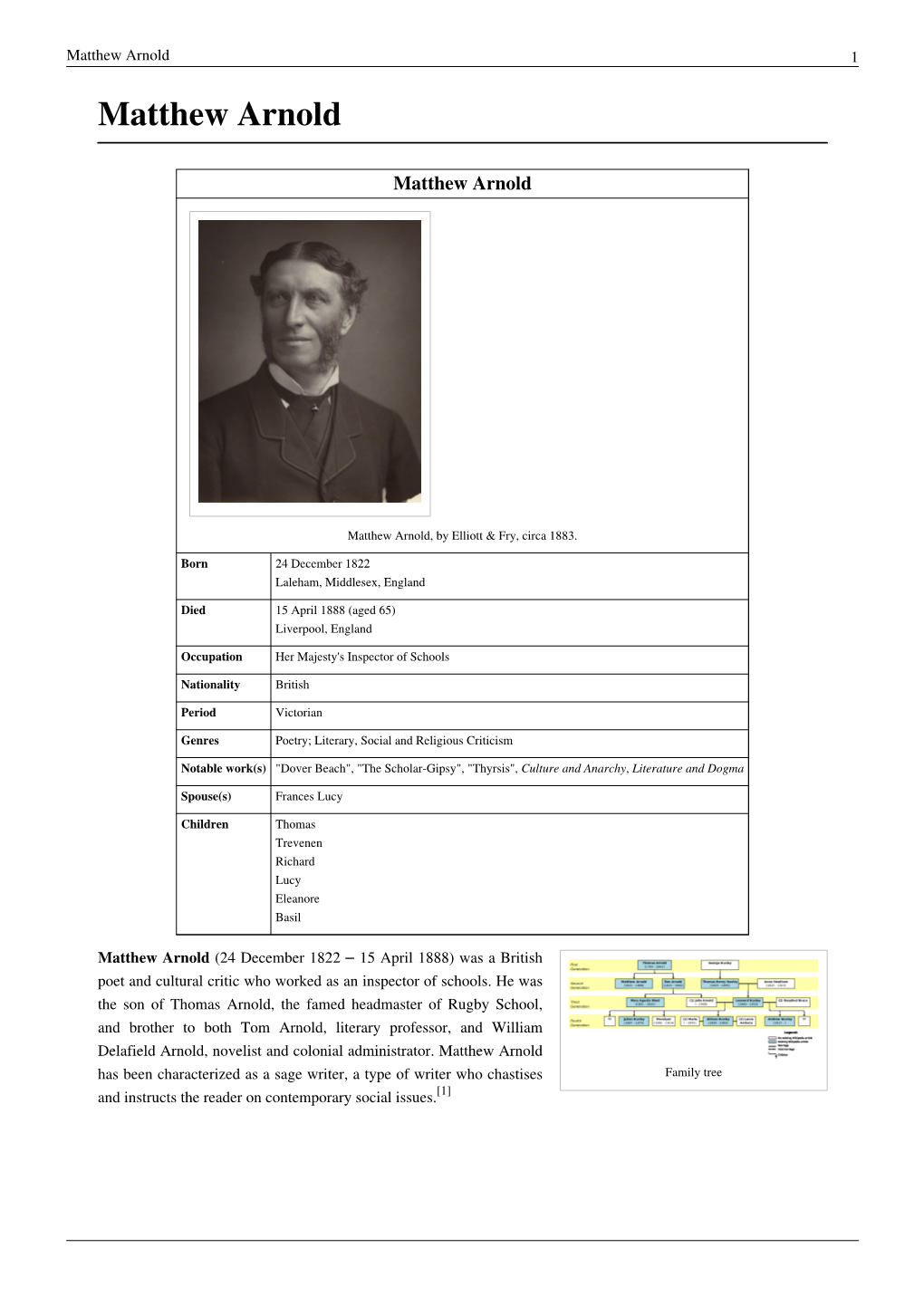

Matthew Arnold 1 Matthew Arnold

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yasha Gall, Julian Sorell Huxley, 1887-1975

Julian Sorell Huxley, 1887-1975 Yasha Gall Published by Nauka, St. Petersburg, Russia, 2004 Reproduced as an e-book with kind permission of Nauka Science editor: Academician AL Takhtajan Preface by the Science Editor The 20th century was the epoch of discovery in evolutionary biology, marked by many fundamental investigations. Of special significance were the works of AN Severtsov, SS Chetverikov, S Wright, JBS Haldane, G De Beer JS Huxley and R Goldschmidt. Among the general works on evolutionary theory, the one of greatest breadth was Julian Huxley’s book Evolution: The Modern Synthesis (1942). Huxley was one of the first to analyze the mechanisms of macro-evolutionary processes and discuss the evolutionary role of neoteny in terms of developmental genetics (the speed of gene action). Neoteny—the most important mechanism of heritable variation of ontogenesis—has great macro-evolutionary consequences. A Russian translation of Huxley’s book on evolution was prepared for publication by Professor VV Alpatov. The manuscript of the translation had already been sent to production when the August session of the VASKNIL in 1948 burst forth—a destructive moment in the history of biology in our country. The publication was halted, and the manuscript disappeared. I remember well a meeting with Huxley in 1945 in Moscow and Leningrad during the celebratory jubilee at the Academy of Sciences. He was deeply disturbed by the “blossoming” of Lysenkoist obscurantism in biology. It is also important to note that in the 1950s Huxley developed original concepts for controlling the birth rate of the Earth’s population. He openly declared the necessity of forming an international institute at the United Nations, since the global ecosystem already could not sustain the pressure of human “activity” and, together with humanity, might itself die. -

Letters from Arthur Penrhyn Stanley, (NLW MS 12877C.)

Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Cymorth chwilio | Finding Aid - Letters from Arthur Penrhyn Stanley, (NLW MS 12877C.) Cynhyrchir gan Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.0 Argraffwyd: Mai 08, 2017 Printed: May 08, 2017 Wrth lunio'r disgrifiad hwn dilynwyd canllawiau ANW a seiliwyd ar ISAD(G) Ail Argraffiad; rheolau AACR2; ac LCSH Description follows NLW guidelines based on ISAD(G) 2nd ed.; AACR2; and LCSH https://archifau.llyfrgell.cymru/index.php/letters-from-arthur-penrhyn-stanley archives.library .wales/index.php/letters-from-arthur-penrhyn-stanley Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru = The National Library of Wales Allt Penglais Aberystwyth Ceredigion United Kingdom SY23 3BU 01970 632 800 01970 615 709 [email protected] www.llgc.org.uk Letters from Arthur Penrhyn Stanley, Tabl cynnwys | Table of contents Gwybodaeth grynodeb | Summary information .............................................................................................. 3 Natur a chynnwys | Scope and content .......................................................................................................... 3 Nodiadau | Notes ............................................................................................................................................. 4 Pwyntiau mynediad | Access points ............................................................................................................... 4 Llyfryddiaeth | Bibliography .......................................................................................................................... -

Ttu Mac001 000057.Pdf (19.52Mb)

(Vlatthew flrnold. From the pn/ture in tlic Oriel Coll. Coniinon liooni, O.vford. Jhc Oxford poems 0[ attfiew ("Jk SAoUi: S'ips\i' ani "Jli\j«'vs.'') Illustrated, t© which are added w ith the storv of Ruskin's Roa(d makers. with Glides t© the Country the p©em5 iljystrate. Portrait, Ordnance Map, and 76 Photographs. by HENRY W. TAUNT, F.R.G.S. Photographer to the Oxford Architectural anid Historical Society. and Author of the well-knoi^rn Guides to the Thames. &c., 8cc. OXFORD: Henry W, Taunl ^ Co ALI. RIGHTS REStHVED. xji^i. TAONT & CO. ART PRINTERS. OXFORD The best of thanks is ren(iered by the Author to his many kind friends, -who by their information and assistance, have materially contributed to the successful completion of this little ^rork. To Mr. James Parker, -who has translated Edwi's Charter and besides has added notes of the greatest value, to Mr. Herbert Hurst for his details and additions and placing his collections in our hands; to Messrs Macmillan for the very courteous manner in which they smoothed the way for the use of Arnold's poems; to the Provost of Oriel Coll, for Arnold's portrait; to Mr. Madan of the Bodleian, for suggestions and notes, to the owners and occupiers of the various lands over which •we traversed to obtain some of the scenes; to the Vicar of New Hinksey for details, and to all who have helped with kindly advice, our best and many thanks are given. It is a pleasure when a ^ivork of this kind is being compiled to find so many kind friends ready to help. -

The Hero in the Poetry of Matthew

THE HERO IN THE POETRY OF MATTHEW ARNOLD APPROVED: v - ~ ' /X / TC. let >»- >- r y\ .. / ' tt: (,ic i f Major Frofessor Minor (Professor Director of eparturient, of English Dean of the Gradual.e Sch<x THE HERO IN THE POETRY OF MATTHEW ARNOLD THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Judith Dianne Mackey, B. A, Denton, Texas August, 1967 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Chapter I. FROM SCEPTICISM TO THE HEROIC CONCEPT: THE QUEST FOR INTELLECTUAL SECURITY .... 1 II. THE GENESIS OF A NEW SYNTHESIS 6 III. MATTHEW ARNOLD: THE EVOLUTION OF A STOIC 35 IV. MATTHEW ARNOLD: THE STOIC SYNTHESIS 62 V. CONCLUSION 113 BIBLIOGRAPHY 123 in CHAPTER I FROM SCEPTICISM TO THE HEROIC CONCEPT: THE QUEST FOR INTELLECTUAL SECURITY The nineteenth century constitutes, in the history of Western ideas, a period during which old beliefs and methods of thinking were questioned and criticized, and new intel- lectual and emotional responses to life were not yet firmly established. "Old institutions were undermined, new scien- tific discoveries appeared to be destroying the foundations of the Christian faith, as it was then conceived, and doubt -i like a grey mist spread over the whole field of thought." Evolutionary theories and Marxian Socialism shook the faith of the educated, and the Oxford Movement vainly attempted to create a new religious sentiment which could withstand the . 2 stress of these revolutionary ideas. In the wake of the destruction of old beliefs and ideas, violent and varying reactions occurred, primarily among the intelligentsia of the day. -

Tom Brown's Schooldays

TOM BROWN’S SCHOOLDAYS: DISCOVERING A VICTORIAN HEADMASTER IN RUGBY PUBLIC SCHOOL * CORTÉS GRANELL , Ana María Universitat de València Departament de Filologia Anglesa i Alemanya [email protected] Fecha de recepción: 11 de julio de 2013 Fecha de aceptación: 27 de julio de 2013 Título: Los días de escuela de Tom Brown: Descubriendo a un director victoriano en la Escuela Pública Rugby Resumen: Este artículo presenta la hipótesis que Thomas Arnold (1795-1842) mejoró y modeló al niño inglés medio para el Imperio Británico mientras que desempeñaba la función de director en la escuela pública Rugby (1828-1842). El estudio comienza por la introducción de la escuela pública en cuanto a su evolución y causas, además del nacimiento del mito de Arnold. La novela Tom Brown’s Schooldays de Thomas Hughes sirve para desarrollar nuestro entendimiento de lo genuino inglés a través del examen de una escuela pública modelo y sus constituyentes. Hemos realizado un análisis del personaje de Thomas Arnold mediante la comparación de un estudio de caso a partir de la novela de Hughes y dos películas adaptadas por Robert Stevenson (1940) y David Moore (2005). En las conclusiones ofrecemos la tesis que Thomas Arnold sólo pudo inculcar sus ideas por medio del antiguo sistema de los prefectos. Palabras clave: escuela pública, Rugby, Thomas Arnold, Thomas Hughes, inglés, prefecto. * This article was submitted for the subject Bachelor’s Degree Final Dissertation, and was supervised by Dr Laura Monrós Gaspar, lecturer in English Literature at the English and German Studies Department at the Universitat de València. Philologica Urcitana Revista Semestral de Iniciación a la Investigación en Filología Vol. -

Matthew Arnold

MATTHEW ARNOLD. THE POETICAL WORKS OF MATTHEW ARNOLD COMPLETE EDITION WITH BIOGRAPHICAL INTRODUCTION -OOX^OO- NEW YORK THOMAS Y. CROWELL & CO. PUBLISHERS COFYRIGHT, 1897, Bv T, Y. CROWELL & CO. Notbjooti IPnss J. S. Cushius & Co. - Berwick & Smith Norwood Masi. U.S.A. CONTENTS. PAGE NOTE . viii BIOGRAPHICAL INTRODUCTION ix BIBLIOGRAPHY xxiii EARLY POEMS. SONNETS:— Quiet Work I To a Friend . 2 Shakspeare 2 Written in Emerson's Essays 3 Written in Butler's Sermons 3 To the Duke of Wellington 4 " In Harmony with Nature " 5 To George Cruikshank 5 To a Republican Friend, 1848 . • . 6 Continued 7 Religious Isolation 7 MVCERINUS 8 THE CHURCH OF BROU : — I. The Castle 12 II. The Church 16 III. The Tomb 18 A MODERN SAPPHO 19 REQUIESCAT 21 YOUTH AND CALM 22 A MEMORY-PICTURE 23 THE NEW SIRENS 25 THE VOICE • • • 34 YOUTH'S AGITATIONS • • • 36 iv CONTENTS. PAGI THE WORLD'S TRIUMPHS 36 STAGIRIUS 37 HUMAN LIFE 39 TO A GYPSY CHILD BY THE SEASHORE ... 40 A QUESTION 43 IN UTRUMQUE PARATUS 43 THE WORLD AND THE QUIETIST 45 THE SECOND BEST A6 CONSOLATION .y RESIGNATION .g A DREAM c8 HoRATiAN ECHO eg NARRATIVE POEMS. SOHRAB AND RUSTUM gj THE SICK KING IN BOKHARA -.'... 88 BALDER DEAD: — I. Sending .... z: 11. Journey to the Dead j^g III. Funeral ' n6 TRISTRAM AND ISEULT: I. Tristram . 13^ II. Iseult of Ireland .... III. Iseult of Brittany SAINT BRANDAN ... * • 52 THE NECKAN * ' ^ 162 THE FORSAKEN MERMAN ' ' '^^ . 164 SONNETS. AUSTERITY OF POETRY A PICTURE AT NEWSTEAD . ' • • • 169 RACHEL: I., IL, in. , " ' * ' ' -'69 WORLDLY PLACE ' * • • • 170 • • , 172 CONTENTS. -

John Stuart Mill's Evaluations of Poetry

JOHN STUART MILL'S EVALUATIONS OF POETRY AND THEIR INFLUENCE UPON HIS INTELLECTUAL DEVELOPMENT by MILLO RUNDLE THOMPSON SHAW B.A., University of British Columbia, 1949 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of English We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1971 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of ENGLISH The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada Date October 1970 i JOHN STUART MILL'S EVALUATIONS OF POETRY AND THEIR INFLUENCE UPON HIS INTELLECTUAL DEVELOPMENT ABSTRACT The education of John Stuart Mill was one of the most unusual ever planned or experienced. Beginning with his learning Greek at the age of three and con• tinuing without a break of any kind to the age of four• teen, it constituted an almost total control of Mill's every waking activity, with the important exception of his visit to France at fourteen, until his appoint• ment to the East India Company in 1823. It emphasized the "tabula rasa" theory, the effect of external cir• cumstances on the developing mind, Hartley's Associa- tionist theory, and the judicious use of the Utilitarian theories of the "pleasure-pain" principle. -

The Scholar-Gipsy Study Material

The Scholar-Gipsy Study Material Summary “The Scholar-Gipsy” was written by poet and essayist Matthew Arnold in 1853. The poem is based on a story which was found in The Vanity of Dogmatizing (1661), written by Joseph Glanvil. The poem tells the story of a poor and disillusioned Oxford student who leaves university to join a group of traveling “gipsies” (Romani people). The Scholar-Gipsy wants not only to withdraw from his studies but also to withdraw from the modern world. He is so welcomed and becomes such a part of the "gipsy" family that they reveal some of their secrets to him. When he is discovered by two of his former Oxford peers, he tells them of how the Romani have their own unique way of learning. He plans to stay with them to learn as much as he can from them. He will then share their wisdom with the world, although he does not wish to return to that world himself. Arnold begins his poem by describing a rural setting just outside of Oxford. The speaker watches as a shepherd and reapers work in a field there. The speaker remains, enjoying the view of the fields and Oxford in the distance until the sun sets, his book lying beside him. Although the story (1661) was written two hundred years before the poem (1853), local people still claim to see the scholar-gipsy walking on the Berkshire moors: This said, he left them, and return'd no more.— But rumours hung about the country-side, That the lost Scholar long was seen to stray, Seen by rare glimpses, pensive and tongue-tied, In hat of antique shape, and cloak of grey, The same the gipsies wore. -

Unit 5: Matthew Arnold: “Literature and Science”

Unit 5 Matthew Arnold: “Literature and Science” UNIT 5: MATTHEW ARNOLD: “LITERATURE AND SCIENCE” UNIT STRUCTURE 5.1 Learning Objectives 5.2 Introduction 5.3 Matthew Arnold: Life and Works 5.4 Explanation of the Text 5.5 Major Themes 5.6 Style and Language 5.7 Let us Sum up 5.8 Further Reading 5.9 Answers to Check Your Progress 5.10 Model Questions 5.1 LEARNING OBJECTIVES After reading this unit you will be able to: • describe the life of Matthew Arnold • explain the context of the essay “Literature and Science” • analyse Arnold’s style and language • examine the contributions of Matthew Arnold as an essayist 5.2 INTRODUCTION This unit will give you an introduction to Matthew Arnold and provide you with a detailed study of the man, his life and his works. A detailed synopsis of the essay has also been included in this unit for a better understanding of the interrelation of literature and science. Over and 60 Alternative English (Block 1) Matthew Arnold: “Literature and Science” Unit 5 above, this unit aims to acquaint you with the themes that form a crucial part of the essay. Besides this, the unit shall also discuss the style and the language used by Arnold. 5.3 MATTHEW ARNOLD: LIFE AND WORKS Matthew Arnold has always been rated very highly among English essayist. It was through his essays that Arnold asserted his greatest influence on literature. His writing on the role of literary criticism in society advance classical ideas and advocate the adoption of universal aesthetic standards. -

John Buchan's Uncollected Journalism a Critical and Bibliographic Investigation

JOHN BUCHAN’S UNCOLLECTED JOURNALISM A CRITICAL AND BIBLIOGRAPHIC INVESTIGATION PART II CATALOGUE OF BUCHAN’S UNCOLLECTED JOURNALISM PART II CATALOGUE OF BUCHAN’S UNCOLLECTED JOURNALISM Volume One INTRODUCTION............................................................................................. 1 A: LITERATURE AND BOOKS…………………………………………………………………….. 11 B: POETRY AND VERSE…………………………………………………………………………….. 30 C: BIOGRAPHY, MEMOIRS, AND LETTERS………………………………………………… 62 D: HISTORY………………………………………………………………………………………………. 99 E: RELIGION……………………………………………………………………………………………. 126 F: PHILOSOPHY AND SCIENCE………………………………………………………………… 130 G: POLITICS AND SOCIETY……………………………………………………………………… 146 Volume Two H: IMPERIAL AND FOREIGN AFFAIRS……………………………………………………… 178 I: WAR, MILITARY, AND NAVAL AFFAIRS……………………………………………….. 229 J: ECONOMICS, BUSINESS, AND TRADE UNIONS…………………………………… 262 K: EDUCATION……………………………………………………………………………………….. 272 L: THE LAW AND LEGAL CASES………………………………………………………………. 278 M: TRAVEL AND EXPLORATION……………………………………………………………… 283 N: FISHING, HUNTING, MOUNTAINEERING, AND OTHER SPORTS………….. 304 PART II CATALOGUE OF BUCHAN’S UNCOLLECTED JOURNALISM INTRODUCTION This catalogue has been prepared to assist Buchan specialists and other scholars of all levels and interests who are seeking to research his uncollected journalism. It is based on the standard reference work for Buchan scholars, Robert G Blanchard’s The First Editions of John Buchan: A Collector’s Bibliography (1981), which is generally referred to as Blanchard. The catalogue builds on this work -

Matthewarnoldcul021369mbp.Pdf

landmarks in the History of Educati GENERAL EDIT o1 J. DOVER WILSON, Lrrr.D. Professor of Education in the University of London King's College F. A. CAVENAGH, M.A. Professor of Education at University College Swansea CULTURE AND ANARC landmarks in the History of Education GENERAL EDITO J. DOVER WILSON, Lrrr.D. Professor of Education in the University of London King's College F, A. CAVENAGH, M.A. Professor of Education at University College Swansea CULTURE AND ANARCHY LONDON Cambridge University Press FETTZS LANE NS"- YORK TORONTO ICJIBAY * CALCUTTA MADRAS Macmillan TOKYO Alartizen Company Ltd tAll rights reserved in the History ofEducation Cu.ture and Anarchy* BY MATTHEW ARNOLD Edited with an introduction by J. DOVER WILSON, Lirr.I Felh'W of the British Academy *7 CAMBRIDGE AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS 1932 PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN CONTENTS Editor's Preface ...... page vil Editor's Introduction . $ . xl AUTHOR'S PREFACE 3 INTRODUCTION 39 % Chapter I . , . SWEETNESS AND LIGHT a 43 Chapter II DOING AS ONE LIKES 72 Chapter III BARBARIANS, PHILISTINES, POPULATE . ^ Chapter IV HEBRAISM AND HELLENISM . .1,29 Chapter "V PORRO UNUM EST NECESSARIUM . .' "145 Chapter VI OUR LIBERAL PRACTITIONERS. 165 CONCLUSION ...... 202 Notes 213 * Bibliography . 239 To G. B. W. EDITOR'S PREFACE 9 * and Anarchy was first published as a book In 1869* and has never been reprinted In its original form; for when a second edition was called for in 1875 Arnold carefully revis%d the whole, corrected a few misprints, added a motto from the Vulgate on the back of the title-page, inserted the now familiar titles at the heads of the chapters, repara- graphed the text at many points, and, while developing Certain passages,, deleted or abridged a number of others. -

Approved Matthew Arnold As Revealed by His Letters, Poetry

Matthew Arnold as revealed by his letters, poetry, and criticism Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Yeager, Mabel Lee, 1910- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 26/09/2021 19:02:56 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/553248 Matthew Arnold as Revealed by His Letters, Poetry, and Criticism by Mabel Lee Yeager Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate College University of Arizona 1 9 3 5 Approved Major professor Date *• V* • ■ -:v * ; ~ ■ • > «• " ? ' « \ . < * £ < i m m i s Outline Cofi-A. A. Introduction B. The Three Tatthew Arnolds I. Arnold the Letter-' riter 1. Early life, 2. Work and marriage 3. Lectures in America 4. Salient characteristics and views 5. Depreciating attitude toward his contei poreries 6. Later life II. Arnold the Poet 1. Biographical references in his poetry 2. Dominant feeling of despair 3. Views on Christianity 4. Oxford, his period of youth 5. Nature, compared with ordsworth 6. Poetic criticism III. Arnold the Critic 1. Views on the function of criticism 2. Literary insight and critical perception 3. Observation of life and human nature 4. Repetition and use of stock phrases 5. Intellectuality and "superciliousness'’ 6. Satire C. Conclusion— That each of the three types of Arnold's writing reveals entirely different phases of his personality.