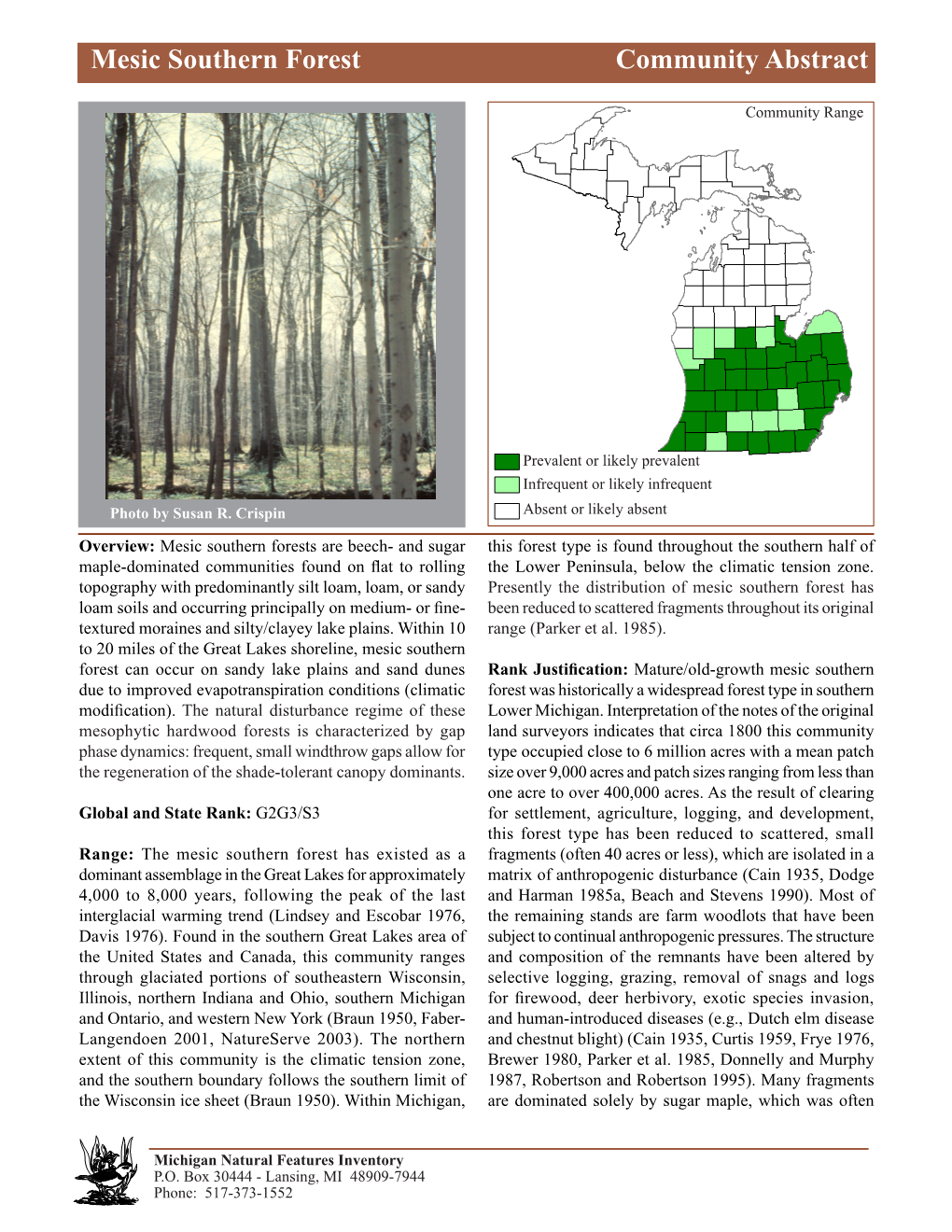

Mesic Southern Forest Communitymesic Southern Abstract Forest, Page 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Summary of Petroleum Plays and Characteristics of the Michigan Basin

DEPARTMENT OF INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY A summary of petroleum plays and characteristics of the Michigan basin by Ronald R. Charpentier Open-File Report 87-450R This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards and stratigraphic nomenclature. Denver, Colorado 80225 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT.................................................. 3 INTRODUCTION.............................................. 3 REGIONAL GEOLOGY.......................................... 3 SOURCE ROCKS.............................................. 6 THERMAL MATURITY.......................................... 11 PETROLEUM PRODUCTION...................................... 11 PLAY DESCRIPTIONS......................................... 18 Mississippian-Pennsylvanian gas play................. 18 Antrim Shale play.................................... 18 Devonian anticlinal play............................. 21 Niagaran reef play................................... 21 Trenton-Black River play............................. 23 Prairie du Chien play................................ 25 Cambrian play........................................ 29 Precambrian rift play................................ 29 REFERENCES................................................ 32 LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page 1. Index map of Michigan basin province (modified from Ells, 1971, reprinted by permission of American Association of Petroleum Geologists)................. 4 2. Structure contour map on top of Precambrian basement, Lower Peninsula -

What Climate Change Means for Michigan

August 2016 EPA 430-F-16-024 What Climate Change Means for Michigan Michigan’s climate is changing. Most of the state has Heavy Precipitation and Flooding warmed two to three degrees (F) in the last century. Changing the climate is likely to increase the frequency of floods in Heavy rainstorms are becoming more frequent, and Michigan. Over the last half century, average annual precipitation in ice cover on the Great Lakes is forming later or melting most of the Midwest has increased by 5 to 10 percent. But rainfall sooner. In the coming decades, the state will have during the four wettest days of the year has increased about 35 more extremely hot days, which may harm public percent. During the next century, spring rainfall and annual precipitation health in urban areas and corn harvests in rural areas. are likely to increase, and severe rainstorms are likely to intensify. Each Our climate is changing because the earth is warming. of these factors will tend to further increase the risk of flooding. People have increased the amount of carbon dioxide in the air by 40 percent since the late 1700s. Other heat-trapping greenhouse gases are also increasing. These gases have warmed the surface and lower atmosphere of our planet about one degree during the last 50 years. Evaporation increases as the atmo- sphere warms, which increases humidity, average rainfall, and the frequency of heavy rainstorms in many places—but contributes to drought in others. Heavy rains and snowmelt flooded the Tittabawassee River in Midland in April Greenhouse gases are also changing the world’s 2015. -

Guide to the Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- LILIACEAE

Guide to the Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- LILIACEAE LILIACEAE de Jussieu 1789 (Lily Family) (also see AGAVACEAE, ALLIACEAE, ALSTROEMERIACEAE, AMARYLLIDACEAE, ASPARAGACEAE, COLCHICACEAE, HEMEROCALLIDACEAE, HOSTACEAE, HYACINTHACEAE, HYPOXIDACEAE, MELANTHIACEAE, NARTHECIACEAE, RUSCACEAE, SMILACACEAE, THEMIDACEAE, TOFIELDIACEAE) As here interpreted narrowly, the Liliaceae constitutes about 11 genera and 550 species, of the Northern Hemisphere. There has been much recent investigation and re-interpretation of evidence regarding the upper-level taxonomy of the Liliales, with strong suggestions that the broad Liliaceae recognized by Cronquist (1981) is artificial and polyphyletic. Cronquist (1993) himself concurs, at least to a degree: "we still await a comprehensive reorganization of the lilies into several families more comparable to other recognized families of angiosperms." Dahlgren & Clifford (1982) and Dahlgren, Clifford, & Yeo (1985) synthesized an early phase in the modern revolution of monocot taxonomy. Since then, additional research, especially molecular (Duvall et al. 1993, Chase et al. 1993, Bogler & Simpson 1995, and many others), has strongly validated the general lines (and many details) of Dahlgren's arrangement. The most recent synthesis (Kubitzki 1998a) is followed as the basis for familial and generic taxonomy of the lilies and their relatives (see summary below). References: Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (1998, 2003); Tamura in Kubitzki (1998a). Our “liliaceous” genera (members of orders placed in the Lilianae) are therefore divided as shown below, largely following Kubitzki (1998a) and some more recent molecular analyses. ALISMATALES TOFIELDIACEAE: Pleea, Tofieldia. LILIALES ALSTROEMERIACEAE: Alstroemeria COLCHICACEAE: Colchicum, Uvularia. LILIACEAE: Clintonia, Erythronium, Lilium, Medeola, Prosartes, Streptopus, Tricyrtis, Tulipa. MELANTHIACEAE: Amianthium, Anticlea, Chamaelirium, Helonias, Melanthium, Schoenocaulon, Stenanthium, Veratrum, Toxicoscordion, Trillium, Xerophyllum, Zigadenus. -

Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description

Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description Prepared by: Michael A. Kost, Dennis A. Albert, Joshua G. Cohen, Bradford S. Slaughter, Rebecca K. Schillo, Christopher R. Weber, and Kim A. Chapman Michigan Natural Features Inventory P.O. Box 13036 Lansing, MI 48901-3036 For: Michigan Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Division and Forest, Mineral and Fire Management Division September 30, 2007 Report Number 2007-21 Version 1.2 Last Updated: July 9, 2010 Suggested Citation: Kost, M.A., D.A. Albert, J.G. Cohen, B.S. Slaughter, R.K. Schillo, C.R. Weber, and K.A. Chapman. 2007. Natural Communities of Michigan: Classification and Description. Michigan Natural Features Inventory, Report Number 2007-21, Lansing, MI. 314 pp. Copyright 2007 Michigan State University Board of Trustees. Michigan State University Extension programs and materials are open to all without regard to race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, marital status or family status. Cover photos: Top left, Dry Sand Prairie at Indian Lake, Newaygo County (M. Kost); top right, Limestone Bedrock Lakeshore, Summer Island, Delta County (J. Cohen); lower left, Muskeg, Luce County (J. Cohen); and lower right, Mesic Northern Forest as a matrix natural community, Porcupine Mountains Wilderness State Park, Ontonagon County (M. Kost). Acknowledgements We thank the Michigan Department of Natural Resources Wildlife Division and Forest, Mineral, and Fire Management Division for funding this effort to classify and describe the natural communities of Michigan. This work relied heavily on data collected by many present and former Michigan Natural Features Inventory (MNFI) field scientists and collaborators, including members of the Michigan Natural Areas Council. -

Phylogenetic Placement of the Enigmatic Orchid Genera Thaia and Tangtsinia: Evidence from Molecular and Morphological Characters

TAXON 61 (1) • February 2012: 45–54 Xiang & al. • Phylogenetic placement of Thaia and Tangtsinia Phylogenetic placement of the enigmatic orchid genera Thaia and Tangtsinia: Evidence from molecular and morphological characters Xiao-Guo Xiang,1 De-Zhu Li,2 Wei-Tao Jin,1 Hai-Lang Zhou,1 Jian-Wu Li3 & Xiao-Hua Jin1 1 Herbarium & State Key Laboratory of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100093, P.R. China 2 Key Laboratory of Biodiversity and Biogeography, Kunming Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, Yunnan 650204, P.R. China 3 Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Menglun Township, Mengla County, Yunnan province 666303, P.R. China Author for correspondence: Xiao-Hua Jin, [email protected] Abstract The phylogenetic position of two enigmatic Asian orchid genera, Thaia and Tangtsinia, were inferred from molecular data and morphological evidence. An analysis of combined plastid data (rbcL + matK + psaB) using Bayesian and parsimony methods revealed that Thaia is a sister group to the higher epidendroids, and tribe Neottieae is polyphyletic unless Thaia is removed. Morphological evidence, such as plicate leaves and corms, the structure of the gynostemium and the micromorphol- ogy of pollinia, also indicates that Thaia should be excluded from Neottieae. Thaieae, a new tribe, is therefore tentatively established. Using Bayesian and parsimony methods, analyses of combined plastid and nuclear datasets (rbcL, matK, psaB, trnL-F, ITS, Xdh) confirmed that the monotypic genus Tangtsinia was nested within and is synonymous with the genus Cepha- lanthera, in which an apical stigma has evolved independently at least twice. -

Round-Lobed Hepatica (Anemone Americana) – Wooly Harbinger of Spring

Round-lobed Hepatica (Anemone americana) – Wooly Harbinger of Spring Did you Know? Hepaticas are one of the first flowers to bloom in Spring. Native Americans used a tea derived from the leaves to cure a number of ailments. Hepaticas are poisonous in large doses. They can also be irritating to the skin if handled. Photo : 2013 Brian Popelier Habitat – Upland woods and forests, deciduous forests Size – 70-170 cm in height Range – Manitoba, Ontario and Quebec south into the eastern United States Flowering Date – March - May Status – S5/ Common in Ontario Other Common Names – Liverleaf, Snow Trillium, Blue Anemone, Kidneywort The Bruce Trail Conservancy | PO Box 857 Hamilton, ON L8N 3N9 | 1.800.665.4453 | [email protected] Identification: Purple, pink or white six - ten petaled flowers sit atop a single, leafless stem covered in wooly hairs. Flowers often found in clumps. The leaves are distinct with three lobes ending in a rounded tip. The flower stocks are upright standing over the flattened basal leaves. The leaves are light green at first but turn a purplish, wine colour as the season wears on and can often be seen standing out from the snow in the winter. Photo : 2013 Brian Popelier Interesting Facts The plant gets its name from the leathery purple-brown basal leaves, which resemble the shape of the liver. Many early herbalists believed that the shape of the plant determined its usefulness in the treatment of liver ailments. Bees and flies are the primary pollinators. The plant uses ants to distribute their seeds. As the seeds drop ants pick them up and disperse the seeds to other areas. -

Ranunculaceae) for Asian and North American Taxa

Mosyakin, S.L. 2018. Further new combinations in Anemonastrum (Ranunculaceae) for Asian and North American taxa. Phytoneuron 2018-55: 1–11. Published 13 August 2018. ISSN 2153 733X FURTHER NEW COMBINATIONS IN ANEMONASTRUM (RANUNCULACEAE) FOR ASIAN AND NORTH AMERICAN TAXA SERGEI L. MOSYAKIN M.G. Kholodny Institute of Botany National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine 2 Tereshchenkivska Street Kiev (Kyiv), 01004 Ukraine [email protected] ABSTRACT Following the proposed re-circumscription of genera in the group of Anemone L. and related taxa of Ranunculaceae (Mosyakin 2016, Christenhusz et al. 2018) and based on recent molecular phylogenetic and partly morphological evidence, the genus Anemonastrum Holub is recognized here in an expanded circumscription (including Anemonidium (Spach) Holub, Arsenjevia Starod., Tamuria Starod., and Jurtsevia Á. Löve & D. Löve) covering members of the “Anemone ” clade with x=7, but excluding Hepatica Mill., a genus well outlined morphologically and forming a separate subclade (accepted by Hoot et al. (2012) as Anemone subg. Anemonidium (Spach) Juz. sect. Hepatica (Mill.) Spreng.) within the clade earlier recognized taxonomically as Anemone subg. Anemonidium (sensu Hoot et al. 2012). The following new combinations at the section and subsection ranks are validated: Anemonastrum Holub sect. Keiskea (Tamura) Mosyakin, comb. nov . ( Anemone sect. Keiskea Tamura); Anemonastrum [sect. Keiskea ] subsect. Keiskea (Tamura) Mosyakin, comb. nov .; Anemonastrum [sect. Keiskea ] subsect. Arsenjevia (Starod.) Mosyakin, comb. nov . ( Arsenjevia Starod.); and Anemonastrum [sect. Anemonastrum ] subsect. Himalayicae (Ulbr.) Mosyakin, comb. nov. ( Anemone ser. Himalayicae Ulbr.). The new nomenclatural combination Anemonastrum deltoideum (Hook.) Mosyakin, comb. nov . ( Anemone deltoidea Hook.) is validated for a North American species related to East Asian Anemonastrum keiskeanum (T. -

Etude Sur L'origine Et L'évolution Des Variations Florales Chez Delphinium L. (Ranunculaceae) À Travers La Morphologie, L'anatomie Et La Tératologie

Etude sur l'origine et l'évolution des variations florales chez Delphinium L. (Ranunculaceae) à travers la morphologie, l'anatomie et la tératologie : 2019SACLS126 : NNT Thèse de doctorat de l'Université Paris-Saclay préparée à l'Université Paris-Sud ED n°567 : Sciences du végétal : du gène à l'écosystème (SDV) Spécialité de doctorat : Biologie Thèse présentée et soutenue à Paris, le 29/05/2019, par Felipe Espinosa Moreno Composition du Jury : Bernard Riera Chargé de Recherche, CNRS (MECADEV) Rapporteur Julien Bachelier Professeur, Freie Universität Berlin (DCPS) Rapporteur Catherine Damerval Directrice de Recherche, CNRS (Génétique Quantitative et Evolution Le Moulon) Présidente Dario De Franceschi Maître de Conférences, Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle (CR2P) Examinateur Sophie Nadot Professeure, Université Paris-Sud (ESE) Directrice de thèse Florian Jabbour Maître de conférences, Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle (ISYEB) Invité Etude sur l'origine et l'évolution des variations florales chez Delphinium L. (Ranunculaceae) à travers la morphologie, l'anatomie et la tératologie Remerciements Ce manuscrit présente le travail de doctorat que j'ai réalisé entre les années 2016 et 2019 au sein de l'Ecole doctorale Sciences du végétale: du gène à l'écosystème, à l'Université Paris-Saclay Paris-Sud et au Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle de Paris. Même si sa réalisation a impliqué un investissement personnel énorme, celui-ci a eu tout son sens uniquement et grâce à l'encadrement, le soutien et l'accompagnement de nombreuses personnes que je remercie de la façon la plus sincère. Je remercie très spécialement Florian Jabbour et Sophie Nadot, mes directeurs de thèse. -

Bovine Fascioliasis with Emphasis on Fasciola Hepatica

PEER REVIEWED Bovine fascioliasis with emphasis on Fasciola hepatica Gary L. Zimmerman, MS, PhD, DVM 1106 West Park 424, Livingston, MT 59047 Corresponding author: Gary L. Zimmerman, [email protected], 406-223-3704 Abstract over 135 million years, with the divergent evolution of Fasciola hepatica and F. gigantica occurring ap Fasciola hepatica, the common liver fluke, is an proximately 19 million years ago. 14 In the continental economically important parasite of ruminants. Although United States, Fasciola hepatica is the most common and infections in cattle are generally chronic and sub-clinical, economically important fluke infecting domestic large the overall impacts on health and productivity can be and small ruminants. The related species F. gigantica, significant, including decreased feed efficiency, weight which is common worldwide, has also been reported in 24 32 gain, reproductive rates, immunity, immunodiagnostic the southeastern United States. • Fascioloides magna, tests, and responses to vaccinations. Acute infections normally a parasite of deer, elk, and moose, also occurs can occur in cattle, but are more common in sheep. There in cattle as an incidental finding at necropsy or slaugh 9 38 are no pathognomonic signs of fascioliasis. Fecal ex ter, whereas in sheep it is often fatal. • Previously aminations using sedimentation or filtration techniques reported to infect Bison bison, recent research efforts remain the most commonly used diagnostic tools. In the to experimentally infect bison with Fascioloides magna United States, albendazole and a combined clorsulon/ have not been successful.10,38 Dicrocoelium dendriticum ivermectin formulation are the only currently approved is a smaller and less pathogenic liver fluke ofruminants products for treatment of liver flukes. -

Murder-Suicide Ruled in Shooting a Homicide-Suicide Label Has Been Pinned on the Deaths Monday Morning of an Estranged St

-* •* J 112th Year, No: 17 ST. JOHNS, MICHIGAN - THURSDAY, AUGUST 17, 1967 2 SECTIONS - 32 PAGES 15 Cents Murder-suicide ruled in shooting A homicide-suicide label has been pinned on the deaths Monday morning of an estranged St. Johns couple whose divorce Victims had become, final less than an hour before the fatal shooting. The victims of the marital tragedy were: *Mrs Alice Shivley, 25, who was shot through the heart with a 45-caliber pistol bullet. •Russell L. Shivley, 32, who shot himself with the same gun minutes after shooting his wife. He died at Clinton Memorial Hospital about 1 1/2 hqurs after the shooting incident. The scene of the tragedy was Mrsy Shivley's home at 211 E. en name, Alice Hackett. Lincoln Street, at the corner Police reconstructed the of Oakland Street and across events this way. Lincoln from the Federal-Mo gul plant. It happened about AFTER LEAVING court in the 11:05 a.m. Monday. divorce hearing Monday morn ing, Mrs Shivley —now Alice POLICE OFFICER Lyle Hackett again—was driven home French said Mr Shivley appar by her mother, Mrs Ruth Pat ently shot himself just as he terson of 1013 1/2 S. Church (French) arrived at the home Street, Police said Mrs Shlv1 in answer to a call about a ley wanted to pick up some shooting phoned in fromtheFed- papers at her Lincoln Street eral-Mogul plant. He found Mr home. Shivley seriously wounded and She got out of the car and lying on the floor of a garage went in the front door* Mrs MRS ALICE SHIVLEY adjacent to -• the i house on the Patterson got out of-'the car east side. -

The Urban Geography of Saginaw, Michigan

Wayne State University Wayne State University Theses 1-1-1933 The rbU an Geography of Saginaw, Michigan Dennis Glenn Cooper Wayne State University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_theses Part of the Geography Commons, History Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Cooper, Dennis Glenn, "The rU ban Geography of Saginaw, Michigan" (1933). Wayne State University Theses. Paper 465. This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. THE URBAN GEOGRAPHY OF SAGINAW, MICHIGAN A Thesis SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE COLLEGES OF THE CITY OF DETROIT IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS. BY Dennis Glen Cooper Detroit, Michigan 1933 t a b l e o f c o n t e n t s I. O u t l i n e ...................... ill II. List of maps, graphs, ana pictures............. vi III. THE URBAN GEOGRAPHY OF SAG INAL, MICHIGAN. 1 IV. Appendix . .......... « . .... 59 V. Bibliography ....................... • 62 f ii THE URBAN GEOGRAPHY OF SAGINAW, MICHIGAN. Outline Page A. Outstanding characteristics of the city............ • 1 1, Unusual landscape pattern with tvvc distinct nuclei 2. Industrial development in transition stage between period of extractive activities and diversified industries B. General situation: the Saginaw Basin • *.*•••* 2 1. Topography 2. Soil 3* Climate 4, Natural resources 5, Drainage C* Site • 4 1* Position of glacial moraine crossing valley 2. Bluff cut in moraine at outer bend and on west side of river 3. -

Anemone Acutiloba – Hepatica

Friends of the Arboretum Native Plant Sale Anemone acutiloba – Hepatica COMMON NAME: Hepatica, Sharp-lobed hepatica SCIENTIFIC NAME: Anemone acutiloba – the Greek word anemos is wind and acutiloba refers to the pointed leaves. The common name of hepatica comes from the fancied resemblance of the 3-lobed leaves to the liver. FLOWER: white, pink, lavender with six (usually) petal-like sepals. The color tends to fade with age. BLOOMING PERIOD: April, but maybe March with global warming! This is one of the earliest spring flowers. SIZE: 4 to 6 inches BEHAVIOR: This is a perennial herb with its distinctive 3-lobed leaves and fibrous roots. It will spread from seed and should be divided in fall. SITE REQUIREMENTS: Does best in rich, moist soil and dense shade of maple forests, but tolerates less shady habitats and drier, rocky soils. Look for it on steep, rocky hillsides and steep banks of creeks. NATURAL RANGE; Nova Scotia to northern Florida, west to Manitoba, Iowa, Missouri and even in Alaska. In Wisconsin it is more common in the southern 2/3 of the state. SPECIAL FEATURES: Old leaves may still be present in early spring, but will be looking kind of coppery. Then furry stems unfurl and hold the fragrant pastel flowers. The new leaves appear after flowering and will remain sort of green until the following spring. SUGGESTED CARE: Provide ample water in spring and fall, especially the first few years. Cover in winter with light mulch of maple leaves, but remove the mulch in mid to late March. COMPANION PLANTS: trillium, Solomon’s plume, toothwort, Dutchman’s breeches, spring beauty, wild geranium, bloodroot, troutlily, bedstraw, rue anemone SPECIAL NOTE: There is a similar specials, Anemone Americana, with round-lobed leaves.