Money and Elections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

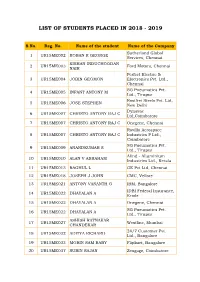

List of Students Placed in 2018 - 2019

LIST OF STUDENTS PLACED IN 2018 - 2019 S.No. Reg. No. Name of the student Name of the Company Sutherland Global 1 UR15ME002 ROBAN R GEORGE Services, Chennai KISHAN INDUCHOODAN 2 UR15ME003 Ford Motors, Chennai NAIR Perfect Electric & 3 UR15ME004 JOBIN GEOMON Electronics Pvt. Ltd., Chennai SG Pneumatics Pvt. 4 UR15ME005 INFANT ANTONY M Ltd., Tirupur Rostfrei Steels Pvt. Ltd, 5 UR15ME006 JOSE STEPHEN New Delhi Dynavac 6 UR15ME007 CHRISTO ANTONY RAJ C Ltd,Coimbatore 7 UR15ME007 CHRISTO ANTONY RAJ C Onegene, Chennai Ravilla Aerospace 8 UR15ME007 CHRISTO ANTONY RAJ C Industries P Ltd., Coimbatore SG Pneumatics Pvt. 9 UR15ME009 ANANDKUMAR S Ltd., Tirupur Alind - ALuminium 10 UR15ME010 ALAN V ABRAHAM Industries Ltd., Kerala 11 UR15ME013 RAGHUL L GE Pvt Ltd, Chennai 12 UR15ME018 JOSEPH J JOHN CMC, Vellore 13 UR15ME021 ANTONY VASANTH G IBM, Bangalore IDBI Federal Insurance, 14 UR15ME022 DHAYALAN A Erode 15 UR15ME022 DHAYALAN A Onegene, Chennai SG Pneumatics Pvt. 16 UR15ME022 DHAYALAN A Ltd., Tirupur ASHISH RATNAKAR 17 UR15ME027 Westline, Mumbai CHANDEKAR 24/7 Customer Pvt. 18 UR15ME032 ADITYA RICHARD Ltd., Bangalore 19 UR15ME033 MOBIN SAM BABY Flipkart, Bangalore 20 UR15ME037 SUBIN SAJAN Zengage, Coimbatore 21 UR15ME039 SIMON MONACHAN Westline, Mumbai Johnson Controls, 22 UR15ME040 JERRY ASHWATH J Chennai 23 UR15ME041 GRACE MARY Zengage, Coimbatore 24 UR15ME042 ARJUN M Electro Controls 25 UR15ME042 ARJUN M Onegene, Chennai 26 UR15ME045 NEVIN MATHEW BENJIE Zengage, Coimbatore 27 UR15ME047 SIVARAMAN ALAIS RAJA S Onegene, Chennai SG Pneumatics Pvt. 28 UR15ME047 SIVARAMAN ALAIS RAJA S Ltd., Tirupur 29 UR15ME049 GAUTHAM CHANDRA R Swiferz, Coimbatore 30 UR15ME050 VARUN V Onegene, Chennai 31 UR15ME052 JACOB THOMAS Adani Group, Gujarat SG Pneumatics Pvt. -

![226] Chennai, Monday, May 3, 2021 Chithirai 20, Pilava, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2052 Part V—Section 4](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7997/226-chennai-monday-may-3-2021-chithirai-20-pilava-thiruvalluvar-aandu-2052-part-v-section-4-387997.webp)

226] Chennai, Monday, May 3, 2021 Chithirai 20, Pilava, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2052 Part V—Section 4

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14 GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2021 [Price: Rs. 3.20 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE EXTRAORDINARY PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 226] CHENNAI, Monday, may 3, 2021 Chithirai 20, Pilava, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2052 Part V—Section 4 Notification by the Election Commission of India NOTIFICATION BY THE ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA NAMES OF MEMBERS NOTIFIED IN RESPECT OF THE tamil NADU legislative assembly AS NEWly CONSTITUTED. No. SRO G-29 /2021. The following Notification of the Election Commission of India, New Delhi-110 001, dated 3rd May, 2021 [13 Vaishakha, 1943 (Saka)] is published:- No.308/TN-LA/2021:- Whereas, in pursuance of Notification No. SRO D-1/2021 issued by the Governor of the State of Tamil Nadu on 12th March, 2021, under sub-section (2) of the Section 15 of the Representation of the People Act, 1951 (43 of 1951), a General Election has been held for the purpose of constituting a new Legislative Assembly for the State of Tamil Nadu; and Whereas, the results of the elections in all Assembly Constituencies in the said General Election have been declared by the Returning Officers concerned; Now, therefore, in pursuance of section 73 of the Representation of the People Act, 1951 (43 of 1951), the Election Commission of India hereby notifies the names of the Members elected for those constituencies, along with their party affiliation, if any , in the SCHEDULE to this Notification. (By Order) Malay Mallick, Secretary, Election Commission of India. SATYABRATA SAHOO, Secretariat, Chief Electoral Officer and Chennai-600 009, Principal Secretary to Government, 3rd May, 2021. -

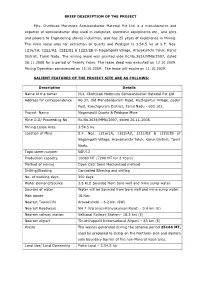

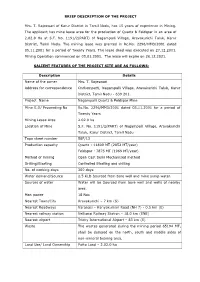

BRIEF DESCRIPTION of the PROJECT M/S. Chettinad Morimura

BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF THE PROJECT M/s. Chettinad Morimura Semiconductor Material Pvt Ltd is a manufacturer and exporter of semiconductor chip used in computer, electronic equipments etc., and grits and powers to Engineering stones industries, also has 25 years of experience in Mining. The mine lease area for extraction of Quartz and Feldspar is 3.54.5 ha at S.F. Nos. 1216/1A, 1222/A2, 1222/B2 & 1223/2B in Nagampalli Village, Aravakurichi Taluk, Karur District, Tamil Nadu. The mining lease was granted vide Rc.No.3624/MM6/2007, dated 26.11.2008 for a period of Twenty Years. The lease deed was executed on 12.10.2009. Mining Operation commenced on 15.10.2009. The lease will expire on 11.10.2029. SALIENT FEATURES OF THE PROJECT SITE ARE AS FOLLOWS: Description Details Name of the owner M/s. Chettinad Morimura Semiconductor Material Pvt Ltd Address for correspondence No.37, Old Mahabalipuram Road, Kazhipattur Village, padur Post, Kanchipuram District, Tamil Nadu - 603 103. Project Name Nagampalli Quartz & Feldspar Mine Mine G.O/ Proceeding No Rc.No.3624/MM6/2007, dated 26.11.2008 Mining Lease Area 3.54.5 ha Location of Mine S.F. Nos. 1216/1A, 1222/A2, 1222/B2 & 1223/2B of Nagampalli Village, Aravakurichi Taluk, Karur District, Tamil Nadu. Topo sheet number 58F/13 Production capacity 10080 MT (7200 MT for 2 Years) Method of mining Open Cast Semi Mechanized method Drilling/Blasting Controlled Blasting and drilling No. of working days 300 days Water demand/Source 2.5 KLD Sourced from bore well and mine sump water. -

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN – 2020 Page Chapter Title No

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN - 2020 Thiru. T.ANBALAGAN, I.A.S Chairman & District Collector District Disaster Management Authority, Karur District. District at a Glance S.No Facts Data 1 District Existence 25.07.1996 2 Latitude 100 45 N’ and 110 45 3 Longitude 770 45’ and 780 07’ 4 Divisions (2) Karur, Kulithalai 5 Taluks (7) Karur , Aravakurichi, Kulithalai,Pugalur Krishnarayapuram,Kadavur ,Manmangalam 6 Firkas 20 7 Revenue Villages 203 8 Municipalities (2) Karur Kulithalai 9 Panchayat Unions (8) Karur ,Thanthoni Aravakurichi,K.Paramathi Kulithalai ,Thogamalai, Krishnarayapuram, Kadavur 10 Town Panchayats (11) Punjaipugalur,Punjai thottakurichi Kagithapuram,Puliyur Uppidamangalam,Pallapatti Aravakurichi,Maruthur Nangavaram,Palaiyajayakondam Cholapuram,Krishnarayapuram 11 Village Panchayats 157 12 Area (Sq.kms) 2895.6 13 Population Persons Males Females 1064493 528184 536309 14 Population Density (Sq.kms) 368 15 Child (0 – 6 age) Persons Males Females 98980 50855 48125 15 Child (0 – 6) Sex Ratio 946 17 Literates Persons Males Females 727044 401726 325318 DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN – 2020 Page Chapter Title No. I Profile of the District 1 II District Disaster Management Plan (DDMP) 15 Hazard, Vulnerability, Capacity and Risk III 24 Assessment IV Institutional Mechanism 53 V Preventive and Mitigation Measures 61 VI Preparedness Measures 70 VII Response, Relief and Recovery Measures 88 Coordination Mechanism for Implementation of VIII 95 DDMP Standard Operating Procedures (sops) and Check IX 104 List x Sendai Framework Project -

TAMILNADU NAME of the DISTRICT : CHENNAI Division: Thiruvanmiyur 1 Hotel Saravana Bhavan Hotel Saravana Bhavan, Perungudi, Chennai-96

DETAILS OF DHABA'S IN TAMILNADU NAME OF THE DISTRICT : CHENNAI Division: Thiruvanmiyur 1 Hotel Saravana Bhavan Hotel Saravana Bhavan, Perungudi, Chennai-96. 7823973052 2 Hotel Hot Chips Hotel Hot Chips, ECR Road, Chennai-41 044-2449698 3 Yaa Moideen Briyani Yaa Moideen Briyani, ECR Road, Chennai-41 044-43838315 4 Kuppana Hotel Junior Kuppana, OMR, Chennai-96 044-224545959 Sree Madurai Devar Hotel, Porur Toll-8, NH Road 5 Sree Madurai Devar Hotel 72993 87778 Porur, Toll Gate Vanagarm, Porur, Chennai. Hotel Madurai Pandiyan, Porur Toll No.49, Bye Pass 6 Hotel Madurai Pandiyan road, Om sakthi nager, Maduravoyal, NR Tool Gate, 98841 83534 Chennai-95. Briyani Dream Porur Toll-39, Om Sakthi Nager, Porur 7 Briyani Dream 75500 60033 road, Chennai-95. Hotel Bypass Orient Porur Toll Bo.12B, Swami 8 Hotel BypassOrient 98411 92606 Vivekandar road bypass, Chennai-116 District: KANCHIPURAM Division : Kanchipuram New Panjabi Dhaba, Chennai to Bengalure Highway, 9 Rajendiran 9786448787 Rajakulam, Kanchipuram New Punjabi Dhaba, Chennai to Bengalure Highway, 10 Rajendiran 9786448787 Vedal, Kanchipuram, 9080772817 11 Punjab Dhaba Punjabi Dhaba, White Gate, Kanchipuram 9600407219 12 JP Hotels J P Hotels, Baluchettichatram, Kanchipuram, Hotel Sakthi Ganapathi, White Gate, Chennai to 13 Sakthi Ganapathi Hotel 9003855555 Bengalure Highway, Kanchipuram Hotel Ramanas, Chennai to Bengalure Highway, 14 Guru 9443311222 Kilambi, Kanchipuram Division: TAMBARAM AL-Taj Hotel, GST Road, Peerkan karanai, Chennai- 15 K.Thameem Ansari 9840687210 63 Division: SRIPERUMBUTHUR -

List of Blocks of Tamil Nadu District Code District Name Block Code

List of Blocks of Tamil Nadu District Code District Name Block Code Block Name 1 Kanchipuram 1 Kanchipuram 2 Walajabad 3 Uthiramerur 4 Sriperumbudur 5 Kundrathur 6 Thiruporur 7 Kattankolathur 8 Thirukalukundram 9 Thomas Malai 10 Acharapakkam 11 Madurantakam 12 Lathur 13 Chithamur 2 Tiruvallur 1 Villivakkam 2 Puzhal 3 Minjur 4 Sholavaram 5 Gummidipoondi 6 Tiruvalangadu 7 Tiruttani 8 Pallipet 9 R.K.Pet 10 Tiruvallur 11 Poondi 12 Kadambathur 13 Ellapuram 14 Poonamallee 3 Cuddalore 1 Cuddalore 2 Annagramam 3 Panruti 4 Kurinjipadi 5 Kattumannar Koil 6 Kumaratchi 7 Keerapalayam 8 Melbhuvanagiri 9 Parangipettai 10 Vridhachalam 11 Kammapuram 12 Nallur 13 Mangalur 4 Villupuram 1 Tirukoilur 2 Mugaiyur 3 T.V. Nallur 4 Tirunavalur 5 Ulundurpet 6 Kanai 7 Koliyanur 8 Kandamangalam 9 Vikkiravandi 10 Olakkur 11 Mailam 12 Merkanam Page 1 of 8 List of Blocks of Tamil Nadu District Code District Name Block Code Block Name 13 Vanur 14 Gingee 15 Vallam 16 Melmalayanur 17 Kallakurichi 18 Chinnasalem 19 Rishivandiyam 20 Sankarapuram 21 Thiyagadurgam 22 Kalrayan Hills 5 Vellore 1 Vellore 2 Kaniyambadi 3 Anaicut 4 Madhanur 5 Katpadi 6 K.V. Kuppam 7 Gudiyatham 8 Pernambet 9 Walajah 10 Sholinghur 11 Arakonam 12 Nemili 13 Kaveripakkam 14 Arcot 15 Thimiri 16 Thirupathur 17 Jolarpet 18 Kandhili 19 Natrampalli 20 Alangayam 6 Tiruvannamalai 1 Tiruvannamalai 2 Kilpennathur 3 Thurinjapuram 4 Polur 5 Kalasapakkam 6 Chetpet 7 Chengam 8 Pudupalayam 9 Thandrampet 10 Jawadumalai 11 Cheyyar 12 Anakkavoor 13 Vembakkam 14 Vandavasi 15 Thellar 16 Peranamallur 17 Arni 18 West Arni 7 Salem 1 Salem 2 Veerapandy 3 Panamarathupatti 4 Ayothiyapattinam Page 2 of 8 List of Blocks of Tamil Nadu District Code District Name Block Code Block Name 5 Valapady 6 Yercaud 7 P.N.Palayam 8 Attur 9 Gangavalli 10 Thalaivasal 11 Kolathur 12 Nangavalli 13 Mecheri 14 Omalur 15 Tharamangalam 16 Kadayampatti 17 Sankari 18 Idappady 19 Konganapuram 20 Mac. -

1. Introduction

1. Introduction:- In pursuance to the Gazette Notification, Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, the Government of India Notification No. S.O.3611 (E) dated 25.07.2018 laidprocedure for preparation of District Survey Report of minor minerals other than sand mining or river bed mining. The main purpose of preparation of District Survey Report is to identify the mineral resources and developing the mining activities along with other relevant data of the District . District Survey Report, Karur District Page 1 2. Overview of Mining Activity in the District:- The Karur District forms part of the Archean complex of penisular gneiss. The general rock types of this area are Charnockite, Biotite gneiss, Migmatites and Anorthosites. Karur District is blessed with good reserves of Crystalline Limestone known as “ Palayam belt ” in Varavanai, Thennilai, Gudalur etc., villages in Kulithalai Taluk and the occurrences of good quality of pegmatite veins constituting with glassy Quartz and potash Feldspar in lensoid patches in Nagampalli and Pungambadi areas in Aravakurichi Taluk. The major mineral such as Limestone, Quartz and Feldspar and Magnesite and Duniteare exploited in Karur District and utilized in the mineral based industries. The Charnockite and Granite Gneiss rocks are found to occur in K.Paramathi, Athur, Thennilai, Punnam, Kuppam, Munnur, Karudayampalayam, Anjur villages in Karur and Aravakurichi Taluk are exploited to produce building materials and road metal (Jelly) and over burden soil appear as gray to reddish in colour called as graval. The commercially known “ ColoumboZubrana ” the unique type in the Multicoloured Granite / Granite Gneiss category is occurring in Thogamalai, Naganur and Kazhugur Villages in Kulithalai Taluk. -

List of Polling Stations for 134 Aravakurichi Assembly Segment Within the 23 Karur Parliamentary Constituency

List of Polling Stations for 134 Aravakurichi Assembly Segment within the 23 Karur Parliamentary Constituency Sl.No Polling Location and name of building in Polling Areas Whether for All station No. which Polling Station located Voters or Men only or Women only 12 3 4 5 1 1 Panchayat Union.Middle.School, 1.Anjur (R.V) and (P) Kolakkaranpalayam ward 2 , 2.Anjur (R.V) and (P) All Voters Eastern Building Narikattuvalasu Ward 2 , 3.Anjur (R.V) and (P) Karuvayampalayam Ward 2,3 , ,Pandilingapuram H/o Anjur- 4.Anjur (R.V) and (P) Pandipalayam Ward 3 , 5.Anjur (R.V) and (P) 638151 Karuvayampalayam Murungakadu Ward 3 , 6.Anjur (R.V) and (P) Pandilingapuram Ward 3 , 7.Anjur (R.V) and (P) Pandilingapuram Gandhinagar Colony Ward 3 , 8.Anjur (R.V) and (P) Kolanthapalayam Nanthanar Colony Ward 3 , 9.Anjur (R.V) and (P) Kolanthapalayam Ward 3 , 10.Anjur (R.V) and (P) Kolanthapalayam Bajar Street Ward 3 , 11.Anjur (R.V) and (P) Velauthampalayam Ward 3 , 12.Anjur (R.V) and (P) Velauthampalayam Saliankattupallam Ward 3 2 2 Panchayat Union.Ele.School, 1.Anjur (RV) and (P) Valaiyapalayam ward 1 , 2.Anjur (RV) and (P) All Voters West Facing Building Chinnavalaiyapalayam Athidiravidar Street Ward 1 , 3.Anjur (RV) and (P) ,Kuppagoundanvalasu H/o.Anjur - Chinnavalaiyapalayam Ward 1 , 4.Anjur (RV) and (P) Chinnavalaiyapalayam 638151 Vaiykalmedu Athidiravidar St. W 1 , 5.Anjur (RV) and (P) Chinnavalaiyapalayam Velliankattuvalasu W1 , 6.Anjur (RV) and (P) Chinnavalaiyapalayam Molakadu Ward 1 , 7.Anjur (RV) and (P) Papavalasu Onjakadu Ward 1 , 8.Anjur (RV) and (P) Papavalasu Athidiravidar Colony Ward 1 , 9.Anjur (RV) and (P) Papavalasu Ward 1 , 10.Anjur (RV) and (P) Papavalasu Southvalavu Ward 1 , 11.Anjur (RV) and (P) Pillapalayam Adhidravidar Colony Ward 4 , 12.Anjur (RV) and (P) Pillapalayam Ward 4 , 13.Anjur (RV) and (P) Pillapalayam Periyakadu Ward 4 Page Number : 1 of 81 List of Polling Stations for 134 Aravakurichi Assembly Segment within the 23 Karur Parliamentary Constituency Sl.No Polling Location and name of building in Polling Areas Whether for All station No. -

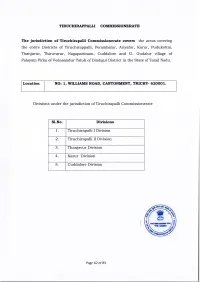

Trichy, Location Tamilnadu

TIRUCHIRAPPALLI COMMISSIONERATE The jurisdiction of Tinrchirapalli Commissionerate covers the areas covering the entire Districts of Tiruchirappalli, Perambalur, Ariyalur, Karur, Pudukottai, Thanjavur, Thiruvarur, Nagapattinarn, Cuddalore and D. Gudalur village of Palayam Firka of Vedasandur Taluk of Dindigul District in the State of Tamil Nadu. Location I NO: 1, WILLIAMS ROAD, CANTONMENT, TRICI{Y- 620001. Divisions under the jurisdiction of Tiruchirapalli Commissionerate Sl.No. Divisions 1. Tiruchirapalli I Division 2. Tiruchirapalli II Division 3. Thanjavur Division 4. Karur Division 5. Cuddalore Division Pagc 62 of 83 1. Tiruchirappalli - I Division of Tiruchirapalli Commissionerate. 1st Floor, 'B'- Wing, 1, Williams Road, Cantonment, Trichy, Location Tamilnadu. PIN- 620 OOL. Areas covering Trichy District faltng on the southern side of Jurisdiction Kollidam river, Mathur, Mandaiyoor, Kalamavoor, Thondaimanallur and Nirpalani villages of Kolathur Taluk and Viralimalai Taluk of Pudukottai District. The Division has seven Ranges with jurisdiction as follows: Name of the Location Jurisdiction Range Areas covering Wards No. 7 to 25 of City - 1 Range Tiruchirappalli Municipal Corporation Areas covering Wards No.27 to 30, 41, 42, City - 2 Range 44, 46 to 52 of Tiruchirappalli Municipal l"t Floor, B- Wing, 1, Corporation Williams Road, Areas covering Wards No. 26, 31 to 37 43, Cantonment, Trichy, PIN , 54 to 60 of Tiruchirappalli Municipal 620 00L. Corporation; and Sempattu village of Trichy Taluk, Gundur, Sooriyur villages of City - 3 Range Tiruverumbur Taluk of Trichy District, Mathur, Mandaiyur, Kalamavoor, Thondamanallur, Nirpalani Village of Kulathur Taluk of Pudukottai District. Areas covering Wards No. 63 to 65 of Civil Maintenance Tiruverumbur Tiruchirappalli Municipal Corporation and Building, Kailasapuram, Range Navalpattu and Vengur villages of Trichy, PIN 620 OI4. -

BRIEF DESCRIPTION of the PROJECT Mrs. T. Rajeswari Of

BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF THE PROJECT Mrs. T. Rajeswari of Karur District in Tamil Nadu, has 15 years of experience in Mining. The applicant has mine lease area for the production of Quartz & Feldspar in an area of 2.02.0 Ha at S.F. No. 1191/2(PART) of Nagampalli Village, Aravakurichi Taluk, Karur District, Tamil Nadu. The mining lease was granted in Rc.No. 2296/MM3/2001 dated 05.11.2001 for a period of Twenty Years. The lease deed was executed on 27.12.2001. Mining Operation commenced on 05.01.2001. The lease will expire on 26.12.2021. SALIENT FEATURES OF THE PROJECT SITE ARE AS FOLLOWS: Description Details Name of the owner Mrs. T. Rajeswari Address for correspondence Onthempatti, Nagampalli Village, Aravakurichi Taluk, Karur District, Tamil Nadu - 639 201. Project Name Nagampalli Quartz & Feldspar Mine Mine G.O/ Proceeding No Rc.No. 2296/MM3/2001 dated 05.11.2001 for a period of Twenty Years Mining Lease Area 2.02.0 ha Location of Mine S.F. No. 1191/2(PART) of Nagampalli Village, Aravakurichi Taluk, Karur District, Tamil Nadu Topo sheet number 58F/13 Production capacity Quartz : 11809 MT (2952 MT/year) Feldspar : 7875 MT (1969 MT/year) Method of mining Open Cast Semi Mechanized method Drilling/Blasting Controlled Blasting and drilling No. of working days 300 days Water demand/Source 2.5 KLD Sourced from bore well and mine sump water. Sources of water Water will be Sourced from bore well and wells of nearby area. Man power 18 Nos Nearest Town/City Aravakurichi – 7 km (S) Nearest Roadways Varanasi – Kanyakumari Road (NH 7) - 0.5 km (E) Nearest railway station Vellianai Railway Station – 18.0 km (ENE) Nearest airport Trichy International Airport – 83 km (E) Waste The wastes generated during the mining period 65194 MT, shall be dumped on the north, south and middle sides of non-mineral bearing area. -

A Study of Personnel Management Perspectives of Higher Secondary School Teachers in Karur District, Tamil Nadu

A STUDY OF PERSONNEL MANAGEMENT PERSPECTIVES OF HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL TEACHERS IN KARUR DISTRICT, TAMIL NADU Thesis Submitted to Bharathidasan Univesity, Tiruchirappalli in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Award of the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN ECONOMICS Research Scholar Mr. V. RAMACHANDRAN (Ref.No:11009/Ph.D2)/Economics/P.T/July2009) Research Supervisor Dr. R.VEERASEKARAN, M.A., M.Phil., Ph.D., BLIS., Formerly Associate Professor & Research Advisor PG & Research Department of Economics Urumu Dhanalakshmi College (Nationally Re-Accredited with “A” Grade by NAAC) Tiruchirappalli- 620019. Director, Mohd. Sathak Group of Institutions Solinganallur, Chennai – 600 119. TAMILNADU - INDIA PG and Research Department of Economics Urumu Dhanalakshmi College (Nationally Re-Accredited with “A” Grade by NAAC) Tiruchirappalli- 620019 TAMILNADU - INDIA. OCTOBER 2014 Certificate Certificate Certificate Dr. R.VEERASEKARAN, M.A., M.Phil., Ph.D., BLIS., Formerly Associate Professor & Research Advisor PG & Research Department of Economics Urumu Dhanalakshmi College (Nationally Re-Accredited with “A” Grade by NAAC) Tiruchirappalli- 620019. Director, Mohd. Sathak Group of Institutions Solinganallur, Chennai – 600 119. TAMILNADU - INDIA Date: CERTIFICATE This is to certify that the thesis entitled “A STUDY OF PERSONNEL MANAGEMENT PERSPECTIVES OF HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL TEACHERS IN KARUR DISTRICT, TAMIL NADU” submitted to the Bharathidasan University, Tiruchirappalli for the award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Economics is a bonafide and original work done by Mr. V. RAMACHANDRAN under my supervision and guidance. The thesis has not been submitted to any other university or institution for the award of any Degree, Diploma, Associate ship, Fellowship, or any other Title. Signature of the Guide Dr. -

Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly

PREFACE TAMIL NADU LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY (Thirteenth Assembly) This publication contains a brief resume of the business transacted by the Thirteenth Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly during its First Session, held from 17th May, 2006 to 31st May, 2006. FIRST SESSION (17th May, 2006 to 31st May, 2006) Chennai-600 009. M. SELVARAJ, Dated: -10-2006. SECRETARY. RESUME OF BUSINESS Legislative Assembly Secretariat, Chennai - 600 009. CONTENTS -1- TAMIL NADU LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Serial Subject Page THIRTEENTH ASSEMBLY - FIRST SESSION Number RESUME OF WORK TRANSACTED BY THE TAMIL NADU I. Summons 1 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FROM 17TH MAY, 2006 II. Duration of the Meeting 1 TO 31ST MAY, 2006. III. Sittings of the Assembly 1 The Thirteenth Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly was constituted on the IV. Prorogation 1 12th May, 2006 after the General Elections held to the Tamil Nadu Legislative Assembly on the 8th May, 2006. V. Appointment of Speaker Pro-tem 2 VI. Oath or Affirmation 2 I. SUMMONS VII. Election of Speaker and Deputy Speaker 3 Summons for the First Session of the Thirteenth Tamil Nadu Legislative VIII. Appointment of Leader of the House, 4 Assembly were issued to the Members of the Legislative Assembly on the 13th Chief Government Whip and the May 2006 in S.O.Ms.No. 68, Legislative Assembly Secretariat, dated the 13th Recognition of Leader of the Opposition May, 2006 to meet at 9.30 a.m on the 17th May, 2006. IX. Obituary References 5 II. DURATION OF THE MEETING X. Condolence Resolutions 6 The First Session of the Thirteenth Legislative Assembly commenced on XI.