Audubon Florida Naturalist Magazine Winter 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Everglades Biographies Everglades Biographies

Everglades Digital Library Guide to Collection Everglades Timeline Everglades Biographies Everglades Biographies Research Help Everglades Librarian Ordering Reproductions Copyright Credits Home Search the Expanded Collection Browse the Expanded Collection Bowman F. Ashe James Edmundson Ingraham Ivar Axelson James Franklin Jaudon Mary McDougal Axelson May Mann Jennings Access the Original Richard J. Bolles Claude Carson Matlack Collection at Chief Billy Bowlegs Daniel A. McDougal Guy Bradley Minnie Moore-Willson Napoleon Bonaparte Broward Frederick S. Morse James Milton Carson Mary Barr Munroe Ernest F. Coe Ralph Middleton Munroe Barron G. Collier Ruth Bryan Owen Marjory Stoneman Douglas John Kunkel Small David Fairchild Frank Stranahan Ion Farris Ivy Julia Cromartie Stranahan http://everglades.fiu.edu/reclaim/bios/index.htm[10/1/2014 2:16:58 PM] Everglades Digital Library Henry Flagler James Mallory Willson Duncan Upshaw Fletcher William Sherman Jennings John Clayton Gifford Home | About Us | Browse | Ask an Everglades Librarian | FIU Libraries This site is designed and maintained by the Digital Collections Center - [email protected] Everglades Information Network & Digital Library at Florida International University Libraries Copyright © Florida International University Libraries. All rights reserved. http://everglades.fiu.edu/reclaim/bios/index.htm[10/1/2014 2:16:58 PM] Everglades Digital Library Guide to Collection Everglades Timeline Everglades Biographies Everglades Biographies Bowman Foster Ashe Research Help Bowman Foster Ashe, a native of Scottsdale, Pennsylvania, came to Miami in Everglades Librarian 1926 to be involved with the foundation of the University of Miami. Dr. Ashe graduated from the University of Pittsburgh and held honorary degrees from the Ordering Reproductions University of Pittsburgh, Stetson University, Florida Southern College and Mount Union College. -

Wilderness on the Edge: a History of Everglades National Park

Wilderness on the Edge: A History of Everglades National Park Robert W Blythe Chicago, Illinois 2017 Prepared under the National Park Service/Organization of American Historians cooperative agreement Table of Contents List of Figures iii Preface xi Acknowledgements xiii Abbreviations and Acronyms Used in Footnotes xv Chapter 1: The Everglades to the 1920s 1 Chapter 2: Early Conservation Efforts in the Everglades 40 Chapter 3: The Movement for a National Park in the Everglades 62 Chapter 4: The Long and Winding Road to Park Establishment 92 Chapter 5: First a Wildlife Refuge, Then a National Park 131 Chapter 6: Land Acquisition 150 Chapter 7: Developing the Park 176 Chapter 8: The Water Needs of a Wetland Park: From Establishment (1947) to Congress’s Water Guarantee (1970) 213 Chapter 9: Water Issues, 1970 to 1992: The Rise of Environmentalism and the Path to the Restudy of the C&SF Project 237 Chapter 10: Wilderness Values and Wilderness Designations 270 Chapter 11: Park Science 288 Chapter 12: Wildlife, Native Plants, and Endangered Species 309 Chapter 13: Marine Fisheries, Fisheries Management, and Florida Bay 353 Chapter 14: Control of Invasive Species and Native Pests 373 Chapter 15: Wildland Fire 398 Chapter 16: Hurricanes and Storms 416 Chapter 17: Archeological and Historic Resources 430 Chapter 18: Museum Collection and Library 449 Chapter 19: Relationships with Cultural Communities 466 Chapter 20: Interpretive and Educational Programs 492 Chapter 21: Resource and Visitor Protection 526 Chapter 22: Relationships with the Military -

Keepers of Fort Lauderdale's House of Refuge

KEEPERS OF FORT LAUDERDALE’S HOUSE OF REFUGE The Men Who Served at Life Saving Station No. 4 from 1876 to 1926 By Ruth Landini In 1876, the U.S. Government extended the welcome arm of the U.S. Life-Saving Service down the long, deserted southeast coast of Florida. Five life saving stations, called Houses of Refuge, were built approximately 25 miles apart. Construction of House Number Four in Fort Lauderdale was completed on April 24, 1876, and was situated near what is today the Bonnet House Museum and Garden. Its location was on the main dune of the barrier island that is approximately four miles north of the New River Inlet. Archaeological fi nds from that time have been discovered in the area and an old wellhead still exists at this location. House of Refuge. The houses were the homes of the keepers and their Courtesy of Mrs. Robert families, who were also required to go along the beach, Powell. in both directions, in search of castaways immediately after a storm.1 Keepers were not expected, nor were they equipped, to effect actual lifesaving, but merely were required to provide food, water and a dry bed for visitors and shipwrecked sailors who were lucky enough to have gained shore. Prior to 1876, when the entire coast of Florida was windswept and infested with mosquitoes, fresh water was diffi cult to obtain. Most of the small settlements were on the mainland, and shipwrecked men had a fearful time in what was years later considered a “Tropical Paradise.” There was a desperate need for rescue facilities. -

Florida's Paradox of Progress: an Examination of the Origins, Construction, and Impact of the Tamiami Trail

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2012 Florida's Paradox Of Progress: An Examination Of The Origins, Construction, And Impact Of The Tamiami Trail Mark Schellhammer University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Schellhammer, Mark, "Florida's Paradox Of Progress: An Examination Of The Origins, Construction, And Impact Of The Tamiami Trail" (2012). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 2418. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/2418 FLORIDA’S PARADOX OF PROGRESS: AN EXAMINATION OF THE ORIGINS, CONSTRUCTION, AND IMPACT OF THE TAMIAMI TRAIL by MARK DONALD SCHELLHAMMER II B.S. Florida State University, 2007 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2012 © 2012 by Mark Schellhammer II ii ABSTRACT This study illustrates the impact of the Tamiami Trail on the people and environment of South Florida through an examination of the road’s origins, construction and implementation. By exploring the motives behind building the highway, the subsequent assimilation of indigenous societies, the drastic population growth that occurred as a result of a propagated “Florida Dream”, and the environmental decline of the surrounding Everglades, this analysis reveals that the Tamiami Trail is viewed today through a much different context than that of the road’s builders and promoters in the early twentieth century. -

Park Stories

National Park Service National Parks of South Florida U.S. Department of the Interior Biscayne, Dry Tortugas and Everglades National Parks Big Cypress National Preserve Park Stories Current Stories and Events for the National Parks in South Florida, 2005 Hurricanes: Reclaiming Nature in South Florida South Florida’s National Parks National Parks... ... protect coral reefs, fragile estuaries, When faced with the swirling image of a hurricane, you might might obliterate what remains of this part of the Bay’s color- sub-tropical forests and some of the larg- imagine yourself hunkering down in a concrete bunker or ful history. Although hurricanes may eventually be the undo- est natural areas east of the Mississippi River, and preserve a rich human history. high-tailing it out of town. The thought of crouching behind ing of Stiltsville, they help preserve its reason for being. Hur- a sand dune, clinging to a mangrove tree or treading water ricanes temporarily restore the pulse of fresh water needed ... are home to a variety of temperate and next to a coral reef to ride out the storm probably sends shiv- to maintain healthy seagrass beds which, in turn, support rich tropical plants and animals that co-mingle ers down your spine (and, is not recommended!). But during fi sheries. nowhere else within the United States. a hurricane our human-made structures weather, by far, the worst of the storm while these “fragile” natural features are Shifting Sands and Mud at the Dry Tortugas ... provide a wide range of recreational op- designed to temper nature’s fury. Seventy miles from Key West, the islands of the Dry Tortugas portunities for visitors and residents. -

South Florida National Park Sites

National Park Service National Parks and Preserves U.S. Department of the Interior of South Florida Ranger Station Interpretive Trail Bear Island Alligator Alley (Toll Road) Campground Primitive Camping Rest Area, F 75 75 foot access only l o ri Gasoline Lodging and Meals da to Naples N a No Access to/from t i o Alligator Alley n Restrooms Park Area Boundary a 839 l S c Picnic Area e Public Boat Ramp n i SR 29 c T r Marina a il to Naples 837 Big Cypress 837 National Preserve 1 Birdon Road Turner River Road River Turner 41 841 Big Cypress Visitor Center EVERGLADES 41 821 CITY Gulf Coast Visitor Center Tree Snail Hammock Nature Trail Tamiami Trail Krome Ave. MIAMI 41 Loop Road Shark Valley Visitor Center Florida's Turnpike Florida's 1 SW 168th St. Chekika Everglades Biscayne SR 997 National Park National Park HOMESTEAD Boca Chita Key Exit 6 Dante Fascell Pinelands Visitor Center Pa-hay-okee Coe Gulf of Mexico Overlook N. Canal Dr. Visitor (SW 328 St.) Center Elliott Key 9336 Long Pine Key (Palm Dr.) Mahogany 1 Hammock Royal Palm Visitor Center Anhinga Trail Gumbo Limbo Trail West Lake Atlantic Ocean Flamingo Visitor Center Key Largo Fort Jefferson Florida Bay 1 North Dry Tortugas 0 5 10 Kilometers National Park 05 10 Miles 0 2 4 70 miles west of Key West, Note: This map is not a substitute for an Miles by plane or boat only. up-to-date nautical chart or hiking map. Big Cypress, Biscayne, Dry Tortugas, and Everglades Phone Numbers Portions of Biscayne and 95 826 Everglades National Parks National Park Service Website: http://www.nps.gov 95 Florida Turnpike Florida Tamiami Trail Miami Important Phone Numbers 41 41 Shark Valley 826 Visitor Center 1 Below is a list of phone numbers you may need to help plan your trip to the 874 south Florida national parks and preserves. -

GUY BRADLEY MEMORIAL Dan Maddalino

GUY BRADLEY MEMORIAL Dan Maddalino Florida dedication covers extend beyond airports and post offices. With the example shown, we are presented a cover with the corner card for the Tropical Audubon Society, Inc., Miami, Florida. The hand stamp cancellation is a double circle with Everglades National Park Ranger Station, Flamingo, and Homestead, Florida within the circles. The date March 30, 1976 completes the cancellation information. The stamps represent The Everglades National Park, Wildlife Conservation, and John J. Audubon. The signatures are of distinguished officers from various branches of the Audubon Society, as well as the National Park Superintendent. The occasion? The dedication of the Guy Bradley Memorial plaque at the Flamingo Visitors Center in Everglades National Park (ENP). Who was Guy Bradley and why is he memorialized in the park? Guy Morrell Bradley (April 25, 1870 – July 8, 1905) was a game warden and deputy sheriff for Monroe County, Florida. Born in Chicago, Illinois, he relocated to Florida with his family when he was young. As a boy, he served as guide to visiting fishermen and plume hunters, although he later denounced poaching. Bradley was hired by the American Ornithologists’ Union, at the request of the Florida Audubon Society, to become one of this country's first game wardens. His primary responsibility was protecting the area's plume birds from hunters. He patrolled the area stretching from Florida's west coast, through the Everglades, to Key West. He was the only game warden enforcing the ban on bird hunting. Bradley was shot and killed in the line of duty, after confronting a man and his two sons who were hunting plume birds. -

Kite Everglade

EVERGLADE KITE THE AUDUBON SOCIETY OF THE EVERGLADES (serving Palm Beach County, Florida) Volume 45, No. 5 February 2005 >>> CALENDAR <<< TUESDAY FEBRUARY 1st, PROGRAM SAT. Feb. 5, 9:00 a.m. John Prince Park, Nature Walk on Custard Apple Nature Trail. Meet oppo- The Story of LILA site campground entrance. by Dale Gawlik, Ph.D. Leader: Bruce Offord. Who is LILA? LILA means Loxahatchee Impoundment TUES. Feb. 8, 8 a.m. Delray Oaks Natural Area, Landscape Assessment and Dr. Gawlik is our special 2021 S.W. 29th St. & Congress Ave. (south of Linton), Delray Beach. guest speaker to tell us about this project, which stud- Leader: Barbara Liberman. ies water levels and vegetation relative to wading birds and other wildlife. Each February our speaker enlight- THURS. Feb. 10, 6:00 p.m. Art preview and auc- ens us about some aspect of the Arthur R. Marshall tion. See details on page 3. Loxahatchee National Wildlife Refuge as part of the Ev- SAT. Feb. 12, 8 a.m. – 4 p.m. Everglades Day, erglades system. It is like a prelude to our "Everglades Loxahatchee NWR. See details on page 3. Day!" SAT. Feb. 19, 8:00 a.m. Belle Glade Camp- Dr. Gawllik calls himself an avian ecologist and wet- ground. Meet at 7:00 a.m at Target to carpool. Southern Blvd at St. Rd. 7/441, park on west side lands specialist. He received his B.S. at U. of Wiscon- next to Garden Center. Bring lunch. Leader: sin Stevens Point, M.S. from Winthrop University, Rock Chuck Weber. -

BIG SIT! Report the SAS Team, Seminole Sitters, Competed in the 19Th Annual Big SIT! on Sunday October 12 at Lake Jesup Park

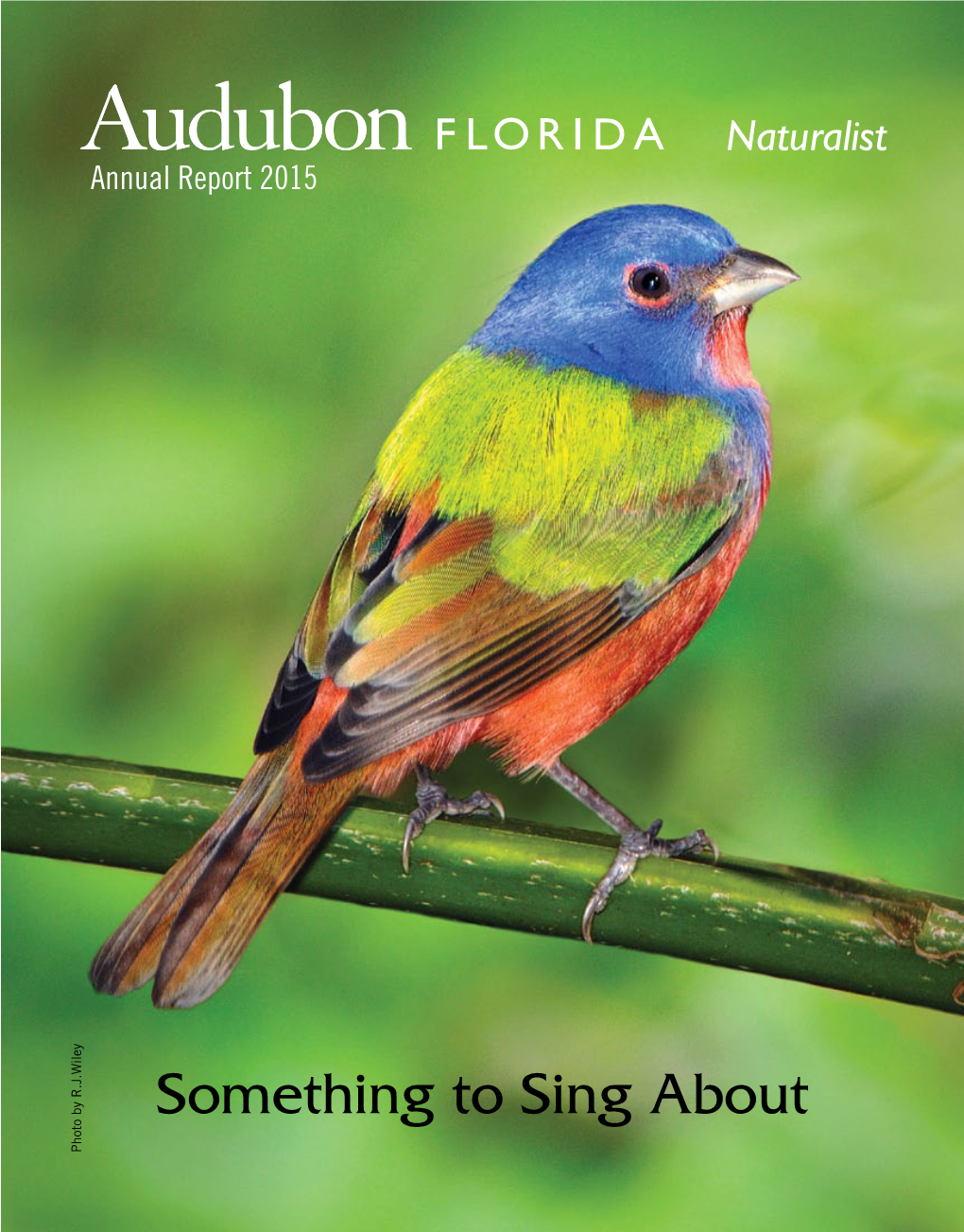

The mission of the Seminole Audubon Society is to promote awareness and protection of the plants and animals in the St. Johns River basin in order to sustain the beneficial coexistence of nature and humans. November - December 2014 A Publication of Seminole Audubon Society BIG SIT! Report The SAS team, Seminole Sitters, competed in the 19th annual Big SIT! on Sunday October 12 at Lake Jesup Park. The Big SIT! is a species count described by its sponsor, BirdWatcher’s Digest, as “Birding’s Most Sedentary Event.” Unlike most bird counts that involve traveling to various spots along a route or within an area, the Big SIT! is done from a 17’ circle. The 2014 Big Sit! consisted of 184 competing circles in 50 states and countries. Our team included sixteen birders this year. Many arrived before the sun, but not before the boaters. The location where we have erected the canopy in previous years was under water forcing us to adjust our location slightly. New species for our Big SIT! count included least bittern and purple gallinules. We were happy nearly as many species. to see American bitterns, king rails, our friendly limpkins, and painted buntings. Although many We had stiff competition this year with nine count of our regularly-seen species were absent this year, circles competing for the highest count in Florida. our final count was 53 species. We extend our The Celery Fields Forever team of Sarasota won the special thanks once again to Paul Hueber, without whose expertise we would not have tallied See BIG SIT! on page 13 The printing and mailing of this newsletter is made possible in part by the generous donations of Bob and Inez Parsell and ACE Hardware stores in Sanford, Longwood, Casselberry, and Oviedo. -

Everglades Everglades National Park

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Everglades Everglades National Park Flamingo Canoe Trails Caution: Tides and winds can significantly affect your canoe trip. Do not over- estimate your abilities. 1 Nine Mile Pond more detailed trail map is available. Motors are Venture inland through the mangroves on this 5.2 mile loop prohibited from the trailhead to Lard Can. A trail connecting the Buttonwood Canal, Coot This scenic trail passes through shallow grassy wilderness permit is required for overnight Bay, Mud Lake, and Bear Lake. Birding can be camping. good at Mud Lake. Accessible from the Bear marsh with scattered mangrove islands. Watch for alligators, wading birds, and an occasional Lake Trailhead into the Buttonwood Canal or 4 Florida Bay Coot Bay Pond. Motors are prohibited on Mud endangered snail kite. The trail is marked with Distance varies numbered white poles. A more detailed trail Lake and Bear Lake. Check the Visitor Center Opportunities for fun abound! Watch mullet for current status of this trail. map is available. Trail may be impassable due jump and birds feed (particularly at Snake to low water levels near the end of the dry sea- Bight), do some fishing, or just enjoy the scenic 7 West Lake son. Motors prohibited. bay. Explore Bradley Key (during daylight 7.7 miles one way to Alligator Creek 2 Noble Hammock hours only), the only nearby key open to land- Paddle through a series of large open lakes 2 mile loop ing. The open waters of Florida Bay are rela- connected by narrow creeks lined with man- The sharp turns and narrow passageways tively mosquito-free, even in summer. -

The Owl and the Monitor: Nature Versus Neighborhood in the Development of Southwest Florida Nicholas Foreman, Oregon State University

The Owl and the Monitor: Nature Versus Neighborhood in the Development of Southwest Florida Nicholas Foreman, Oregon State University On the southwestern coast of Florida, pinched between suburban homes and a shrinking tangle of mangrove islands near the mouth of the Caloosahatchee River, two unlikely rivals act out a curious endgame of twentieth-century consumerism. Here, one of Florida’s last surviving populations of burrowing owls is threatened by the Nile monitor, a four-foot lizard brought to the Gulf Coast by the exotic pet trade in the 1980s. In the decades since its introduction, the monitor’s ability to thrive in this coastal setting with hundreds of manmade canals has enabled it to proliferate and displace native fauna like the owl, drawing concern from ecologists and concerned citizens alike. State agencies and local newspapers have published dozens of short articles and impact studies that call our attention to the problem of exotic pests in Florida’s fragile ecosystems, and in Cape Coral itself, the monitor has become something of a supervillain, evading wildlife officers charged with its removal and menacing residents and their pets from the warm concrete of the city’s many seawalls. But these two animals’ inverse relationship reflects more than the danger of invasive species within the borderlands of the Anthropocene. The story of the owl and the monitor is also a parable for the ways in which certain conceptions of nature and patterns of consumption created by post-WWII housing speculation have continued to define humans’ impact on Florida’s environment and turned the Sunshine State into a symbol of Americans’ most ambitious—and destructive—tendencies. -

Appendix A. Brief History of Audubon's Lake Okeechobee Program at the End of the 19 Century, the United States Was Recognizing

Appendix A. Brief history of Audubon's Lake Okeechobee program At the end of the 19 th Century, the United States was recognizing the devastating impacts of unregulated harvest of our wildlife resources, particularly birds. Frank Chapman's 1903 book, "Bird-life: a guide to the study of our common birds” noted, "…the Snowy Heron and White Egret, are adorned during the nesting season with the beautiful "aigrette" plumes which are apparently so necessary a part of woman's headgear that they will go out of fashion only when the birds go out of existence…Still, we have no law to prevent it." Of the Passenger Pigeon he stated, "Less than fifty years ago it was exceedingly abundant, but....the birds were pursued so relentlessly that they have been practically exterminated." Throughout his book, Chapman makes the case that birds are usually beneficial to humans and should be protected. Chapman and other leading ornithologists of the day were very important in early state Audubon Societies, and the Bird Protection Committee of the American Ornithological Union (AOU), that were inducing legislatures around the country to pass the "AOU Model Law" protecting birds. William Dutcher, chair of the committee on bird protection of the American Ornithological Union, and soon-to-be first president of the National Association of Audubon Societies, helped urge Florida to pass the model law in 1901. Florida itself provided no wardens to enforce the law (Orr 1992), thus it was Audubon who paid the salaries of the first wardens in Florida (Graham 1990). Four wardens were originally hired, two being subsequently slain in the line of duty (Howell 1932, McIver 2003).