Calling Lake Report 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northwest Territories Territoires Du Nord-Ouest British Columbia

122° 121° 120° 119° 118° 117° 116° 115° 114° 113° 112° 111° 110° 109° n a Northwest Territories i d i Cr r eighton L. T e 126 erritoires du Nord-Oues Th t M urston L. h t n r a i u d o i Bea F tty L. r Hi l l s e on n 60° M 12 6 a r Bistcho Lake e i 12 h Thabach 4 d a Tsu Tue 196G t m a i 126 x r K'I Tue 196D i C Nare 196A e S )*+,-35 125 Charles M s Andre 123 e w Lake 225 e k Jack h Li Deze 196C f k is a Lake h Point 214 t 125 L a f r i L d e s v F Thebathi 196 n i 1 e B 24 l istcho R a l r 2 y e a a Tthe Jere Gh L Lake 2 2 aili 196B h 13 H . 124 1 C Tsu K'Adhe L s t Snake L. t Tue 196F o St.Agnes L. P 1 121 2 Tultue Lake Hokedhe Tue 196E 3 Conibear L. Collin Cornwall L 0 ll Lake 223 2 Lake 224 a 122 1 w n r o C 119 Robertson L. Colin Lake 121 59° 120 30th Mountains r Bas Caribou e e L 118 v ine i 120 R e v Burstall L. a 119 l Mer S 117 ryweather L. 119 Wood A 118 Buffalo Na Wylie L. m tional b e 116 Up P 118 r per Hay R ark of R iver 212 Canada iv e r Meander 117 5 River Amber Rive 1 Peace r 211 1 Point 222 117 M Wentzel L. -

The Camper's Guide to Alberta Parks

Discover Value Protect Enjoy The Camper’s Guide to Alberta Parks Front Photo: Lesser Slave Lake Provincial Park Back Photo: Aspen Beach Provincial Park Printed 2016 ISBN: 978–1–4601–2459–8 Welcome to the Camper’s Guide to Alberta’s Provincial Campgrounds Explore Alberta Provincial Parks and Recreation Areas Legend In this Guide we have included almost 200 automobile accessible campgrounds located Whether you like mountain biking, bird watching, sailing, relaxing on the beach or sitting in Alberta’s provincial parks and recreation areas. Many more details about these around the campfire, Alberta Parks have a variety of facilities and an infinite supply of Provincial Park campgrounds, as well as group camping, comfort camping and backcountry camping, memory making moments for you. It’s your choice – sweeping mountain vistas, clear Provincial Recreation Area can be found at albertaparks.ca. northern lakes, sunny prairie grasslands, cool shady parklands or swift rivers flowing through the boreal forest. Try a park you haven’t visited yet, or spend a week exploring Activities Amenities Our Vision: Alberta’s parks inspire people to discover, value, protect and enjoy the several parks in a region you’ve been wanting to learn about. Baseball Amphitheatre natural world and the benefits it provides for current and future generations. Beach Boat Launch Good Camping Neighbours Since the 1930s visitors have enjoyed Alberta’s provincial parks for picnicking, beach Camping Boat Rental and water fun, hiking, skiing and many other outdoor activities. Alberta Parks has 476 Part of the camping experience can be meeting new folks in your camping loop. -

Birds of Athabasca County

ABUNDANCE KEY HABITAT KEY Sp Su Au Wi Habitat Sp Su Au Wi Habitat A=always seen, high numbers (listed from most to least Sp Su Au Wi Habitat Falcons (Falconidae) Gulls and Terns (Laridae) BIRD IDENTIFICATION BOOKS C=common, usually seen, common) moderate numbers. Some L=lake Ducks (Anatidae) American Kestrel A A A C, F//, W// Franklin's Gull A C C R, L, W, S species are common only in R=river Wood Duck O L, W Merlin C C C F, L//, R, W, Bonaparte's Gull C C C L, R, W,F// Birds of Alberta. Chris Fisher and John Acorn. specific locations. W=wetland, ponds, bogs Gadwall C C C L, W C, S Edmonton: Lone Pine Publishing, 1998. U=uncommon, sometimes F=forest Ring-billed Gull A A A L//, R//, C, S seen, low numbers, or C=clearing American Wigeon C C C L, W, R Peregrine Falcon ● ● ● L//, F//, R// California Gull C C C L, W, C Field Guide to Alberta Birds. W. Bruce McGillivray irregularly high Sh=shrubby area Mallard A A A W, L, R Grouse (Phasianidae) Herring Gull U O U L, R, C, S and Glen P. Semenchuk. Edmonton: The O=occasionally seen, sporadic S=settlement Blue-winged Teal C C C W, L//,R// Gray Partridge U U U U C Federation of Alberta Naturalists, 1998. Italics ●=rare, seldom seen, //=edge of habitat Common Tern U U U L, W, R vagrant, unexpected, wanderer Cinnamon Teal ● ● L//, W// Ruffed Grouse C C C C F, Sh, W// Arctic Tern O O L The Sibley Guide to Birds. -

Calling Lake's Cardinal Seeks PC Nomination Locals to Decide On

A memorial round ance at Hobbema's Panee A iplex was a d by abo 400 last weekend. - da e attracted visitors from neigh. ng provinces as well as distant points like North Dakota, Oklahoma and New Mexico. Sponsors for the event were Ermineskin Chief Eddie Littlechild and his wife, and Eddie's sister, Theresa Crier. The gathering paid homage to their departed parents, two brothers and one sister. INSIDE THIS WEEK THIS WEEK `` t Fishing bms' DROPPIN' IN .ke, a Cardinal's art surprised Gro takes a new TAKES YOU 2 -er is reward turn as he re- TO HOBBEMA for his discovers See Pages 9 -20 cleverness in Metisism and his stamp design. roots. Calling Lake's Cardinal seeks PC nomination By Dianne Meili "I think I can manage as has occurred in the party, Cardinal explained Alberta. Since 1969 he has Cardinal finds time to very well. One of my Calling Lake area regarding he "believes in their party been working for the recharge and relax at his Mike Cardinal, a Metis strongest points is the employment rates. Since politics. Native people in government and has worked log home on the Calling from Calling Lake, is ability to communicate with he has been involved as a general across the north up through the ranks, Lake beach. He is married, entering the race for the all people. I can sit down social services advisor with are getting ready to join in holding a number of with two children, and Progressive says Conservative with trappers near Calling a job creation program to mainstream society and positions in the social and he likes to read political and nomination in the Athabasca Lake and the farmers in the provide an alternative to párticipate in economic economic development historical books in his spare Lac La Biche provincial Athabasca area." He also the welfare problems in that development and I feel the departments. -

Fever Master 2 August 11 2011

Rash of fires at JBG Reserve in Calling Lake Three residentialBy Bruce Thomas structures, three vehicles burn RCMP and fire investigators are trying to determine $ 00 if four fires which destroyed two unoccupied residential 1 structures and two vehicles early Saturday morning are linked to each other, plus a vehicle fire on September 18 and a house fire on September 20, also on the Jean Bap- tiste Gambler Reserve. There are concerns among residents of the Bigstone Cree Nation reserve and the community of Calling Lake that one or more arsonists are loose in the community and perhaps the next fire will involve an occupied build- ing. According to Athabasca RCMP, about 2 a.m. Septem- ber 26, police were notified that an unoccupied house on the Volume 16, Issue 38 Thursday, October 1, 2015 reserve was burning. When officers arrived to find the house fully engulfed in flames, they were informed by Calling Lake Fire Depart- ment that another structure was also on fire, as well as two Wabasca welcomes the World vehicles. as biggest amateur boxing event being held Saturday Three people were evacuated from a residence near A three-time world box- where the burning vehicles were parked. ing champ battling for a The second structure destroyed by flames Saturday place in the 2016 Olympics morning was a new residential duplex trailer operated by and former Olympian box- Bigstone Cree Nation Health Commission that was to be ers along with amateur used for professional people having to stay in the commu- champs from Alberta and nity to provide health services. -

Monitoring for Invasive Mussels in Alberta’S Irrigation Infrastructure: 2017 Report

Monitoring for Invasive Mussels in Alberta’s Irrigation Infrastructure: 2017 Report Alberta Agriculture and Forestry Water Quality Section Outlet of Sauder Reservoir January 2018 Introduction and Summary The Government of Alberta (GOA) is committed to protecting the province against aquatic invasive species (AIS), due to their negative ecological and economic effects. Invasive zebra mussels (Dreissena polymorpha) and quagga mussels (Dreissena bugensis) are of prominent concern, as these dreissenid mussels attach to any solid submerged surface and rapidly multiply due to their high reproductive rates. They are also very difficult to contain and eradicate once established. Additionally, they are spreading closer to Alberta’s borders. Alberta’s irrigation industry contributes $3.6 billion to the provincial gross domestic product (GDP). Specifically, it contributes about 20% of the provincial agri-food sector GDP on 4.7% of the province’s cultivated land base (Paterson Earth & Water Consulting 2015). Alberta’s irrigation industry includes thirteen irrigation districts that supply water to more than 570,000 ha of farmland through infrastructure valued at $3.6 billion. This infrastructure includes 57 irrigation reservoirs along with 3,491 km of canals and 4,102 km of pipelines (ARD 2014; AF 2017). The irrigation conveyance system provides water to irrigators, municipalities, industries, and wetlands, while the reservoirs support recreational activities such as boating and fishing and provide habitat to fish and waterfowl. Invasive mussels are a concern to the irrigation industry as infestations will have a significant negative effect on water infrastructure and conveyance works due to their ability to completely clog pipelines and damage raw-water treatment systems and intakes. -

Five Year General Development Plan

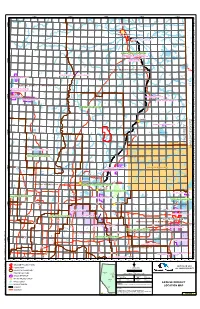

99 Birch Mountains NAMUR 98 Wildland 98 RIVER Gardiner McClelland Bu % Namur Lake ffalo LEGEND Lakes Lake B r uffalo Rive r Rive Mik % FORT kwa 97 Rive MCKAY ann r P y River 97 NAMUR Legend Lake LAKE TALBOT LAKE Wolve ri er 96 ne iv % C R 96 ac 88 Notikewin he UV Lié Creek ge River UV692 UV63 e ver 95 otik win Ri 95 N ELLS RIVER Fort BATTLE RIVER Mackay Bison % !( Lake 24 % PANNY 9 8 7 23 M 22 10 e 21 20 12 11 % ik r 19 le 94 17 % 15 14 ive 15 17 16 er A15 R P5 14 13 12 20 19 94 Riv 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 25 24 23 22 21 ls BISON LAKE El Five Year H o % tc h Lafond Creek ki s sR iver 741 r UV e 93 v i 93 S15 R n General Development o S14 o S L tee pbank Notikewin R PU92234 i !( ve Sawn Lake 2020-2024 r 92 PU92244 % 92 Plan Manning 2020-2024 CHIPEWYAN )" Northland aba LAKES 691 W s r UV c ve Forest Haig Lake a Ri Mink Lake Grew Lake Products Ltd/ North t[ Star 91 PU91244 91 !( 2020-2024 Operating Period: UV35 PU91234 2020-2024 D u nk irk Riv 2020 - 2025 90 LOON TROUT er PRAIRIE MOUNTAIN 90 iver Deadwood Peace River % MacKay R 690 !( UV C PU89254 S22 le a 2020-2024 rw 686 ate 89 UV r River Saprae adott iver OTTER LAKES 89 Little C e R Creek P4 Quitting Lake !( DEADWOOD % t[ UV69 RED EARTH % Chipewyan Lake Rd. -

GDP TEMPLATE 5-0.Mxd E H Er Os Iv U Lan

% r 918 2134 e iv R 148 Mink Lake o c h 476 te as P 265 108 C 2296 h M 921 70 i p i 975 1682 n 319 Hawkins Lake r k ve North L i a R R Randall k i o Wabasca v h e e c Lake e Lake R 457 r Sawle Lake st r a o e 43 P a iv R d i W River is i k ip McLeod Lake llo ni N Farrell Lake w R M Ho 158 i o 1784 r v l e e e Cre 359 i v Weaver Lake r ek o R Wabasca Utikoomak Lake ch t e 2777 No. 166B as Wabasca 139 No. P 29 Berry Wabasca No. 166A 80 155 Utikoomak Lake 116 Sander Lake Ho 11 10 9 Lake No. 166D ole Creek 23 22 No. 155A 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 26 25 24 Pastecho Lake Mistehae 50 Utikoomak Lake C1-P1 Willow South GIFT LAKE Lake No. 155 Wabasca Wabasca Utikumasis 278 55 U u Wabasca Lake Lake ti k No. 166D Wab m as % a River ca No. 166D R Wabasca 1478 iver Gift Lake caRiv No. 166 750 # s er 0 a tik UV b U um r a a ive C1-P3 W W R Wabasca Wabasca a 2938 Wabasca b C1-P2 Willow as No. 166D No. 166D ca i Calder Lake No. 166 R ver Gift Lake Utikuma Lake Willow 1693 1502 Little C1-P4 2441 79 Horse Lake Willow 50 727 736 r 7 e 1554 General 1503 i v R P a a McMullen Lake C3-P2 m k st C3-P3 Sandy Lake u e ec ik McConachie h t re Willow U C o C4-P2 Willow e Lake DOUCETTE s R r 361 iv 4 C4-P3 SANDY LAKE o er Willow 1690 H C2-P2 e l Willow 105 % t Development Plan Gift Lake t % Willow i L Brintnell d 971 e a 320 Lake t t o e R W c i r i llow llo rown u W R er w D e e i v R d Hor Pelican Lake o i se C w v C5-P1 e r 1501 D r e o e 367 T !9 k Marten 1632 1629 !9 !9 Nipisi Lake McMillan Lake # FMA0600043 (S17) 0 C 83 C2-P1 1715 !9 R 78 !9 Willow o 1993 a C6-P1 d 38 -

Viewed by the North American Journal Of

University of Alberta The Increasing Prevalence of Smaller Fish in Highly Exploited Fisheries: Concerns, Diagnosis and Management Solutions. Spine title: Active Adaptive Management to Address a Small Fish Problem. by Stephen Cameron Spencer A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Wildlife Ecology and Management Department of Renewable Resources ©Stephen Cameron Spencer Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Examining Committee A. Lee Foote, Renewable Resources Michael G. Sullivan, Renewable Resources David W. Schindler, Biological Sciences Mark A. Lewis, Biological Sciences Miles F. Dyck, Renewable Resources John R. Post, University of Calgary Abstract A decline in the size of fish within a population is concerning. Large-sized fish are ecologically important and valued for social and economic reasons. Following widespread collapses from angling overharvest, the densities of Walleyes Sander vitreus in Alberta’s lakes increased rapidly with large- minimum-size limits. -

MAP RAILWAY ! Disclaimer: HIGHWAY Prepared Solely for the Use of CNRL As Specified in the Accompanying Report

350000 400000 450000 500000 550000 Twp. 91 63 UV Twp. 90 6300000 Fort McMurray Twp. 89 CLEARWATER INDIAN RESERVE #175 69 UV Twp. 88 Twp. 87 Gordon Lake Gregoire Lake Provincial Park GREGOIRE LAKE GREGOIRE LAKE INDIAN RESERVE #176A INDIAN )"RESERVE #176B Twp. 86 Anzac Gipsy Lake GREGOIRE LAKE INDIAN RESERVE #176 6250000 Twp. 85 Garson Lake REGIONAL MUNICIPALITY OF WOOD BUFFALO UV956 Twp. 84 HOUSE RIVER INDIAN CEMETERY INDIAN RESERVE #178 WABASCA INDIAN RESERVE #166C Twp. 83 Patterson R i ard ch son Lake R i v Forrest Twp. 82 e MUNICIPAL DISTRICT OF OPPORTUNITY NO. 17 r Lake WABASCA INDIAN RESERVE #166B WABASCA INDIAN RESERVE #166A Twp. 81 UV754 Janvier WABASCA INDIAN RESERVE #166D JANVIER INDIAN RESERVE #194 Twp. 80 6200000 )" er WABASCA INDIAN RESERVE #166 iv COWPER LAKE INDIAN RESERVE #194A e R Descharm Twp. 79 Crow Lake Provincial Park Twp. 78 SASKATCHEWAN Conklin Twp. 77 )" WINEFRED LAKE INDIAN RESERVE #194B ALBERTA Twp. 76 Winefred Lake Twp. 75 6150000 UV813 UV881 Twp. 74 Twp. 73 JEAN BAPTISTE GAMBLER INDIAN RESERVE #183 Twp. 72 Calling Lake Provincial Park LAC LA BICHE COUNTY Twp. 71 2 Twp. 70 UV HEART LAKE INDIAN RESERVE #167 Cold Lake Air Weapons Range 6100000 La Biche River HEART LAKE INDIAN RESERVE #167A North Wabasca Lake UV858 Twp. 69 Lac la Biche Plamondon Twp. 68 Buffalo 663 River )" UV Dene COUNTY OF ATHABASCA NO. 12 Sir Winston Churchill Provincial Park Nation Wabasca IR166D Lac La Biche Twp. 67 )" Lakeland Provincial Park UV55 COLD LAKE INDIAN RESERVE #149C 855 Dillon Twp. 66 UV Lake Cross Lake Provincial Park BEAVER LAKE INDIAN RESERVE #131 Cold Lake Provincial Park 812 Marie Lake 663 Twp. -

Cardinal Decision (2018)

Date: 20180809 Docket: T-762-15 Citation: 2018 FC 822 Vancouver, British Columbia, August 9, 2018 PRESENT: The Honourable Madam Justice Roussel BETWEEN: CLIFFORD RAY CARDINAL Applicant And BIGSTONE CREE NATION, BIGSTONE CREE NATION COUNCIL, CHIEF GORDON T. AUGER, COUNCILLOR CLARA MOBERLY, COUNCILLOR BERT ALOOK, COUNCILLOR EDWARD BIGSTONE, COUNCILLOR JOSIE AUGER, COUNCILLOR STELLA NOSKIYE, COUNCILLOR ART BIGSTONE, COUNCILLOR FREDA ALOOK, COUNCILLOR IVAN ALOOK Respondents JUDGMENT AND REASONS I. Overview [1] The Applicant seeks judicial review of a decision made on March 24, 2015 by the Chief and Council of the Bigstone Cree Nation [BCN], removing him from his position as BCN Page: 2 Councillor for failing to comply with the residency requirements set out in the BCN Election Code. Under its terms, the Chief and Councillors are required to assume residency on the reserve for which they were elected within three (3) months of their election and to remain “permanently resident” there throughout their term of office. [2] The Applicant contends that the process by which he was removed from office was procedurally unfair and contravened the principles of natural justice. He also alleges that the residency requirement provisions in the BCN Election Code infringe his equality rights under subsection 15(1) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Part 1 of the Constitution Act, 1982, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, c 11 [Charter]. [3] The Respondents argue that the Applicant was afforded procedural fairness as he was given ample notice and opportunity to comply with the residency requirements prescribed by the BCN Election Code. -

Domestic Fishing Licence Conditions for 2020-2021

Domestic Fishing Licence Conditions for 2020-2021 This document and the rules within are effective April 1, 2020 The holder of a free-of-charge domestic fishing license can harvest fish for food for themselves and members of their immediate household from eligible waters listed below, using a gill net or rod and reel. Alberta's sportfishing rules (seasons, sizes and bag limits of fish) apply to all waterbodies that are not listed in the Domestic Fishing Licence Conditions (attachment to Domestic Fishing Licence). Fishing with gill nets Gill nets can be lawfully set by licenced users (i.e., First Nations people, Métis harvesters, and researchers). Nets must be visibly marked at each end with a 1 metre stake or spar buoy bearing the applicable licence number. See General and Specific rules for gillnetting below. If the nets are not marked, or the presence of a net seems suspicious (for example, set during a closed season), please call your local Fish and Wildlife Office or Report A Poacher at 1-800-642-3800. Specific rules for gillnetting See list and maps of waterbodies below with specific rules for gillnetting. If a waterbody is not identified on the list below, it is not eligible for gillnetting under the authority of a Domestic Fishing Licence. General rules for gillnetting 1. No gillnetting in waters closed to all fishing. 2. No spring closure unless specified for a lake or river. See table starting on page 3. 3. A single gill net of no more than 95 metres (104 yards) in length of the specified minimum mesh size (not less than or NLT) listed for the lake or river.