Authorship, Pseudonymity, and Trademark Law Laura A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Naming Conventions NAFSA TX State Mtg

1 2 3 4 1. Transcription is a more phonetic interpretation, while transliteration represents the letters exactly 2. Why transcription instead of transliteration? • Some English vowel sounds don’t exist in the other language and vice‐versa • Some English consonant sounds don’t exist in the other language and vice‐versa • Some languages are not written with letters 3. What issues are related to transcription and transliteration? • Lack of consistent rules from some languages or varying sets of rules • Country variation in choice of rules • Country/regional variations in pronunciation • Same name may be transcribed differently even within the same family • More confusing when common or religious names cross over several countries with different scripts (i.e., Mohammad et al) 5 Dark green countries represent those countries where Arabic is the official language. Lighter green represents those countries in which Arabic is either one of several official languages or is a language of everyday usage. Middle East and Central Asia: • Kurdish and Turkmen in Iraq • Farsi (Persian) and Baluchi in Iran • Dari, Pashto and Uzbek in Afghanistan • Uyghur, Kazakh and Kyrgyz in northwest China South Asia: • Urdu, Punjabi, Sindhi, Kashmiri, and Baluchi in Pakistan • Urdu and Kashmiri in India Southeast Asia: • Malay in Burma • Used for religious purposes in Malaysia, Indonesia, southern Thailand, Singapore, and the Philippines Africa: • Bedawi or Beja in Sudan • Hausa in Nigeria • Tamazight and other Berber languages 6 The name Mohamed is an excellent example. The name is literally written as M‐H‐M‐D. However, vowels and pronunciation depend on the region. D and T are interchangeable depending on the region, and the middle “M” is sometimes repeated when transcribed. -

1 Introduction

1 Introduction I. THE PROBLEM OF ANONYMITY NONYMOUS WRITING IS both an old and a new phenomenon. Before the Renaissance most writing was anonymous; many of the Aearly poems in anthologies are ascribed to ‘ Anon ’ . The medieval auctor (the term from which the word ‘ author ’ derives) was generally little more than a scribe, transcribing earlier texts. The name of the writer was irrelevant to the readers of a text, so it was immaterial that generally he was anonymous. 1 The identifi cation or naming of authors has been associated with the development of printing, and then subsequently with the role of copyright in ascribing property rights to them and the birth of the Romantic Author as a heroic fi gure at the end of the eighteenth century. 2 But even then a high proportion of novels were anonymous; between 1770 and 1800 over 70 per cent of novels were published without a named author, and during the 1820s the proportion rose to nearly 80 per cent. 3 There has certainly been a marked decline in anonymous writing in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, though some notable writers in this period have always, or sometimes, used pseudonyms (see section IV of this chapter and chapter 2 , section II), among them George Orwell (the pseudonym of Eric Blair), Sylvia Plath and Doris Lessing. The Internet is responsible for the revival of anonymous writing and indeed for many of the problems now associated with it. Many blogs are written under a pseudonym, though often the identity of the author is well known, as with Paul Staines, the author of the Guido Fawkes political blog. -

Lapp 1 the Victorian Pseudonym and Female Agency Research Thesis

Lapp 1 The Victorian Pseudonym and Female Agency Research Thesis Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with research distinction in English in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University by Anna Lapp The Ohio State University April 2015 Project Advisor: Professor Robyn Warhol, Department of English Lapp 2 Chapter One: The History of the Pseudonym Anonymity disguises information. For authors, disguised or changed names shrouds their circumstance and background. Pseudonyms, or pen names, have been famously used to disguise one’s identity. The word’s origin—pseudṓnymon—means “false name”. The nom de plume allows authors to conduct themselves without judgment attached to their name. Due to an author’s sex, personal livelihood, privacy, or a combination of the three, the pen name achieves agency through its protection. To consider the overall protection of the pseudonym, I will break down the components of a novel’s voice. A text is written by a flesh-and-blood, or actual, author. Second, an implied author or omnipresent figure of agency is present throughout the text. Finally, the narrator relates the story to the readers. The pseudonym offers freedom for the actual author because the author becomes two-fold—the pseudonym and the real person, the implied author and the actual author. The pseudonym can take the place of the implied author by acting as the dominant force of the text without revealing the personal information of the flesh-and-blood author. Carmela Ciuraru, author of Nom de Plume: A (Secret) History of Pseudonyms, claims, “If the authorial persona is a construct, never wholly authentic (now matter how autobiographical the material), then the pseudonymous writer takes this notion to yet another level, inventing a construct of a construct” (xiii-xiv). -

Family Law Form 12.982(A), Petition for Change of Name (Adult) (02/18) Copies, and the Clerk Can Tell You the Amount of the Charges

INSTRUCTIONS FOR FLORIDA SUPREME COURT APPROVED FAMILY LAW FORM 12.982(a) PETITION FOR CHANGE OF NAME (ADULT) (02/18) When should this form be used? This form should be used when an adult wants the court to change his or her name. This form is not to be used in connection with a dissolution of marriage or for adoption of child(ren). If you want a change of name because of a dissolution of marriage or adoption of child(ren) that is not yet final, the change of name should be requested as part of that case. This form should be typed or printed in black ink and must be signed before a notary public or deputy clerk. You should file the original with the clerk of the circuit court in the county where you live and keep a copy for your records. What should I do next? Unless you are seeking to restore a former name, you must have fingerprints submitted for a state and national criminal records check. The fingerprints must be taken in a manner approved by the Department of Law Enforcement and must be submitted to the Department for a state and national criminal records check. You may not request a hearing on the petition until the clerk of court has received the results of your criminal history records check. The clerk of court can instruct you on the process for having the fingerprints taken and submitted, including information on law enforcement agencies or service providers authorized to submit fingerprints electronically to the Department of Law Enforcement. -

Why Do People Seek Anonymity on the Internet?

Why Do People Seek Anonymity on the Internet? Informing Policy and Design Ruogu Kang1, Stephanie Brown2, Sara Kiesler1 Human Computer Interaction Institute1 Department of Psychology2 Carnegie Mellon University 5000 Forbes Ave., Pittsburgh, PA 15213 [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT literature that exists mainly derives from studies of one or a In this research we set out to discover why and how people few online communities or activities (e.g., the study of seek anonymity in their online interactions. Our goal is to 4chan in [5]). We lack a full understanding of the real life inform policy and the design of future Internet architecture circumstances surrounding people’s experiences of seeking and applications. We interviewed 44 people from America, anonymity and their feelings about the tradeoffs between Asia, Europe, and Africa who had sought anonymity and anonymity and identifiability. A main purpose of the asked them about their experiences. A key finding of our research reported here was to learn more about how people research is the very large variation in interviewees’ past think about online anonymity and why they seek it. More experiences and life situations leading them to seek specifically, we wanted to capture a broad slice of user anonymity, and how they tried to achieve it. Our results activities and experiences from people who have actually suggest implications for the design of online communities, sought anonymity, to investigate their experiences, and to challenges for policy, and ways to improve anonymity tools understand their attitudes about anonymous and identified and educate users about the different routes and threats to communication. -

Freedom of Expression, Encryption, and Anonymity: Civil Society and Private Sector Perceptions

Freedom of Expression, Encryption, and Anonymity: Civil Society and Private Sector Perceptions Joint collaboration to inform the work of the UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression Research Team World Wide Web Foundation Renata Avila Centre for Internet and Human Rights at European University Viadrina Ben Wagner Thomas Behrndt Oficina Antivigilância at the Institute for Technology and Society - ITS Rio Joana Varon Lucas Teixeira Derechos Digitales Paz Peña Juan Carlos Lara 2 About the Research In order to swiftly provide regional input for the consultation of the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the protection and promotion of the right to opinion and expression, the World Wide Web Foundation1, in partnership with the Centre for Internet and Human Rights at European University Viadrina, Oficina Antivigilância2 at the Institute for Technology and Society - ITS Rio3 in Brazil, and Derechos Digitales4 in Latin America, have conducted collaborative research on the use of encryption and anonymity in digital communications. The main goal of this initiative was to collect cases to highlight regional peculiarities from Latin America and a few other countries from the Global South, while debating the relationships within encryption, anonymity, and freedom of expression. This research was supported by Bertha Foundation.5 The core of the research was based on two different surveys focused on two target groups. The first was a series of interviews among digital and human rights organizations as well as potential users of the technologies to determine the level of awareness about both the anonymity and encryption technologies, to collect perceptions about the importance of these technologies to protect freedom of expression, and to have a brief overview of the legal framework and corporate practices in their respective jurisdictions. -

Reference Guides for Registering Students with Non English Names

Getting It Right Reference Guides for Registering Students With Non-English Names Jason Greenberg Motamedi, Ph.D. Zafreen Jaffery, Ed.D. Allyson Hagen Education Northwest June 2016 U.S. Department of Education John B. King Jr., Secretary Institute of Education Sciences Ruth Neild, Deputy Director for Policy and Research Delegated Duties of the Director National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance Joy Lesnick, Acting Commissioner Amy Johnson, Action Editor OK-Choon Park, Project Officer REL 2016-158 The National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE) conducts unbiased large-scale evaluations of education programs and practices supported by federal funds; provides research-based technical assistance to educators and policymakers; and supports the synthesis and the widespread dissemination of the results of research and evaluation throughout the United States. JUNE 2016 This project has been funded at least in part with federal funds from the U.S. Department of Education under contract number ED‐IES‐12‐C‐0003. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Department of Education nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. REL Northwest, operated by Education Northwest, partners with practitioners and policymakers to strengthen data and research use. As one of 10 federally funded regional educational laboratories, we conduct research studies, provide training and technical assistance, and disseminate information. Our work focuses on regional challenges such as turning around low-performing schools, improving college and career readiness, and promoting equitable and excellent outcomes for all students. -

Brookings Africa Research Fellows Application

Foreign Policy Pre-Doctoral Research Fellowship Program Application How to Apply: Interested candidates should submit the following: • Application questionnaire and research project proposal; • One publication or writing sample of 10 pages or less (excerpts of larger works acceptable) in PDF format; • Official or unofficial transcript from graduate institution (course names, professor names, grades received) in PDF format; and • One email message containing all required application attachments is highly preferred, with “PreDoc Application – [Last Name, First Name]” in the subject line. • In addition, three confidential letters of recommendation must be submitted to Brookings directly by referees. Instructions are included at the bottom of this document. Application Deadlines: • Applicants must submit a complete application package to [email protected] no later than January 31, 2016 in order to be considered as a candidate. • Letters of reference must be submitted to [email protected] no later than February 15, 2016. Please Note: • Materials sent through regular postal service will not be accepted. • Incomplete applications and those received after the deadline will not be considered. - continued - 1 Personal Information Full Legal Name (as it appears on your passport):____________________________________________________ Preferred name (or nickname):______________________________________________________ Current position/title: _________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Names in Toni Morrison's Novels: Connections

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality or this reproduction is dependent upon the quaUty or the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely. event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A. Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml48106·1346 USA 313!761·4700 8001521·0600 .. -------------------- ----- Order Number 9520522 Names in Toni Morrison's novels: Connections Clayton, Jane Burris, Ph.D. The University of North Carolina at Greensboro, 1994 Copyright @1994 by Clayton, Jane Burris. -

The Anonymity Heuristic: How Surnames Stop Identifying People When They Become Trademarks

Volume 124 Issue 2 Winter 2019 The Anonymity Heuristic: How Surnames Stop Identifying People When They Become Trademarks Russell W. Jacobs Follow this and additional works at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlr Part of the Behavioral Economics Commons, Civil Law Commons, Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Economic Theory Commons, Intellectual Property Law Commons, Law and Economics Commons, Law and Psychology Commons, Legal Writing and Research Commons, Legislation Commons, Other Law Commons, Phonetics and Phonology Commons, Psychiatry and Psychology Commons, Psycholinguistics and Neurolinguistics Commons, and the Semantics and Pragmatics Commons Recommended Citation Russell W. Jacobs, The Anonymity Heuristic: How Surnames Stop Identifying People When They Become Trademarks, 124 DICK. L. REV. 319 (2020). Available at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlr/vol124/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Dickinson Law IDEAS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dickinson Law Review by an authorized editor of Dickinson Law IDEAS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. \\jciprod01\productn\D\DIK\124-2\DIK202.txt unknown Seq: 1 28-JAN-20 14:56 The Anonymity Heuristic: How Surnames Stop Identifying People When They Become Trademarks Russell Jacobs ABSTRACT This Article explores the following question central to trade- mark law: if a homograph has both a surname and a trademark interpretation will consumers consider those interpretations as intrinsically overlapping or the surname and trademark as com- pletely separate and unrelated words? While trademark jurispru- dence typically has approached this question from a legal perspective or with assumptions about consumer behavior, this Article builds on the Law and Behavioral Science approach to legal scholarship by drawing from the fields of psychology, lin- guistics, economics, anthropology, sociology, and marketing. -

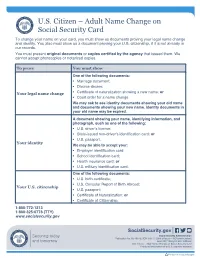

U.S. Citizen – Adult Name Change on Social Security Card to Change Your Name on Your Card, You Must Show Us Documents Proving Your Legal Name Change and Identity

U.S. Citizen – Adult Name Change on Social Security Card To change your name on your card, you must show us documents proving your legal name change and identity. You also must show us a document proving your U.S. citizenship, if it is not already in our records. You must present original documents or copies certified by the agency that issued them. We cannot accept photocopies or notarized copies. To prove You must show One of the following documents: • Marriage document; • Divorce decree; Your legal name change • Certificate of naturalization showing a new name; or • Court order for a name change. We may ask to see identity documents showing your old name and documents showing your new name. Identity documents in your old name may be expired. A document showing your name, identifying information, and photograph, such as one of the following: • U.S. driver’s license; • State-issued non-driver’s identification card; or • U.S. passport. Your identity We may be able to accept your: • Employer identification card; • School identification card; • Health insurance card; or • U.S. military identification card. One of the following documents: • U.S. birth certificate; • U.S. Consular Report of Birth Abroad; Your U.S. citizenship • U.S. passport; • Certificate of Naturalization; or • Certificate of Citizenship. 1-800-772-1213 1-800-325-0778 (TTY) www.socialsecurity.gov SocialSecurity.gov Social Security Administration Publication No. 05-10513 | ICN 470117 | Unit of Issue — HD (one hundred) June 2017 (Recycle prior editions) U.S. Citizen – Adult Name Change on Social Security Card Produced and published at U.S. -

Standardization of Parent Company Names - Style Guide

Standardization of Parent Company Names - Style Guide Reporters are required to enter the "Legal Name of United States Parent Company." EPA has defined U.S. parent company(s) as the highest- level U.S. company(s) with an ownership interest in the reporting entity as of December 31 of the year for which data are being reported. Please select you facility's parent company from the pick-list provided. A screen snap of the parent company page is shown below: >> Click this link to expand To improve the quality and utility of GHG data EPA has established guidelines for standardizing corporate parent names. As a first step EPA has established a pick list of existing corporate parents. The following 4 steps were taken standardize the names of on the pick list including: 1) Names were standardized and research was conducted to verify the name submitted was the highest-level of the company in the U. S. 2) For GHG reporters who also report to the Toxics Release Inventory (TRI), standardized names were sourced from the TRI parent company database. 3) For the sectors covered by the GHG reporting program only, parent companies were derived from internet research. 4) The List of Parent Companies with local government agencies (e. g., city, town, county government) was removed. A list of the parent company names provided on this pick list is available here. If your facility's parent company is not already on the parent company pick-list you will need to enter the parent company's name in e-GGRT. The following provides a "style guide" for parent company naming: Remember to: Eliminate all periods Enter & instead of AND Use "North America" instead of NA When reporting the Parent Company, use the terms displayed in the "Acronym" column of the table below: Acronym Definition CORP Corporation ASSOC Association CO Company DIV Division INC Incorp/Incorp./Incorporated LP Limited Partnership LTD Limited LLC Limited Liability Company PTNR Partnership USA United States of America US United States.