Nea, Once and Again

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Samford Israel Information

SAMFORD ISRAEL INFORMATION Dates May 17-29, 2016 Itinerary May 17 (Tue): Arrive Tel Aviv After our meet-up at Ben Gurion Airport in Tel Aviv, we take an easy bus ride to the coastal town of Netanya for a restful afternoon and dinner. Overnight: Seasons Hotel, Netanya May 18 (Wed): From Caesarea to the Sea of Galilee Our first day of exploring takes us to Caesarea Maritima, center of Rome’s rule over Israel and headquarters for Pontius Pilate. As we head north, we visit Mt. Carmel, the site of Elijah’s contest with the prophets of Baal. Next it is on to Megiddo, a store city during the days of King Solomon, for a look at Canaanite temples and the town’s ancient water system. From Megiddo, best known through its Greek name, Armageddon, we can imagine the scene envisioned by the author of Revelation. To close out the day, we ascend to the town of Nazareth, setting for the boyhood years of Jesus, before settling in at our hotel in the lakeside town of Tiberias. Overnight: Caesar Premier Hotel May 19 (Thu): North to the Golan Today we head north to explore the Upper Galilee. Our first stop is the important city of Hazor, famously conquered by Joshua during the time of the Conquest and again by Deborah during the time of the Judges. Leaving Hazor, we travel to ancient Israel’s northernmost city, Dan, where King Jeroboam provoked the prophets’ ire by installing a shrine housing a golden calf. We then visit the springs of nearby Banias, known in Jesus’ day as Caesarea Philippi, the location where Peter famously said, “You are the Christ, the son of the living God.” As we turn southward again, we visit the famous zealot outpost of Gamla before stopping at Kursi, the site where Jesus cast the demons into a herd of swine. -

By Jennifer M. Fogel a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy

A MODERN FAMILY: THE PERFORMANCE OF “FAMILY” AND FAMILIALISM IN CONTEMPORARY TELEVISION SERIES by Jennifer M. Fogel A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Amanda D. Lotz, Chair Professor Susan J. Douglas Professor Regina Morantz-Sanchez Associate Professor Bambi L. Haggins, Arizona State University © Jennifer M. Fogel 2012 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe my deepest gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee – Dr. Susan J. Douglas, Dr. Bambi L. Haggins, and Dr. Regina Morantz-Sanchez, who each contributed their time, expertise, encouragement, and comments throughout this entire process. These women who have mentored and guided me for a number of years have my utmost respect for the work they continue to contribute to our field. I owe my deepest gratitude to my advisor Dr. Amanda D. Lotz, who patiently refused to accept anything but my best work, motivated me to be a better teacher and academic, praised my successes, and will forever remain a friend and mentor. Without her constructive criticism, brainstorming sessions, and matching appreciation for good television, I would have been lost to the wolves of academia. One does not make a journey like this alone, and it would be remiss of me not to express my humble thanks to my parents and sister, without whom seven long and lonely years would not have passed by so quickly. They were both my inspiration and staunchest supporters. Without their tireless encouragement, laughter, and nurturing this dissertation would not have been possible. -

Ετς Θεος in Palestinian Inscriptions

ΕΤς θεος in Palestinian Inscriptions Leah Di Segni The acclamation Εἷς θεὸς, alone or in composition with various formulas, fre quently occurs in the East. In an extensive study, Ε. Peterson1 collected a large number of examples which he considered to be Christian, some as early as the late third century, from Syria (including Phoenicia, Palestine and Arabia) and Egypt, and concluded that Εἷς θεὸς was a typical Christian formula. Peterson’s conclusions were widely accepted and, not surprisingly, have become a self-ful filling prophecy, inasmuch as any inscription that contains this formula is auto matically classified as Christian, unless unequivocally proven otherwise. A more critical approach seems advisable, especially when dealing with Palestine, if for no other reason than the demographic diversity of this region, where Christians were still a minority at the beginning of the fifth century and possibly for some time later.2 While the material collected by Peterson from Egypt is indeed solidly Chris tian — mostly epitaphs with Christian symbols, many of them containing eccle siastic titles3 — the examples of Εἷς θεὸς from Syria include a sizable group of inscriptions that lack any positive identification. Of the dated material, a large majority of the unidentified Εἷς θεὸς inscriptions belong to the fourth century, whereas the texts identified as Christian by the addition of specific symbols and/or formulas come from the late fourth and fifth centuries. This seems to mean that in Syria the Εἷς θεὸς formula suffered a progressive Christianization, concomitant with the advance of Christianity in the province. In his collection of Syrian material, in fact, Prentice attributed the early specimens of Εἷς θεὸς to Ι Ε. -

49Th USA Film Festival Schedule of Events

HIGH FASHION HIGH FINANCE 49th Annual H I G H L I F E USA Film Festival April 24-28, 2019 Angelika Film Center Dallas Sienna Miller in American Woman “A R O L L E R C O A S T E R O F FABULOUSNESS AND FOLLY ” FROM THE DIRECTOR OF DIOR AND I H AL STON A F I L M B Y FRÉDERIC TCHENG prODUCeD THE ORCHARD CNN FILMS DOGWOOF TDOG preSeNT a FILM by FrÉDÉrIC TCHeNG IN aSSOCIaTION WITH pOSSIbILITy eNTerTaINMeNT SHarp HOUSe GLOSS “HaLSTON” by rOLaND baLLeSTer CO- DIreCTOr OF eDITeD MUSIC OrIGINaL SCrIpTeD prODUCerS STepHaNIe LeVy paUL DaLLaS prODUCer MICHaeL praLL pHOTOGrapHy CHrIS W. JOHNSON by ÈLIa GaSULL baLaDa FrÉDÉrIC TCHeNG SUperVISOr TraCy MCKNIGHT MUSIC by STaNLey CLarKe CINeMaTOGrapHy by aarON KOVaLCHIK exeCUTIVe prODUCerS aMy eNTeLIS COUrTNey SexTON aNNa GODaS OLI HarbOTTLe LeSLey FrOWICK IaN SHarp rebeCCa JOerIN-SHarp eMMa DUTTON LaWreNCe beNeNSON eLySe beNeNSON DOUGLaS SCHWaLbe LOUIS a. MarTaraNO CO-exeCUTIVe WrITTeN, prODUCeD prODUCerS ELSA PERETTI HARVEY REESE MAGNUS ANDERSSON RAJA SETHURAMAN FeaTUrING TaVI GeVINSON aND DIreCTeD by FrÉDÉrIC TCHeNG Fest Tix On@HALSTONFILM WWW.HALSTON.SaleFILM 4 /10 IMAGE © STAN SHAFFER Udo Kier The White Crow Ed Asner: Constance Towers in The Naked Kiss Constance Towers On Stage and Off Timothy Busfield Melissa Gilbert Jeff Daniels in Guest Artist Bryn Vale and Taylor Schilling in Family Denise Crosby Laura Steinel Traci Lords Frédéric Tcheng Ed Zwick Stephen Tobolowsky Bryn Vale Chris Roe Foster Wilson Kurt Jacobsen Josh Zuckerman Cheryl Allison Eli Powers Olicer Muñoz Wendy Davis in Christina Beck -

The Bedouin Population in the Negev

T The Since the establishment of the State of Israel, the Bedouins h in the Negev have rarely been included in the Israeli public e discourse, even though they comprise around one-fourth B Bedouin e of the Negev’s population. Recently, however, political, d o economic and social changes have raised public awareness u i of this population group, as have the efforts to resolve the n TThehe BBedouinedouin PPopulationopulation status of the unrecognized Bedouin villages in the Negev, P Population o primarily through the Goldberg and Prawer Committees. p u These changing trends have exposed major shortcomings l a in information, facts and figures regarding the Arab- t i iinn tthehe NNegevegev o Bedouins in the Negev. The objective of this publication n The Abraham Fund Initiatives is to fill in this missing information and to portray a i in the n Building a Shared Future for Israel’s comprehensive picture of this population group. t Jewish and Arab Citizens h The first section, written by Arik Rudnitzky, describes e The Abraham Fund Initiatives is a non- the social, demographic and economic characteristics of N Negev profit organization that has been working e Bedouin society in the Negev and compares these to the g since 1989 to promote coexistence and Jewish population and the general Arab population in e equality among Israel’s Jewish and Arab v Israel. citizens. Named for the common ancestor of both Jews and Arabs, The Abraham In the second section, Dr. Thabet Abu Ras discusses social Fund Initiatives advances a cohesive, and demographic attributes in the context of government secure and just Israeli society by policy toward the Bedouin population with respect to promoting policies based on innovative economics, politics, land and settlement, decisive rulings social models, and by conducting large- of the High Court of Justice concerning the Bedouins and scale social change initiatives, advocacy the new political awakening in Bedouin society. -

Burke Keynote Speaker Commencement, Page 21

Burke Keynote Speaker Commencement, Page 21 Classified, Page 26 Classified, ❖ ABC News Reporter Jennifer Donelan, a native of Fairfax County, gave the keynote address for the June 17 Lake Braddock Secondary Commencement. Donelan could not emphasize enough that this moment is a Real Estate, Page 16 Real Estate, ❖ milestone and a stepping off point to the future. Camps & Schools, Page 11 Camps & Schools, ❖ Faith, Page 23 ❖ Sports, Page 24 insideinside Requested in home 6-20-08 Time sensitive material. Attention Postmaster: U.S. Postage Word Out PRSRT STD PERMIT #322 Easton, MD On Repairs Koger Firm PAID News, Page 3 Auctioned Off News, Page 3 Photo By Louise Krafft/The Connection By Louise Krafft/The Photo www.connectionnewspapers.com www.ConnectionNewspapers.com June 19-25, 2008 Volume XXII, Number 25 Burke Connection ❖ June 19-25, 2008 ❖ 1 2 ❖ Burke Connection ❖ June 19-25, 2008 www.ConnectionNewspapers.com Burke Connection Editor Michael O’Connell News 703-917-6440 or [email protected] 2 Cases, 2 Courts, Same Day Groner gave Koger his Jeffrey Koger appears in Miranda rights en route to court on attempted capital Inova Fairfax Hospital. “You are under arrest for murder of police officer. attempted capital murder Koger Firm Sold of a police officer,” Groner told Koger, who was admit- Sheriff’s Photo Sheriff’s By Ken Moore ted to the hospital in criti- Troubled management firm The Connection cal condition. On Tuesday, June 17, auctioned in bankruptcy court. effrey Scott Koger held a shotgun Judge Penney S. Azcarate against his shoulder and pointed the certified the case to a By Nicholas M. -

FMC Travel Club

FMC Travel Club A subsidiary of Federated Mountain Clubs of New Zealand (Inc.) www.fmc.org.nz Club Convenor : John Dobbs Travel Smart Napier Civic Court, Dickens Street, Napier 4140 P : 06 8352222 F : 06 8354211 E : [email protected] In the footsteps of Jesus, the Patriarchs and Prophets 31 March to 30 April 2015, 31 days $6995 ex Tel Aviv. Based on a minimum group of 7 participants, and subject to currency fluctuations Costs calculated as at February 2014, so subject to revision in late 2014 Any payments by Visa or Mastercard adds $150 per person to the final A solo use room where this is possible adds $1000 to the final invoice Leader : Phillip Donnell Scene of divine revelations, home of the People of the Book, background of the marvels recorded in the Bible… lands sacred to Jew, Christian and Moslem. Visiting this region, retracing the footsteps of Jesus, the patriarchs and the prophets, is more than just a journey; it is a pilgrimage to the very source of faith… PRICE INCLUDES : All accommodations in Jordan, Sinai and Israel (twin shared where possible) All transport in Jordan, Sinai and Israel and connections between the 3 countries Most meals (all breakfasts, all dinners, lunches in Jordan and Sinai and special Shabbat dinner in Israel) The services of an experienced and knowledgeable Kiwi leader throughout Local leaders and full operational support in Jordan and Sinai National Parks passes, entrance fees (including World Heritage sites) and inclusions as shown in the daily itinerary PRICE DOES NOT INCLUDE : Flights to / from the region and arrival / departure airport transfers Travel insurance (mandatory) Lunches in Israel Personal incidentals e.g. -

A Theory of Regret This Page Intentionally Left Blank a THEORY of REGRET

a theory of regret This page intentionally left blank A THEORY OF REGRET Brian Price duke university press · Durham and London · 2017 © 2017 duke university press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ∞ Designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Scala by Copperline Books Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Price, Brian, [date] author. Title: A theory of regret / Brian Price. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Description based on print version record and cip data provided by publisher; resource not viewed. Identifiers: lccn 2017019892 (print) lccn 2017021773 (ebook) isbn 9780822372394 (ebook) isbn 9780822369363 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9780822369516 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: Regret. Classification: lcc bf575.r33 (ebook) | lcc bf575.r33 p75 2017 (print) | ddc 158—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017019892 Cover art: John Deakin, Photograph of Lucian Freud, 1964. © The Estate of Francis Bacon. All rights reserved. / dacs, London / ars, NY 2017 for alexander garcía düttmann This page intentionally left blank We do not see our hand in what happens, so we call certain events melancholy accidents when they are the inevitabilities of our projects (I, 75), and we call other events necessities because we will not change our minds. Stanley Cavell, The Senses of Walden I now regret very much that I did not yet have the courage (or immodesty?) at that time to permit myself a language of my very own for such personal views and acts of daring, la- bouring instead to express strange and new evaluations in Schopenhauerian and Kantian formulations, things which fundamentally ran counter to both the spirit and taste of Kant and Schopenhauer. -

How Sports Help to Elect Presidents, Run Campaigns and Promote Wars."

Abstract: Daniel Matamala In this thesis for his Master of Arts in Journalism from Columbia University, Chilean journalist Daniel Matamala explores the relationship between sports and politics, looking at what voters' favorite sports can tell us about their political leanings and how "POWER GAMES: How this can be and is used to great eect in election campaigns. He nds that -unlike soccer in Europe or Latin America which cuts across all social barriers- sports in the sports help to elect United States can be divided into "red" and "blue". During wartime or when a nation is under attack, sports can also be a powerful weapon Presidents, run campaigns for fuelling the patriotism that binds a nation together. And it can change the course of history. and promote wars." In a key part of his thesis, Matamala describes how a small investment in a struggling baseball team helped propel George W. Bush -then also with a struggling career- to the presidency of the United States. Politics and sports are, in other words, closely entwined, and often very powerfully so. Submitted in partial fulllment of the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism Copyright Daniel Matamala, 2012 DANIEL MATAMALA "POWER GAMES: How sports help to elect Presidents, run campaigns and promote wars." Submitted in partial fulfillment of the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism Copyright Daniel Matamala, 2012 Published by Columbia Global Centers | Latin America (Santiago) Santiago de Chile, August 2014 POWER GAMES: HOW SPORTS HELP TO ELECT PRESIDENTS, RUN CAMPAIGNS AND PROMOTE WARS INDEX INTRODUCTION. PLAYING POLITICS 3 CHAPTER 1. -

Caesarea-Ratzlaff201

The Plurality of Harbors at Caesarea: The Southern Anchorage in Late Antiquity Alexandra Ratzlaff, Ehud Galili, Paula Waiman-Barak & Assaf Yasur-Landau Journal of Maritime Archaeology ISSN 1557-2285 Volume 12 Number 2 J Mari Arch (2017) 12:125-146 DOI 10.1007/s11457-017-9173-z 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Springer Science+Business Media, LLC. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be self- archived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your article, please use the accepted manuscript version for posting on your own website. You may further deposit the accepted manuscript version in any repository, provided it is only made publicly available 12 months after official publication or later and provided acknowledgement is given to the original source of publication and a link is inserted to the published article on Springer's website. The link must be accompanied by the following text: "The final publication is available at link.springer.com”. 1 23 Author's personal copy J Mari Arch (2017) 12:125–146 DOI 10.1007/s11457-017-9173-z ORIGINAL PAPER The Plurality of Harbors at Caesarea: The Southern Anchorage in Late Antiquity 1 2 3 Alexandra Ratzlaff • Ehud Galili • Paula Waiman-Barak • Assaf Yasur-Landau1 Published online: 1 August 2017 Ó Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2017 Abstract The engineering marvel of Sebastos, or Portus Augusti as it was called in Late Antiquity (284–638 CE), dominated Caesarea’s harbor center along modern Israel’s central coast but it was only one part of a larger maritime complex. -

The Israel National Trail

Table of Contents The Israel National Trail ................................................................... 3 Preface ............................................................................................. 5 Dictionary & abbreviations ......................................................................................... 5 Get in shape first ...................................................................................................... 5 Water ...................................................................................................................... 6 Water used for irrigation ............................................................................................ 6 When to hike? .......................................................................................................... 6 When not to hike? ..................................................................................................... 6 How many kilometers (miles) to hike each day? ........................................................... 7 What is the direction of the hike? ................................................................................ 7 Hike and rest ........................................................................................................... 7 Insurance ................................................................................................................ 7 Weather .................................................................................................................. 8 National -

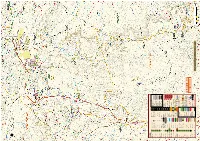

Trails Map Sde B Oker

פינת חי / גן חיות מחסום לרכב נחל איתן מקרא פינת חי / גן חיות מחסום לרכב נחל איתן עתיקותמקרא חוות סוסים שער כניסה / פתוח מאגר מים / אגם עתיקות חוות סוסים שער כניסה / פתוח מאגר מים / אגם מערה בית חולים שער סגור אגם עונתי/ מערה בית חולים Ü שער סגור אגם עונתי/ מערה בית חולים Ü שער סגור אשגטם ח עומנוצתיף/ לפרקים Ü שטח מוצף לפרקים אנדרטה בריכת מים ( 'דרכ י עפר לרכב (ר וחב> 2מ שטח מוצף לפרקים אנדרטה בריכת מים ( 'דרכ י עפר לרכב (ר וחב> 2מ אנדרטה בריכת מים ( 'דרכ י עפר לרכב (ר וחב> 2מ שמורת טבע / גן לאומי שמורת טבע / גן לאומי אתר פיקניק בור מים / באר דרך עפר שמורת טבע / גן לאומי אתר פיקניק בור מים / באר דרך עפר אתר פיקניק בור מים / באר דערביך רעה פלרכל רכב שטח אש עבירה לכל רכב שטח אש מבנה/אתר היסטורי מעיין עבירה לכל רכב שטח אש מבנה/אתר היסטורי מעיין מבנה/אתר היסטורי מעיין דרך עפר שטח חשוד במיקוש דרך עפר שטח חשוד במיקוש גן שעשועים מתקן שאיבה דערביך רעה פלררכב גבוה שטח חשוד במיקוש גן שעשועים מתקן שאיבה עבירה לרכב גבוה גן שעשועים מתקן שאיבה עבירה לרכב גבוה גבול בין לאומי גבול בין לאומי תחנת דלק אנטנה דרך עפר גבול בין לאומי תחנת דלק אנטנה דרך עפר תחנת דלק אנטנה דערביך רעה פלררכב 4*4 אתרים עבירה לרכב 4*4 אתרים בית כנסת עץ /קבוצת עצים Þ עבירה לרכב 4*4 (ארתארהי םרשימת אתרים) בית כנסת עץ /קבוצת עצים Þ (ראה רשימת אתרים) בית כנסת עץ /קבוצת עצים Þ דרך עפר (ראה רשימת אתרים) דרך עפר כנסייה רמזור גדרוךע הע /פ רמשנית אתר מעניין אתר כנסייה רמזור גרועה / משנית אתר מעניין אתר מסגד בניין עבירות קשה / אתר מומלץ מסגד בניין עבירות קשה / DD אתר מומלץ מסגד בניין עמבדיררוון ת תלקולשה / DD אתר מומלץ אתר מדרון תלול אתר קבר שיך מבנה ארעי / חקלאי / מדרון תלול קבר שיך מבנה