Toni Morrison's the Bluest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Development of Female Identity in a Complex Racial and Social Framework in Toni Morrison's Novels: the Bluest Eye and Sula

Development Of Female Identity In A Complex Racial And Social Framework In Toni Morrison’s Novels: The Bluest Eye And Sula Edita Bratanović Faculty of Philology Univeristy of Belgrade Serbia Abstract. The Bluest Eye, Toni Morrison’s first published novel that saw the light of day in 1970, is a very controversial piece of work, discussing the sensitive and disturbing topics of incest, racism and physical and mental abuse. It shows what kind of irreparable consequences the racial stereotypes and prejudices may have when they impact the psychological development of a young girl. Sula, Morrison’s second novel that was published in 1973, tells the story of the strong and unusual friendship that influenced the development of two very contrasting female personalities. It illustrates the importance of sisterhood, of women sticking together through the darkest of times and how that might be the solution to overcoming the complex racial and social circumstances surrounding the lives of African Americans. In this paper I will attempt to analyse all the challenges that the women in these two novels had to face while trying to develop their identities. I will look into the complex racial and social framework that made their path to the development of identity difficult and eventually I will examine Morrison’s possible suggestions of how to prevent the racial and social prejudices from affecting the women’s lives in the future. Keywords: African Americans, discrimination, female development, racism, stereotypes. 1. Introduction 22 Toni Morrison, one of the most distinguished and award-winning American writers, originates from the North, but her grandfather, after having his farm taken away from him and having suffered great injustice by white people, moved the family. -

DISCUSSION of the NEW OPERA MARGARET GARNER at the NATIONAL CONSTITUTION CENTER As Part of the Members Only Constitution Culture Club Series

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACTS: Denise Venuti Free Ashley Berke Director of Public Relations Public Relations Coordinator 215.409.6636 215.409.6693 [email protected] [email protected] DISCUSSION OF THE NEW OPERA MARGARET GARNER AT THE NATIONAL CONSTITUTION CENTER As part of the members only Constitution Culture Club series PHILADELPHIA, PA (January 26, 2006) – Members of the National Constitution Center will have the chance to discuss the new American opera Margaret Garner on Thursday, February 16 from 6:00 p.m.-7:30 p.m. The opera, based on one of the most significant slave stories in pre- Civil War America, marks the debut collaboration of composer Richard Danielpour and Nobel Prize-winning author Toni Morrison, and stars renowned mezzo-soprano Denyce Graves in the title role. Admission is free, but the Culture Club is limited to National Constitution Center members only. Please call the membership line at 215.409.6767 to reserve your place. Margaret Garner, presented by the Opera Company of Philadelphia, tells the story of a runaway slave, who tragically made the decision to sacrifice her own children when facing recapture rather than see them returned to slavery. Her trial became the subject of national debate, addressing issues of constitutional law and human rights. Participants are expected to see the opera prior to attending the Culture Club meeting. The National Constitution Center obtained a 10% discount for Garner Culture Club participants. Please contact The Opera Company at 215.732.8400 or visit www.operaphilly.com for more information. The Culture Club is an exclusive offering for members of the National Constitution Center. -

THE THEME of the SHATTERED SELF in TONI MORRISON's The

THE THEME OF THE Shattered SELF IN TONI MORRISON’S THE BLUEST EYE AND A MERCY Manuela López Ramírez IES Alto Palancia de Segorbe, Castellón [email protected] 75 The splitting of the self is a familiar theme in Morrison’s fiction. All of her novels explore, to some extent, the shattered identity. Under traumatic circumstances, the individual may suffer a severe psychic disintegration. Morrison has shown interest in different states of dementia caused by trauma which, as Clifton Spargo asserts, “has come to function for many critics as a trope of access to more difficult histories, providing us with entry into a world inhabited by the victims of extraordinary social violence, those perspectives so often left out of rational, progressive narratives of history” (2002). In Morrison’s narratives, dissociated subjectivity, like Pecola’s in The Bluest Eye, is usually connected to slavery and its sequels and, as Linda Koolish observes, is frequently the consequence of the confrontation between the Blacks’ own definition of themselves and slavery’s misrepresentation of African Americans as subhumans (2001: 174). However, Morrison has also dealt with insanity caused by other emotionally scarring situations, such as war in Sula’s character, Shadrack, or as a result of the loss of your loved ones, sudden orphanhood, as in A Mercy’s Sorrow. In this paper I focus on Morrison’s especially dramatic depiction of the destruction of the female teenager’s self and her struggle for psychic wholeness in a hostile world. The adolescent’s fragile identity embodies, better than any other, the terrible ordeal that the marginal self has to cope with to become a true human being outside the Western discourse. -

Aurora Theatre Company Presents Toni Morrison's

PRESS RELEASE MEDIA CONTACT FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Dayna Kalakau 510.843.4042 x311 [email protected] AURORA THEATRE COMPANY PRESENTS TONI MORRISON’S THE BLUEST EYE ADAPTED BY LYDIA R. DIAMOND BERKELEY, CA (January 7, 2021) Aurora Theatre Company continues its 29th season with Toni Morrison’s THE BLUEST EYE, adapted by Lydia R. Diamond. Associate Artistic Director Dawn Monique Williams (Bull In A China Shop) directs this poignant drama about Black girlhood, the poisonous effects of racism, and the heartbreak of shame. THE BLUEST EYE will be presented as an audio drama, consistent with Aurora’s reimagined digital 2020/2021 season due to the COVID-19 health crisis. The audio drama opens April 9th, and will be available through Aurora’s new membership program, and also for individual release. “When Dawn introduced me to Lydia Diamond's adaptation of THE BLUEST EYE, I was blown away,” said Artistic Director Josh Costello. “Diamond has translated Toni Morrison's story with such a sharp ear for making a scene spring off the page. And Morrison's story, exposing the ways racism can be internalized, feels as important now as when the novel was first published. We can't present THE BLUEST EYE on our stage during the pandemic, but I am so pleased that Aurora has received special permission to present Lydia Diamond's adaptation as an audio drama. Dawn is assembling a remarkable cast of local actors—it's going to be a captivating production.” THE BLUEST EYE runs April 9 - May 21 (Opens: April 9). Pulitzer Prize Winner Toni Morrison's debut novel, The Bluest Eye (which turned fifty in 2020), comes to Aurora in a stunning adaptation by playwright Lydia R. -

Book Review of the Bluest Eye Written by Toni Morrison INTRODUCTION

Book Review of The Bluest Eye written by Toni Morrison Dana Paramita FACULTY OF HUMANITIES DIPONEGORO UNIVERSITY INTRODUCTION 1. Background of Writing The writer chooses The Bluest Eye because this novel is challenging to be reviewed. The controversial nature of the book, which deals with racism, incest, and child molestation, makes it being one of the most challenged books in America’s libraries – the ones people complain about or ask to be removed, according to The American Library Association (http://www.ew.com/article/2015/04/14/here-are-american-library-associations- 10-most-complained-about-books-2014). On the other hand, the story of The Bluest Eye is interesting because the story tells about an eleven year old African American girl who hates her own self due to her black skin. She prays for white skin and blue eyes because they will make her beautiful and allow her to see the world differently, the community will treat her better as well. The story is set in Lorain, Ohio, against the backdrop of America's Midwest during the years following the Great Depression.The Bluest Eye is Toni Morrison's first novel published in 1970. 2. Purposes of Writing First of all, the purpose of the writing is that the writer would like to give the readers a portrait to stop hating themselves for everything they are not, and start loving themselves for everything that they are. The writer assesses that Toni Morrison’ story line presented in the novel is eye-catching eventhough it experiences an abundance of controversy because of the novel's strong language 1 and sexually explicit content. -

Anger Led to 8 Boone Co. Lynchings

6A ❚ TUESDAY, MAY 1, 2018 ❚ THE ENQUIRER Anger led to 8 Boone Co. lynchings Mark Curnutte Cincinnati Enquirer USA TODAY NETWORK Geography and prevailing anger among former Confederate soldiers were major reasons Boone County was the site of eight lynchings of black men during the 1870s and 1880s. The lynchings occurred from 1876 through 1885, which one historian re-fers to as an “intense 10-year period.” “For the time period, we had a pre-carious location, 40 miles of river-front” with free states Indiana and Ohio to the west and north, said Hillary Delaney, local history services associate at the Boone County Public Library. “This county aggressively tried to keep slaves in the state.” After the Civil War, a band of Con-federate army veterans organized loosely in Walton at the Gaines Tavern, which still stands today on Old Nicholson Road. “A segment of the population was intent on keeping slaves in their place,” Delaney said. “The lynchings were driven by these people from the Walton-Verona area. They fed off each other. They got people out of jail or just found them on their own.” Four of the eight documented lynchings of black men in Boone County are commemorated on a monument in the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. Billed as the first of its kind, the memorial that opened last month names 4,400 known African-Americans lynched during a 70-year reign of racial terror beginning in 1877. The names are inscribed in a 6-foot, rust-colored steel monument that hangs vertically – like a body – from the ceiling in the open-air memorial. -

MARGARET GARNER a New American Opera in Two Acts

Richard Danielpour MARGARET GARNER A New American Opera in Two Acts Libretto by Toni Morrison Based on a true story First performance: Detroit Opera House, May 7, 2005 Opera Carolina performances: April 20, 22 & 23, 2006 North Carolina Blumenthal Performing Arts Center Stefan Lano, conductor Cynthia Stokes, stage director The Opera Carolina Chorus The Charlotte Contemporary Ensemble The Charlotte Symphony Orchestra The Characters Cast Margaret Garner, mezzo slave on the Gaines plantation Denyce Graves Robert Garner, bass baritone her husband Eric Greene Edward Gaines, baritone owner of the plantation Michael Mayes Cilla, soprano Margaret’s mother Angela Renee Simpson Casey, tenor foreman on the Gaines plantation Mark Pannuccio Caroline, soprano Edward Gaines’ daughter Inna Dukach George, baritone her fiancée Jonathan Boyd Auctioneer, tenor Dale Bryant First Judge , tenor Dale Bryant Second Judge, baritone Daniel Boye Third Judge, baritone Jeff Monette Slaves on the Gaines plantation, Townspeople The opera takes place in Kentucky and Ohio Between 1856 and 1861 1 MARGARET GARNER Act I, scene i: SLAVE CHORUS Kentucky, April 1856. …NO, NO. NO, NO MORE! NO, NO, NO! The opera begins in total darkness, without any sense (basses) PLEASE GOD, NO MORE! of location or time period. Out of the blackness, a large group of slaves gradually becomes visible. They are huddled together on an elevated platform in the MARGARET center of the stage. UNDER MY HEAD... CHORUS: “No More!” SLAVE CHORUS THE SLAVES (Slave Chorus, Margaret, Cilla, and Robert) … NO, NO, NO MORE! NO, NO MORE. NO, NO MORE. NO, NO, NO! NO MORE, NOT MORE. (basses) DEAR GOD, NO MORE! PLEASE, GOD, NO MORE. -

The Bluest Eye Is About the Tragic Life of a Young Black Girl in 1940S Ohio

"Highly recommended ... an altogether superb (and harrowing) world premiere stage adaptation." -Hedy Weiss, Chicago Sun-Times "Poignant, provocative.” -Backstage “Remarkable” -Chicago Sun-Times © The Dramatic Publishing Company “This is bittersweet, moving drama that preserves the vigor and the disquiet of Ms. Morrison’s novel ... for theatergoers of any age, it is not to be missed.” -The New York Sun “A powerful coming-of-age story that should be seen by all young girls.” -Chicagocritic.com AATE Distinguished Play Award winner Drama. Adapted by Lydia R. Diamond. From the novel by Toni Morrison. Cast: 2 to 3m., 6 to 10w. Nobel Prize-winning author Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye is about the tragic life of a young black girl in 1940s Ohio. Eleven-year- old Pecola Breedlove wants nothing more than to be loved by her family and schoolmates. Instead, she faces constant ridicule and abuse. She blames her dark skin and prays for blue eyes, sure that love will follow. With rich language and bold vision, this powerful adaptation of an American classic explores the crippling toll that a legacy of racism has taken on a community, a family, and an innocent girl. “Diamond’s sharp, wrenching, deeply humane adaptation ... helps us discover how an innocent like Pecola can be undone so thoroughly by a racist world that, if it sees her at all, does so only long enough to kick the pins out from under her.” (Chicago Reader) “A spare and haunting play ... The playwright displays a delicate touch that seems right for the theme spiraling through the piece: that of the invidious influence of a white-majority nation not yet mature enough to validate beauty in all its forms.” (Washington Post) Flexible staging. -

Identity, Race and Gender in Toni Morrison's the Bluest

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL INSTITUTO DE LETRAS Rosana Ruas Machado Gomes Identity, Race and Gender in Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye Porto Alegre 1º Semestre 2016 Rosana Ruas Machado Gomes Identity, Race and Gender in Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye Monografia apresentada ao Instituto de Letras da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul como requisito parcial para a conclusão do curso de Licenciatura em Letras – Língua Portuguesa e Literaturas de Língua Portuguesa, Língua Inglesa e Literaturas de Língua Inglesa. Orientadora: Profª Drª Marta Ramos Oliveira Porto Alegre 1º Semestre 2016 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In recognition of their endless encouragement and support, I would like to thank my family, friends and boyfriend. It was extremely nice of you to pretend I was not very annoying when talking constantly about this work. Thank you for listening to discoveries of amazing interviews with Toni Morrison, complaints about back pains caused by sitting and typing for too many hours in a row, and meltdowns about deadlines. I also thank you for simply being part of my life–you make all the difference because you make me happy and give me strength to go on. I would especially like to thank Mariana Petersen for somehow managing to be a friend and a mentor at the same time. You have helped me deal with academic doubts and bibliography sources, and I am not sure I would have been able to consider myself capable of studying literature if you had not showed up. Since North-American literature is now one of my passions, I am extremely grateful for your presence in my life. -

John Conklin • Speight Jenkins • Risë Stevens • Robert Ward John Conklin John Conklin Speight Jenkins Speight Jenkins Risë Stevens Risë Stevens

2011 NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS 1100 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20506-0001 John Conklin • Speight Jenkins • Risë Stevens • Robert Ward John Conklin John Conklin Speight Jenkins Speight Jenkins Risë Stevens Risë Stevens Robert Ward Robert Ward NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS 2011 John Conklin’s set design sketch for San Francisco Opera’s production of The Ring Cycle. Image courtesy of John Conklin ii 2011 NEA OPERA HONORS Contents 1 Welcome from the NEA Chairman 2 Greetings from NEA Director of Music and Opera 3 Greetings from OPERA America President/CEO 4 Opera in America by Patrick J. Smith 2011 NEA OPERA HONORS RECIPIENTS 12 John Conklin Scenic and Costume Designer 16 Speight Jenkins General Director 20 Risë Stevens Mezzo-soprano 24 Robert Ward Composer PREVIOUS NEA OPERA HONORS RECIPIENTS 2010 30 Martina Arroyo Soprano 32 David DiChiera General Director 34 Philip Glass Composer 36 Eve Queler Music Director 2009 38 John Adams Composer 40 Frank Corsaro Stage Director/Librettist 42 Marilyn Horne Mezzo-soprano 44 Lotfi Mansouri General Director 46 Julius Rudel Conductor 2008 48 Carlisle Floyd Composer/Librettist 50 Richard Gaddes General Director 52 James Levine Music Director/Conductor 54 Leontyne Price Soprano 56 NEA Support of Opera 59 Acknowledgments 60 Credits 2011 NEA OPERA HONORS iii iv 2011 NEA OPERA HONORS Welcome from the NEA Chairman ot long ago, opera was considered American opera exists thanks in no to reside within an ivory tower, the small part to this year’s honorees, each of mainstay of those with European whom has made the art form accessible to N tastes and a sizable bankroll. -

Dr. Everett Mccorvey— Founder & Music Director

Dr. Everett McCorvey— Founder & Music Director Everett McCorvey, is a native of Montgomery, Alabama. He received his degrees from the University of Alabama, including a Doctorate of Musical Arts. As a tenor soloist, Dr. McCorvey has performed in many venues, including the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., the Metropolitan Opera in New York, Aspen Music Festival in Colorado, Radio City Music Hall in New York and in England, Germany, Italy, Spain, Japan and the Czech and Slovak Republics. During the summers, Dr. McCorvey is on the artist faculty of the American Institute of Musical Study (AIMS) in Graz, Austria. Dr. McCorvey currently holds the rank of Professor of Voice and Director of Opera at the University of Kentucky in Lexington, KY. Sopranos Tenors Performers Sonya Gabrielle Baker Alfonse Anderson Tedrin Blair Lindsay, Angela Brown Andreas Kirtley Pianist Jeryl Cunningham Albert R. Lee Calesta Day James E. Lee, Jr. Everett McCorvey, Founder Alicia M. Helm Phumzile Sojola and Music Director Hope Koehler Ervy Whitaker, Jr. Ricky Little, Assistant Andrea Jones-Sojola John Wesley Wright Conductor Amira Hocker Young Peggy Stamps, Janinah Burnett Basses Dancer/Stage Director Keith Dean James E. Lee, Company Altos Lawrence Fortson Manager Claritha Buggs Earl Hazell Lisa Hornung Ricky Little Hope Koehler Tay Seals Sherry Warsh Kevin Thompson Bradley Williard Baritone Thomas R. Beard, Jr. Kenneth Overton Soloist Biographies Alfonse Anderson, Tenor Dr. Alfonse Anderson, Vocal Area Coordinator and Associate Professor of Voice at University of Nevada Las Vegas received his bachelor and master's degrees in music from Texas Southern University, and DMA in voice and pedagogy from the University of Arizona. -

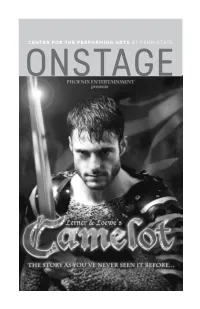

ONSTAGE Today’S Performance Is Sponsored By

CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS AT PENN STATE ONSTAGE Today’s performance is sponsored by with additional sponsorship support by COMMUNITY ADVISORY COUNCIL The Community Advisory Council is dedicated to strengthening the relationship between the Center for the Performing Arts and the community. Council members participate in a range of activities in support of this objective. Nancy VanLandingham, chair Bonnie Marshall Lam Hood, vice chair Pieter Ouwehand Melinda Stearns Judy Albrecht Lillian Upcraft William Asbury Pat Williams Lynn Sidehamer Brown Nina Woskob Philip Burlingame Deb Latta student representatives Eileen Leibowitz Brittany Banik Ellie Lewis Stephanie Corcino Christine Lichtig Jesse Scott Mary Ellen Litzinger CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS AT PENN STATE and Throne Games, LLC / Phoenix Entertainment present Book and Lyrics by Music by Alan Jay Lerner Frederick Loewe Original Production Directed and Staged by Moss Hart Based on The Once and Future King by T.H. White Scenic Design Costume Design Lighting Design Sound Design Kevin Depinet Paul Tazewell Mike Baldassari Craig Cassidy Musical Direction Musical Supervision/Add’l Orchestrations Casting Marshall Keating Steven M. Bishop Mark Minnick Director of Operations Marketing Director Technical Supervisor Lisa Mattia Aleman P.R./Phillip Aleman Scott Orlesky Production Stage Manager Company Manager J. Andrew Blevins Deborah Barrigan Directed by Michael McFadden CAMELOT is presented by arrangement with Tams-Witmark Music Library, Inc. 560 Lexington Avenue New York, NY 10022 EXCLUSIVE TOUR DIRECTION by THE ROAD COMPANY 165 West 46th Street, Suite 1101, New York, NY 10036, (212) 302-5200 www.theroadcompany.com www.camelottour.com www.phoenix-ent.com 7:30 p.m.