Report of the Karnal District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GOVERNMENT of UTTAR PRADESH Public Works Department Public Disclosure Authorized

GOVERNMENT OF UTTAR PRADESH Public Works Department Public Disclosure Authorized Uttar Pradesh Core Road Network Development Program Part – A: Project Preparation DETAILED PROJECT REPORT Volume - IX: Updated Resettlement Action Plan Gola – Shahjahanpur Road (SH-93) Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized August 2018 India Consulting engineers pvt. ltd. Uttar Pradesh Core Road Network Development Program DETAILED PROJECT REPORT Volume-IX : Updated Resettlement Action Plan Gola – Shahjahanpur Road (SH-93) Volume-IX : Updated Resettlement Action Plan Document Name (Detailed Project Report) Document Number EIRH1UP020/DPR/SH-93/GS/004/IX Uttar Pradesh Core Road Network Development Program Project Name Part – A: Project Preparation including Detailed Engineering Design and Contract Documentation Project Number EIRH1UP020 Document Authentication Name Designation Prepared by Dr. Sudesh Kaul Social Development Specialist Reviewed by Rajeev Kumar Gupta Deputy Team Leader Approved by Rick Camise Team Leader History of Revisions Version Date Description of Change(s) Rev. 0 19/12/2014 First Submission Rev. 1 29/12/2014 Second submission with LA Rev. 2 14/01/2015 Compliances to WB Comments Rev. 3 08/07/2015 Compliances to Review Consultant Comments Rev. 4 14/08/2018 Compliances to WB comments for Updated RAP Page i| Rev: R4 Uttar Pradesh Core Road Network Development Program DETAILED PROJECT REPORT Volume-IX : Updated Resettlement Action Plan Gola – Shahjahanpur Road (SH-93) TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Description -

Sensitive Space Along the India-Bangladesh Border

THE FRAGMENTS AND THEIR NATION(S): SENSITIVE SPACE ALONG THE INDIA-BANGLADESH BORDER A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Jason Cons January 2011 © 2011 Jason Cons THE FRAGMENTS AND THEIR NATION(S): SENSITIVE SPACE ALONG THE INDIA-BANGLADESH BORDER Jason Cons, Ph.D. Cornell University 2011 Borders are often described as “sensitive” areas—exceptional and dangerous spaces at once central to national imaginaries and at the limits of state control. Yet what does sensitivity mean for those who live in, and those who are in charge of regulating, such spaces? Why do these areas persist as spaces of conflict and confusion? This dissertation explores these questions in relation to a series of enclaves—sovereign pieces of India inside of Bangladesh and vice versa—clustered along the Northern India–Bangladesh border. In it, I develop the notion of “sensitivity” as an analytic for understanding spaces like the enclaves, showing how they are zones within which postcolonial fears about sovereignty, security, identity, and national survival become mapped onto territory. I outline the politics of sensitivity and the production of sensitive space through both historical and ethnographic research. First, I explore the ways that ambiguity and vague fears about security and citizenship emerge as forms of moral regulation within and in relation to the enclaves. Specifically, I interrogate the processes through which information about the enclaves is regulated and policed and the ambiguity, suspicion, and insecurity that emerge out of such practices. -

History of North East India (1228 to 1947)

HISTORY OF NORTH EAST INDIA (1228 TO 1947) BA [History] First Year RAJIV GANDHI UNIVERSITY Arunachal Pradesh, INDIA - 791 112 BOARD OF STUDIES 1. Dr. A R Parhi, Head Chairman Department of English Rajiv Gandhi University 2. ************* Member 3. **************** Member 4. Dr. Ashan Riddi, Director, IDE Member Secretary Copyright © Reserved, 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this publication which is material protected by this copyright notice may be reproduced or transmitted or utilized or stored in any form or by any means now known or hereinafter invented, electronic, digital or mechanical, including photocopying, scanning, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without prior written permission from the Publisher. “Information contained in this book has been published by Vikas Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. and has been obtained by its Authors from sources believed to be reliable and are correct to the best of their knowledge. However, IDE—Rajiv Gandhi University, the publishers and its Authors shall be in no event be liable for any errors, omissions or damages arising out of use of this information and specifically disclaim any implied warranties or merchantability or fitness for any particular use” Vikas® is the registered trademark of Vikas® Publishing House Pvt. Ltd. VIKAS® PUBLISHING HOUSE PVT LTD E-28, Sector-8, Noida - 201301 (UP) Phone: 0120-4078900 Fax: 0120-4078999 Regd. Office: 7361, Ravindra Mansion, Ram Nagar, New Delhi – 110 055 Website: www.vikaspublishing.com Email: [email protected] About the University Rajiv Gandhi University (formerly Arunachal University) is a premier institution for higher education in the state of Arunachal Pradesh and has completed twenty-five years of its existence. -

Integrated Natural and Human Resources Appraisal of Jaisalmer District

CAZRI Publication No. 39 INTEGRATED NATURAL AND HUMAN RESOURCES APPRAISAL OF JAISALMER DISTRICT Edited by P.C. CHATTERJI & AMAL KAR mw:JH9 ICAR CENTRAL ARID ZONE RESEARCH INSTITUTE JODHPUR-342 003 1992 March 1992 CAZRI Publication No. 39 PUBLICA nON COMMITTEE Dr. S. Kathju Chairman Dr. P.C. Pande Member Dr. M.S. Yadav Member Mr. R.K. Abichandani Member Dr. M.S. Khan Member Mr. A. Kar .Member Mr. Gyanchand Member Dr. D.L. Vyas Sr. A.D. Mr. H.C. Pathak Sr. F. & Ac.O. Published by the Director Central Arid 20he Research In.Hitute, Jodhpur-342 003 * Printed by MIs Cheenu Enterprises, Navrang, B-35 Shastri Nagar, Jodhpur-342 003 , at Rajasthan Law Weekly Press, High Court Road, Jodhpur-342 001 Ph. 23023 CONTENTS Page Foreword- iv Preface v A,cknowledgements vi Contributors vii Technical support viii Chapter I Introduction Chapter II Climatic features 5 Chapter III Geological framework 12 Chapter- IV Geomorphology 14 ChapterY Soils and land use capability 26 Chapter VI Vegetation 35 Chapter VII Surface water 42 Chapter Vill Hydrogeological conditions 50 Chapter IX Minetal resources 57 Chapter X Present land use 58 Chapter XI Socio-economic conditions 62 Chapter XII Status of livestock 67 Chapter X III Wild life and rodent pests 73 Chapter XLV Major Land Resources Units: Characteristics and asse%ment 76 Chapter XV Recommendations 87 Appendix I List of villages in Pokaran and laisalmer Tehsils, laisalmer district, alongwith Major Land Resources Units (MLRU) 105 Appendix II List of villages facing scarcity of drinking water in laisalmer district 119 Appendix III New site~ for development of Khadins in Iaisalmer district ]20 Appendix IV Sites for construction of earthen check dams, anicuts and gully control structures in laisalmer district 121 Appendix V Natural resources of Sam Panchayat Samiti 122 CAZRI Publications , . -

Settlement of East Bengal Refugees in Tea Gardens of South Assam on Historical Perspective (1947-1960)

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention (IJHSSI) ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 9 Issue 5 Ser. II || May 2020 || PP 38-43 Settlement of East Bengal Refugees in Tea Gardens of South Assam on Historical Perspective (1947-1960) Leena Chakrabarty Assistant Professor, Department of History Ramkrishnanagar College,Ramkrishna Nagar,Karimganj,Assam Abstract: After partition of India in 1947, large number of refugees , victims of communal riot in East Bengal ,took shelter in Barak valley of Assam as it was socially, culturally and geographically adjacent to Sylhet. The condition of these uprooted people was very miserable who left behind their ancestral property. It was a very difficult task on the part of the Government to provide rehabilitation of the refugees. However with the effort of the Central Government colonies were established for the rehabilitation of the refugees. Indian Tea Association (ITA) extended their helping hand in this regard and allotted surplus land for the settlement of the refugees. In Barak Valley initially in 83 tea gardens refugees were given rehabilitation. The paper will deal in depth with the rehabilitation of the refugees in ITA colonies in South of Assam based on primary and secondary sources. Key words: Communal riot, Refugee, Rehabilitation, ITA , Development, partition ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- Date of Submission: 06-05-2020 Date -

Land Revenue and Land Reforms in the Post

Imperial Journal of Interdisciplinary Research (IJIR) Vol-2, Issue-11, 2016 ISSN: 2454-1362, http://www.onlinejournal.in Land –Related Problems and Socio- Political Tension in Bengal: Special Reference to Jalpaiguri District (1947- 2004) Dr. Kartik Chandra Sutradhar, Netaji Subhas Mahavidyalayay, Haldibari, Cooch Behar Abstract: During the Colonial period the agrarian many benevolent zamindars lost their zamindari by systems and agrarian structure were changed in the law of ‘Sun Set’, many peasants must sell their the different parts of India by introducing various lands and became sharecroppers or labourers due to systems, such as Permanent Settlement, Raiyotwari heavy indebtedness. Lands were utilized for Settlement, Mahalwari Settlement and in some commercial purposes by introducing cultivation of parts of Bengal and India as well lands were commercial crops like jute, tobacco, tea, blue, etc. declared as waste lands where British- India Govt. The cultivation of commercial crops was profitable, was the proprietor of the lands declaring but the profit was obtained by the zamindars, Government Khasmahal. Whatever settlement was jotdars, intermediaries, mahajans and ultimately introduced, everywhere the peasants, particularly the Britishers depriving cultivators. In a nutshell, it the small peasants, sharecroppers and agricultural can be said that the feudal system in agrarian field labourers were exploited and deprived was strong during the colonial period as because tremendously in the colonial- agrarian – economy. five or six stages -

48209-001: Medha Energy Private Limited Initial Environmental

Initial Environmental Examination Project Number: 48209 December 2014 IND: 20 MW Solar Power Project Medha Energy Private Limited Prepared by AECOM India Private Limited for ACME Gurgaon Power Private Limited The initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “Terms of Use” section of this website. Environment Submitted by: AECOM 9th Floor, Infinity Tower C, DLF Cybercity, DLF Phase II, Gurgaon, India 122002. November 2014 EnvironmentandSocialImpactAssessmentReport 20MWSolarPowerProject MedhaEnergyPrivateLimited BariSeer,JodhpurDistrict,Rajasthan FINALREPORT Environmental and Social Impact Assessment: Page | i 20 MW Solar Power Project- MEPL Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... 11 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 20 1.1 Project Background .......................................................................................................... 20 1.2 Purpose and Scope of Study ............................................................................................. 21 1.3 Approach and Methodology ............................................................................................. 21 1.4 Agencies contacted ......................................................................................................... -

Land Administration and Its Impact on Economic Development

REAL ESTATE AND PLANNING, HENLEY BUSINESS SCHOOL Land Administration and Its Impact on Economic Development A thesis submitted to the fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Gandhi Prasad Subedi April, 2016 Declaration I confirm that this is my own work and the use of all material from other sources has been properly and fully acknowledged. ............................................. Gandhi Prasad Subedi April, 2016 i Abstract This thesis investigates the relationship between land administration and economic development. More specifically, it assesses the role of land tenure security in productivity and that of land administration services in revenue generation. The empirical part of the study was undertaken in Nepal, Bangladesh and Thailand. A mixed method approach was employed for data collection, analysis and interpretation. The information was gathered using questionnaires, interviews, observations, informal discussions and documentation analysis. This study demonstrates that land administration plays a crucial role in providing security of land tenure. It also evidences that the use value, collateral value and exchange value of land is increased after registration which has benefitted the occupation, investment and finance sectors of the case study economies. Specifically, it was found that land use activity became more productive. With regard to financial services, banks more readily accepted land as loan security for debt finance and did so at an interest rate that was lower than that offered by private lenders. Land-related investment and income also increased and these effects are found to be positively correlated with tenure security. However, access to credit is not enough to increase investment unless it is communicated properly. -

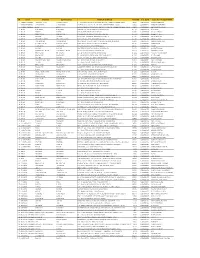

Sn State District Sub-District Branch Address Pincode

SN STATE DISTRICT SUB-DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS PINCODE IFSC CODE CONTACT PERSON NAME 1 ANDHRA PRADESH VISHAKAPATNAM VISHAKAPATNAM 47-10-20, DWARAKAPLAZA, DWARAKANAGAR, ANDHRA PRADESH-530001 530001 UCBA0000118 KAMMILA ELESWARI 2 ANDHRA PRADESH VIJAYAWADA VIJAYAWADA (POST BOX NO. 328),, D. NO. 27/18/47,, ANDHRA PRADESH-520002 520002 UCBA0000222 RAMISETTY SRAVANTHI 3 ANDHRA PRADESH ELURU ELURU SRI RAMA BHADRA COPLX, DNO 22B-12-10,GADEVARI, ANDHRA PRADESH-534001 534001 UCBA0000491 BHAVANIBANAVATHU 4 BIHAR BEGUSARAI BEGUSARAI MARWARI MOHALLA, MAIN ROAD, BIHAR-851101 851101 UCBA0000239 SHIKHA RAJ 5 BIHAR PURNEA PURNEA NEW MARKET, PURNEA, BIHAR-854301 854301 UCBA0000308 SURUCHI VERMA 6 BIHAR KISHANGANJ KISHANGANJ GANDHI CHOWK, KISHANGANJ, BIHAR-855108 855108 UCBA0000340 SHREEKANT JHA 7 BIHAR MUNGER MUNGER PO BOX NO. 7, BEKAPUR, BEKAPUR, BIHAR-811201 811201 UCBA0000428 KULA NAND JHA 8 BIHAR KHAGARIA - BIHAR KHAGARIA - BIHAR STATION ROAD, KHAGARIA, BIHAR-851201 851201 UCBA0001494 KIRAN KUMARI 9 BIHAR GAIYARI-BIHAR GAIYARI-BIHAR VILL-GAIYARI, PO-ZERO, MILE CHOWK ARARIA,PURN, BIHAR-854311 854311 UCBA0001614 RAKESH KUMAR RAM 10 BIHAR SAHARSA - BIHAR SAHARSA - BIHAR DHRAMSHALA ROAD, SAHARSA, BIHAR-852201 852201 UCBA0001822 AMRIT KUMAR 11 BIHAR SAMASTIPUR SAMASTIPUR GOLA ROAD, SAMASTIPUR, BIHAR-848101 848101 UCBA0001926 ANKUR 12 BIHAR KATIHAR KATIHAR VINODPUR,CHUNA GALI, KATIHAR, BIHAR-854105 854105 UCBA0002255 ANURAG RAMAN 13 BIHAR MADHEPURA - BIHAR MADHEPURA - BIHAR MAIN ROAD, MADHEPURA, BIHAR-852113 852113 UCBA0002292 ANUPRIYA KUMARI 14 BIHAR BHAGALPUR -

Social Monitoring Report India: Himachal Pradesh Clean Energy

Social Monitoring Report Semestral Report: January 2020 – June 2020 May 2021 India: Himachal Pradesh Clean Energy Transmission Investment Program - Tranche 3 Prepared by Himachal Pradesh Power Transmission Corporation Limited (HPPTCL) for the Asian Development Bank. This social monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Recd. 29.4.21 SFG Log: 4616 January 2020 to June 2020 Social Monitoring Report HIMACHAL PRADESH POWER TRANSMISSION CORPORATION LTD. (A STATE GOVERNMENT UNDERTAKING) Semi-annual Social Monitoring Report Loan: 3733 IND April 2021 IND: Himachal Pradesh Clean Energy Transmission Investment Program - Tranche 3 Reporting Period: January 2020 to June 2020 Prepared by: Himachal Pradesh Power Transmission Corporation Ltd (A State Government Undertaking) for Asian Development Bank. Table of Contents 1. Introduction and Project Description ................................................................................................................ 1 2. Project Components .......................................................................................................................................... -

Cultivable Lands and Land Measurement in Early Assam Dr

ARTICLES / 1 Cultivable Lands and Land Measurement in Early Assam Dr. Nirode Boruah* The agrarian economy of a region does not simply speak of the rural agriculture based economy, it encompasses the areas like economic development and social progress and above all, the polity formation. This paper is an attempt to study the land measurement system prevailed in early Assam – a vital part of agrarian economy – which not only gives us an idea about the size of cultivable lands given in donation, pattern of agriculture, progress of agricultural expansion, agricultural production etc. In the study of agrarian economy in early Assam, the scholars like Nayanjot Lahiri,1 Chitrarekha Gupta,2 D. Nath,3 S. Chattopadhyaya,4 have already addressed some of the issues related to land system and agriculture. However, some of the important areas such as land measurement system prevailed in those days and the areas/size of the cultivated lands are yet to be explored. Except some incidental references, scholars have not gone thoroughly or dealt with these issues in organized form. Therefore, an attempt has been made to understand the unexplored areas of the broad theme, which may contribute an additional note to the study of the rural settlements and pattern of agriculture of early Assam. The main features of the rural environmental backdrop as reflected in the functional parts of the inscriptions of early Assam may be drawn in following outlines – (i) The rural settlements consisted of the arable land (kshetra), waste land (khila), land for cattle grazing which was located at the outskirts (go-(pro) câra bhumi) and homestead (vastubhumi) etc. -

Indigenous Housing and Settlement Pattern of Patro (Laleng) Community in Sylhet Shubhajit Chowdhury, Kawshik Saha

International Journal of Engineering and Innovative Technology (IJEIT) Volume 2, Issue 6, December 2012 Indigenous Housing and Settlement Pattern of Patro (Laleng) Community in Sylhet Shubhajit Chowdhury, Kawshik Saha belongs to the Bodo sub-section of Bodo-Naga section under Abstract: Patro community is one of about fifty indigenous the Assam-Burmese group of the Tibeto-Burman branch of communities in Bangladesh. They live in Sylhet and their the Tibeto-Chinese family. (Chatterji, 1951:12-30) Patros are population is decreasing day by day. They have a distinct culture, therefore, the branches of the ethnic group named Boro. As historical background and lifestyle, which are manifested in their significant housing and settlement pattern. Though the economic the references indicate these people are migrated to Assam condition is so poor, their neighborhood and community life is from south-west china via Tibet and Bhutan in ancient times. strong. This article attempts to search for the pattern language They developed the north east part of India including north and archetype of their settlement pattern. Although there is no east part of Bangladesh. Though they believe, there is no research work on settlement pattern of this community, there are known historical background of Patros of sylhet except the some works on their socio-economic and socio-cultural condition. information that Raja Gour Gobinda, the last Hindu ruler of Moreover, this study tries to collect information from three Patro Sylhet was one of their tribes (Sultan, 1984: 3). But there is a villages in the deep forest near Sylhet Sadar. After analyzing these probability that most of the Rajas in Sylhet and Kachhar, information, it is expected that an archetype of the Indigenous housing and settlement pattern of Patro (Laleng) Community will contemporary to Gour Gobinda came from the new or partial be found.