Anger Led to 8 Boone Co. Lynchings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DISCUSSION of the NEW OPERA MARGARET GARNER at the NATIONAL CONSTITUTION CENTER As Part of the Members Only Constitution Culture Club Series

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACTS: Denise Venuti Free Ashley Berke Director of Public Relations Public Relations Coordinator 215.409.6636 215.409.6693 [email protected] [email protected] DISCUSSION OF THE NEW OPERA MARGARET GARNER AT THE NATIONAL CONSTITUTION CENTER As part of the members only Constitution Culture Club series PHILADELPHIA, PA (January 26, 2006) – Members of the National Constitution Center will have the chance to discuss the new American opera Margaret Garner on Thursday, February 16 from 6:00 p.m.-7:30 p.m. The opera, based on one of the most significant slave stories in pre- Civil War America, marks the debut collaboration of composer Richard Danielpour and Nobel Prize-winning author Toni Morrison, and stars renowned mezzo-soprano Denyce Graves in the title role. Admission is free, but the Culture Club is limited to National Constitution Center members only. Please call the membership line at 215.409.6767 to reserve your place. Margaret Garner, presented by the Opera Company of Philadelphia, tells the story of a runaway slave, who tragically made the decision to sacrifice her own children when facing recapture rather than see them returned to slavery. Her trial became the subject of national debate, addressing issues of constitutional law and human rights. Participants are expected to see the opera prior to attending the Culture Club meeting. The National Constitution Center obtained a 10% discount for Garner Culture Club participants. Please contact The Opera Company at 215.732.8400 or visit www.operaphilly.com for more information. The Culture Club is an exclusive offering for members of the National Constitution Center. -

MARGARET GARNER a New American Opera in Two Acts

Richard Danielpour MARGARET GARNER A New American Opera in Two Acts Libretto by Toni Morrison Based on a true story First performance: Detroit Opera House, May 7, 2005 Opera Carolina performances: April 20, 22 & 23, 2006 North Carolina Blumenthal Performing Arts Center Stefan Lano, conductor Cynthia Stokes, stage director The Opera Carolina Chorus The Charlotte Contemporary Ensemble The Charlotte Symphony Orchestra The Characters Cast Margaret Garner, mezzo slave on the Gaines plantation Denyce Graves Robert Garner, bass baritone her husband Eric Greene Edward Gaines, baritone owner of the plantation Michael Mayes Cilla, soprano Margaret’s mother Angela Renee Simpson Casey, tenor foreman on the Gaines plantation Mark Pannuccio Caroline, soprano Edward Gaines’ daughter Inna Dukach George, baritone her fiancée Jonathan Boyd Auctioneer, tenor Dale Bryant First Judge , tenor Dale Bryant Second Judge, baritone Daniel Boye Third Judge, baritone Jeff Monette Slaves on the Gaines plantation, Townspeople The opera takes place in Kentucky and Ohio Between 1856 and 1861 1 MARGARET GARNER Act I, scene i: SLAVE CHORUS Kentucky, April 1856. …NO, NO. NO, NO MORE! NO, NO, NO! The opera begins in total darkness, without any sense (basses) PLEASE GOD, NO MORE! of location or time period. Out of the blackness, a large group of slaves gradually becomes visible. They are huddled together on an elevated platform in the MARGARET center of the stage. UNDER MY HEAD... CHORUS: “No More!” SLAVE CHORUS THE SLAVES (Slave Chorus, Margaret, Cilla, and Robert) … NO, NO, NO MORE! NO, NO MORE. NO, NO MORE. NO, NO, NO! NO MORE, NOT MORE. (basses) DEAR GOD, NO MORE! PLEASE, GOD, NO MORE. -

Toni Morrison's the Bluest

Bloom’s GUIDES Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye Biographical Sketch Raised in the North, Toni Morrison’s southern roots were deliberately severed by both her maternal and paternal grandparents. Her maternal grandfather, John Solomon Willis, had his inherited Alabama farm swindled from him by a predatory white man; as a consequence of this injustice, he moved his family first to Kentucky, where a less overt racism continued to make life intolerable, and then to Lorain, Ohio, a midwestern industrial center with employment possibilities that were drawing large numbers of migrating southern blacks. Her paternal grandparents also left their Georgia home in reaction to the hostile, racist culture that included lynchings and other oppressive acts. As a result, the South as a region did not exist as a benevolent inherited resource for Morrison while she was growing up; it became more of an estranged section of the country from which she had been helped to flee. As is evident in her novels, Morrison returned by a spiritually circuitous route to the strong southern traditions that would again be reinvigorated and re-experienced as life sustaining. The future Nobel literature laureate was born Chloe Ardelia Wofford at home in Lorain, Ohio, on February 18, 1931, the second child and daughter to George and Ella Ramah Willis Wofford. Two distinguishing experiences in her early years were, first, living with the sharply divided views of her parents about race (her father was actively disdainful of white people, her mother more focused on individual attitudes and behavior) and, second, beginning elementary school as the only child already able to read. -

John Conklin • Speight Jenkins • Risë Stevens • Robert Ward John Conklin John Conklin Speight Jenkins Speight Jenkins Risë Stevens Risë Stevens

2011 NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS 1100 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20506-0001 John Conklin • Speight Jenkins • Risë Stevens • Robert Ward John Conklin John Conklin Speight Jenkins Speight Jenkins Risë Stevens Risë Stevens Robert Ward Robert Ward NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS 2011 John Conklin’s set design sketch for San Francisco Opera’s production of The Ring Cycle. Image courtesy of John Conklin ii 2011 NEA OPERA HONORS Contents 1 Welcome from the NEA Chairman 2 Greetings from NEA Director of Music and Opera 3 Greetings from OPERA America President/CEO 4 Opera in America by Patrick J. Smith 2011 NEA OPERA HONORS RECIPIENTS 12 John Conklin Scenic and Costume Designer 16 Speight Jenkins General Director 20 Risë Stevens Mezzo-soprano 24 Robert Ward Composer PREVIOUS NEA OPERA HONORS RECIPIENTS 2010 30 Martina Arroyo Soprano 32 David DiChiera General Director 34 Philip Glass Composer 36 Eve Queler Music Director 2009 38 John Adams Composer 40 Frank Corsaro Stage Director/Librettist 42 Marilyn Horne Mezzo-soprano 44 Lotfi Mansouri General Director 46 Julius Rudel Conductor 2008 48 Carlisle Floyd Composer/Librettist 50 Richard Gaddes General Director 52 James Levine Music Director/Conductor 54 Leontyne Price Soprano 56 NEA Support of Opera 59 Acknowledgments 60 Credits 2011 NEA OPERA HONORS iii iv 2011 NEA OPERA HONORS Welcome from the NEA Chairman ot long ago, opera was considered American opera exists thanks in no to reside within an ivory tower, the small part to this year’s honorees, each of mainstay of those with European whom has made the art form accessible to N tastes and a sizable bankroll. -

Dr. Everett Mccorvey— Founder & Music Director

Dr. Everett McCorvey— Founder & Music Director Everett McCorvey, is a native of Montgomery, Alabama. He received his degrees from the University of Alabama, including a Doctorate of Musical Arts. As a tenor soloist, Dr. McCorvey has performed in many venues, including the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., the Metropolitan Opera in New York, Aspen Music Festival in Colorado, Radio City Music Hall in New York and in England, Germany, Italy, Spain, Japan and the Czech and Slovak Republics. During the summers, Dr. McCorvey is on the artist faculty of the American Institute of Musical Study (AIMS) in Graz, Austria. Dr. McCorvey currently holds the rank of Professor of Voice and Director of Opera at the University of Kentucky in Lexington, KY. Sopranos Tenors Performers Sonya Gabrielle Baker Alfonse Anderson Tedrin Blair Lindsay, Angela Brown Andreas Kirtley Pianist Jeryl Cunningham Albert R. Lee Calesta Day James E. Lee, Jr. Everett McCorvey, Founder Alicia M. Helm Phumzile Sojola and Music Director Hope Koehler Ervy Whitaker, Jr. Ricky Little, Assistant Andrea Jones-Sojola John Wesley Wright Conductor Amira Hocker Young Peggy Stamps, Janinah Burnett Basses Dancer/Stage Director Keith Dean James E. Lee, Company Altos Lawrence Fortson Manager Claritha Buggs Earl Hazell Lisa Hornung Ricky Little Hope Koehler Tay Seals Sherry Warsh Kevin Thompson Bradley Williard Baritone Thomas R. Beard, Jr. Kenneth Overton Soloist Biographies Alfonse Anderson, Tenor Dr. Alfonse Anderson, Vocal Area Coordinator and Associate Professor of Voice at University of Nevada Las Vegas received his bachelor and master's degrees in music from Texas Southern University, and DMA in voice and pedagogy from the University of Arizona. -

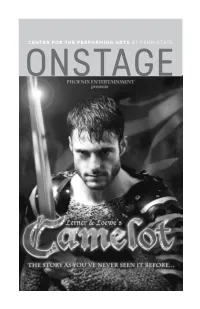

ONSTAGE Today’S Performance Is Sponsored By

CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS AT PENN STATE ONSTAGE Today’s performance is sponsored by with additional sponsorship support by COMMUNITY ADVISORY COUNCIL The Community Advisory Council is dedicated to strengthening the relationship between the Center for the Performing Arts and the community. Council members participate in a range of activities in support of this objective. Nancy VanLandingham, chair Bonnie Marshall Lam Hood, vice chair Pieter Ouwehand Melinda Stearns Judy Albrecht Lillian Upcraft William Asbury Pat Williams Lynn Sidehamer Brown Nina Woskob Philip Burlingame Deb Latta student representatives Eileen Leibowitz Brittany Banik Ellie Lewis Stephanie Corcino Christine Lichtig Jesse Scott Mary Ellen Litzinger CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS AT PENN STATE and Throne Games, LLC / Phoenix Entertainment present Book and Lyrics by Music by Alan Jay Lerner Frederick Loewe Original Production Directed and Staged by Moss Hart Based on The Once and Future King by T.H. White Scenic Design Costume Design Lighting Design Sound Design Kevin Depinet Paul Tazewell Mike Baldassari Craig Cassidy Musical Direction Musical Supervision/Add’l Orchestrations Casting Marshall Keating Steven M. Bishop Mark Minnick Director of Operations Marketing Director Technical Supervisor Lisa Mattia Aleman P.R./Phillip Aleman Scott Orlesky Production Stage Manager Company Manager J. Andrew Blevins Deborah Barrigan Directed by Michael McFadden CAMELOT is presented by arrangement with Tams-Witmark Music Library, Inc. 560 Lexington Avenue New York, NY 10022 EXCLUSIVE TOUR DIRECTION by THE ROAD COMPANY 165 West 46th Street, Suite 1101, New York, NY 10036, (212) 302-5200 www.theroadcompany.com www.camelottour.com www.phoenix-ent.com 7:30 p.m. -

The Double Consciousness of Cultural Pariahs—Fantasy, Trauma and Black Identity in Toni Morrison’S Tar Baby

EURAMERICA Vol. 36, No. 4 (December 2006), 551-590 © Institute of European and American Studies, Academia Sinica The Double Consciousness of Cultural Pariahs—Fantasy, Trauma and Black Identity in Toni Morrison’s Tar Baby Shao Yuh-chuan Department of English, National Taiwan Normal University E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This paper attempts to investigate the pathological condition of identity formation by reading Morrison’s novelistic reflection of the pathology of cultural pariahs in light of the psychoanalytic concepts of fantasy and trauma. By reflecting on the issue of black identity in Tar Baby through Slavoj Zizek’s Lacanian approach to ideology and the ethics of trauma proposed by Cathy Caruth and Petar Ramadonovic, this paper wishes to formulate a more sophisticated understanding of black identity and of the relationship between the subject and ideology. The discussion of the paper will first, by addressing the complex of “black skin, white self,” explore the alienation of black subjects in the white world and the identity crisis brought about by black embourgeoisement. The second part of the discussion will focus on the complexity of Morrison’s “double vision,” as embedded in the double consciousness of the protagonists, and on the pathological and ethical dimensions of double consciousness. The last part, then, will Received July 12, 2005; accepted August 28, 2006; last revised September 6, 2006 Proofreaders: Jeffrey Cuvilier, Jung Cheng-yu, Kaiju Chang, Min-Hsi Shieh 552 EURAMERICA tackle the intertwining relationship between black trauma and the reconstruction of black identity. The double consciousness of blacks as cultural pariahs, I would argue, can be taken as signifying the libidinal economy of the black subject and pointing to the double burden of the cultural pariah: this is a task of confronting the seduction of white culture and the legacy of black trauma and thus of confronting the real of black identity. -

History in Beloved Kristine Yohe

Margaret Garner, Rememory, and the Infinite Past: History in Beloved Kristine Yohe While Toni Morrison’s Beloved demonstrates a deep concern with the legacy of slavery in the United States, it also makes comprehensible for contemporary readers the dehumanizing personal experiences of enslaved individuals. As Morrison has said in multiple interviews, her intention in this novel was to create a “narrow and deep” internalized view of slavery instead of the wide, epic sweep that she had found to be more often depicted elsewhere. Beloved both draws on the historical record and creates an individualized past for her formerly enslaved characters, especially Sethe, Paul D, Baby Suggs, and Stamp Paid. These characters, in addition to Denver, who is born while Sethe is escaping, are simultaneously obsessed with and repelled by the horrors of their histories, haunted with pain while struggling to understand and make peace with their vivid “rememories.” In order to develop the depth of authenticity in Beloved, Morrison blends historical fact with imagination, thus resulting in a greater effect than either one could achieve separately. She simultaneously works to excavate hidden elements of American history for the culture at large, as well as for her specific characters, thus resulting in the potential of healing for all. Throughout her novels, Toni Morrison regularly focuses on history and its influence on the present. Whether this tendency manifests as characters stuck in the guilt of past mistakes, as we see in works ranging from The Bluest Eye (1970) to Home (2012) to God Help the Child (2015), or where family and communal history dominates, as in Song of Solomon (1976) and Paradise (1998), Morrison’s created world frequently looks back in time. -

Lift Every Voice

Governors State University OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship Center for Performing Arts Memorabilia Center for Performing Arts 2-19-2012 Lift veE ry Voice Center for Performing Arts Follow this and additional works at: http://opus.govst.edu/cpa_memorabilia Recommended Citation Center for Performing Arts, "Lift vE ery Voice" (2012). Center for Performing Arts Memorabilia. Book 266. http://opus.govst.edu/cpa_memorabilia/266 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Performing Arts at OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Center for Performing Arts Memorabilia by an authorized administrator of OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Governors State University CHBRfORPWORMIIMMS World-class singers performing opera classics in an intimate, on-stage setting This progtamJS-paffially supported by a grant from the Illinois Arts Council. Illinois ARTS 'Council The use of any recording device. either audit) or video, mid the taking of photographs, either with or without Hash, is strictly prohibited. February 19,2012 Lift Every Voice The 2012 An Operatic Celebration Season at GSU Center is of Black History Month sponsored by Soprano Kimberly Jones ^k Tenor Cornelius Johnson % First Midwest Bank PROGRAM Lift Every Voice and Sing arr. James Weldon Johnson Kimberly Jones and Cornelius Johnson Treemonisha Scott Joplin The Sacred Tree Ms. Jones Wrong Is Never Right Mr. Johnson Porgy and Bess George Gershwin Summertime Strawberry Woman Honey Man/Crabman It Ain't Necessarily So! Ms. Jones and Mr. Johnson i Margaret's Lullaby (from Margaret Garner) Richard Danielpour Ms. -

David Dichiera

DAVID DICHIERA 2013 Kresge Eminent Artist THE KRESGE EMINENT ARTIST AWARD HONORS AN EXCEPTIONAL ARTIST IN THE VISUAL, PEFORMING OR LITERARY ARTS FOR LIFELONG PROFESSIONAL ACHIEVEMENTS AND CONTRIBUTIONS TO METROPOLITAN DETROIT’S CULTURAL COMMUNITY. DAVID DICHIERA IS THE 2013 KRESGE EMINENT ARTIST. THIS MONOGRAPH COMMEMORATES HIS LIFE AND WORK. CONTENTS 3 Foreword 59 The Creation of “Margaret Garner” By Rip Rapson By Sue Levytsky President and CEO The Kresge Foundation 63 Other Voices: Tributes and Reflections 4 Artist’s Statement Betty Brooks Joanne Danto Heidi Ewing The Impresario Herman Frankel Denyce Graves 8 The Grand Vision of Bill Harris David DiChiera Kenny Leon By Sue Levytsky Naomi Long Madgett Nora Moroun 16 Timeline of a Lifetime Vivian R. Pickard Marc Scorca 18 History of Michigan Opera Theatre Bernard Uzan James G. Vella Overture to Opera Years: 1961-1971 Music Hall Years: 1972-1983 R. Jamison Williams, Jr. Fisher/Masonic Years: 1985-1995 Mayor Dave Bing Establishing a New Home: 1990-1995 Governor Rick Snyder The Detroit Opera House:1996 Senator Debbie Stabenow “Cyrano”: 2007 Senator Carol Levin Securing the Future By Timothy Paul Lentz, Ph.D. 75 Biography 24 Setting stories to song in MOTown 80 Musical Works 29 Michigan Opera Theatre Premieres Kresge Arts in Detroit 81 Our Congratulations 37 from Michelle Perron A Constellation of Stars Director, Kresge Arts in Detroit 38 The House Comes to Life: 82 A Note from Richard L. Rogers Facts and Figures President, College for Creative Studies 82 Kresge Arts in Detroit Advisory Council The Composer 41 On “Four Sonnets” 83 About the Award 47 Finding My Timing… 83 Past Eminent Artist Award Winners Opera is an extension of something that By David DiChiera is everywhere in the world – that is, 84 About The Kresge Foundation 51 Philadelphia’s “Cyranoˮ: A Review 84 The Kresge Foundation Board the combination of music and story. -

The Bluest Eye

The Bluest Eye (Questions) 1. Discuss the narrative structure of the novel. Why might Morrison have chosen to present the events in a non-chronological way? 2. Write an essay in which you discuss Morrison’s juxtaposing the primer’s Mother-Father-Dick-Jane sections with Claudia’s and the omniscient narrator’s sections. What is the relationship between these three differing narrative voices? 3. Discuss the significance of no marigolds blooming in the fall of 1941. 4. Compare Pecola’s character to Claudia’s. Which of these two characters is better able to reject white, middle-class America’s definitions of beauty? Support your answer with examples from the text. 5. Discuss the symbolism associated with Shirley Temple in the novel. What does she represent to Pecola? What might she represent to Maureen Peal? 6. Discuss Cholly’s dysfunctional childhood. What is his definition of what a family should be? Does knowing about his upbringing affect your reactions when he rapes Pecola? Why or why not? 7. How does Morrison present gender relations in the novel? Are men and women’s relationships generally portrayed positively or negatively? Support your answer with examples from the text. 8. Write an essay in which you compare Louis Junior’s and Soaphead Church’s treatments of Pecola. Is she treated worse by one of these characters than the other? If so, which one, and why? Is it significant that each relationship involves animals? 9. Discuss the mother-daughter relationships in the novel. 10. Does Morrison present any positive role models for Pecola and other girls like her? How might Morrison define what beauty is? Does she present any examples of such beauty in the novel? 11. -

A Review of Toni Morrison by Dr. Marilyn Mobley

Identity, Language and Power: Toni Morrison’s Perspective on the History of Enslavement Provost Scholars Program Thursday, October 15, 2015 Marilyn Sanders Mobley, PhD Vice President for Inclusion, Diversity & Equal Opportunity Professor of English www.case.edu/diversity/ A Context for Dialogue about Toni Morrison “Narrative is radical, creating us at the very moment it is being created.” --Toni Morrison, The Nobel Lecture, 1999 “This, then, is the end of his [or her] striving: to be a co-worker in the kingdom of culture…” --W.E.B. Du Bois, Souls of Black Folk, 1903 “Race can be defined externally (how others see us), internally (how we see ourselves), and expressively (how we present ourselves to others)…[To] think that people possess the traits they do because they are essential…is to commit what psychologists call a fundamental attribution error. --Scott E. Page, The Difference: How the Power of Diversity Creates Better Groups, Firm, Schools, and Societies, 2007 Goals and Objectives 1. To reflect on American history through Toni Morrison’s writing 2. To demonstrate how language shapes our worldview and the stories we tell about ourselves and others 3. To discuss the power of language to create change within ourselves and within our community Identity and History Identity Matters • Your Name • How You Identify Yourself • Some Unique Aspect of Your Identity • What You Value Most about Yourself History Matters • Slavery vs. Enslavement • Legal, Social, Psychological Perspectives • The Power of Love • Knowledge as Empowerment Who is Toni Morrison? “The vitality of language lies in its ability to limn the actual, imagined and possible lives of its speakers, readers, writers.