUR HEADTEACHER As you look through this edition of the Twinkle space mission. Year 8 The Academist newsletter, you will students presented a project at the see just how much we have packed Materials Matter Student Conference into this summer term. in Oxford. This is traditionally the busiest term, Our garden continues to bring with many of our students sitting in opportunities with our student GCSE and A Level exams. Yet, gardening team being invited by the this term has not just been wholly RHS to a young person's breakfast focused on examination results. We at the prestigious Chelsea Flower have still found the time to do the Show. Our students' love for growing incredibly important extra-curricular plants is now benefitting members elements which deliver a well of our borough with produce going rounded education. to the local foodbank. The positivity around our garden programme has There has been a real focus on even attracted the attention of ITV mathematics this term, starting News for National Gardening Week. with our new wall graphics to help our students remember important There has been an abundance formulas. We also hosted our first of individual successes this term, ever Maths Week London and saw both student and staff. Noor in Year our Year 9 students launch the 9 achieved a silver medal at the Santander 'The Numbers Game' English Schools' Athletics Association Roadshow. -

A Crisis Revisited: a Discussion of the Key Challenges Confronting Catholic Schools Today in the Light of Their History with Particular Reference to County Durham

Durham E-Theses Catholic schooling - a crisis revisited: a discussion of the key challenges confronting catholic schools today in the light of their history with particular reference to county Durham McCormack, Leo How to cite: McCormack, Leo (1996) Catholic schooling - a crisis revisited: a discussion of the key challenges confronting catholic schools today in the light of their history with particular reference to county Durham, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/5184/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 CO "Catholic Schooling - A Crisis Revisited". "A discussion of the key challenges confronting Catholic schools today in the light of their history with particular reference to County Durham". The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be pubUshed without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. -

Times Parent Power Schools Guide 2020

Times Parent Power Schools Guide 2020 Best Secondary Schools in London London’s grip on the very top of the Parent Power rankings for both state and independent schools has been loosened in the past 12 months. This time last year, the capital had 10 of the top 20 schools in the independent sector and nine of the top 20 state schools — figures that have declined this year to eight and five respectively. The overall number of London schools in both rankings has remained broadly the same, however, (down by just three in both the state and independent sectors) while the southeast region is dominant. The capital encompasses the best and worst of education. London primaries are hugely disproportionately represented in our primary school rankings, published last week, with 181 junior schools in the capital among the top 500. However, too many of the children from these schools go on to get lost in underachieving secondaries that are a million miles — or rather several hundred A*, A and B grades — away from the pages of Parent Power. There is cause for some optimism, however, as recent initiatives begin to bear fruit. New free schools, such as Harris Westminster Sixth Form, are helping to change the educational landscape. Harris Westminster is a partnership between Westminster School, one of the country’s most prestigious independents, and the Harris Federation, which has built up a network of 49 primary and secondary schools across the capital over the past 25 years, sponsored by Lord Harris, who built up the Carpetright empire. Harris Westminster sits fourth in our new ranking of sixth-form colleges, with 41% of students gaining at least AAB in two or more facilitating subjects — those that keep most options open at university, including, maths, English, the sciences, languages, history and geography. -

The London Oratory School

THE LONDON ORATORY SCHOOL SEND Policy and Information Report Approved by: The Governing Body Date: December 2020 Last reviewed on: December 2019 Next review due by: August 2021 THE LONDON ORATORY SCHOOL SPECIAL EDUCATIONAL NEEDS & DISABILITY POLICY 2020-21 S:\Deputy Folder\HMDATA\POLICIES\A-Z POLICIES\DFE REQUIRED\2020-21\SEND 2020.docx INTRODUCTION TO THE LONDON ORATORY SCHOOL The School was founded in 1863 by the Congregation of the Oratory of Saint Philip Neri, London, to serve Catholic families in London. It is now a Catholic Academy school for pupils between the ages of 7 and 18 and remains in the trusteeship of the Oratorians. Currently, there are 1367 pupils on roll. Since its foundation, the School has shared its religious and cultural identity with the Fathers of the London Oratory Church, which has its own very distinctive ethos and tradition of formal church worship and traditional Catholic music and culture, with an emphasis on the Latin liturgical tradition and its music, deriving from the first Oratory which was founded in 16th Century Rome. The School’s partnership with the Oratory Church is evident in the day-to-day life of the School and in its education and philosophy, its values and its expectations, strengthened through the chaplaincy work and regular contact with the Church. Parents are expected to be committed to and give their wholehearted support to Catholic education and to the distinctive religious and cultural traditions and ethos of the School. The School’s aim is to assist Catholic parents in fulfilling their obligations to educate their children in accordance with the principles and teachings of the Church and to do so within an environment that encourages and supports the spiritual, physical, moral and intellectual development of the child and help him to grow towards full Christian maturity; and to provide a wide and rich range of educational and cultural experiences which will encourage children to discover and develop their potential to its maximum and to strive for high standards of excellence in all activities. -

$ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $$ $ $ $ $ ±Projected Change In

Projected change in population aged 11 to 15 Change in population aged 11 to 15 2013 to 2023 ± 2013 to 2023* $19 -4I4s ltoin 2g1ton Abbey Road $20 21 to 47 Brent $21 47 to 84 Regent's Park Queen's Park Maida Vale Camden 84 to 130 Harrow 130 to 300 17 Road $ Little Church Golborne Venice $ Secondary Schools Street Bryanston $23 St. Charles Westbourne $16 and College Park and Old Oak $24 $14 Dorset Marylebone 1 Square High Street $ Bayswater Notting Colville Hyde Park Barns City Lancaster Gate West End 7 Ealing $ Pembridge Wormholt and White City Norland Westminster Shepherd's Bush Green Campden St. James' 12 Knightsbridge and Belgravia 15 $ Askew $ Holland $4 Addison Queen's Gate $25 Southwark Ravenscourt H&F RBK&C Brompton Ward $22 Park Abingdon Hans Town 10 $ Avonmore and 13 Vincent $8 Brook Green $ Warwick Earl's Courtfield Square Hammersmith Court * © GLA 2012 Round Broadway Tachbrook Hounslow $18 Demographic Projections, 2013 North End Royal Hospital Churchill Redcliffe Stanley Fulham Reach $9 Hammersmith and Fulham 13, Saint Thomas More Fulham Cremorne 1, Burlington Danes Academy 14, Sion-Manning RC Girls' School Broadway 2, Fulham College Boys' School 15, The Cardinal Vaughan School $3 3, Fulham Cross Girls' School Munster $11 4, Hammersmith Academy Westminster $2 Parsons 5, Hurlingham and Chelsea 16, King Solomon Academy Richmond Town Green 6, Lady Margaret School 17,L Paadmdinbgetotnh Academy $6 and 7, Phoenix High School 18, Pimlico Academy upon Thames Palace Walham Riverside 8, Sacred Heart High School 19, Quintin Kynaston School 9, The London Oratory School 20, St Augustine's CofE High School Sands End 10, West London Free School 21, St George's Catholic School 0 0.5 1 2 Kilometers $5 22, The Grey Coat Hospital WandswKeonrstinhgton and Chelsea settings 23, The St Marylebone CofE School 11, Chelsea Academy 24, Westminster Academy Prepared by Education Data Team 03/04/2013 12, Holland Park School 25, Westminster City School. -

Grand Final 2020

GRAND FINAL 2020 Delivered by In partnership with grandfinal.online 1 WELCOME It has been an extraordinary year for everyone. The way that we live, work and learn has changed completely and many of us have faced new challenges – including the young people that are speaking tonight. They have each taken part in Jack Petchey’s “Speak Out” Challenge! – a programme which reaches over 20,000 young people a year. They have had a full day of training in communica�on skills and public speaking and have gone on to win either a Regional Final or Digital Final and earn their place here tonight. Every speaker has an important and inspiring message to share with us, and we are delighted to be able to host them at this virtual event. A message from A message from Sir Jack Petchey CBE Fiona Wilkinson Founder Patron Chair The Jack Petchey Founda�on Speakers Trust Jack Petchey’s “Speak Out” Challenge! At Speakers Trust we believe that helps young people find their voice speaking up is the first step to and gives them the skills and changing the world. Each of the young confidence to make a real difference people speaking tonight has an in the world. I feel inspired by each and every one of them. important message to share with us. Jack Petchey’s “Speak Public speaking is a skill you can use anywhere, whether in a Out” Challenge! has given them the ability and opportunity to classroom, an interview or in the workplace. I am so proud of share this message - and it has given us the opportunity to be all our finalists speaking tonight and of how far you have come. -

The Best Education London Has to Offer

A FINE START YOUR GUIDE TO THE BEST SCHOOLS AND UNIVERSITIES IN LONDON THE BEST EDUCATION LONDON HAS TO OFFER Nurseries, schools and universities are not in short supply in Chelsea and Fulham. With London being recognised as a leading global centre for higher education, St George developments in West London have easy access to the local area’s best schools and the City’s many prestigious universities, providing a sound investment for children and the future. At primary level, schools like Thomas’s Battersea and Kensington Prep School offer children a well‑rounded education with Ofsted ratings of outstanding and excellent. Thomas’s Battersea’s most recent claim to fame is the arrival of Prince George as a student and with exceptional teaching staff and extensive facilities Thomas’s has very quickly become a popular school for boys and girls aged between 4‑13. Children tend to go on to equally prestigious schools like Eton, Harrow and Westminster. The range of local secondary schools is also impressive. There’s Godolphin & Latymer – a school praised as much for the niceness of their pupils as for their academic ability. St. Paul’s Girls’ School, meanwhile, is renowned for its musical department and academically, children perform highly with, on average, half the class feeding into Oxford and Cambridge and some of London’s world renowned universities such as King’s College and London School of Economics. Chelsea Creek is not only a stunning place to live, but offers a complete lifestyle and a way into some of the best education London has to offer. -

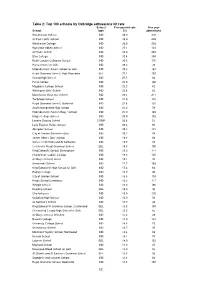

Table 2: Top 100 Schools by Oxbridge Admissions Hit Rate

Table 2: Top 100 schools by Oxbridge admissions hit rate School Five year hit rate Five year School type (%) admissions Westminster School IND 49.9 410 St Paul's Girls' School IND 49.0 225 Winchester College IND 36.0 230 Wycombe Abbey School IND 35.1 123 St Paul's School IND 33.0 259 Eton College IND 32.4 394 North London Collegiate School IND 30.5 176 Perse School for Girls IND 29.3 76 Haberdashers' Aske's School for Girls IND 29.3 164 Royal Grammar School, High Wycombe SEL 27.1 102 Oxford High School IND 25.5 84 Perse School IND 23.5 106 Magdalen College School IND 23.2 82 Withington Girls' School IND 22.6 82 Manchester Grammar School IND 22.4 211 Tonbridge School IND 21.9 148 Royal Grammar School, Guildford IND 21.6 135 South Hampstead High School IND 21.2 78 Haberdashers' Askes's Boys ' School IND 21.0 165 King's College School IND 20.9 152 London Oratory School COMP 20.6 53 Lady Eleanor Holles School IND 20.4 93 Abingdon School IND 20.3 121 City of London School for Girls IND 20.2 74 James Allen's Girls' School IND 19.8 84 School of St Helen and St Katharine IND 19.7 74 Colchester Royal Grammar School SEL 19.5 105 King Edward's School, Birmingham IND 19.3 111 Cheltenham Ladies' College IND 19.3 125 St Mary's School, Ascot IND 19.1 45 Sevenoaks School IND 17.7 169 King Edward VI High School for Girls IND 17.4 64 Radley College IND 16.7 96 City of London School IND 16.6 103 King's School Canterbury IND 16.3 117 Whitgift School IND 16.2 106 Reading School SEL 16.0 95 Charterhouse IND 16.0 120 Guildford High School IND 15.9 56 St Swithun's -

Hints and Tips Applying for a Primary School for Entry in September 2015

Hints and tips applying for a primary school for entry in September 2015 Apply online at: www.lbhf.gov.uk/eadmissions The Pan-London eAdmissions site opens on 1 September 2014. If your child was born between 1 September 2010 and 31 August 2011, you will need to apply for a primary school place by Thursday 15 January 2015. Hints and tips Contents The benefits of applying online 3 Where to obtain the information you need 4 Research, research, research! 5 Familiarise yourself with the admission criteria for schools 6 You can state up to six preferences 6 Take special care how you order your preferences 8 Do I need to provide additional information? 8 You must submit your application on time 8 Will I definitely be offered one of my preferences? 9 What happens to the preferences that I have not been offered? 9 Map of secondary schools in Hammersmith & Fulham 10 Contacting the School Admissions Team 12 Contact details 12 2 Apply online at: www.lbhf.gov.uk/eadmissions The benefits of applying online • It is quick and easy to do. • You can apply from any location with internet access, 24-hours-a- day, seven-days-a-week until the closing date of Thursday 15 January 2015. • You can log back on to change or delete preferences up until 11.59pm on the closing date. • You can register your mobile phone number to receive reminder alerts. • You are able to attach additional documents. • You will automatically receive a confirmation email, with your application reference number, once you submit your application. -

The London Oratory School

The London Oratory School Inspection Report Unique Reference Number 100365 LEA Hammersmith and Fulham LEA Inspection number 276296 Inspection dates 17 May 2006 to 18 May 2006 Reporting inspector Paul Dowgill This inspection was carried out under section 5 of the Education Act 2005. Type of school Secondary School address Seagrave Road School category Voluntary aided London Age range of pupils 7 to 18 SW6 1RX Gender of pupils Boys Telephone number 02073850102 Number on roll 1358 Fax number 02073817676 Appropriate authority The governing body Chair of governors Very Reverend Ignatius Harrison Date of previous inspection 20 March 2000 Headteacher Mr John McIntosh, OBE Age group Inspection dates Inspection number 7 to 18 17 May 2006 - 276296 18 May 2006 Inspection Report: The London Oratory School, 17 May 2006 to 18 May 2006 © Crown copyright 2006 Website: www.ofsted.gov.uk This document may be reproduced in whole or in part for non-commercial educational purposes, provided that the information quoted is reproduced without adaptation and the source and date of publication are stated. Further copies of this report are obtainable from the school. Under the Education Act 2005, the school must provide a copy of this report free of charge to certain categories of people. A charge not exceeding the full cost of reproduction may be made for any other copies supplied. Inspection Report: The London Oratory School, 17 May 2006 to 18 May 2006 1 Introduction The inspection was carried out by two of Her Majesty's Inspectors and four Additional Inspectors. Description of the school The London Oratory School is a popular, voluntary-aided Roman Catholic comprehensive school for boys aged 7-18 and girls aged 16-18. -

The London Oratory School Admissions Arrangements

THE LONDON ORATORY SCHOOL ADMISSIONS ARRANGEMENTS SEPTEMBER 2014 AIMS OF SCHOOL The School was founded by The Congregation of the Oratory of Saint Philip Neri (London) and the Fathers of this Congregation are the trustees of the School. The London Oratory School and The Brompton Oratory have always maintained a close working relationship which includes the Oratory Fathers supplying chaplaincy to the School and the School supplying the Schola choir for the parish. The School’s aim is to assist Catholic parents from across London in fulfilling their obligation to educate their children in accordance with the principles and teachings of the Church, to provide a unique liturgical life founded in the spiritual and musical traditions of the oratories of St Philip Neri and of the London Oratory Church; to do this within an environment which will encourage and support the spiritual, physical, moral and intellectual development of the child and help them to grow towards full Christian maturity; and to provide a wide and rich range of educational and cultural experiences which will encourage children to discover and develop their potential to its maximum and to strive for high standards of excellence in all activities. ARRANGEMENTS FOR ALL ADMISSIONS In these arrangements, “parent” means the parent or parents, or guardian, of the child (candidate) for whom a place at The London Oratory School is being sought. Where the plural “parents” is used, it refers both to the mother and the father of the candidate or to the guardian of the candidate. MEETINGS FOR PARENTS AND PROSPECTIVE PUPILS Parents are encouraged, accompanied if possible by their son/daughter, to attend one of the meetings for parents of prospective pupils, where the Headmaster and his staff will explain the nature of the School, the demands it makes of both pupils and their parents and the commitment which they make when they accept a place at the School.