Target Date Funds: Characteristics and Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Principal Trustsm Target Date Collective Investment Funds (Target Date Funds) and Has Sole Discretion Over the Management of Each Target Date Fund

PROFILE Principal Trust SM Target Date Collective Investment Funds Portfolio Advisor: Principal Management Corporation Delaware Charter Guarantee & Trust Company, conducting business as Principal Trust Company (Principal Trust) is the Trustee of the Principal TrustSM Target Date Collective Investment Funds (Target Date Funds) and has sole discretion over the management of each Target Date Fund. Principal Management Corporation provides nondiscretionary investment advisory services to Principal Trust with respect to the Target Date Funds. Principal Trust Company makes investment decisions using advice provided by Principal Management Corporation. Investment Philosophy and Process Philosophy Launched in 2009, the Target Date Funds are a series of target date collective investment funds developed for qualified retirement plans. They are managed over time toward the approximate date the participant expects to start withdrawing money. Each Target Date Fund reflects what Principal Trust believes to be an optimal asset class mix — a combination of actively and passively managed equity, fixed income and real estate — for the respective target date. The Target Date Funds consist of distinct funds staged in five-year increments. Each Target Date Fund gradually becomes more conservative by increasing its exposure to traditionally more conservative underlying investment options and reducing its exposure to more aggressive underlying investment options as the target date nears. Not FDIC or NCUA insured May lose value • Not a deposit • No bank or credit union guarantee Not insured by any Federal government agency Asset allocation/diversification does not guarantee a profit or protect against a loss. 1 The Target Date Funds embrace a multi-asset class, multi-style and multi-manager strategy while providing broad diversification and an institutional-quality investment approach. -

Regulating On-Line Peer-To-Peer Lending in the Aftermath of Dodd-Frank: in Search of an Evolving Regulatory Regime for an Evolving Industry

DISCUSSION DRAFT Chaffee & Rapp Washington and Lee Law Review REGULATING ON-LINE PEER-TO-PEER LENDING IN THE AFTERMATH OF DODD-FRANK: IN SEARCH OF AN EVOLVING REGULATORY REGIME FOR AN EVOLVING INDUSTRY Eric C. Chaffee* Geoffrey C. Rapp** I. INTRODUCTION Like Congress’s prior attempt to legislate a post-bubble repair and prevention strategy for the American economy, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (Sarbanes-Oxley),1 the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 (Dodd-Frank) has received a somewhat chilly response from legal academics.2 As was the case with Sarbanes-Oxley,3 however, even amid all of the proposals included for the sake of “doing something” rather than for a strong policy justification, a few nuggets of genuine value can be found. One of those, in the case of Dodd-Frank, is the opening effort to address the regulatory gap surrounding on-line peer-to- * Associate Professor of Law and Chair of the Project for Law and Business Ethics, University of Dayton School of Law; J.D., University of Pennsylvania (2002); B.A., The Ohio State University (1999). I would like to thank Christine Gall, Esq. for support and encouragement while drafting this essay. ** Harold A. Anderson Professor of Law and Values, University of Toledo College of Law; J.D. Yale Law School (2001), A.B. Harvard College (1998). Eric Johnson (Toledo ’12) provided excellent research in support of portions of this article. 1 Sarbanes-Oxley Act, Pub. L. No. 107-204, 116 Stat. 745 (2002) (codified at 15 U.S.C. -

Proposed Rule: Investment Company Advertising: Target Date Retirement Fund Names and Marketing

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION 17 CFR Parts 230 and 270 [Release Nos. 33-9126; 34-62300; IC-29301; File No. S7-12-10] RIN 3235-AK50 INVESTMENT COMPANY ADVERTISING: TARGET DATE RETIREMENT FUND NAMES AND MARKETING AGENCY: Securities and Exchange Commission. ACTION: Proposed rule. SUMMARY: The Securities and Exchange Commission is proposing amendments to rule 482 under the Securities Act of 1933 and rule 34b-1 under the Investment Company Act of 1940 that, if adopted, would require a target date retirement fund that includes the target date in its name to disclose the fund’s asset allocation at the target date immediately adjacent to the first use of the fund’s name in marketing materials. The Commission is also proposing amendments to rule 482 and rule 34b-1 that, if adopted, would require marketing materials for target date retirement funds to include a table, chart, or graph depicting the fund’s asset allocation over time, together with a statement that would highlight the fund’s final asset allocation. In addition, the Commission is proposing to amend rule 482 and rule 34b-1 to require a statement in marketing materials to the effect that a target date retirement fund should not be selected based solely on age or retirement date, is not a guaranteed investment, and the stated asset allocations may be subject to change. Finally, the Commission is proposing amendments to rule 156 under the Securities Act that, if adopted, would provide additional guidance regarding statements in marketing materials for target date retirement funds and other investment companies that could be misleading. -

Target Date Funds: What's Under the Hood?

RETIREMENT RESEARCH January 2017, Number 17-2 TARGET DATE FUNDS: WHAT’S UNDER THE HOOD? By Edwin J. Elton, Martin J. Gruber, Andre de Souza, and Christopher R. Blake* Introduction In today’s 401(k) world, individuals must choose how in specialized assets, as well as conventional stocks to invest their retirement savings. Yet evidence shows and bonds; 2) TDF fees are only modestly higher than that they often make poor choices on their own.1 if an investor assembled a similar portfolio on his Target date funds (TDFs) were designed as a potential own; and 3) TDF investment returns are broadly in solution. TDFs provide a pre-set mix of stocks and line with other mutual funds; and TDF decisions on bonds, which shifts away from stocks and toward market timing and fund additions do not help, and bonds as individuals age. These funds are often used may hurt, performance. as the default option for 401(k)s that have automatic enrollment. By 2014, nearly 20 percent of all 401(k) assets were in TDFs, and about half of participants TDF Basics held these funds.2 Despite the growing prominence of TDFs, little A TDF is constructed from mutual funds, so it is a research has focused on the details of their holdings, “fund of funds.” TDFs are intended to provide a one- fees, and performance. This brief, adapted from a fund solution for investors that offers diversification recent study, uses data on TDFs and their underlying and a changing asset allocation mix with age. Each mutual fund investments that allows for a unique as- TDF has a “target” year and a pre-determined glide sessment of what is going on “under the hood.”3 path for gradually reducing the equity allocation as The discussion proceeds as follows. -

Horizons 2040 Through 2060 Target Date Funds

Horizons 2040 Through 2060 Target Date Funds Simplified Investment Risk/Potential Return Meter IMPORTANT INFORMATION: SIMPLIFIED ROUTE ADVANCED ROUTE SELF-DIRECTED ROKERAGE The Target Date Funds will be rebalanced each PORTFOLIO INFORMATION ASACCOUNT OF: OPTION quarter so that they maintain as closely as possible 06/30/2021 the established percentage of each investment INCEPTION DATE1: option.** Once the fund reaches its target date, •HORIZONS 2040-2045: 11/7/2008 the equity component will continue to be reduced for •HORIZONS 2050: 8/2/2010 10 additional years until the asset allocation matches that of the Horizons Retirement Income Fund. •HORIZONS 2055: 1/21/2015HORIZONS •HORIZONS 2060: 1/6/2020 **Rebalancing does not ensure a profit and does not protect PORTFOLIOCOBRAND OPERATING EXPENSES2: LOW HIGH against loss in declining markets. DODGER BLUE: PMS 2940.32% For Illustrative Purposes Only Holdings and composition of holdings are subject to change. SAVINGS Investment Objective Portfolio Information3: Horizons Target Date Funds are diversified portfolios ASSET FUND DIVERSIFICATION designed for people who want to leave ongoing 2.5% investment decisions to an experienced portfolio management team. The investor picks the Horizons Target Date Fund with the date closest to his or her LARGE CAP 7.4% expected retirement year. As the retirement date for MID CAP the fund gets closer, the asset mix (stock funds, bond SMALL CAP 15.0% 30.7% funds and other investments) gradually adjusts to a more NON-U.S. conservative asset mix until it eventually consolidates into EMERGING MARKET the Retirement Income Fund (generally, it takes 10 years EQUITY ALTERNATIVES 12.2% from the “targeted” year for the fund to consolidate REAL RETURN 6.6% into the Retirement Income Fund). -

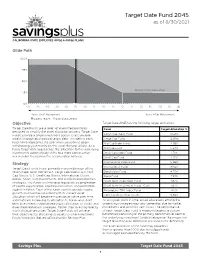

Target Date 2045 Fund Fact Sheet

Target Date Fund 2045 as of 6/30/2021 Glide Path 100% 75% 50% Steady State Allocation 25% 0% 50 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 Years Until Retirement Years After Retirement Equities 79.47% Cash/Bonds 20.53% Objective Target Date 2045 has the following target allocations: Target Date Funds are a series of diversified portfolios Fund Target Allocation % designed to simplify the asset allocation process. Target Date Funds provide a single investment option to accumulate Large Cap Index Fund 10.28% wealth through an expected target date. The date in each Large Cap Fund 14.69% fund name represents the year when you plan to begin Mid Cap Index Fund 4.28% withdrawing your money (in this case, the year 2045). As a funds target date approaches, the allocation to the underlying Mid Cap Fund 5.34% investments automatically shifts to a more conservative Small Cap Index Fund 1.71% mix in order to preserve the accumulated balance. Small Cap Fund 2.13% Strategy International Index Fund 15.86% International Fund 19.82% Target Date Funds invest primarily in a combination of the seven major asset classes U.S. Large Cap Stocks, U.S. Mid Bond Index Fund 4.75% Cap Stocks, U.S. Small Cap Stocks, International Stocks, Bond Fund 7.93% Bonds, Short Term Investments, and Diversified Real Return Short Term Investment Fund 1.87% strategies. The funds are intended to provide a combination of capital appreciation, capital preservation, and protection Short Term Investment Fund - Cash 1.87% against inflation. -

Designing the Future of Target-Date Funds: a New Blueprint for Improving Retirement Outcomes

Designing the Future of Target-Date Funds: A New Blueprint for Improving Retirement Outcomes Daniel Loewy Executive Summary and time-tested, beyond traditional equity and AllianceBernstein (AB) fixed income. These strategies can help reduce Target-date funds are the key to the future sensitivity to market, interest-rate and inflation Christopher Nikolich of retirement savings for American workers. risks at different points in the glide path. And AllianceBernstein (AB) While these funds have seen tremendous diversifying against these risks can improve asset growth over the past decade, their overall outcomes versus a traditional glide path investment design hasn’t kept pace with roughly 80% of the time. available innovations. The result: many target- date strategies may fail to guard against today’s We see five key areas (Exhibit 1, next page) for heightened retirement risks. evolving the state of target-date design: It’s time to revisit target-date fund designs and • Moving from a single investment single-manager structures. Most retirement manager to a multi-manager or plans still use traditional designs that were open-architecture format to access adopted years ago, but fiduciary standards have best-of-breed managers and reduce changed. In fact, the US Department of Labor concentration risk (DOL) has issued “Target Date Retirement • Diversifying the underlying investment Funds: Tips for ERISA Plan Fiduciaries,” which mix from a traditional stock/bond glide highlights the need for plan sponsors to have a path to incorporate nontraditional asset solid process for selecting and monitoring their classes, too target-date choice. • Providing greater flexibility to respond The investment environment has changed, too. -

Regulatory Changes for Chinese Stocks Remaining on Track

November 30, 2020 PIonline.com $16 an issue / $350 a year THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSPAPER OF MONEY MANAGEMENT Jennifer Bishop MORE HEADACHES: Washington Will Hansen believes recent inquiries related to ESG issues are yet Regulatory changes another cause for plan sponsor concern. for Chinese stocks remaining on track Stricter accounting rules, RELATED NEWS ban on military investing n Overseas investors flocking to in future for U.S. investors Chinese government bonds. Page 2 n New rules unlikely to derail China’s e-commerce giants. Page 2 By HAZEL BRADFORD Regulation Earlier this month, a White House Despite big changes at the White executive order banned investing in House in 2021, the push to protect U.S. Chinese companies linked to its mili- investors in Chinese companies is still tary. As of Jan. 1, individuals or compa- EBSA broadening its focus on enforcement on track, as regulators prepare to hold nies can no longer own direct shares the companies to tougher accounting or funds holding shares in 31 Chinese Labor Department agency gets Earlier this year, the Labor Department began standards and some face an outright ban. companies identified as security risks. sending enforcement letters to plan sponsors and “There will continue to be tension Many more U.S. investors will be af- busy on several different fronts registered investment adviser firms requesting between the U.S. and China — even fected by accounting rules expected to documents pertaining to environmental, social with a new administration taking the be proposed next month by the Securi- By BRIAN CROCE and governance-themed fund decisions. -

Target Date 2060 Fund

TARGET DATE 2060 FUND Note: This fund fact sheet provides information regarding the Target Date 2060 Fund, including investment objectives, strategy and fees. A Morningstar fund fact sheet, which includes performance and portfolio information, is anticipated to be available in late October 2020. In the meantime, you may also view the Morningstar fund fact sheet for the Target Date 2055 Fund, because the asset allocation of the Target Date 2055 Fund is identical at this time and is not expected to diverge for a number of years. To view the Morningstar fund fact sheet for the Target Date 2055 Fund, click on the investment overview document under INVESTMENTS > Investment lineup on the 401(k) Savings Plan Web Center. INVESTMENT TYPE INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT FEES The Target Date Funds are lifecycle investment options Fees are deducted from the investment performance of comprising a mix of underlying investment funds the Target Date Fund and are based on the investment across a broad range of asset classes. allocations and the investment management fees and administrative fees (if any) associated with each underlying INVESTMENT OBJECTIVE fund. For example, the Target Date 2060 Fund has estimated investment management and administrative The Target Date 2060 Fund is a broadly diversified fees of 3 basis points (0.03%), meaning the fee on a portfolio that seek total return as appropriate for the $1,000 investment would be about $0.30 annually. These target date listed within the fund name (2060). Target fees are referred to as the expense ratio or operating Date Funds invest in a mix of equity, fixed income, Real expenses. -

The Evolution of Target Date Funds: Using Alternatives to Improve Retirement Plan Outcomes

The Evolution of Target Date Funds: Using Alternatives to Improve Retirement Plan Outcomes Angela M. Antonelli Executive Director Georgetown University Center for Retirement Initiatives In conjunction with: Willis Towers Watson Policy Report 18-01 June 2018 About the Center for Retirement Initiatives (CRI) The Center for Retirement Initiatives is a research center of the McCourt School of Public Policy, one of the top-ranked public policy programs in the nation. Through its academic reputation and ability to engage with policymakers, business leaders and other stakeholders, the McCourt School attracts world-class scholars and students who have become leaders in the public, private and nonprofit sectors. The CRI is dedicated to: Strengthening retirement security by expanding access and coverage for the private sector workforce Providing thought leadership and developing innovative new approaches to retirement savings, investment and lifetime income Serving as a trusted policy advisor to federal, state and local policymakers and stakeholders 3300 Whitehaven Street, NW, 5th Floor Washington, D.C. 20007 (202) 687-4901 https://cri.georgetown.edu/ About Willis Towers Watson Willis Towers Watson (NASDAQ: WLTW) is a leading global advisory, broking and solutions company that helps clients around the world turn risk into a path for growth. With roots dating to 1828, Willis Towers Watson has over 40,000 employees serving more than 140 countries. We design and deliver solutions that manage risk, optimize benefits, cultivate talent, and expand the power of capital to protect and strengthen institutions and individuals. Our unique perspective allows us to see the critical intersections between talent, assets and ideas – the dynamic formula that drives business performance. -

Ready! Fire! Aim? 2018 Updated Findings from Over a Decade of Research Into Real-World Participant Saving and Withdrawal Patterns ABOUT

FOR INSTITUTIONAL USE ONLY | NOT FOR PUBLIC DISTRIBUTION RETIREMENT INSIGHTS Ready! Fire! Aim? 2018 Updated findings from over a decade of research into real-world participant saving and withdrawal patterns ABOUT READY! FIRE! AIM? SERIES The Ready! Fire! Aim? research series is an ongoing study that analyzes how participants are engaging with defined contribution (DC) plans and how these saving and withdrawal behaviors can interact with target date fund design. Our original research, published in 2007, found participant behavior was much more varied and volatile than many target date fund providers had assumed in their asset allocation models, with significant ramifications around potential outcomes. These trends continued to be confirmed in our subsequent research updates in 2009, 2012, 2015 and now 2018. Participants are saving too little, on average; many are taking loans, and most quickly withdraw assets after retiring. This elevated cash flow volatility has a potentially negative amplifying effect on portfolio volatility. WHAT IS NEW FOR 2018? Expanded data universe This year, we evaluated an expanded participant universe that draws from MassMutual Financial Group and Empower Retirement, which together are record keepers for approximately 4,000 defined contribution plans serving more than two million participants. This more diverse and robust data set allows for a deeper analysis, with perspectives on how enrollment and salary can shape behaviors. Higher retirement hurdle Participants may have to accumulate even more to achieve safe retirement funding levels: • Replacement income targets are slightly up for the average participant. • Long-term market expectations remain generally lower. • The full-benefit age for Social Security continues to increase. -

Target Date Funds WHITEPAPER AUGUST 2020

Target Date Funds WHITEPAPER AUGUST 2020 With the significant reduction in defined benefit retirement plans in the United CONTRIBUTORS States, the burden of investing retirement portfolios has been placed on the backs David Suh, CAIA Hannah Schriner of individual participants, primarily in defined contribution plans. Historically, Paul Cowie III individuals have significantly underperformed institutional investors due to a David Smith lack of time, information, and expertise in managing investments. Target date funds (“TDFs”) were created in an effort to bridge the gap between professionally managed pension funds and participant directed retirement plans with the goal of increasing the likelihood that individuals could achieve their retirement income goals. This paper first provides a brief history of TDFs, followed by a discussion of fund mechanics and their pros and cons. Finally, it provides a review of the marketplace and likely future trends that should help plan sponsors make informed decisions regarding the use of TDFs. We conclude that TDFs represent an important aspect of defined contribution plan design, and should be included in a plan’s investment menu. Introduction The goal of Target Date Funds (“TDFs”) is to provide participants with “one stop shopping” for their retirement savings needs and eliminate the need to choose among several investment options to formulate an appropriate asset allocation. TDFs utilize varied approaches, but the consistent theme among them is a focus on the investor’s time horizon (as defined by an expected retirement date) as the key determinant of his or her risk tolerance. Typically, a suite of TDFs are offered to plan participants in five-year increments that correspond to particular retirement dates.