The Connexion of Natural and Divine Truth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Augustine on Knowledge

Augustine on Knowledge Divine Illumination as an Argument Against Scepticism ANITA VAN DER BOS RMA: RELIGION & CULTURE Rijksuniversiteit Groningen Research Master Thesis s2217473, April 2017 FIRST SUPERVISOR: dr. M. Van Dijk SECOND SUPERVISOR: dr. dr. F.L. Roig Lanzillotta 1 2 Content Augustine on Knowledge ........................................................................................................................ 1 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................ 4 Preface .................................................................................................................................................... 5 Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 7 The life of Saint Augustine ................................................................................................................... 9 The influence of the Contra Academicos .......................................................................................... 13 Note on the quotations ........................................................................................................................ 14 1. Scepticism ........................................................................................................................................ -

Francis Bacon´S Philosophy Under Educational Perspective

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 3 No. 17; September 2013 Francis Bacon´S Philosophy under Educational Perspective Gustavo Araújo Batista – PhD Docent at Master Degree Program University of Uberaba - Brazil Abeuntstudia in mores. Francis Bacon Abstract This article has as main objective to make a concise approach about Francis Bacon’s (1561-1626) philosophy, dimensioning it inside educational area. It will be done a summary explanation of his historical context (Renaissance), of some of his works and of some of the main topics of his philosophy, demonstrating its applicability to pedagogy. By developing a conceptual and contextual approach, this study has adopted as its theoretical-methodological reference the historical-dialectical materialism, according to Lucien Goldmann (1913-1970), appointing as main result the alert done by Bacon in relation to knowledge usefulness in order to improve human being´s lifetime, this knowledge that, identifying itself to power, it allows to mankind to dominate natural world and, equally, to itself, wining, so, its own weakness and limitations, because its own ignorance is the root of the evils of which suffer, as well as the material and spiritual difficulties in the presence of which it founds itself, reason for which education, by adopting that conception as one of its foundation, there will be thought and practiced in a way to be aware to the responsibility that knowledge brings with itself. Keywords: Education. Francis Bacon. Philosophy. Science. Introduction This text has as its objective to deal with, summarily, the thought of the English philosopher Francis Bacon (1561-1626), appointing, simultaneously, its convergences to educational field. -

INTRODUCTION 1. Medical Humanism and Natural Philosophy

INTRODUCTION 1. Medical Humanism and Natural Philosophy The Renaissance was one of the most innovative periods in Western civi- lization.1 New waves of expression in fijine arts and literature bloomed in Italy and gradually spread all over Europe. A new approach with a strong philological emphasis, called “humanism” by historians, was also intro- duced to scholarship. The intellectual fecundity of the Renaissance was ensured by the intense activity of the humanists who were engaged in collecting, editing, translating and publishing the ancient literary heri- tage, mostly in Greek and Latin, which had hitherto been scarcely read or entirely unknown to the medieval world. The humanists were active not only in deciphering and interpreting these “newly recovered” texts but also in producing original writings inspired by the ideas and themes they found in the ancient sources. Through these activities, Renaissance humanist culture brought about a remarkable moment in Western intel- lectual history. The effforts and legacy of those humanists, however, have not always been appreciated in their own right by historians of philoso- phy and science.2 In particular, the impact of humanism on the evolution of natural philosophy still awaits thorough research by specialists. 1 By “Renaissance,” I refer to the period expanding roughly from the fijifteenth century to the beginning of the seventeenth century, when the humanist movement begun in Italy was difffused in the transalpine countries. 2 Textbooks on the history of science have often minimized the role of Renaissance humanism. See Pamela H. Smith, “Science on the Move: Recent Trends in the History of Early Modern Science,” Renaissance Quarterly 62 (2009), 345–75, esp. -

Draft Informational Report Chabot Gun Club and Facility Operations at Anthony Chabot Marksmanship Range Revised October 28, 2015

Draft Informational Report Chabot Gun Club and Facility Operations at Anthony Chabot Marksmanship Range Revised October 28, 2015 I. Introduction The Board of Directors (“Board”) has requested information relating to facility operations at the Anthony Chabot Marksmanship Range (“Chabot Gun Range” or “gun range”), including estimated capital and operation and maintenance costs required for continued operation of the gun range. As discussed below, District staff has gathered information regarding environmental compliance, facility conditions and deferred maintenance, sound impacts and mitigation options, and information related to use, revenue, and operational costs of the gun range. II. CEQA Compliance No action by the Board is being requested at this time, and therefore no action is necessary to comply with CEQA for purposes of this Board item. However, a decision by the Board to consider entry into a long term extension of the Chabot Gun Club’s lease would first require environmental review under CEQA, most likely the preparation of an environmental impact report (EIR). III. History of the Chabot Gun Range In 1963, the Anthony Chabot Marksmanship Range was developed in cooperation with the Oakland Pistol Club, which had previously leased a site in Knowland Park, Oakland, California. The original 1962 lease was a partnership between the District and the Oakland Pistol Club to construct, develop, operate and maintain a marksmanship range in Anthony Chabot Regional Park. In 1964, the original lease was amended to finalize the schedule and define the cost-share for construction of the Chabot Gun Range. In 1967, the District entered into a new long-term lease with Chabot Gun Club, Inc. -

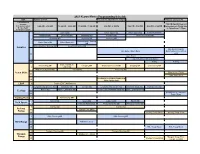

2021 Camp Keowa Master Programming Schedule

2021 Keowa Master Programming Schedule KEY Update: 2/17/21 ←Lunch 12:15pm/Siesta 1:00pm ←Dinner Lineup 5:45 I = instructional program 7:00 PM (Spirit Program) O = open program 9:00 AM - 9:50 AM 10:00 AM - 10:50 AM 11:00 AM - 11:50 AM 2:00 PM - 2:50 PM 3:00 PM - 3:50 PM 4:00 PM - 4:50 PM No program on Friday due B = bookable to Campfire at 7:30pm A = Adult Program BSA Guard Water Sports MB Water Sports MB Instructional Swim Swimming MB Swimming MB Swimming MB Kayaking MB Small Boat Sailing MB Lifesaving MB Kayaking MB Canoeing MB I Motor Boating / Rowing Water Sports MB Water Sports MB MB Aquatics Motor Boating / Rowing MB Small Boat Sailing MB Mile Swim/ Rowing Mile Swim (Thurs Only) Qualifications (Tues/Wed O only) Open Swim Open Boating (ends at 4:30pm) B Tubing Tubing Signs, Signals, & Geocaching MB Camping MB Wilderness Survival MB Camping MB Orienteering MB I Codes MB Wilderness Survival MB First Aid MB Pioneering MB Scout Skills Firem'n Chit (Thurs) O Totin' Chip (Tues) Introduction to Outdoor Leadership A Skills (Adults Only) LEAF I Project LEAF (AM Session) Envionmental Science MB Astronomy MB Forestry MB Environmental Science MB Mammal Study MB Plant Science MB I Ecology Nature MB Space Exploration MB Reptile and Amphibian Study MB Space Exploration MB Introduction to Leave No O Trace (Tues) Trading Post I Salemanship MB Fishing MB Sports MB Athletics MB Sports MB Field Sports I Personal Fitness MB Personal Fitness MB Personal Fitness MB I Archery MB Archery MB Archery O Archery Free Shoot Range B Archery Troop Shoot Archery -

'An Incredibly Vile Sport': Campaigns Against Otter Hunting in Britain

Rural History (2016) 27, 1, 000-000. © Cambridge University Press 2016 ‘An incredibly vile sport’: Campaigns against Otter Hunting in Britain, 1900-39 DANIEL ALLEN, CHARLES WATKINS AND DAVID MATLESS School of Physical and Geographical Sciences, University of Keele, ST5 5BG, UK [email protected] School of Geography, University of Nottingham, University Park, Nottingham, NG7 2RD, UK [email protected] [email protected] Abstract: Otter hunting was a minor field sport in Britain but in the early years of the twentieth century a lively campaign to ban it was orchestrated by several individuals and anti-hunting societies. The sport became increasingly popular in the late nineteenth century and the Edwardian period. This paper examines the arguments and methods used in different anti-otter hunting campaigns 1900-1939 by organisations such as the Humanitarian League, the League for the Prohibition of Cruel Sports and the National Association for the Abolition of Cruel Sports. Introduction In 2010 a painting ‘normally considered too upsetting for modern tastes’ which ‘while impressive’ was also ‘undeniably "gruesome"’ was displayed at an exhibition of British sporting art at the Bowes Museum, Barnard Castle. The Guardian reported that the grisly content of the painting was ‘the reason why it was taken off permanent display by its owners’ the Laing Gallery in Newcastle.1 The painting, Sir Edwin Landseer’s The Otter Speared, Portrait of the Earl of Aberdeen's Otterhounds, or the Otter Hunt had been associated with controversy since it was first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1844 Daniel Allen, Charles Watkins and David Matless 2 (Figure 1). -

An Introduction to Philosophy

An Introduction to Philosophy W. Russ Payne Bellevue College Copyright (cc by nc 4.0) 2015 W. Russ Payne Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document with attribution under the terms of Creative Commons: Attribution Noncommercial 4.0 International or any later version of this license. A copy of the license is found at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ 1 Contents Introduction ………………………………………………. 3 Chapter 1: What Philosophy Is ………………………….. 5 Chapter 2: How to do Philosophy ………………….……. 11 Chapter 3: Ancient Philosophy ………………….………. 23 Chapter 4: Rationalism ………….………………….……. 38 Chapter 5: Empiricism …………………………………… 50 Chapter 6: Philosophy of Science ………………….…..… 58 Chapter 7: Philosophy of Mind …………………….……. 72 Chapter 8: Love and Happiness …………………….……. 79 Chapter 9: Meta Ethics …………………………………… 94 Chapter 10: Right Action ……………………...…………. 108 Chapter 11: Social Justice …………………………...…… 120 2 Introduction The goal of this text is to present philosophy to newcomers as a living discipline with historical roots. While a few early chapters are historically organized, my goal in the historical chapters is to trace a developmental progression of thought that introduces basic philosophical methods and frames issues that remain relevant today. Later chapters are topically organized. These include philosophy of science and philosophy of mind, areas where philosophy has shown dramatic recent progress. This text concludes with four chapters on ethics, broadly construed. I cover traditional theories of right action in the third of these. Students are first invited first to think about what is good for themselves and their relationships in a chapter of love and happiness. Next a few meta-ethical issues are considered; namely, whether they are moral truths and if so what makes them so. -

MATERIALISM: a HISTORICO-PHILOSOPHICAL INTRODUCTION Charles Wolfe

MATERIALISM: A HISTORICO-PHILOSOPHICAL INTRODUCTION Charles Wolfe To cite this version: Charles Wolfe. MATERIALISM: A HISTORICO-PHILOSOPHICAL INTRODUCTION. MATERI- ALISM: A HISTORICO-PHILOSOPHICAL, Springer International Publishing, 2016, Springer Briefs, 978-3-319-24818-9. 10.1007/978-3-319-24820-2. hal-01233178 HAL Id: hal-01233178 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01233178 Submitted on 24 Nov 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. MATERIALISM: A HISTORICO-PHILOSOPHICAL INTRODUCTION Forthcoming in the Springer Briefs series, December 2015 Charles T. Wolfe Centre for History of Science Department of Philosophy and Moral Sciences Ghent University [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 (Introduction): materialism, opprobrium and the history of philosophy Chapter 2. To be is to be for the sake of something: Aristotle’s arguments with materialism Chapter 3. Chance, necessity and transformism: brief considerations Chapter 4. Early modern materialism and the flesh or, forms of materialist embodiment Chapter 5. Vital materialism and the problem of ethics in the Radical Enlightenment Chapter 6. Naturalization, localization: a remark on brains and the posterity of the Enlightenment Chapter 7. Materialism in Australia: The Identity Theory in retrospect Chapter 8. -

In the Polite Eighteenth Century, 1750–1806 A

AMERICAN SCIENCE AND THE PURSUIT OF “USEFUL KNOWLEDGE” IN THE POLITE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY, 1750–1806 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Notre Dame in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Elizabeth E. Webster Christopher Hamlin, Director Graduate Program in History and Philosophy of Science Notre Dame, Indiana April 2010 © Copyright 2010 Elizabeth E. Webster AMERICAN SCIENCE AND THE PURSUIT OF “USEFUL KNOWLEDGE” IN THE POLITE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY, 1750–1806 Abstract by Elizabeth E. Webster In this thesis, I will examine the promotion of science, or “useful knowledge,” in the polite eighteenth century. Historians of England and America have identified the concept of “politeness” as a key component for understanding eighteenth-century culture. At the same time, the term “useful knowledge” is also acknowledged to be a central concept for understanding the development of the early American scientific community. My dissertation looks at how these two ideas, “useful knowledge” and “polite character,” informed each other. I explore the way Americans promoted “useful knowledge” in the formative years between 1775 and 1806 by drawing on and rejecting certain aspects of the ideal of politeness. Particularly, I explore the writings of three central figures in the early years of the American Philosophical Society, David Rittenhouse, Charles Willson Peale, and Benjamin Rush, to see how they variously used the language and ideals of politeness to argue for the promotion of useful knowledge in America. Then I turn to a New Englander, Thomas Green Fessenden, who identified and caricatured a certain type of man of science and satirized the late-eighteenth-century culture of useful knowledge. -

Technical Review 12-04 December 2012

The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation Technical Review 12-04 December 2012 1 The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation The Wildlife Society and The Boone and Crockett Club Technical Review 12-04 - December 2012 Citation Organ, J.F., V. Geist, S.P. Mahoney, S. Williams, P.R. Krausman, G.R. Batcheller, T.A. Decker, R. Carmichael, P. Nanjappa, R. Regan, R.A. Medellin, R. Cantu, R.E. McCabe, S. Craven, G.M. Vecellio, and D.J. Decker. 2012. The North American Model of Wildlife Conservation. The Wildlife Society Technical Review 12-04. The Wildlife Society, Bethesda, Maryland, USA. Series Edited by Theodore A. Bookhout Copy Edit and Design Terra Rentz (AWB®), Managing Editor, The Wildlife Society Lisa Moore, Associate Editor, The Wildlife Society Maja Smith, Graphic Designer, MajaDesign, Inc. Cover Images Front cover, clockwise from upper left: 1) Canada lynx (Lynx canadensis) kittens removed from den for marking and data collection as part of a long-term research study. Credit: John F. Organ; 2) A mixed flock of ducks and geese fly from a wetland area. Credit: Steve Hillebrand/USFWS; 3) A researcher attaches a radio transmitter to a short-horned lizard (Phrynosoma hernandesi) in Colorado’s Pawnee National Grassland. Credit: Laura Martin; 4) Rifle hunter Ron Jolly admires a mature white-tailed buck harvested by his wife on the family’s farm in Alabama. Credit: Tes Randle Jolly; 5) Caribou running along a northern peninsula of Newfoundland are part of a herd compositional survey. Credit: John F. Organ; 6) Wildlife veterinarian Lisa Wolfe assesses a captive mule deer during studies of density dependence in Colorado. -

HISTORICAL SKETCH of RURAL FIELD SPORTS in LANCASTER COUNTY by Herbert H

I. HISTORICAL SKETCH OF RURAL FIELD SPORTS IN LANCASTER COUNTY By Herbert H. Beck A consideration of the purposes and value of history requires that the historian be properly qualified as a witness before the bar of posterity. In cases such as the one at hand this qualification should reach the point of showing not only that the writer be in close and accurate touch with the past but that he have a technical knowledge of his subject. Before such examination the writer modestly presumes to eligibility. He believes that while this sketch might have been written by men whose memories reach farther back than his own by thirty of forty years, it could have been done by none of this generation perhaps whose interest in the field sports of Lancaster County has been keener nor whose experience has been more widely ranged than his over the various phases of the subject. From a boyhood in which the writings of Frank Forrester had their quick appeal and the sportsmen of his village took on a heroism he has found his keenest recreation afield. Following an ancient instinct which, though it may have softened, has not turned with years he has entered enthusias- tically at one time or another into all of the sportsmanly kinds of local hunting. He has splashed through the tussock swamps of many townships hunting snipe on the spring migration; he has been in parties of woodcock shooters in the days prior to 1904 when July cock-shooting was the accepted mid-summer sport; he has spent scores of August afternoons in the up- country farmlands in pursuit of -

British Christianity During the Roman Occupation

British Christianity during the Roman Occupation BY RICHARD VALPY FRENCH, D.C.L., LL.D., F.S.A. EXA.MfNING CHAPLAIN TO THE BISHOP OF LLANDAFP-, RURAL DEAN OF CAERLEON, RECTOR OF LLANMARTIN AND WILCRICK. PUBLISHED UNDER THE DIRECTION 01' THE TRACT COMMITTEE. !::iOCIETY FOR PROMOTING CHRISTIAN KNOWLEDGE, LONDON: NORTHUMBERLAND AVENUE, W.C.; 43 1 QUEEN VICTORIA STREET, E.C. BRIGHTON: 129, NORTH STREET. NEw YoRK: E. & J. B. YOUNG & CO. 1900 R1cHARn CLAY & Som;, LIMJTED, LONDON & BUNGAY. British · Christianity during the Roman Occupation THE object of this paper is to present an intelligible idea of Christianity in Britain during the Roman occupation; that is to say (speaking. roughly), during the first four centuries of th.e Christian era. The endeavour will be made to disentangle from a mass of legend, which Celtic patriotism or controversial zeal has hugged, the meagre scraps of real history for which we are indebted to foreign rather than to native historians. A bitter wail has reverberated from the first to the last of the writers of our soil, from the British Gildas of the sixth century to Professor Bright of to-day, that native contemporary records are non-existent, that the first planting of the faith is unknown.1 1 A really exhaustive study might take some such form as- Direct. Indirect (e.g. the study of Historical . the concurrent history of { Christianity in Ireland, Gaul, etc.). SOURCES Architectural. Monumental. Arch~ological Philological. { Paheographical. , Anthropological. Traditional-Folk-lore. 4 BRITISH CHRISTIANITY The plan here adopted is, to begin with the earliest available evidence of the settled condition of the British Church, namely, the, presence of three British bishops at the Synod of Arles (A.D.314).1 This will serve as a chronological point d'appui from which to proceed, first onward to the end of the proposed period, and then backward, till we arrive at the vanishing point of anything like British history, which we believe to be coin cident with the origin of British Christianity.