History of Gavilan College by Leah Halper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

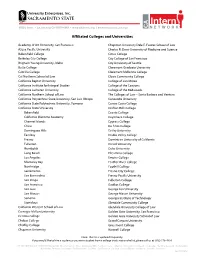

Affiliated Colleges and Universities

Affiliated Colleges and Universities Academy of Art University, San Francisco Chapman University Dale E. Fowler School of Law Azusa Pacific University Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science Bakersfield College Citrus College Berkeley City College City College of San Francisco Brigham Young University, Idaho City University of Seattle Butte College Claremont Graduate University Cabrillo College Claremont McKenna College Cal Northern School of Law Clovis Community College California Baptist University College of San Mateo California Institute for Integral Studies College of the Canyons California Lutheran University College of the Redwoods California Northern School of Law The Colleges of Law – Santa Barbara and Ventura California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo Concordia University California State Polytechnic University, Pomona Contra Costa College California State University Crafton Hills College Bakersfield Cuesta College California Maritime Academy Cuyamaca College Channel Islands Cypress College Chico De Anza College Dominguez Hills DeVry University East Bay Diablo Valley College Fresno Dominican University of California Fullerton Drexel University Humboldt Duke University Long Beach El Camino College Los Angeles Empire College Monterey Bay Feather River College Northridge Foothill College Sacramento Fresno City College San Bernardino Fresno Pacific University San Diego Fullerton College San Francisco Gavilan College San Jose George Fox University San Marcos George Mason University Sonoma Georgia Institute of Technology Stanislaus Glendale Community College California Western School of Law Glendale University College of Law Carnegie Mellon University Golden Gate University, San Francisco Cerritos College Golden Gate University School of Law Chabot College Grand Canyon University Chaffey College Grossmont College Chapman University Hartnell College Note: This list is updated frequently. -

Administration

GAVILAN COLLEGE CATALOG 2017-2019 Full-Time Faculty A DMINISTRATION Achterman, Douglas (2012) 408-848-4809 Library B.S., University of California, Berkeley; M.A., California State University, Dominguez Hills; If you wish to contact administrators or faculty members by MLIS, San Jose State University; Ph.D., University of North Texas email, the majority of addresses are as follows: First initial of fi rst name, followed by last [email protected] Agaliotis, Paul (2016) 408-695-0018 (i.e., contact Debra Amaro at [email protected]) Aviation A.S., Gavilan College Superintendent / President Dean, Kinesiology & Athletics Amaro, Debra (1999) 408-848-4841 Ron Hannon (2001) Kathleen Rose (2009, President since 2016) Allied Health B.A., State University of New York at Geneso; A.A., Gavilan College; B.S.N., M.S.N., San Jose State University M.Ed., Ed.D., University of Arizona B.A., M.A., San Jose State University Amirkhanian, Maria (2006) 408-848-4796 Vice President, Academic Affairs Associate Dean, Community Development & Grants Management Music Michele Bresso (2017) B.M., Komitas State Conservatory of Music, Yerevan, Armenia; Randy Brown (2007) B.A., University of the Pacifi c, Stockton; M.A., California State University, Fresno; M.S., Regis University; B.A., San Diego State University; Ph.D., Tchaikovsky State Conservatory of Music, Moscow, M.A., Ph.D., Fielding Graduate University M.S., University of California, Davis; Russia Ph.D., University of California, Davis Vice President, Student Services Andrade, Neal (2006) 408-846-4916 Kathleen Moberg (2014) Interim Dean, Accessible Education Center Head Baseball Coach, Kinesiology Instructor B.A., M.A., San Jose State University A.A., Gavilan College; Brooke Boeding (2015) B.S., Portland State University; Vice President, Administrative Services A.A., Copper Mountain College; M.A., Nova Southeastern University B.A., M.S., California State University, Fresno; Frederick E. -

Hispanic-Serving Institutions (Hsis): 2019-20

Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSIs): 2019-20 The mission of Excelencia in Education is to accelerate Latino student success in higher education. A critical group of institutions enrolling and graduating Latino students are Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSIs). Summary of the 2019-20 HSI List In the 1980s, leaders recognized a small set of institutions enrolled a large percentage of Latino students but had low levels of resources to educate these students. The classification of Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSIs) formally recognized these institutions for capacity-building and other support. HSIs are defined as accredited, degree-granting public or private nonprofit institutions of higher education with 25% or more total undergraduate Hispanic full-time equivalent (FTE) student enrollment.1 In 2019-20, 569 institutions met the enrollment definition of HSIs. HSIs represent 18% of colleges/universities and enroll 67% of Latino undergraduates. The list of institutions identified as HSIs in this analysis is not intended to designate eligibility for any specific program; rather, the list is meant to assist in considering and analyzing the institutions that meet the basic legislative definition of a Hispanic-Serving Institution. The following list of HSIs was created using data from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS).2 Location Sector State/Location # HSIs Sector # HSIs % HSIs California 175 Public, 2-year 235 41% Texas 100 Private not-for-profit, 4-year or above 169 30% Puerto Rico 64 Public, 4-year or above 150 26% -

NOW AVAILABLE Adobe® Creative Cloud Apps for Work-At-Home

NOW AVAILABLE Adobe® Creative Cloud Apps for Work-at-Home Attention Faculty and Staff: Get access to all of the Adobe® Creative Cloud Apps for just $19.99 per year when you purchase an annual membership through the CollegeBuys Work at Home program. Creative Cloud Apps for Work-at-Home includes the essential software previously available in the Adobe® Creative Suite®, with updates available instantly. Think of it as the upgrade to end all upgrades. This offer is available to faculty and staff at colleges participating in the Adobe Enterprise Term License Agreement (see list of eligible colleges on back) and powered by CollegeBuys, a program of the Foundation for California Community Colleges, the official non-profit supporting the California Community College system. $19.99 To purchase, visit www.shopcollegebuys.org. ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION Exclusive savings on software and more. ELIGIBLE COLLEGES Allan Hancock College Fresno City College Ohlone College Antelope Valley College Gavilan College Orange Coast College Barstow College Golden West College Palo Verde College Berkeley City College Grossmont College Palomar College Butte College Hartnell College Pasadena City College Cabrillo College Irvine Valley College Porterville College Canada College Los Angeles City College Reedley College Chabot College Los Angeles Harbor College Riverside Community College Chaffey College Los Angeles Mission College Sacramento City College Coastline Community College Los Angeles Pierce College San Bernardino Valley College of Marin Los Angeles Southwest College San -

Karl S. Pister Leadership Opportunity Program

12 Karl S. Pister Leadership Opportunity Program University of California, Santa Cruz Developing California’s Leaders Insert List Here Prestigious $20,000 scholarship • List your services or products here. to attend UCSC. The University of California, Santa Cruz, has a strong commitment to the future of • List your services or products here. California. The Karl S. Pister Leadership Opportunity Program has been established to enable community • List your services or products here. college transfer students to complete their undergraduate studies at UC Santa Cruz. The • List your services or products here. scholarship is for junior-level UC transfer-eligible students who: • List your services or products here. • Have shown exceptional achievement through academic and extracurricular • List your services or products here. accomplishments despite adverse socioeconomic conditions; • List your services or products here. • Have demonstrated an involvement in How to Apply at Foothill College activities that assist and improve the lives of • List your services or products here. Contact the Financial Aid Office to request an application for the Karl S. Pister Leadership others; • Exhibit outstanding leadership qualities that Opportunity Program scholarship. The application deadline is February 1, 2017. reflect the ideals of the Pister Leadership Opportunity Program; Apply for admission to UC Santa Cruz no later than January 3, 2017. Visit the Transfer Center • Because of financial need, would not for more information. otherwise be able to attend UC Santa Cruz. • Students on a non-immigrant visa (e.g., F-1, Apply for financial aid by submitting the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) or J-1, etc.) are not eligible for this award. -

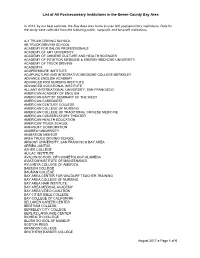

List of All Postsecondary Institutions in the Seven-County Bay Area

List of All Postsecondary Institutions in the Seven-County Bay Area In 2012, by our best estimate, the Bay Area was home to over 300 postsecondary institutions. Data for the study were collected from the following public, nonprofit, and for-profit institutions. A-1 TRUCK DRIVING SCHOOL AB TRUCK DRIVING SCHOOL ACADEMY FOR SALON PROFESSIONALS ACADEMY OF ART UNIVERSITY ACADEMY OF CHINESE CULTURE AND HEALTH SCIENCES ACADEMY OF INTUITION MEDICINE & ENERGY MEDICINE UNIVERSITY ACADEMY OF TRUCK DRIVING ACADEMYX ACUPRESSURE INSTITUTE ACUPUNCTURE AND INTEGRATIVE MEDICINE COLLEGE-BERKELEY ADVANCE ENGLISH ACADEMY ADVANCED PRO NURSING INSTITUTE ADVANCED VOCATIONAL INSTITUTE ALLIANT INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY, SAN FRANCISCO AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ENGLISH AMERICAN BAPTIST SEMINARY OF THE WEST AMERICAN CAREQUEST AMERICAN CENTURY COLLEGE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF NURSING AMERICAN COLLEGE OF TRADITIONAL CHINESE MEDICINE AMERICAN CONSERVATORY THEATER AMERICAN HEALTH EDUCATION AMERICAN TRUCK SCHOOL AMFASOFT CORPORATION ANDREW UNIVERSITY ANIMATION MENTOR AREA TRUCK DRIVING SCHOOL ARGOSY UNIVERSITY, SAN FRANCISCO BAY AREA ARRIBA JUNTOS ASHER COLLEGE AU LAC INSTITUTE AVALON SCHOOL OF COSMETOLOGY-ALAMEDA AVIATION INSTITUTE OF MAINTENANCE AYUVIDYA COLLEGE OF AMERICA BABSON COLLEGE BAUMAN COLLEGE BAY AREA CENTER FOR WALDORF TEACHER TRAINING BAY AREA COLLEGE OF NURSING BAY AREA HAIR INSTITUTE BAY AREA MEDICAL ACADEMY BAY AREA VIDEO COALITION BAY CITIES BIBLE COLLEGE BAY COLLEGE OF CALIFORNIA BELLAKEN CAREER CENTER BENTHAM COLLEGE BERKELEY CITY COLLEGE BERLITZ LANGUAGE CENTER -

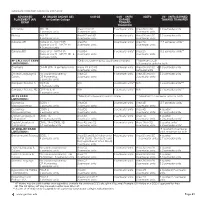

General Education and Transfer Programs

GAVILAN COLLEGE CATALOG 2017-2019 ADVANCED AA (MAJOR AND/OR GE) CSU GE CSU - UNITS IGETC UC - UNITS EARNED PLACEMENT (AP) for Gavilan College EARNED TOWARD TRANSFER EXAM TOWARD TRANSFER Art History ART 1A Area C1 or C2 6 semester units Area 3A or 3B 5.3 semester units 3 semester units 3 semester units 3 semester units Biology BIO 10 Area B2 and B3 6 semester units Area 5B and 5C 5.3 semester units 4 semester units 4 semester units 4 semester units Calculus AB Score of 3 – MATH 8B Area B4 3 semester units* Area 2A 2.7 semester units** Score of 4 or 5 – MATH 1A 3 semester units 3 semester units 4 Semester units Calculus BC Score of 3 – MATH 1A Area B4 6 semester units* Area 2A 5.3 semester units** Score of 4 or 5 – MATH 1B 4 3 semester units 3 semester units Semester units AP CALCULUS EXAM *Only one exam may be used toward transfer **Maximum credit LIMITATIONS: 5.3 semester units for both Chemistry CHEM 30A 4 semester units Areas B1 and B3 6 semester units Area 5A and 5C 4 5.3 semester units 4 semester units semester units Chinese Language & No course equivalency Area C2 6 semester units Area 3B and 6A 5.3 semester units Culture GE Humanities 3 semester units 3 semester units 3 semester units Computer Science A CSIS 45 N/A 3 semester units** N/A 1.3 semester units*** 3 Semester units Computer Science AB CSIS 45 & 46 N/A 6 semester units** N/A 2.7 semester units*** 6 semester units AP CS EXAM **Maximum one exam toward transfer ***Maximum 2.7 semester units for both LIMITATIONS: Economics - ECON 1 Area D2 3 semester units Area 4B 2.7 semester -

Northern Campuses

CalMHSA Student Mental Health Initiative Higher Ed Campus Program Partners Northern Campuses Southern Campuses Humboldt County (1) KEY Santa Barbara County (1) Humboldt State University (Arcata) UC Santa Barbara (SB) • University of California (10 UC) Butte County (2) • California State University (23 CSU) San Luis Obispo County (2) •UC San Francisco CSU Chico (Chico) • California Community College ( 23 CCC) CSU San Luis Obispo (SLO) • Butte College (Oroville) San Francisco State •Butte Cuesta College (SLO) Placer County (1) Kern County (1) •Sierra • Santiago Canyon Sierra College (Rocklin) CSU Bakersfield (Bakersfield) • Orange Consortia Sonoma County (2) •Santa Rosa Ventura County (1) Sonoma State University (Rohnert Park) CSU Channel Islands (Camarillo) Santa Rosa Junior College (SR) •Modesto Los Angeles County (17) Yolo County (1) •San Mateo •Columbia UC Los Angeles (LA) •Gavilan UC Davis (Davis) CSU Dominguez Hills (Carson) Sacramento County (1) CSU Long Beach (LB) •West Valley CSU Sacramento (Sacramento) •Fresno CSU Los Angeles (LA) California Community Colleges Chancellor's CSU Northridge (Northridge) Office (Sacramento) CSU Pomona (Pomona) San Francisco County (2) College of the Canyons (Santa Clarita) •Cuesta (SF) •SB Valley LA Harbor Consortia* (6 colleges) UC San Francisco • UC Los Angeles Pasadena College (Pasadena) San Francisco State University (SF) • CSU Los Angeles (Whittier) San Mateo (1) • College of the Canyon •Riverside City Rio Hondo College College of San Mateo (SM) • LA Harbor Consortia* •College of the Desert Santa -

Welcome to Gavilan College! Getting Started

Información en Español Table of Contents . página 32-35 Welcome to Gavilan College. 2 Administrators . 2 Board of Trustees. 2 Telephone Numbers. 3 Welcome to Gavilan College! Getting Started . 4 We’re rebuilding, from the ground Register for Spring Classes. 5 up. When you visit the Gavilan Fees. 6-7 College campus in Gilroy now, you’ll notice all of the construction Financial Aid. 7-10 activity underway. A new boiler Matriculation . 11-12 system has just gone in, and new Assessment. 11 infrastructure for electricity, gas, water, and communications will Orientation. 11 make the Gavilan college campus Counseling Services. 12 functional, comfortable, and High School Students. 12-15 “wired” . Once the infrastructure is complete, work will begin Transfer. 16-22 to renovate each building with Smart classrooms, better internal arrangements, air conditioning, and exterior lighting. Student Life. 23 After Measure E funds are spent, the campus will look much General Information. 24 the same as it does now -- from the outside. The buildings Policies and Procedures. 25-26 will retain their low-key, natural material exteriors and will remain the same size and shape. The insides, however, will Student Services. 27-28 have greater flexibility, functionality, and technology. It’s not Instructional Support and Labs. 29 a bad metaphor for education itself -- while it won’t change How to Use the Schedule. 31 you on the outside, it can give you the skills, knowledge and technological capability to compete in the global marketplace English as a Second Language (ESL). 32 and to be more effective at whatever you do. -

Adobe® Creative Cloud Apps

NEW EXCLUSIVE DISCOUNT FOR California Community College Students Adobe® Creative Cloud Apps ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION DIGITAL DOWNLOAD $169.99 NOW AVAILABLE FROM Adobe, the Adobe logo, Creative Cloud, the Creative Cloud logo, Dreamweaver, InDesign, Illustrator, and Photoshop are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Adobe Systems Incorporated in the United States and/or other countries. 07-2014 ADOBE ENTERPRISE TERM LICENSE AGREEMENT (ETLA) COLLEGES Adobe Enterprise Term License Agreement eligible colleges as of July 2014. For an updated list, visit collegebuys.org. Allan Hancock College Grossmont College Palomar College Antelope Valley College Hartnell College Pasadena City College Barstow College Irvine Valley College Porterville College Berkeley City College Lake Tahoe Community College Reedley College Butte College Laney College Riverside City College Cabrillo College Las Positas College Sacramento City College Cañada College Lassen College Saddleback College Chabot College Long Beach City College San Bernardino Valley College Chaffey College Los Angeles City College San Diego City College Citrus College Los Angeles Harbor College San Diego Continuing Education City College of San Francisco Los Angeles Mission College San Diego Mesa College Coastline Community College Los Angeles Pierce College San Diego Miramar College College of Marin Los Angeles Southwest College San Jose City College College of San Mateo Los Angeles Trade-Tech College Santa Ana College College of the Sequoias Los Angeles Valley College Santa Barbara City College College of the Siskiyous Mendocino College Santa Monica College Copper Mountain College Merced College Santa Rosa Junior College Cosumnes River College MiraCosta College Santiago Canyon College Crafton Hills College Mission College Sierra College Cuesta College Monterey Peninsula College Skyline College Cuyamaca College Moorpark College Solano Community College De Anza College Moreno Valley College Southwestern College East Los Angeles College Mt. -

Chapter 9: College Personnel

CHAPTER 9: COLLEGE PERSONNEL Baker, Jack (1996) Brown, Bonnie (2005) Biological Science Chemistry B.S., University of California, Riverside B.S., Tuskegee Institute M.A., University of California, Davis M.S., San José State University Banerjee, Sravani (2001) Brown, Robert (2011) English Accounting B.A., St. Xaviers College B.S., California Polytechnic State University M.A., San José State University M.A., Santa Clara University Banh, Phuong (2000) Burnham, Cynthia (1991) English/ESL Mathematics/Enlace B.A., English, B.S., University of State of New York M.S., TESOL San Francisco State University M.A., University of California, Berkeley Barta, Melody (2008) Burke, Leticia Aide (2001) Accounting English as a Second Language B.A., San José State University B.A., University of California, Berkeley M.S.,Taxation, San José State University M.A., San José State University Batalha, Celso (2003) Burton, Mirella (2006) Physics/Astronomy Counseling/Enlace B.S./M.S., Pontificia Universidade Catolica, B.A., California State University, Chico Rio De Janeiro, Brazil M.S.W., California State University, Sacramento Ph.D., Observatorio Nacional, Ph.D., Colorado State University Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Carothers, Brad (1996) Bergholdt, Bradley W� (1989) Psychology FACUltY AND ADMINistratORS Automotive Technology B.S./M.A., Arizona State University A.S., Evergreen Valley College University of California, Berkeley, Teacher Carpio, Theresa (2000) Adamski, Maureen (2008) Training Counseling/FasTrack Nursing B.A., University of California, Santa Cruz B.S., Temple -

Area Map and College Listing

Member Senate and Map North South AREA A AREA B AREA C AREA D American River College Alameda, College of Allan Hancock College Barstow College Bakersfield College Berkeley City College Antelope Valley College Chaffey College Butte College Cabrillo College Canyons, College of the Coastline College Cerro Coso College Cañada College Cerritos College Copper Mountain College Clovis College Chabot College Citrus College Crafton Hills College Columbia College Contra Costa College Compton College Cuyamaca College Cosumnes River College Contra Costa CC District Cuesta College Cypress College Feather River College De Anza College East Los Angeles College Desert, College of the Folsom Lake College Diablo Valley College El Camino College Fullerton College Glendale College Fresno City College Evergreen Valley College Golden West College Los Angeles City College Lake Tahoe College Foothill College Grossmont College Los Angeles CC District Lassen College Foothill - De Anza CC District Imperial Valley College Los Angeles Harbor College Los Rios CC District Gavilan College Irvine Valley College Los Angeles Mission College Madera Community College Hartnell College Long Beach City College Los Angeles Pierce College Merced College Laney College MiraCosta College Los Angeles Southwest College Modesto Junior College Las Positas College Moreno Valley College Los Angeles Trade-Technical Porterville College Los Medanos College Mt. San Jacinto College College Redwoods, College of the Marin, College of Norco College Los Angeles Valley College Reedley College Mendocino