Steatitis in Fish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hemiscyllium Ocellatum), with Emphasis on Branchial Circulation Kåre-Olav Stensløkken*,1, Lena Sundin2, Gillian M

The Journal of Experimental Biology 207, 4451-4461 4451 Published by The Company of Biologists 2004 doi:10.1242/jeb.01291 Adenosinergic and cholinergic control mechanisms during hypoxia in the epaulette shark (Hemiscyllium ocellatum), with emphasis on branchial circulation Kåre-Olav Stensløkken*,1, Lena Sundin2, Gillian M. C. Renshaw3 and Göran E. Nilsson1 1Physiology Programme, Department of Molecular Biosciences, University of Oslo, PO Box 1041, NO-0316 Oslo Norway and 2Department of Zoophysiology, Göteborg University, SE-405 30 Göteborg, Sweden and 3Hypoxia and Ischemia Research Unit, School of Physiotherapy and Exercise Science, Griffith University, PMB 50 Gold coast Mail Centre, Queensland, 9726 Australia *Author for correspondence (e-mail: [email protected]) Accepted 17 September 2004 Summary Coral reef platforms may become hypoxic at night flow in the longitudinal vessels during hypoxia. In the during low tide. One animal in that habitat, the epaulette second part of the study, we examined the cholinergic shark (Hemiscyllium ocellatum), survives hours of severe influence on the cardiovascular circulation during severe hypoxia and at least one hour of anoxia. Here, we examine hypoxia (<0.3·mg·l–1) using antagonists against muscarinic the branchial effects of severe hypoxia (<0.3·mg·oxygen·l–1 (atropine 2·mg·kg–1) and nicotinic (tubocurarine for 20·min in anaesthetized epaulette shark), by measuring 5·mg·kg–1) receptors. Injection of acetylcholine (ACh; –1 ventral and dorsal aortic blood pressure (PVA and PDA), 1·µmol·kg ) into the ventral aorta caused a marked fall in heart rate (fH), and observing gill microcirculation using fH, a large increase in PVA, but small changes in PDA epi-illumination microscopy. -

Respiratory Disorders of Fish

This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/copyright Author's personal copy Disorders of the Respiratory System in Pet and Ornamental Fish a, b Helen E. Roberts, DVM *, Stephen A. Smith, DVM, PhD KEYWORDS Pet fish Ornamental fish Branchitis Gill Wet mount cytology Hypoxia Respiratory disorders Pathology Living in an aquatic environment where oxygen is in less supply and harder to extract than in a terrestrial one, fish have developed a respiratory system that is much more efficient than terrestrial vertebrates. The gills of fish are a unique organ system and serve several functions including respiration, osmoregulation, excretion of nitroge- nous wastes, and acid-base regulation.1 The gills are the primary site of oxygen exchange in fish and are in intimate contact with the aquatic environment. In most cases, the separation between the water and the tissues of the fish is only a few cell layers thick. Gills are a common target for assault by infectious and noninfectious disease processes.2 Nonlethal diagnostic biopsy of the gills can identify pathologic changes, provide samples for bacterial culture/identification/sensitivity testing, aid in fungal element identification, provide samples for viral testing, and provide parasitic organisms for identification.3–6 This diagnostic test is so important that it should be included as part of every diagnostic workup performed on a fish. -

Gill Morphometrics of the Thresher Sharks (Genus Alopias): Correlation of Gill Dimensions with Aerobic Demand and Environmental Oxygen

JOURNAL OF MORPHOLOGY :1–12 (2015) Gill Morphometrics of the Thresher Sharks (Genus Alopias): Correlation of Gill Dimensions with Aerobic Demand and Environmental Oxygen Thomas P. Wootton,1 Chugey A. Sepulveda,2 and Nicholas C. Wegner1,3* 1Center for Marine Biotechnology and Biomedicine, Marine Biology Research Division, Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA 92093 2Pfleger Institute of Environmental Research, Oceanside, CA 92054 3Fisheries Resource Division, Southwest Fisheries Science Center, NOAA Fisheries, La Jolla, CA 92037 ABSTRACT Gill morphometrics of the three thresher related species that inhabit similar environments shark species (genus Alopias) were determined to or have comparable metabolic requirements. As examine how metabolism and habitat correlate with such, in reviews of gill morphology (e.g., Gray, respiratory specialization for increased gas exchange. 1954; Hughes, 1984a; Wegner, 2011), fishes are Thresher sharks have large gill surface areas, short often categorized into morphological ecotypes water–blood barrier distances, and thin lamellae. Their large gill areas are derived from long total filament based on the respiratory dimensions of the gills, lengths and large lamellae, a morphometric configura- namely gill surface area and the thickness of the tion documented for other active elasmobranchs (i.e., gill epithelium (the water–blood barrier distance), lamnid sharks, Lamnidae) that augments respiratory which both reflect a species’ capacity for oxygen surface area while -

Mucosal Barrier Functions of Fish Under Changing Environmental Conditions

fishes Review Mucosal Barrier Functions of Fish under Changing Environmental Conditions Nikko Alvin R. Cabillon 1,* and Carlo C. Lazado 2 1 Scottish Association for Marine Science—University of Highlands and Islands, Oban PA37 1QA, UK 2 Nofima, Norwegian Institute of Food, Fisheries and Aquaculture Research, 1430 Ås, Norway; carlo.lazado@nofima.no * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +63-907-420-5685 Received: 27 November 2018; Accepted: 7 January 2019; Published: 10 January 2019 Abstract: The skin, gills, and gut are the most extensively studied mucosal organs in fish. These mucosal structures provide the intimate interface between the internal and external milieus and serve as the indispensable first line of defense. They have highly diverse physiological functions. Their role in defense can be highlighted in three shared similarities: their microanatomical structures that serve as the physical barrier and hold the immune cells and the effector molecules; the mucus layer, also a physical barrier, contains an array of potent bioactive molecules; and the resident microbiota. Mucosal surfaces are responsive and plastic to the different changes in the aquatic environment. The direct interaction of the mucosa with the environment offers some important information on both the physiological status of the host and the conditions of the aquatic environment. Increasing attention has been directed to these features in the last year, particularly on how to improve the overall health of the fish through manipulation of mucosal functions and on how the changes in the mucosa, in response to varying environmental factors, can be harnessed to improve husbandry. In this short review, we highlight the current knowledge on how mucosal surfaces respond to various environmental factors relevant to aquaculture and how they may be exploited in fostering sustainable fish farming practices, especially in controlled aquaculture environments. -

Evolution of the Nitric Oxide Synthase Family in Vertebrates and Novel

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.14.448362; this version posted June 14, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Evolution of the nitric oxide synthase family in vertebrates 2 and novel insights in gill development 3 4 Giovanni Annona1, Iori Sato2, Juan Pascual-Anaya3,†, Ingo Braasch4, Randal Voss5, 5 Jan Stundl6,7,8, Vladimir Soukup6, Shigeru Kuratani2,3, 6 John H. Postlethwait9, Salvatore D’Aniello1,* 7 8 1 Biology and Evolution of Marine Organisms, Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn, 80121, 9 Napoli, Italy 10 2 Laboratory for Evolutionary Morphology, RIKEN Center for Biosystems Dynamics 11 Research (BDR), Kobe, 650-0047, Japan 12 3 Evolutionary Morphology Laboratory, RIKEN Cluster for Pioneering Research (CPR), 2-2- 13 3 Minatojima-minami, Chuo-ku, Kobe, Hyogo, 650-0047, Japan 14 4 Department of Integrative Biology and Program in Ecology, Evolution & Behavior (EEB), 15 Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA 16 5 Department of Neuroscience, Spinal Cord and Brain Injury Research Center, and 17 Ambystoma Genetic Stock Center, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky, USA 18 6 Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, Charles University in Prague, Prague, Czech 19 Republic 20 7 Division of Biology and Biological Engineering, California Institute of Technology, 21 Pasadena, CA, USA 22 8 South Bohemian Research Center of Aquaculture and Biodiversity of Hydrocenoses, 23 Faculty of Fisheries and Protection of Waters, University of South Bohemia in Ceske 24 Budejovice, Vodnany, Czech Republic 25 9 Institute of Neuroscience, University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97403, USA 26 † Present address: Department of Animal Biology, Faculty of Sciences, University of 27 Málaga; and Andalusian Centre for Nanomedicine and Biotechnology (BIONAND), 28 Málaga, Spain 29 30 * Correspondence: [email protected] 31 32 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.14.448362; this version posted June 14, 2021. -

Culturing and Environmental DNA Sequencing Uncover Hidden Kinetoplastid Biodiversity and a Major Marine Clade Within Ancestrally Freshwater Neobodo Designis

International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology (2005), 55, 2605–2621 DOI 10.1099/ijs.0.63606-0 Culturing and environmental DNA sequencing uncover hidden kinetoplastid biodiversity and a major marine clade within ancestrally freshwater Neobodo designis Sophie von der Heyden3 and Thomas Cavalier-Smith Correspondence Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PS, UK Thomas Cavalier-Smith [email protected] Bodonid flagellates (class Kinetoplastea) are abundant, free-living protozoa in freshwater, soil and marine habitats, with undersampled global biodiversity. To investigate overall bodonid diversity, kinetoplastid-specific PCR primers were used to amplify and sequence 18S rRNA genes from DNA extracted from 16 diverse environmental samples; of 39 different kinetoplastid sequences, 35 belong to the subclass Metakinetoplastina, where most group with the genus Neobodo or the species Bodo saltans, whilst four group with the subclass Prokinetoplastina (Ichthyobodo). To study divergence between freshwater and marine members of the genus Neobodo, 26 new Neobodo designis strains were cultured and their 18S rRNA genes were sequenced. It is shown that the morphospecies N. designis is a remarkably ancient species complex with a major marine clade nested among older freshwater clades, suggesting that these lineages were constrained physiologically from moving between these environments for most of their long history. Other major bodonid clades show less-deep separation between marine and freshwater strains, but have extensive genetic diversity within all lineages and an apparently biogeographically distinct distribution of B. saltans subclades. Clade-specific 18S rRNA gene primers were used for two N. designis subclades to test their global distribution and genetic diversity. -

The Microbial Food Web of the Coastal Southern Baltic Sea As Influenced by Wind-Induced Sediment Resuspension

THE MICROBIAL FOOD WEB OF THE COASTAL SOUTHERN BALTIC SEA AS INFLUENCED BY WIND-INDUCED SEDIMENT RESUSPENSION I n a u g u r a l - D i s s e r t a t i o n zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität zu Köln vorgelegt von TOBIAS GARSTECKI aus Magdeburg Köln, 2001 Berichterstatter: Prof. Dr. STEPHEN A. WICKHAM Prof. Dr. HARTMUT ARNDT Tag der letzten mündlichen Prüfung: 29.06.2001 Inhaltsverzeichnis Angabe von verwendeten Fremddaten .............................................. 5 Abkürzungsverzeichnis ..................................................................... 6 1. Einleitung ........................................................................................................ 7 1.1. Begründung der Fragestellung ......................................................... 7 1.2. Herangehensweise ..................................................................... 11 2. A comparison of benthic and planktonic heterotrophic protistan community structure in shallow inlets of the Southern Baltic Sea ........… 13 2.1. Summary ................... ........................................................................ 13 2.2. Introduction ................................................................................. 14 2.3. Materials and Methods ..................................................................... 15 2.3.1. Study sites ..................................................................... 15 2.3.2. Sampling design ........................................................ -

Heme Pathway Evolution in Kinetoplastid Protists Ugo Cenci1,2, Daniel Moog1,2, Bruce A

Cenci et al. BMC Evolutionary Biology (2016) 16:109 DOI 10.1186/s12862-016-0664-6 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Heme pathway evolution in kinetoplastid protists Ugo Cenci1,2, Daniel Moog1,2, Bruce A. Curtis1,2, Goro Tanifuji3, Laura Eme1,2, Julius Lukeš4,5 and John M. Archibald1,2,5* Abstract Background: Kinetoplastea is a diverse protist lineage composed of several of the most successful parasites on Earth, organisms whose metabolisms have coevolved with those of the organisms they infect. Parasitic kinetoplastids have emerged from free-living, non-pathogenic ancestors on multiple occasions during the evolutionary history of the group. Interestingly, in both parasitic and free-living kinetoplastids, the heme pathway—a core metabolic pathway in a wide range of organisms—is incomplete or entirely absent. Indeed, Kinetoplastea investigated thus far seem to bypass the need for heme biosynthesis by acquiring heme or intermediate metabolites directly from their environment. Results: Here we report the existence of a near-complete heme biosynthetic pathway in Perkinsela spp., kinetoplastids that live as obligate endosymbionts inside amoebozoans belonging to the genus Paramoeba/Neoparamoeba.Wealso use phylogenetic analysis to infer the evolution of the heme pathway in Kinetoplastea. Conclusion: We show that Perkinsela spp. is a deep-branching kinetoplastid lineage, and that lateral gene transfer has played a role in the evolution of heme biosynthesis in Perkinsela spp. and other Kinetoplastea. We also discuss the significance of the presence of seven of eight heme pathway genes in the Perkinsela genome as it relates to its endosymbiotic relationship with Paramoeba. Keywords: Heme, Kinetoplastea, Paramoeba pemaquidensis, Perkinsela, Evolution, Endosymbiosis, Prokinetoplastina, Lateral gene transfer Background are poorly understood and the evolutionary relationship Kinetoplastea is a diverse group of unicellular flagellated amongst bodonids is still debated [8, 10, 12]. -

(2011) Quantitative Analysis of the Fine Structure of the Fish Gill: Environmental Response and Relation to Welfare

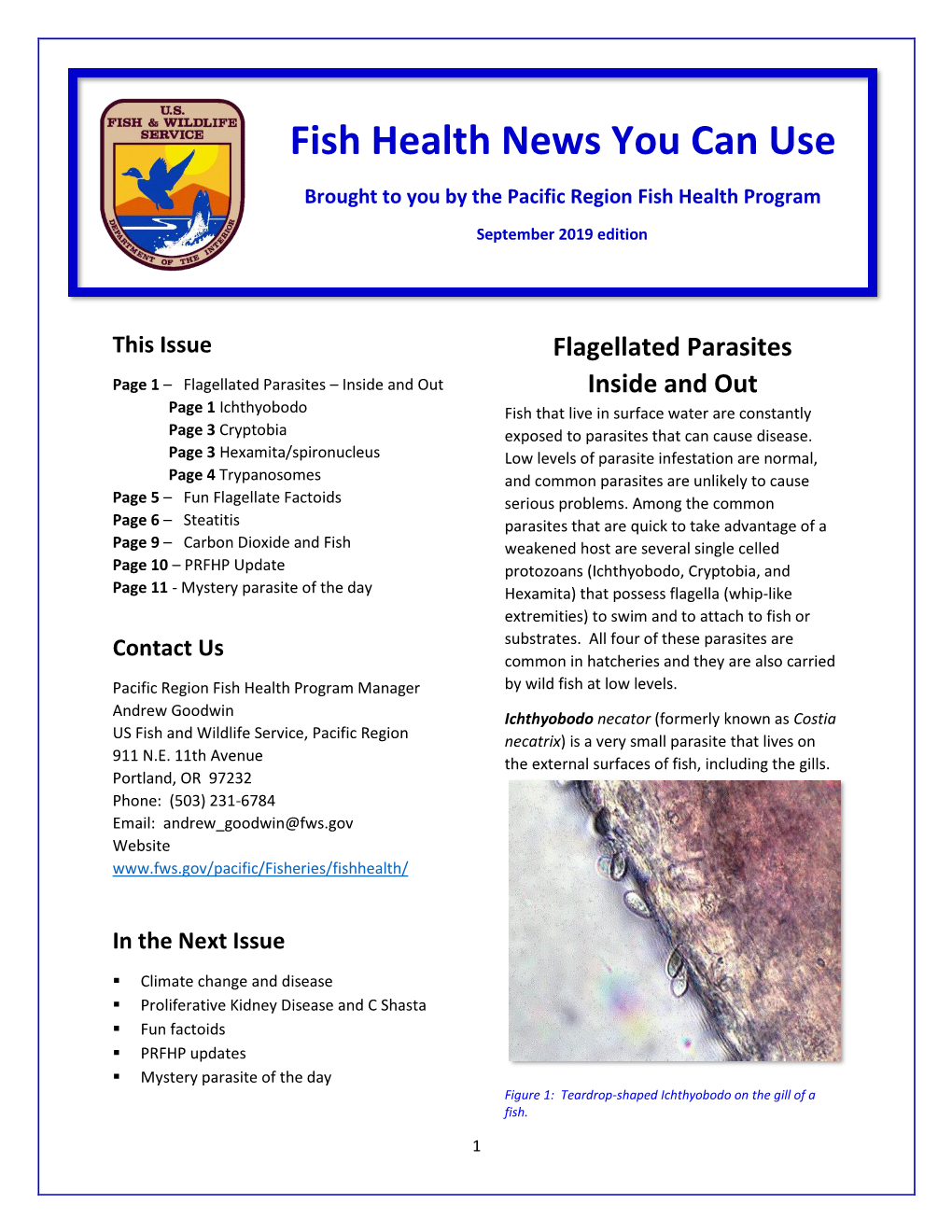

Jenjan, Hussein B.B. (2011) Quantitative analysis of the fine structure of the fish gill: environmental response and relation to welfare. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/3033/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE FINE STRUCTURE OF THE FISH GILL: ENVIRONMENTAL RESPONSE AND RELATION TO WELFARE. Fish Feeding by Hawaa Jenjan Hussein B.B. Jenjan Thesis submitted for degress of Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Biodiversity Animal Health and Comparative Medicine College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences University of Glasgow September, 2011 Abstract • Methods were developed to quantify variation in gill size and microstructure and applied to three fish species: brown trout, Arctic charr and common carp. Measurements of arch length, number and length of gill rakers, number and length of gill filaments and number, length and spacing of the lamellae were taken for each gill arch and combined by principal component analyses to give length-independent scores of gill size. Levels of fluctuating asymmetry in gill arch length were also examined. -

1 1 2 3 Hierarchical Stem Cell Topography Splits Growth and Homeostatic Functions in the 4 Fish Gill. 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 1

1 2 3 4 Hierarchical Stem Cell Topography Splits Growth and Homeostatic Functions in the 5 Fish Gill. 6 7 Julian Stolper1,2, Elizabeth Ambrosio1,6, Diana-P Danciu3, Lorena Buono4, David A. Elliot2, Kiyoshi 8 Naruse5, Juan-Ramon Martinez Morales4, Anna Marciniak Czochra3 & Lazaro Centanin1,#. 9 10 1Centre for Organismal Studies, Heidelberg University, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany 11 2Murdoch Children’s Research Institute, Royal Children’s Hospital, Parkville, VIC, 3052, Australia 12 3Institute of Applied Mathematics, Interdisciplinary Center for Scientific Computing (IWR) and 13 BIOQUANT Center, Heidelberg University, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany 14 4Centro Andaluz de Biología del Desarrollo, Universidad Pablo de Olavide, Carretera de Utrera km 15 1, 41013 Seville, Spain. 16 5Laboratory of Bioresources, National Institute for Basic Biology, National Institutes of Natural 17 Sciences, Okazaki, Aichi 444-8585, Japan 18 6Current address: The Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Stem Cell Research (DanStem), 19 University of Copenhagen, 2200 Copenhagen N, Denmark 20 #Author for correspondence: [email protected] 21 1 22 Abstract 23 While lower vertebrates contain adult stem cells (aSCs) that maintain homeostasis and drive un- 24 exhaustive organismal growth, mammalian aSCs display mainly the homeostatic function. Here we 25 use lineage analysis in the fish gill to address aSCs and report separate stem cell populations for 26 homeostasis and growth. These aSCs are fate-restricted during the entire post-embryonic life and 27 even during re-generation paradigms. We use chimeric animals to demonstrate that p53 mediates 28 growth coordination among fate-restricted aSCs, suggesting a hierarchical organisation among 29 lineages in composite organs like the fish gill. -

Arterio-Venous Branchial Blood Flow in the Atlantic Cod Gadus Morhua

J. exp. Biol. 165, 73-84 (1992) 73 Printed in Great Britain © The Company of Biologists Limited 1992 ARTERIO-VENOUS BRANCHIAL BLOOD FLOW IN THE ATLANTIC COD GADUS MORHUA BY LENA SUNDIN AND STEFAN NILSSON Comparative Neuroscience Unit, Department of Zoophysiology, University of Gdteborg, PO Box 25059, S-400 31 Gdteborg, Sweden Accepted 18 November 1991 Summary We have estimated the branchial venous blood flow in the Atlantic cod by direct single-crystal Doppler blood flow measurements in vivo. In the undisturbed animal, this flow amounts to 1.7 ml min~: kg~', which corresponds to about 8 % of the cardiac output. Studies of both an isolated perfused gill apparatus in situ and simultaneous measurements of cardiac output and branchial venous flow in vivo were made to assess the effects of some putative vasoregulatory substances. Adrenaline dilates the arterio-arterial pathway and constricts the arterio-venous pathway, thus decreasing branchial venous drainage. 5-Hydroxytryptamine (5- HT), in contrast, produced marked vasoconstriction in the arterio-arterial pathway of the branchial vasculature, increasing the branchial venous blood flow. Cholecystokinin-8 (CCK-8) and caerulein produced similar cardiovascular effects, with marked constriction of both arterio-arterial and arterio-venous pathways. The study demonstrates the ability of the vascular system of the gills to regulate the distribution of branchial blood flow, and summarizes the vasomotor effects of some substances with possible vasomotor function in the cod gills. Introduction Blood entering the branchial circulation of the cod through the afferent branchial arteries may leave the gills via two different routes after passing the lamellae: (1) via the efferent filamental arteries, which run to the suprabranchial arteries distributing blood to the systemic circulation via the dorsal aorta (arterio- arterial pathway), or (2) via the branchial veins into the inferior jugular veins ventrally and the anterior cardinal veins dorsally (arterio-venous pathway). -

AQPX-Cluster Aquaporins and Aquaglyceroporins Are

ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-021-02472-9 OPEN AQPX-cluster aquaporins and aquaglyceroporins are asymmetrically distributed in trypanosomes ✉ ✉ Fiorella Carla Tesan 1,2, Ramiro Lorenzo 3, Karina Alleva 1,2,4 & Ana Romina Fox 3,4 Major Intrinsic Proteins (MIPs) are membrane channels that permeate water and other small solutes. Some trypanosomatid MIPs mediate the uptake of antiparasitic compounds, placing them as potential drug targets. However, a thorough study of the diversity of these channels is still missing. Here we place trypanosomatid channels in the sequence-function space of the large MIP superfamily through a sequence similarity network. This analysis exposes that trypanosomatid aquaporins integrate a distant cluster from the currently defined MIP 1234567890():,; families, here named aquaporin X (AQPX). Our phylogenetic analyses reveal that trypano- somatid MIPs distribute exclusively between aquaglyceroporin (GLP) and AQPX, being the AQPX family expanded in the Metakinetoplastina common ancestor before the origin of the parasitic order Trypanosomatida. Synteny analysis shows how African trypanosomes spe- cifically lost AQPXs, whereas American trypanosomes specifically lost GLPs. AQPXs diverge from already described MIPs on crucial residues. Together, our results expose the diversity of trypanosomatid MIPs and will aid further functional, structural, and physiological research needed to face the potentiality of the AQPXs as gateways for trypanocidal drugs. 1 Universidad de Buenos Aires, Facultad de Farmacia y Bioquímica, Departamento de Fisicomatemática, Cátedra de Física, Buenos Aires, Argentina. 2 CONICET-Universidad de Buenos Aires, Instituto de Química y Fisicoquímica Biológicas (IQUIFIB), Buenos Aires, Argentina. 3 Laboratorio de Farmacología, Centro de Investigación Veterinaria de Tandil (CIVETAN), (CONICET-CICPBA-UNCPBA) Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias, Universidad Nacional del Centro ✉ de la Provincia de Buenos Aires, Tandil, Argentina.