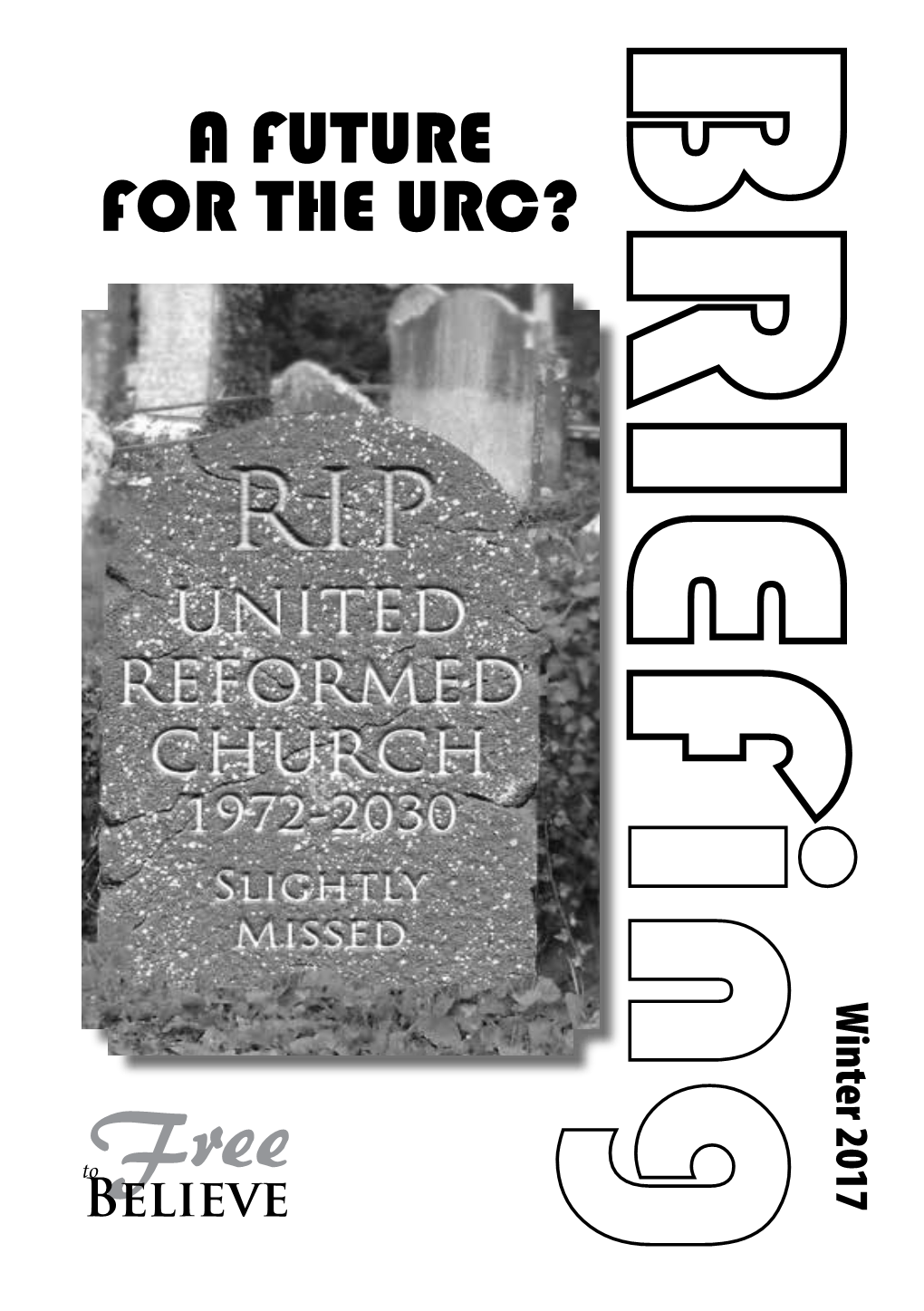

A Future for the Urc?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The United Reformed Church in Chappel

The United Reformed Church in Chappel We meet for worship The Chapel on Rose Green What we believe every Sunday at 6.30pm (Colchester Road - A1124) Holy Communion second Sunday each month We are a mainstream Christian Congregation. Baptisms, weddings and funerals by arrangement Our faith and our worship while rooted in Open to God with our Minister tradition, aims to be living and relevant to today’s Open to each other The Chapel premises are available for hire world with its varied issues and challenges. We contact the Secretary Open to the community believe in God revealed supremely in Jesus Christ; we treasure the inspired writings of the Bible and the work of the Holy Spirit in empowering Contacts Welcome . our lives as Christian people. We do not regularly Secretary recite creeds but we affirm broad statements of Anthony Percival The URC in Chappel is a place where you faith and church order, following the Christian tel: 01206 240442 will find a warm welcome and a heritage of liturgical calendar but not normally following e-mail: [email protected] Protestant Reformed Church worship. A place of set forms of worship. We respect the conscience friendship where tradition and new ideas mix, a of the individual believer in our search for God Minister place where all may find something to strengthen together. Local decisions about our Church are The Rev’d Kenneth M Forbes and refresh their lives made by the Elders, and at quarterly church tel: 01206 547920 RGP 7/2019 meetings by those who worship regularly. e-mail: [email protected] . -

Synod Hudsonville 1999

MINUTES of the Third Synod of the UNITED REFORMED CHURCHES in NORTH AMERICA held Tuesday, June 15 through Thursday, June 17, 1999 at Cornerstone United Reformed Church, Hudsonville, Michigan Contents Minutes page 1 Reports Report of the Calling Church page 29 Stated Clerk (preliminary) page 30 Stated Clerk page 31 Treasurers page 42 Ecumenical Relations and Church Unity page 48 Ecumenical Relations and Church Unity (Supplemental) page 78 Federative Structure Committee (United States and Canada) page 80 URCNA—OPC Study Committee page 90 Psalter Hymnal Committee page 92 Overtures and Appeals page 93 Ecumenical Observers page 105 MINUTES OF THE THIRD SYNOD of the UNITED REFORMED CHURCHES in NORTH AMERICA June 15-17, 1999 held at Cornerstone United Reformed Church Hudsonville, Michigan ARTICLE 1 The Chairman of the Council of the calling church, Cornerstone United Reformed Church of Hudsonville, Michigan, Mr. Henry Nuiver, calls for the singing of Psalter Hymnal Numbers 13, 298, and 308 . The Rev. Timothy Perkins, minister from Cornerstone United Reformed, reads from God’s Word and leads in opening prayer. ARTICLE 2 Roll call reveals the following delegates: Alto, MI Grace United Reformed Rev. Peter Adams Duane Sneller (6-15) Case Vierzen (6-16) Robert Tjapkes (6-17) Anaheim, CA Christ Reformed Rev. Kim Riddlebarger Dr. Michael Horton Aylmer, ON Bethel United Reformed Rev. Jerry Van Dyk Harry Van Gurp Balmoral, ON Covenant United Reformed Rev. Al Bezuyen Al Bruining Beecher, IL Faith United Reformed Rev. Todd Joling Dan Woldhuis Boise, ID Cloverdale United Reformed Lee De Heer Brockville/ Hulbert, ON Ebenezer Orthodox Reformed Rev John Roke Caledonia, MI Trinity United Reformed Rev. -

Download Complete Issue

THE JOURNAL of the UNITED REFORMED CHURCH HISTORY SOCIETY (incorporating the Congregational History Society, founded in 1899, and the Presbyterian Historical Society of England, founded in 1913). EDITOR: Dr. CLYDE BINFIELD, M.A. Volume 4 No. 3 October 1988 CONTENTS Editorial 169 Confessing the Faith in English Congregationalism by Alan P.F.Sell, M.A., B.D., Ph.D., F.S.A. 170 Zion, Hulme, Manchester: Portrait of a Church by Ian Sellers, M.A. M.Litt., Ph.D. 216 Reviews by Lilian Wildman, Mark Haydock, Edwin Welch 231 EDITORIAL This is the third successive edition ofthelournal to benefit from the generosity of an outside body. This time the debt is to the World Alliance of Reformed Churches. Professor Sell's paper was originally prepared for an Alliance consultation. Its contents are firmly in the traditions of the Journal and its Presbyterian and Congregational predecessors. Its style reaches back particularly to that of the Congregational Historical Society's earlier Transactions. As a summation of the confessional development of the larger part of the English tradition of what is now the United Reformed Church, Professor Sell's essay is self-evidently important. Is it too much to hope that it will be required reading for each student in a United Reformed college and each minister in a United Reformed pastorate, as well as for this Journal's constituency which goes beyond United Reformed boundaries? Dr. Sellers's paper is in suggestive counterpoint to Professor Sell's. It was delivered in May 1988 at Southport as the society's Assembly Lecture. To join these hardened contributors we welcome as reviewers Mrs. -

Download Complete Issue

THE JOURNAL of the UNITED REFORMED CHURCH HISTORY SOCIETY (incorporating the Congregational Historical Society, founded in 1899, and the Presbyterian Historical Society of England, founded in 1913). EDITOR: Dr. CLYDE BINFIELD, M.A. Volume 3 No.9 October 1986 CONTENTS Editorial 367 A Protestant Aesthetic? A Conversation with Donald Davie by Daniel T Jenkins, MA., B.D., D.D. 368 Nonconformist Poetics: A Response to Daniel Jenkins by Donald Davie, MA., Ph.D. 376 Abney and the Queen of Crime: A Note by Clyde Binjield, MA .. Ph.D. 386 William Baines in Leicester Gaol: A Note by David G. Cornick, B.D .. Ph.D .. A.K.C. 388 The Fellowship of Reconciliation: A Personal Retrospect by John Ferguson, MA .. B.D .. F.I.A.L.. F.R.S.A. 392 Reviews and Notes 400 EDITORIAL Of our contributors Dr. Jenkins is minister-in-charge at Paddington Chapel, Dr. Cornick is chaplain at Robinson College, Cambridge. Professor Ferguson was until recently President of the Selly Oak Colleges and Professor Davie is at Vanderbilt University, Tennessee. Dr. Jenkins, Dr. Cornick and Professor Ferguson are contributing articles for the first time. The conversation between Dr. Jenkins and Professor Davie, which moves from Protestant aesthetics to Nonconformist poetics, introduces a tone new to the Journal, to which pure historians might object. It is to be hoped that the conversation will continue, perhaps on architecture, or music, or indeed that vanishing art-form, the sermon. Professor Ferguson also introduces a new note: that of reminiscence. His stance is in a firm tradition, not too far removed from that of William Baines. -

A Handbook of Councils and Churches Profiles of Ecumenical Relationships

A HANDBOOK OF COUNCILS AND CHURCHES PROFILES OF ECUMENICAL RELATIONSHIPS World Council of Churches Table of Contents Foreword . vii Introduction . ix Part I Global World Council of Churches. 3 Member churches of the World Council of Churches (list). 6 Member churches by church family. 14 Member churches by region . 14 Global Christian Forum. 15 Christian World Communions . 17 Churches, Christian World Communions and Groupings of Churches . 20 Anglican churches . 20 Anglican consultative council . 21 Member churches and provinces of the Anglican Communion 22 Baptist churches . 23 Baptist World Alliance. 23 Member churches of the Baptist World Alliance . 24 The Catholic Church. 29 Disciples of Christ / Churches of Christ. 32 Disciples Ecumenical Consultative Council . 33 Member churches of the Disciples Ecumenical Consultative Council . 34 World Convention of Churches of Christ. 33 Evangelical churches. 34 World Evangelical Alliance . 35 National member fellowships of the World Evangelical Alliance 36 Friends (Quakers) . 39 Friends World Committee for Consultation . 40 Member yearly meetings of the Friends World Committee for Consultation . 40 Holiness churches . 41 Member churches of the Christian Holiness Partnership . 43 Lutheran churches . 43 Lutheran World Federation . 44 Member churches of the Lutheran World Federation. 45 International Lutheran Council . 45 Member churches of the International Lutheran Council. 48 Mennonite churches. 49 Mennonite World Conference . 50 Member churches of the Mennonite World Conference . 50 IV A HANDBOOK OF CHURCHES AND COUNCILS Methodist churches . 53 World Methodist Council . 53 Member churches of the World Methodist Coouncil . 54 Moravian churches . 56 Moravian Unity Board . 56 Member churches of the Moravian Unity Board . 57 Old-Catholic churches . 57 International Old-Catholic Bishops’ Conference . -

The United Reformed Church Archive 1936-2010

The United Reformed Church Archive 1936-2010 Catalogued by Jennifer Delves, Archivist and Records Manager, 2010-2011 1 The United Reformed Church Contents Page Introduction 2 Summary list 7 Detailed list 11 Appendix 1: General Assembly dates and locations 355 Appendix 2: Uniting Assemblies 356 Appendix 3: General Secretaries and Deputy General Secretaries 356 Appendix 4: General Assembly Moderators 357 2 The United Reformed Church (URC), 1936-2010 URC Introduction Introduction to the URC The United Reformed Church was created in 1972 by the uniting of the Presbyterian Church of England and the Congregational Church in England and Wales. The Reformed Association of Churches of Christ joined in 1981 and the Scottish Congregational Church in 2000. The URC is a Trinitarian church based in the United Kingdom. Its theological roots are Calvinist and its historical and organisational roots are in the Presbyterian, Congregational and Churches of Christ traditions. The Bible is taken to be its supreme authority together with certain historic statements of the United Reformed Church. The United Reformed Church takes the name ‘Reformed’ in recognition of its roots in the Genevan Reformation of the 16th Century. It has a commitment to continual reformation in order to be a church for today as summed up in the traditional motto, "Reformans Semper Reformandans.” The URC is part of the worldwide family of reformed churches, "The World Communion of Reformed Churches," which has a membership of over 80 million. The URC believes that all God’s people should be one and therefore seeks to work closely with Christians of all traditions and has united with a number of other churches. -

CEC Member Churches

Conference of European Churches MEMBER CHURCHES CEC Member Churches This publication is the result of an initiative of the Armenian Apostolic Church, produced for the benefit of CEC Member Churches, in collaboration with the CEC secretariat. CEC expresses its gratitude for all the work and contributions that have made this publication possible. Composed by: Archbishop Dr. Yeznik Petrosyan Hasmik Muradyan Dr. Marianna Apresyan Editors: Dr. Leslie Nathaniel Fr. Shahe Ananyan Original design concept: Yulyana Abrahamyan Design and artwork: Maxine Allison, Tick Tock Design Cover Photo: Albin Hillert/CEC 1 2 CEC MEMBER CHURCHES - EDITORIAL TEAM Archbishop Yeznik Petrosyan, Dr. of Theology (Athens University), is the General Secretary of the Bible Society of Armenia. Ecumenical activities: Programme of Theological Education of WCC, 1984-1988; Central Committee of CEC, 2002-2008; Co-Moderator of Churches in Dialogue of CEC, 2002-2008; Governing Board of CEC, 2013-2018. Hasmik Muradyan works in the Bible Society of Armenia as Translator and Paratext Administrator. Dr. Marianna Apresyan works in the Bible Society of Armenia as EDITORIAL TEAM EDITORIAL Children’s Ministry and Trauma Healing projects coordinator, as lecturer in the Gevorgyan Theological University and as the president of Christian Women Ecumenical Forum in Armenia. The Revd Canon Dr. Leslie Nathaniel is Chaplain of the Anglican Church of St Thomas Becket, Hamburg. Born in South India, he worked with the Archbishop of Canterbury from 2009-2016, initially as the Deputy Secretary for Ecumenical Affairs and European Secretary for the Church of England and later as the Archbishop of Canterbury’s International Ecumenical Secretary. He is the Moderator of the Assembly Planning Committee of the Novi Sad CEC Assembly and was the Moderator of the CEC Assembly Planning Committee in Budapest. -

MEMBERS 2021 Version: 22 March 2021

MEMBERS 2021 Version: 22 March 2021 Oikocredit (EDCS UA) is a cooperative society with 552 members to date. The membership has 5 different categories and is made up of: 239 Churches 233 Church-related institutions 43 Partners 23 Support associations 14 Other member Members are shown per continent and country in the overview. The following graph shows the number of members per region: 191 120 105 71 52 13 Western Africa and Asia, Australia South North America Central and Europe Middle East and the America Eastern Pacific Central Europe America and the Caribbean Each member has invested in Oikocredit, at least one share of EUR 200 (or other currencies). Every member has one vote at the AGM independent of the amount invested. English Church Church-related institution Partner Support association Other members Sonstige Deutsch Kirche Kirchliche Organisation Partner Förderkreis Mitglieder Organisation Français église Partenaire Association de soutien Autres membres confessionnelle Organización relacionada Español Iglesia Socio Asociación de apoyo Otros miembros con la Iglesia Kerkgerelateerde Nederlands Kerk Partner Steunvereniging Andere leden organisatie OIKOCREDIT MEMBERS 2020 1 Africa Angola Igreja Evangélica Congregacional en Angola Igreja Evangélica Reformada de Angola-IERA Missão Evangélica Pentecostal de Angola Botswana African Methodist Episcopal Church Botswana Christian Council Botswana Young Women's Christian Association Dutch Reformed Church in Botswana Etsha Multipurpose Co-operative Society United Congregational Church -

Directory United Reformed Churches North America

DIRECTORY of the UNITED REFORMED CHURCHES in NORTH AMERICA November 2008 UNITED REFORMED CHURCHES in NORTH AMERICA Directory Index Directory Index ....................................................................................2 Introduction.........................................................................................3 Functionary Addresses and Committees .............................................4 Abbreviations and Symbols Used ........................................................5 Listing of Churches by Province/State ..........................................6 to 9 Statistics – Grand Total by Classis......................................................10 Statistics by Classis: Classis Central U.S....................................................................11 Classis Eastern U.S. ..................................................................12 Classis Michigan.......................................................................13 Classis Pacific Northwest .........................................................14 Classis Southern Ontario .........................................................15 Classis Southwest U.S. .............................................................16 Classis Western Canada...........................................................17 Former Names of United Reformed Churches..........................18 to 21 Former United Reformed Congregations ..........................................21 Directory of Ministers...............................................................22 -

MC/15/99 Methodist Council Appointments, October 2015

MC/15/99 Methodist Council Appointments, October 2015 (Underlined names indicate new committee members. Reasoned statements as received are set out at the end of the committee listings.) PART I: COMMITTEES APPOINTED BY THE COUNCIL FOR 2015-16 (1) All We Can (Methodist Relief and Development Fund) Trustees (SO 245) Mr David Lewis (Chair), Mrs Sian Arulanantham, Ms Claire Boxall, Mr Paul Cornelius, Ms Ria Delves, Mr Andrew Dye, Mrs Karen Lawson, Mr Jim Marr (Vice Chair), Dr Richard Vautrey. Link person from Methodist Council: The Revd Graeme J Halls Link person from Irish World Development and Relief Committee: The Revd David Nixon (2) Authorisations Committee (SO 011) The Revds Andrew J Lunn (Chair), J Keith Burrow, Stephen J Lindridge, Samuel E McBratney, Janet E Preston, Andrew M Roberts, Deacon Andrew Carter (3) British Methodist-Roman Catholic Dialogue Commission The Revds Dr Neil G Richardson (Co-Chair), Dr David M Chapman (Co-Secretary), Marian J Jones, Dr Timothy S Macquiban, Ian S Rutherford, Neil A Stubbens, Peter G Sulston, Dr Stephen D Wigley; Mr David Bradwell (4) Candidates’ Appeals Committee (SO 326A) The Revds R Graham Carter (Chair), Christopher J Cheeseman, David S Cruise, Antony F McClelland (Retired Presbyters); the Revds Sylvester O Deigh, Dr David Dickinson, Doreen C Hare, Andrew J L Hollins, Vindra Maraj Ogden, Colin A Smith, Philip S Turner, Nicola Vidamour (Serving Presbyters); Deacons Kathleen Barrett, Gwynneth Bamford, Allyson Henry, Gwenllian R Knighton, Jane S Middleton, G Peter Ogle; Dr Stewart Barr, Mrs Stella Bristow, Mr David Hulse, Mrs Ann P Leck, Mrs Helen Martyn, Mr David E Morgan, Miss Ann Pardoe, Mrs Joyce Powell From April 2016: The Revd Sheila Foreman, The Revd Margaret P Jones, Deacon Andrew C Packer, Mr Terry Ayres (5) Cliff College Committee (SO 341(1)) The Revd Rachel D Deigh (Chair), the Revd Canon Yvonne Richmond (Vice Chair), the Revd Dr Christopher Blake (Principal), Mrs Lesley Barrick, Mr Neil Fell, the Revd Prof James Grayson, Mr Stephen Judd, a person nominated by the Network Committee (TBA). -

THE JOURNAL of the UNITED REFORMED CHURCH HISTORY SOCIETY CONTENTS

THE JOURNAL of the UNITED REFORMED CHURCH HISTORY SOCIETY (incorporating the Congregational Historical Society founded in 1899, the Presbyterian Historical Society of England, founded in 1913, and the Churches of Christ Historical Society, founded in 1979) EDITOR: PROFESSOR CLYDE BINFIELD, M.A., F.S.A. Volume 8 No 10 May 2012 CONTENTS Editorial ........................................................................... 596 A Century of Worship at Egremont by PeterS. Richards ...................................................... 599 "The Dust and Joy of Human Life": Geoffrey Hoyland and some Congregational Links by Nigel Lemon ............................................................ 610 Is Geoffrey also among the Theologians? Part II by Alan PF Sell ............................................................ 624 Review Article: Remembering Pennar Davies (1911-1996) by Robert Pope ............................................................ 640 Reviews by Jean Silvan Evans and Keith Forecast .............................. 646 596 EDITORIAL Historians have a love-hate relationship with anniversaries. Anniversaries provide fine opportunities for historians to parade 'their wares, demonstrate their skills and proselytise. They allow for lectures, conferences, and publications. They also allow for cultural, professional, and political propaganda, and this should be alien to the scepticism which is as much a part of the historian's composition as insatiable curiosity and a commitment to communicate the essence of what is being discovered about the past. No historian can find any anniversary wholly satisfactory. Historians from the Christian tradition of which the United Reformed Church is part are particularly conscious of the challenge which it is their responsibility to confront. They belong to a tradition for which time is a defining aspect. At each communion service they share in a commemoration. Their profession of history is an extension of this. The year 2012 offers two particular anniversaries. -

B: the Structure of the United Reformed Church

B: The Structure of the United Reformed Church 1.(1)(a) Members of the United Reformed Church associated in a locality for worship witness and service shall together comprise a Local Church. Since the proper functioning of the Local Church is so fundamental to the life of the United Reformed Church, where there is a number of small congregations in proximity to one another unable separately to provide leadership and resources for the work of the church, such congregations shall consult with the synod to formulate an acceptable scheme for joining together with a single membership, a common Church Meeting and elders’ meeting, representative of all the constituent congregations, and a shared ministry. 1.(1)(b) Where two or more Local Churches together, and in consultation with the synod, decide that their mission will be more effective if they share resources and ordained ministry, they may, with the approval of the synod, form an association known as a group of churches with a structured relationship and a constitution governing the way in which they relate to one another as to the sharing of both resources and the ordained ministry. Each church within the group shall retain its own identity, and its Church Meeting and elders’ meeting shall continue to exercise all their functions in relation to that church, save that, so long as the constitution shall so declare, decisions relating to the calling of a minister (see paragraph 2(1)(vii)) may be taken by a single group Church Meeting at which all the members of each of the constituent churches in the group shall be eligible to attend and vote.