48. Plant Bugs David B

Total Page:16

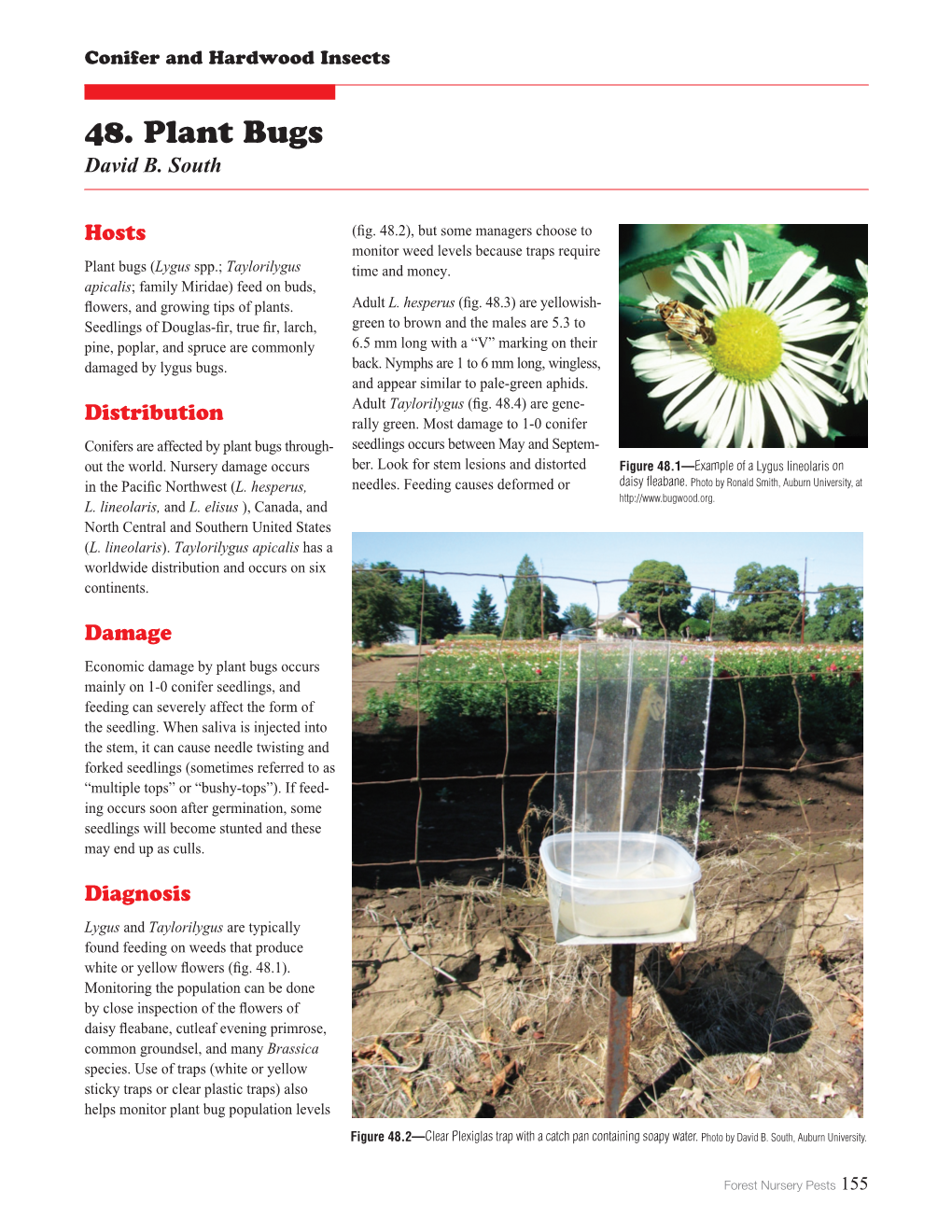

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Insecta Zeitschrift Für Entomologie Und Naturschutz

Insecta Zeitschrift für Entomologie und Naturschutz Heft 9/2004 Insecta Bundesfachausschuss Entomologie Zeitschrift für Entomologie und Naturschutz Heft 9/2004 Impressum © 2005 NABU – Naturschutzbund Deutschland e.V. Herausgeber: NABU-Bundesfachausschuss Entomologie Schriftleiter: Dr. JÜRGEN DECKERT Museum für Naturkunde der Humbolt-Universität zu Berlin Institut für Systematische Zoologie Invalidenstraße 43 10115 Berlin E-Mail: [email protected] Redaktion: Dr. JÜRGEN DECKERT, Berlin Dr. REINHARD GAEDIKE, Eberswalde JOACHIM SCHULZE, Berlin Verlag: NABU Postanschrift: NABU, 53223 Bonn Telefon: 0228.40 36-0 Telefax: 0228.40 36-200 E-Mail: [email protected] Internet: www.NABU.de Titelbild: Die Kastanienminiermotte Cameraria ohridella (Foto: J. DECKERT) siehe Beitrag ab Seite 9. Gesamtherstellung: Satz- und Druckprojekte TEXTART Verlag, ERIK PIECK, Postfach 42 03 11, 42403 Solingen; Wolfsfeld 12, 42659 Solingen, Telefon 0212.43343 E-Mail: [email protected] Insecta erscheint in etwa jährlichen Abständen ISSN 1431-9721 Insecta, Heft 9, 2004 Inhalt Vorwort . .5 SCHULZE, W. „Nachbar Natur – Insekten im Siedlungsbereich des Menschen“ Workshop des BFA Entomologie in Greifswald (11.-13. April 2003) . .7 HOFFMANN, H.-J. Insekten als Neozoen in der Stadt . .9 FLÜGEL, H.-J. Bienen in der Großstadt . .21 SPRICK, P. Zum vermeintlichen Nutzen von Insektenkillerlampen . .27 MARTSCHEI, T. Wanzen (Heteroptera) als Indikatoren des Lebensraumtyps Trockenheide in unterschiedlichen Altersphasen am Beispiel der „Retzower Heide“ (Brandenburg) . .35 MARTSCHEI, T., Checkliste der bis jetzt bekannten Wanzenarten H. D. ENGELMANN Mecklenburg-Vorpommerns . .49 DECKERT, J. Zum Vorkommen von Oxycareninae (Heteroptera, Lygaeidae) in Berlin und Brandenburg . .67 LEHMANN, U. Die Bedeutung alter Funddaten für die aktuelle Naturschutzpraxis, insbesondere für das FFH-Monitoring . -

Worldwide Literature of the Lygus Complex (Hemiptera, Miridae), 1900

Historic, Archive Document Do not assume content reflects current scientific knowledge, policies, or practices. Q I . United States^/ ^7 Department of Agriculture^j^gj^^ Worldwide Literature Agricultural Research Service of the Lygus Bibliographies and Literature of Agriculture Complex (Hemiptera: Number 30 Miridae), 1900-1980 cr CO CO ABSTRACT Graham, H. M. , A. A. Negm, and L. R. Ertle. 1984. Worldwide literature of the Lygus complex (Hemiptera: Miridae), 1900-1980. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Bibliographies and Literature of Agriculture No. 30, 205 p. This bibliography includes over 2,400 citations to the litera- ture published from 1900 to 1980 on members of the genus Lygus and closely related genera throughout the world. It is in- dexed by subject area, decade of publication, and the conti- nent where the research was conducted. KEYWORDS: Agnocoris , entomology, Hemiptera, insects, . Lygocoris , Lygus , Miridae, Orthops , plant pests, Taylorilygus Worldwide Literature of the Lygus Complex (Hemiptera: Miridae), 1900-1980 Compiled by H. M. Graham A. A. Negm L R. Ertle ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Henry Schreiber, soil scientist, Arid Land Ecosystems Improvement Laboratory, Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Tucson, Ariz., and Stefan Roth, student, University of Arizona, developed pro- grams for the computerized indexing of the bibliography. M. A. Morsi, Department of Plant Protection, Assiut University, Assiut, Egypt, translated the titles and summaries of many of the Russian articles; T. C. Yao, Department of Oriental Studies, University of Arizona, and C. M. Yin, Amherst, Mass., did some Chinese translations. Some of the references were provided by Robert Hedlund, entomologist, European Parasite Laboratory, ARS, USDA, Sevres, France; W. -

Annotated Checklist of the Plant Bug Tribe Mirini (Heteroptera: Miridae: Mirinae) Recorded on the Korean Peninsula, with Descriptions of Three New Species

EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ENTOMOLOGYENTOMOLOGY ISSN (online): 1802-8829 Eur. J. Entomol. 115: 467–492, 2018 http://www.eje.cz doi: 10.14411/eje.2018.048 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Annotated checklist of the plant bug tribe Mirini (Heteroptera: Miridae: Mirinae) recorded on the Korean Peninsula, with descriptions of three new species MINSUK OH 1, 2, TOMOHIDE YASUNAGA3, RAM KESHARI DUWAL4 and SEUNGHWAN LEE 1, 2, * 1 Laboratory of Insect Biosystematics, Department of Agricultural Biotechnology, Seoul National University, Seoul 08826, Korea; e-mail: [email protected] 2 Research Institute of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Seoul National University, Korea; e-mail: [email protected] 3 Research Associate, Division of Invertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY 10024, USA; e-mail: [email protected] 4 Visiting Scientists, Agriculture and Agri-food Canada, 960 Carling Avenue, Ottawa, Ontario, K1A, 0C6, Canada; e-mail: [email protected] Key words. Heteroptera, Miridae, Mirinae, Mirini, checklist, key, new species, new record, Korean Peninsula Abstract. An annotated checklist of the tribe Mirini (Miridae: Mirinae) recorded on the Korean peninsula is presented. A total of 113 species, including newly described and newly recorded species are recognized. Three new species, Apolygus hwasoonanus Oh, Yasunaga & Lee, sp. n., A. seonheulensis Oh, Yasunaga & Lee, sp. n. and Stenotus penniseticola Oh, Yasunaga & Lee, sp. n., are described. Eight species, Apolygus adustus (Jakovlev, 1876), Charagochilus (Charagochilus) longicornis Reuter, 1885, C. (C.) pallidicollis Zheng, 1990, Pinalitopsis rhodopotnia Yasunaga, Schwartz & Chérot, 2002, Philostephanus tibialis (Lu & Zheng, 1998), Rhabdomiris striatellus (Fabricius, 1794), Yamatolygus insulanus Yasunaga, 1992 and Y. pilosus Yasunaga, 1992 are re- ported for the fi rst time from the Korean peninsula. -

Chronobiology of Lygus Lineolaris (Heteroptera: Miridae): Implications for Rearing and Pest Management

Mississippi State University Scholars Junction Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1-1-2012 Chronobiology of Lygus Lineolaris (Heteroptera: Miridae): Implications for Rearing and Pest Management Sarah Rose Self Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/td Recommended Citation Self, Sarah Rose, "Chronobiology of Lygus Lineolaris (Heteroptera: Miridae): Implications for Rearing and Pest Management" (2012). Theses and Dissertations. 1059. https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/td/1059 This Dissertation - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Scholars Junction. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Junction. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Automated Template B: Created by James Nail 2011V2.01 Chronobiology of Lygus lineolaris (Heteroptera: Miridae): Implications for rearing and pest management By Sarah Rose Self A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Mississippi State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Agriculture and Life Science in the Department of Biochemistry, Molecular Biology, Entomology, and Plant Pathology Mississippi State, Mississippi August 2012 Chronobiology of Lygus lineolaris (Heteroptera: Miridae): Implications for rearing and pest management By Sarah Rose Self Approved: _________________________________ _________________________________ John C. Schneider Frank -

Synopsis of the Heteroptera Or True Bugs of the Galapagos Islands

Synopsis of the Heteroptera or True Bugs of the Galapagos Islands ' 4k. RICHARD C. JROESCHNE,RD SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO ZOOLOGY • NUMBER 407 SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of "diffusing knowledge" was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the Institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Folklife Studies Smithsonian Studies in Air and Space Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that report the research and collections of its various museums and bureaux or of professional colleagues in the world of science and scholarship. The publications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institutions throughout the world. Papers or monographs submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Press, subject to its own review for format and style, only through departments of the various Smithsonian museums or bureaux, where the manuscripts are given substantive review. -

Heteroptera: Miridae: Cylapinae)

Zootaxa 1153: 63–68 (2006) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA 1153 Copyright © 2006 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) A new Fulvius species from Azores Islands (Heteroptera: Miridae: Cylapinae) CHÉROT FRÉDÉRIC1*, RIBES JORDI2 & GORCZYCA JACEK3 1Free University of Brussels, Systematic and Animal Ecology, Department of Population Biology, C.P. 160/13, av. F. D. Roosevelt, 50, B - 1050 Brussels, Belgium. E-mail: [email protected] 2València 123-125, ent., 3a, E-08011 Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain. E-mail: [email protected] 3Silesian University, Department of Zoology, Bankowa 9, 40-007 Katowice, Poland. E-mail: [email protected] *Corresponding author. Abstract The new species Fulvius borgesi is described from Azores Islands. The male and female genital structures are illustrated. Key words: Heteroptera, Miridae, Cylapinae, Fulvinii, Fulvius, new species, Azores Islands Introduction Fulvius Stål, 1862 is the largest genus within the Cylapinae (Insecta: Heteroptera: Miridae), with upward of 60 species in the World (Gorczyca, 1997, 2000 ; Ferreira & Henry, 2002). Despite recent efforts to document the species of the genus, various taxa - particularly from the New World - remain undescribed. Recently, our colleague P. A. V. Borges sent to the second author a small series of Fulvius sp. impossible to attribute to an already known species, from Terceira, Azores Islands. In the present work, we provide the description of both sexes of Fulvius borgesi n. sp. to accomodate these specimens. The Arthoropoda biodiversity of Azores was recently reviewed (Borges et al., 2005). Eighteen Miridae species, including two endemics and fifteen assumed native (J. Ribes & Borges in Borges et al., 2005: 192), in four subfamilies (Bryocorinae, Mirinae, Orthotylinae, and Phylinae), are listed from the archipelago. -

Terrestrial Arthropod Surveys on Pagan Island, Northern Marianas

Terrestrial Arthropod Surveys on Pagan Island, Northern Marianas Neal L. Evenhuis, Lucius G. Eldredge, Keith T. Arakaki, Darcy Oishi, Janis N. Garcia & William P. Haines Pacific Biological Survey, Bishop Museum, Honolulu, Hawaii 96817 Final Report November 2010 Prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Pacific Islands Fish & Wildlife Office Honolulu, Hawaii Evenhuis et al. — Pagan Island Arthropod Survey 2 BISHOP MUSEUM The State Museum of Natural and Cultural History 1525 Bernice Street Honolulu, Hawai’i 96817–2704, USA Copyright© 2010 Bishop Museum All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America Contribution No. 2010-015 to the Pacific Biological Survey Evenhuis et al. — Pagan Island Arthropod Survey 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ......................................................................................................... 5 Background ..................................................................................................................... 7 General History .............................................................................................................. 10 Previous Expeditions to Pagan Surveying Terrestrial Arthropods ................................ 12 Current Survey and List of Collecting Sites .................................................................. 18 Sampling Methods ......................................................................................................... 25 Survey Results .............................................................................................................. -

An Annotated Catalog of the Iranian Miridae (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Cimicomorpha)

Zootaxa 3845 (1): 001–101 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Monograph ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2014 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3845.1.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:C77D93A3-6AB3-4887-8BBB-ADC9C584FFEC ZOOTAXA 3845 An annotated catalog of the Iranian Miridae (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Cimicomorpha) HASSAN GHAHARI1 & FRÉDÉRIC CHÉROT2 1Department of Plant Protection, Shahre Rey Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran. E-mail: [email protected] 2DEMNA, DGO3, Service Public de Wallonie, Gembloux, Belgium, U. E. E-mail: [email protected] Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand Accepted by M. Malipatil: 15 May 2014; published: 30 Jul. 2014 HASSAN GHAHARI & FRÉDÉRIC CHÉROT An annotated catalog of the Iranian Miridae (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Cimicomorpha) (Zootaxa 3845) 101 pp.; 30 cm. 30 Jul. 2014 ISBN 978-1-77557-463-7 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-77557-464-4 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2014 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41-383 Auckland 1346 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ © 2014 Magnolia Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, transmitted or disseminated, in any form, or by any means, without prior written permission from the publisher, to whom all requests to reproduce copyright material should be directed in writing. This authorization does not extend to any other kind of copying, by any means, in any form, and for any purpose other than private research use. ISSN 1175-5326 (Print edition) ISSN 1175-5334 (Online edition) 2 · Zootaxa 3845 (1) © 2014 Magnolia Press GHAHARI & CHÉROT Table of contents Abstract . -

Surveying for Terrestrial Arthropods (Insects and Relatives) Occurring Within the Kahului Airport Environs, Maui, Hawai‘I: Synthesis Report

Surveying for Terrestrial Arthropods (Insects and Relatives) Occurring within the Kahului Airport Environs, Maui, Hawai‘i: Synthesis Report Prepared by Francis G. Howarth, David J. Preston, and Richard Pyle Honolulu, Hawaii January 2012 Surveying for Terrestrial Arthropods (Insects and Relatives) Occurring within the Kahului Airport Environs, Maui, Hawai‘i: Synthesis Report Francis G. Howarth, David J. Preston, and Richard Pyle Hawaii Biological Survey Bishop Museum Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96817 USA Prepared for EKNA Services Inc. 615 Pi‘ikoi Street, Suite 300 Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96814 and State of Hawaii, Department of Transportation, Airports Division Bishop Museum Technical Report 58 Honolulu, Hawaii January 2012 Bishop Museum Press 1525 Bernice Street Honolulu, Hawai‘i Copyright 2012 Bishop Museum All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America ISSN 1085-455X Contribution No. 2012 001 to the Hawaii Biological Survey COVER Adult male Hawaiian long-horned wood-borer, Plagithmysus kahului, on its host plant Chenopodium oahuense. This species is endemic to lowland Maui and was discovered during the arthropod surveys. Photograph by Forest and Kim Starr, Makawao, Maui. Used with permission. Hawaii Biological Report on Monitoring Arthropods within Kahului Airport Environs, Synthesis TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents …………….......................................................……………...........……………..…..….i. Executive Summary …….....................................................…………………...........……………..…..….1 Introduction ..................................................................………………………...........……………..…..….4 -

Aerial Trapping of Kleidocerys Trunculatus (Or K

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Greenwich Academic Literature Archive Greenwich Academic Literature Archive (GALA) – the University of Greenwich open access repository http://gala.gre.ac.uk __________________________________________________________________________________________ Citation for published version: Reynolds, Don R., Nau, Bernard S. and Chapman, Jason W. (2013) High-altitude migration of Heteroptera in Britain. European Journal of Entomology, 110 (3). pp. 483-492. ISSN 1210-5759 (Print), 1802-8829 (Online) (doi:10.14411/eje.2013.064) Publisher’s version available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.14411/eje.2013.064 __________________________________________________________________________________________ Please note that where the full text version provided on GALA is not the final published version, the version made available will be the most up-to-date full-text (post-print) version as provided by the author(s). Where possible, or if citing, it is recommended that the publisher’s (definitive) version be consulted to ensure any subsequent changes to the text are noted. Citation for this version held on GALA: Reynolds, Don R., Nau, Bernard S. and Chapman, Jason W. (2013) High-altitude migration of Heteroptera in Britain. London: Greenwich Academic Literature Archive. Available at: http://gala.gre.ac.uk/12196/ __________________________________________________________________________________________ Contact: [email protected] This is the Author's Accepted Manuscript version, uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Please note: this is the author’s version of a work that was accepted for publication in the EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ENTOMOLOGY and published 11 July 2013 by the Institute of Entomology (Czech Republic). Changes resulting from the publishing process, such as editing, structural formatting, and other quality control mechanisms may not be reflected in this document. -

Entomofauna Ansfelden/Austria; Download Unter

© Entomofauna Ansfelden/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Entomofauna ZEITSCHRIFT FÜR ENTOMOLOGIE Band 33, Heft 9: 81-92 ISSN 0250-4413 Ansfelden, 2. Januar 2012 A revised identification key to the Lygus-species in Iran (Hemiptera: Miridae) Mohammadreza LASHKARI & Reza HOSSEINI Abstract In plant bugs of miridae, species of Lygus with a worldwide distribution has significant morphological variations which make them difficult to correctly identify. Three species of genus Lygus, including Lygus rugulipennis POPPIUS 1911, Lygus pratensis pratensis (LINNAEUS 1758) and Lygus gemellatus gemellatus (HERRICH SCHÄFFER 1835) have been reported from The North, North West And North East Of Iran. An identification key to the adult of Iranian Lygus species based on the hair and punctuation of the corium and pronotum is provided. Results indicated that the size of hairs on corium can be used as an important parameter for identifying of three Lygus species. Key words: Hemiptera, Miridae, Lygus, key. Zusammenfassung Drei Arten der Gattung Lygus (Hemiptera: Miridae) sind aus den nördlichen Provinzen Irans bisher bekannt: Lygus rugulipennis POPPIUS 1911, Lygus pratensis pratensis (LINNAEUS 1758) and Lygus gemellatus gemellatus (HERRICH SCHÄFFER 1835). Ein vorgestellter illustrierter Bestimmungsschlüssel soll die sichere Identifizierung der morphologisch variablen Arten ermöglichen. 81 © Entomofauna Ansfelden/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Introduction Lygus species (Hemiptera: Miridae) are economically important group of insects in row- crop agro-ecosystems (SHRESTHA et al. 2007). This genus is comprised of 43 species worldwide (KELTON 1975) where three species have been recorded from the Northern parts of Iran. Taxonomy of this genus has been revised several time by KNIGHT 1917; CHINA 1941; SLATER 1950; LESTON 1952; KELTON 1955; WAGNER 1957 and CARVALHO et al. -

Heteroptera, Miridae), Ravageur Du Manguier `Ala R´Eunion Morguen Atiama

Bio´ecologie et diversit´eg´en´etiqued'Orthops palus (Heteroptera, Miridae), ravageur du manguier `aLa R´eunion Morguen Atiama To cite this version: Morguen Atiama. Bio´ecologieet diversit´eg´en´etique d'Orthops palus (Heteroptera, Miridae), ravageur du manguier `aLa R´eunion.Zoologie des invert´ebr´es.Universit´ede la R´eunion,2016. Fran¸cais. <NNT : 2016LARE0007>. <tel-01391431> HAL Id: tel-01391431 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01391431 Submitted on 3 Nov 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L'archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destin´eeau d´ep^otet `ala diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publi´esou non, lished or not. The documents may come from ´emanant des ´etablissements d'enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche fran¸caisou ´etrangers,des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou priv´es. UNIVERSITÉ DE LA RÉUNION Faculté des Sciences et Technologies Ecole Doctorale Sciences, Technologies et Santé (E.D.S.T.S-542) THÈSE Présentée à l’Université de La Réunion pour obtenir le DIPLÔME DE DOCTORAT Discipline : Biologie des populations et écologie UMR Peuplements Végétaux et Bioagresseurs en Milieu Tropical CIRAD - Université de La Réunion Bioécologie et diversité génétique d'Orthops palus (Heteroptera, Miridae), ravageur du manguier à La Réunion par Morguen ATIAMA Soutenue publiquement le 31 mars 2016 à l'IUT de Saint-Pierre, devant le jury composé de : Bernard REYNAUD, Professeur, PVBMT, Université de La Réunion Président Anne-Marie CORTESERO, Professeur, IGEPP, Université de Rennes 1 Rapportrice Alain RATNADASS, Chercheur, HORTSYS, CIRAD Rapporteur Karen McCOY, Directrice de recherche, MiVEGEC, IRD Examinatrice Encadrement de thèse Jean-Philippe DEGUINE, Chercheur, PVBMT, CIRAD Directeur "Je n'ai pas d'obligation plus pressante que celle d'être passionnement curieux" Albert Einstein "To remain indifferent to the challenges we face is indefensible.