The Path to Gram Swaraj in Karnataka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ಕ ೋವಿಡ್ ಲಸಿಕಾಕರಣ ಕ ೋೇಂದ್ರಗಳು (COVID VACCINATION CENTRES) Sl No District CVC Na

ಕ ೋ풿蓍 ಲಕಾಕರಣ ಕ ೋᲂ飍ರಗಳು (COVID VACCINATION CENTRES) Sl No District CVC Name Category 1 Bagalkot SC Karadi Government 2 Bagalkot SC TUMBA Government 3 Bagalkot Kandagal PHC Government 4 Bagalkot SC KADIVALA Government 5 Bagalkot SC JANKANUR Government 6 Bagalkot SC IDDALAGI Government 7 Bagalkot PHC SUTAGUNDAR COVAXIN Government 8 Bagalkot Togunasi PHC Government 9 Bagalkot Galagali Phc Government 10 Bagalkot Dept.of Respiratory Medicine 1 Private 11 Bagalkot PHC BENNUR COVAXIN Government 12 Bagalkot Kakanur PHC Government 13 Bagalkot PHC Halagali Government 14 Bagalkot SC Jagadal Government 15 Bagalkot SC LAYADAGUNDI Government 16 Bagalkot Phc Belagali Government 17 Bagalkot SC GANJIHALA Government 18 Bagalkot Taluk Hospital Bilagi Government 19 Bagalkot PHC Linganur Government 20 Bagalkot TOGUNSHI PHC COVAXIN Government 21 Bagalkot SC KANDAGAL-B Government 22 Bagalkot PHC GALAGALI COVAXIN Government 23 Bagalkot PHC KUNDARGI COVAXIN Government 24 Bagalkot SC Hunnur Government 25 Bagalkot Dhannur PHC Covaxin Government 26 Bagalkot BELUR PHC COVAXINE Government 27 Bagalkot Guledgudd CHC Covaxin Government 28 Bagalkot SC Chikkapadasalagi Government 29 Bagalkot SC BALAKUNDI Government 30 Bagalkot Nagur PHC Government 31 Bagalkot PHC Malali Government 32 Bagalkot SC HALINGALI Government 33 Bagalkot PHC RAMPUR COVAXIN Government 34 Bagalkot PHC Terdal Covaxin Government 35 Bagalkot Chittaragi PHC Government 36 Bagalkot SC HAVARAGI Government 37 Bagalkot Karadi PHC Covaxin Government 38 Bagalkot SC SUTAGUNDAR Government 39 Bagalkot Ilkal GH Government -

84-Haveri(SC). Haveri

Name and Address of the BLOs District: 11- Name of Assembly Constituency: 84-Haveri(SC). Haveri. Total No. of Parts in the AC: 200 Total No. of BLOs in the AC: 200 Part No. Name of the BLO Complete Address of the Contact No. 1 2 3 4 1 S R Kale Yalavigi 9480868382 2 I N Mudagal Yalavigi 9972517743 3 P C Sankappanaver Yalavigi 9482237117 4 S B Kalasad Yalavigi 9980607357 5 F C Goddemmi Marutipur 9481682261 6 A M Kattimani Huvinashigli 9480868369 7 M P Pradeepa Huvinashigli - 8 I K Jafarnavar Basavanakoppa 9632552724 9 J N doddamani Hesarur 9902221151 10 F. S. Vadavi Hesarur 8095742363 11 M D Pawar Siddapur 9980684530 12 N V Baligar Siddapur 9902109902 13 S. K Ratod kalival 0 14 H. N Avin Kadakol 9880174921 15 M V Kolli Kadakol 9538355975 16 S M Savanur Kadakol 9741305885 17 N H Ramgiri Kadakol 9008377849 18 U. K Bevingidad Vadnikoppa 8095069588 19 N B Patil Naikerur 7760364777 20 M C Kalimath Honnikoppa 0 21 S.C Halappanavar Sirabadagi 9740020359 22 M T Hugar Sirabadagi 9980647575 23 S H Shettihalli Sevalapur 9242366562 24 S. S. Salimath Kalakond 9740915725 25 A J Kumbar Jallapur - 26 M K Shanbal Jallapur 9980426669 27 A A Hajarathnavar Hattimattur 0 28 N S Adur Hattimattur 9686312700 29 R C Dyamanagouder Hattimattur 9902780216 30 S.C. Kattikai Hattimattur 9741763437 31 J B.Maralavar Hattimattur Tanda 0 32 S O Hattikala Krisnapur 9902229160 33 I D Nandi Hiremarlihalli 9946607918 34 A H Mattur Chikkamarlihalli 9902653488 35 B.H.Kulkarni Melmuri 9972664004 36 S B Sajjan Biarapur 9900434403 37 N. -

Pre-Feasibility Report and Draft Terms of Reference

PRE-FEASIBILITY REPORT AND DRAFT TERMS OF REFERENCE OF EXPANSION OF TUBACHI BABALESHWARA LIFT IRRIGATION SCHEME TO EXPAND A COMMAND AREA FROM 42,500 TO 52,700 Ha NEAR KAVATAGI VILLAGE, JAMAKHANDI TALUK, BAGALKOT DISTRICT SCHEDULE 1(C) OF EIA NOTIFICATION, 2006, CATEGORY – A, TOTAL COST OF THE PROJECT – 3572.00 CRORES Submitted to THE DIRECTOR AND MEMBER SECRETARY, RIVER VALLEY AND HYDROELECTRIC PROJECTS, MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT, FORESTS AND CLIMATE CHANGE (MOEF), GOVT. OF INDIA NEW DELHI - 110003. Submitted by THE CHIEF ENGINEER KARNATAKA NEERAVARI NIGAMA LTD., IRRIGATION NORTH ZONE BELAGAVI – 590001 KARNATAKA Prepared by ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH & SAFETY CONSULTANTS PVT LTD # 13/2, 1ST MAIN ROAD, NEAR FIRE STATION, NABET/ EIA/ RA080/ 55 Dated: 03.12.2015 INDUSTRIAL TOWN, RAJAJINAGAR,BENGALURU-560 010, KARNATAKA SEPTEMBER 2017 Expansion of Tubachi-Babaleshwara Lift Irrigation Scheme PFR & Draft ToRs near Kavatagi village, Jamakhandi taluk, Bagalkot District Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary ......................................................................... 1 2. Introduction of the Project/ Background Information .......................... 3 3. Project Description .........................................................................15 4. Site Analysis ..................................................................................27 5. Planning ........................................................................................28 6. Proposed Infrastructure ................................................................. -

Health and Family Welfare Department

GOVERNMENT OF KARNATAKA HEALTH AND FAMILY WELFARE DEPARTMENT ANNUAL REPORT (2018-2019) HEALTH AND FAMILY WELFARE DEPARTMENT ANNUAL REPORT (2018-2019) INDEX PART-I HEALTH AND FAMILY WELFARE DEPARTMENT Sl.No. Subject Page No. 1.1 Organization and Functions of the Department 1-2 1.2 Important National & State Health Programmes 2-44 1.2.1 Immunization Programme 2-6 1.2.2 National Leprosy Eradication Programme 6-9 1.2.3 Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme 9-14 1.2.4 National Programme for Control of Blindness 14-19 1.2.5 Karnataka State AIDS Prevention Society 20-28 1.2.6 National Vector Borne Diseases Control Programme 28-30 1.2.7 Communicable Diseases (CMD) 30-31 1.2.8 Reproductive and Child Health Programme 32-37 1.2.9 RCH Portal 37 1.2.10 Mother Health 38 1.2.11 Emergency Management and Research Institute (EMRI): 38-43 Pre-Conception and Pre-natal Diagnostic Techniques 1.2.12 Programmes (PC & PNDT) 43-44 1.3 School Health Programme 45-48 1.4 SAKALA Guaranteed services rendered 48-49 1.5 Health Indicators 49 1.6 Health Services 49-51 1.7 National Urban Health Mission 51-58 1.7.1 Quality Assurance 58-65 National Programme for Prevention and Control of 1.7.2 Fluorosis (NPPCF) 65-67 1.8 Citizen Friendly Facilities 68-69 1.9 Regulation of Private Medical Establishments 69-71 1.10 Health Education and Training 71-72 1.11 Mental Health Programme 72-76 Information, Education & Communication (IEC) 1.12 programme 76-77 1.13 State Health Transport Organization 77 1.14 Integrated Disease Surveillance Project (IDSP) 77-79 1.15 Nutrition -

Research Paper Impact Factor

Research Paper IJBARR Impact Factor: 5.471 E- ISSN -2347-856X Peer Reviewed & Indexed Journal ISSN -2348-0653 OMBUDSMAN - A COMPARATIVE STUDY Katha Mathur Research Scholar, Manipal University, Jaipur, Dehmi Kalam, Rajasthan. Abstract Ombudsmanship is a concept of independent, easily accessible and soft control of public administration related to principle of democracy, rule of law and the good administration. The purpose of the present study is basically a legal comparison of different countries but more focus on some selected Indian cities and analyzing them. The focus of this study is to exhibit the appearances of Ombudsman institutions in different legal orders. Such study is necessary to find out the comparative status of legal working and acceptance denial of work environment. As we see, states and country are facing problems in making the concept a big success. The researcher has used a Doctrinal approach to this study by reading different articles, annual reports of states, research paper and books and would a comparative study. Based on the above, critical examination of ombudsman at many levels is done as a humble attempt to evolve and expand the role of it. As this study will highlight the importance and would suggest the awareness of Ombudsman. The Whole idea behind it is to come up with such points which can contribute a little in filling the ambiguity. This we know that there are some lacunas because of which we fail to achieve the success. So aptly studying on the topic would help to come with some good suggestions and conclusions. Introduction An ombudsman is an official person, usually appointed by the government or by the parliament but, who is charged with representing the interests of the public by investigating and addressing complaints of maladministration violation of rights. -

Shake Hands and Make up 0

NEWSBEAT Shake hands and make up Chief minister Ramakrishna Hegde and the dissidents, led by H. D. Deve Gowda, have called a truce. But, given the belligerence of both sides, how long will it last? ast week, Sunday wondered In fact, there is a persistent suspicion whether Ajit Singh, the new that in spite of the Express'reference to young president of the Janata central government sources, the trans Party would accept Ramak cript came from Bangalore. Who stands rishna Hegde’s resignation. to gain the most from exposing a nexus This week, the answer is in. Yet anotherbetween Ajit Singh and Deve Gowda ofL Hegde’s resignation dramas has ask the cynics. Obviously, it is the chief drawn curtains prematurely. It was up minister. staged by a bigger story: the transcript The chief minister, of course, loudly of the phone conversation between Ajit denied his involvement. In fact, he tried Singh and Janata rebel leader H.D. Deve to give yet another tape episode Gowda, that appeared in Ihe Indian the political. mileage he had ex Express on 10 July. tracted from the Veerappa Moily -Byre The timing was devastating enough to Gowda tapes. This time hewasmuch look suspiciously like a deliberate plant. more subdued. But he is still the injured It came on the eve of Hegde’s departure innocent. “You know, even my phone is to Delhi for the crucial Janata Parliamen tapped, ” he said in Bangalore. So will he Hegde being welcomed by loyalists on his tary Board meeting. Worse. It was not lodge a protest with the central return from Delhi: triumphant carried along with the full text of government? “I have done it so many Hegde’s conditional resignation to Ajit times, what is the use?” he replied. -

Cm of Karnataka List Pdf

Cm of karnataka list pdf Continue CHIEF MINISTERS OF KARNATAKA Since 1947 SL.NO. Date from date to 1. Sri K.CHENGALARAY REDDY 25-10-1947 30-03-1952 2. Sri K.HANUMANTAYA 30-03-1952 19-08-1956 3. Sri KADIDAL MANJAPPA 19-08-1956 31-10-1956 4. Sri S.NIALINGAPPA 01-11-1956 16-05-1958 5. Sri B.D. JATTI 16-05-1958 09-03-1962 6. Sri S.R.Kanthi 14-03-1962 20-06-1962 7. Sri S.NIALINGAPPA 21-06-1962 28-05-1968 8. Shri VERENDRA PATIL 29-05-1968 18-03-1971 9. PRESIDENTIAL RULE 19-03-1971 20-03-1972 10. Sri D.DEVRAJ URS 20-03-1972 31-12-1977 11. RULE PRESIDENTS 31-12-1977 28-02-1978 12. Sri D.DEVARAJ URS 28-02-1978 07-01-1980 13. Sri R.GUNDU RAO 12-01-1980 06-01- 1983 14. Sri RAMAKRISHNA HEGDE 10-01-1983 29-12-1984 15. Sri RAMAKRISHNA HEGDE 08-03-1985 13-02-1986 16. Sri RAMAKRISHNA HEGDE 16-02-1986 10-08-1988 17. Sri S.R.BOOMMAI 13-08-1988 21-04-1989 18. PRESIDENTIAL RULE 21-04-1989 30-11-1989 19. Shri VERENDRA PATIL 30-11-1989 10-10-1990 20. PRESIDENTIAL RULE 10-10-1990 17-10-1990 21. Sri S.BANGARAPPA 17-10-1990 19-11-1992 22. Sri VEERAPPA MOILY 19-11-1992 11-12-1994 23. Sri H.D. DEVEGOVDA 11-12-1994 31-05-1996 24. Sri J.H.PATEL 31-05-1996 07-10-1999 25. -

Mandya District Human Development Report 2014

MANDYA DISTRICT HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2014 Mandya Zilla Panchayat and Planning, Programme Monitoring and Statistics Department Government of Karnataka COPY RIGHTS Mandya District Human Development Report 2014 Copyright : Planning, Programme Monitoring and Statistics Department Government of Karnataka Published by : Mandya Zilla Panchayat, Government of Karnataka First Published : 2014 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form by any means without the prior permission by Zilla Panchayat and Planning, Programme Monitoring and Statistics Department, Government of Karnataka Printed by : KAMAL IMPRESSION # 54, Sri Beereshwara Trust Camplex, SJCE Road, T.K. Layout, Mysore - 570023. Mobile : 9886789747 While every care has been taken to reproduce the accurate data, oversights / errors may occur. If found convey it to the CEO, Zilla Panchayat and Planning, Programme Monitoring and Statistics Department, Government of Karnataka VIDHANA SOUDHA BENGALURU- 560 001 CM/PS/234/2014 Date : 27-10-2014 SIDDARAMAIAH CHIEF MINISTER MESSAGE I am delighted to learn that the Department of Planning, Programme Monitoring and Statistics is bringing out District Human Development Reports for all the 30 Districts of State, simultaneously. Karnataka is consistently striving to improve human development parameters in education, nutrition and health through many initiatives and well-conceived programmes. However, it is still a matter of concern that certain pockets of the State have not shown as much improvement as desried in the human development parameters. Human resource is the real wealth of any State. Sustainable growth and advancement is not feasible without human development. It is expected that these reports will throw light on the unique development challenges within each district, and would provide necessary pointers for planners and policy makers to address these challenges. -

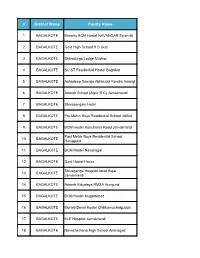

District Name Facilty Name

# District Name Facilty Name 1 BAGALKOTE Minority BCM Hostel NAVANGAR Sctor-46 2 BAGALKOTE Govt High School H S Gutti 3 BAGALKOTE Shivadurga Lodge Mudhol 4 BAGALKOTE SC ST Residential Hostel Bagalkot 5 BAGALKOTE Ashadeep Samaja Abhiruddi Kendra Asangi 6 BAGALKOTE Adarsh School (Algur R C) Jamakhandi 7 BAGALKOTE Shivasangam Hotel 8 BAGALKOTE Pre Metric Boys Residential School Jalihal 9 BAGALKOTE BCM Hostel Kunchanur Road Jamakhandi Post Metric Boys Residential School 10 BAGALKOTE Hunagund 11 BAGALKOTE BCM Hostel Navanagar 12 BAGALKOTE Govt Hostel Hosur Shivaganga Hospital Jolad Bajar 13 BAGALKOTE Jamakhandi 14 BAGALKOTE Adarsh Vidyalaya RMSA Hungund 15 BAGALKOTE BCM Hostel Mugalakhod 16 BAGALKOTE Morarji Desai Hostel Chikkamuchalgudda 17 BAGALKOTE KLE Hospital Jamakhandi 18 BAGALKOTE Navachethana High School Aminagad 19 BAGALKOTE Omkar Lodge Mudhol 20 BALLARI ROCK REGENCY 21 BALLARI MAYURA HOTEL 22 BALLARI KRK RESIDENCY 23 BALLARI VISHNU PRIYA HOTEL 24 BALLARI VIDYA RESIDENCY 25 BALLARI MD SCHOOL 26 BALLARI SIDDHARTH HOTEL 27 BELAGAVI Murarrji Desai School Katkol 28 BELAGAVI Hotel Rajdhani Sankeshwar 29 BELAGAVI New Lodge 30 BELAGAVI CHC Kabbur 31 BELAGAVI Pavan Hotel 32 BELAGAVI CHC Mudalagi 33 BELAGAVI Megha Lodge 34 BELAGAVI APMC Gokak Hostel METRIC NANTAR BALAKIYAR VIDYARTHI 35 BELAGAVI NILAY 36 BELAGAVI Morarji Desai High School Hulikatti 37 BELAGAVI S K LODGE 38 BELAGAVI Classic Lodge Kittur Rani Chennamma Girls Residential 39 BELAGAVI School, Chamakeri Maddi 40 BELAGAVI Priti Lodge Kudachi 41 BELAGAVI Murarji Desai High School Savadatti -

1995-96 and 1996- Postel Life Insurance Scheme 2988. SHRI

Written Answers 1 .DECEMBER 12. 1996 04 Written Answers (c) if not, the reasons therefor? (b) No, Sir. THE MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF (c) and (d). Do not arise. RAILWAYS (SHRI SATPAL MAHARAJ) (a) No, Sir. [Translation] (b) Does not arise. (c) Due to operational and resource constraints. Microwave Towers [Translation] 2987 SHRI THAWAR CHAND GEHLOT Will the Minister of COMMUNICATIONS be pleased to state : Construction ofBridge over River Ganga (a) the number of Microwave Towers targated to be set-up in the country during the year 1995-96 and 1996- 2990. SHRI RAMENDRA KUMAR : Will the Minister 97 for providing telephone facilities, State-wise; of RAILWAYS be pleased to state (b) the details of progress achieved upto October, (a) whether there is any proposal to construct a 1906 against above target State-wise; and bridge over river Ganges with a view to link Khagaria and Munger towns; and (c) whether the Government are facing financial crisis in achieving the said target? (b) if so, the details thereof alongwith the time by which construction work is likely to be started and THE MINISTER OF COMMUNICATIONS (SHRI BENI completed? PRASAD VERMA) : (a) to (c). The information is being collected and will be laid on the Table of the House. THE MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF RAILWAYS (SHRI SATPAL MAHARAJ) : (a) No, Sir. [E nglish] (b) Does not arise. Postel Life Insurance Scheme Railway Tracks between Virar and Dahanu 2988. SHRI VIJAY KUMAR KHANDELWAL : Will the Minister of COMMUNICATIONS be pleased to state: 2991. SHRI SURESH PRABHU -

3. Modern Indian History

UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION IV SEMESTER B.A HISTORY: COMPLEMENTARY MODERN INDIAN HISTORY (1857 TO THE PRESENT DAY: HIS4C01 SELECTED THEMES IN CONTEMPORARY INDIA (2014 Admission onwards) Multiple-Choice Questions and Answers Prepared by Dr.N.PADMANABHAN Associate Professor&Head P.G.Department of History C.A.S.College, Madayi P.O.Payangadi-RS-670358 Dt.Kannur-Kerala 1. The Constitution of ....................is the largest written liberal democratic constitution of the world. 1 a) India b) America c) Pakistan d) Afghanistan 2. The Constitution of ...................provides for a mixture of federalism and Unitarianism, and flexibility and with rigidity. a) Afghanistan b) America c) Pakistan d) India 3. since its inauguration on 26th January.............. , the Constitution India has been successfully guiding the path and progress of India. a)1905 b)1915 c)1930 d) 1950 4. Indian Constitution consists of ................ Articles divided into 22 Parts with 12 Schedules and 94 constitutional amendments. a)295 b)305 c)388 d) 395 5.The Constitution of India indeed much bigger than the US Constitution which has only 7 Articles and the ..................Constitution with its 89 Articles. a) French b) Dutch c) Pakistan d)Afghanistan 6. The constitution of India became fully operational with effect from 26th January.......................... a)1905 b)1935 c)1947 d) 1950 7. Although, right from the beginning the Indian Constitution fully reflected the spirit of democratic socialism, it was only in ................. that the Preamble was amended to include the term ‘Socialism’. a)1936 b)1946 c)1956 d) 1976 8.India has an elected head of state (President of India) who wields power for a fixed term of .................. -

THE KARNATAKA LOKAYUKTA ACT, 1984 Sections

THE KARNATAKA LOKAYUKTA ACT, 1984 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS Sections: 1. Short title and commencement. 2. Definitions. 3. Appointment of Lokayukta and Upalokayukta. 4. Lokayukta or Upalokayukta not to hold any other office. 5. Term of office and other conditions of service of Lokayukta and Upalokayukta. 6. Removal of Lokayukta or Upalokayukta. 7. Matters which may be investigated by the Lokayukta and an Upalokayukta. 8. Matters not subject to investigation. 9. Provisions relating to complaints and investigations. 10. Issue of search warrant, etc. 11. Evidence. 12. Reports of Lokayukta , etc. 13. Public servant to vacate office if directed by Lokayukta, etc. 14. Initiation of prosecution. 15. Staff of Lokayukta, etc. 16. Secrecy of information. 17. Intentional insult or interruption to or bringing into disrepute the Lokayukta or Upalokayukta. 17A. Power to punish for contempt. 18. Protection. 19. Conferment of additional functions on Upalokyukta. 20. Prosecution for false complaint. 21. Power to delegate. 22. Public servants to submit property statements. 23. Power to make rules. 24. Removal of doubts. 25. Removal of difficulties. 26. Repeal and savings. FIRST SCHEDULE SECOND SCHEDULE ***** STATEMENT OF OBJECTS AND REASONS I Act 4 of 1985.- The administrative reforms commission had recommended the setting up of the institution of Lokayukta for the purpose of improving the standards of public administration, by looking into complaints against administrative actions, including cases of corruption, favouritism and official indiscipline in administration machinery. One of the election promises in the election manifesto of the Janatha Party was the setting up of the institution of the Lokayukta. The Bill provides for the appointment of a Lokayukta and one or more Upalokayuktas to investigate and report on allegations or grievances relating to the conduct of public servants.