Introduction to Amaranth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Probable Use of Genus Amaranthus As Feed Material for Monogastric Animals

animals Review The Probable Use of Genus amaranthus as Feed Material for Monogastric Animals Tlou Grace Manyelo 1,2 , Nthabiseng Amenda Sebola 1 , Elsabe Janse van Rensburg 1 and Monnye Mabelebele 1,* 1 Department of Agriculture and Animal Health, College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences, University of South Africa, Florida 1710, South Africa; [email protected] (T.G.M.); [email protected] (N.A.S.); [email protected] (E.J.v.R.) 2 Department of Agricultural Economics and Animal Production, University of Limpopo, Sovenga 0727, South Africa * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +27-11-471-3983 Received: 13 July 2020; Accepted: 5 August 2020; Published: 26 August 2020 Simple Summary: In monogastric production, feeds account for about 50–70% of the total costs. Protein ingredients are one of the most expensive inputs even though they are not included in large quantities as compared to cereals. Monogastric animal industries are faced with a major problem of limited protein sources, moreover, the competition for plant materials is expected to further increase feed prices. Therefore, to tackle this problem, interventions are required to find alternative and cost-effective protein sources. One identified crop that meets these requirements is amaranth. Studies have shown the potential and contribution that amaranth has as an alternative ingredient in diets for monogastric animals. Therefore, the main purpose of this review is to provide a detailed understanding of the potential use of amaranth as feed for monogastric animals, and further indicate processing techniques are suitable to improve the utilization of grain amaranth and leaves. -

The Amaranth (Amaranthus Hypochondriacus) Genome: Genome, Transcriptome and Physical Map Assembly

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2015-06-01 The Amaranth (Amaranthus Hypochondriacus) Genome: Genome, Transcriptome and Physical Map Assembly Jared William Clouse Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Plant Sciences Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Clouse, Jared William, "The Amaranth (Amaranthus Hypochondriacus) Genome: Genome, Transcriptome and Physical Map Assembly" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 5916. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/5916 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Amaranth (Amaranthus hypochondriacus) Genome: Genome, Transcriptome and Physical Map Assembly Jared William Clouse A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science P. Jeffery Maughan, Chair Eric N. Jellen Joshua A. Udall Department of Plant and Wildlife Sciences Brigham Young University June 2015 Copyright © 2015 Jared William Clouse All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The Amaranth (Amaranthus Hypochondriacus) Genome: Genome, Transcriptome and Physical Map Assembly Jared William Clouse Department of Plant and Wildlife Sciences, BYU Master of Science Amaranthus hypochondriacus is an emerging pseudo-cereal native to the New World which has garnered increased attention in recent years due to its nutritional quality, in particular its seed protein, and more specifically its high levels of the essential amino acid lysine. It belongs to the Amaranthaceae family, is an ancient paleotetraploid that shows amphidiploid inheritance (2n=32), and has an estimated genome size of 466 Mb. -

Gluten-Free Grains

Gluten-Free Grains Amaranth Updated February 2021 Buckwheat The gluten-free diet requires total avoidance of the grains wheat, barley, rye and all varieties and hybrids of these grains, such as spelt. However, there are many wonderful gluten-free grains* to enjoy. Cornmeal, Amaranth Polenta, Grits, Once the sacred food of the Aztecs, amaranth is high in protein, calcium, iron, and fiber. Toasting this tiny grain before cooking brings out its nutty flavor. Hominy Makes a delicious, creamy hot breakfast cereal. Serve with fruit of choice on top and/or a touch of maple syrup. Millet Rice Rice comes in many varieties: short grain, long grain, jasmine and basmati to name a Oats few. Long grain rice tends to be fluffier while short grain rice is stickier. Rice also comes in various colors: black, purple, brown, and red. These colorful un-refined rices contribute more nutritional benefits than does refined white rice and have subtly unique flavors and Quinoa textures too. Wild rice is another different and delicious option. Versatile rice leftovers can go in many directions. Add to salads or sautéed vegetables; Rice make rice pancakes or rice pudding; season and use as filling for baked green peppers or winter squash. Sorghum Buckwheat Despite the name, buckwheat is a gluten-free member of the rhubarb family. Roasted buckwheat is called kasha. Buckwheat is high in B Vitamins, fiber, iron, magnesium, Teff phosphorous and zinc. Buckwheat has an earthy, nutty, slightly bitter taste. Experiment with using the cooked grain (buckwheat “groats”, or “kasha” which is the toasted version) as you would rice. -

The Best Indian Diet Plan for Weight Loss

The Best Indian Diet Plan for Weight Loss Indian cuisine is known for its vibrant spices, fresh herbs and wide variety of rich flavors. Though diets and preferences vary throughout India, most people follow a primarily plant-based diet. Around 80% of the Indian population practices Hinduism, a religion that promotes a vegetarian or lacto-vegetarian diet. The traditional Indian diet emphasizes a high intake of plant foods like vegetables, lentils and fruits, as well as a low consumption of meat. However, obesity is a rising issue in the Indian population. With the growing availability of processed foods, India has seen a surge in obesity and obesity-related chronic diseases like heart disease and diabetes . This document explains how to follow a healthy Indian diet that can promote weight loss. It includes suggestions about which foods to eat and avoid and a sample menu for one week. A Healthy Traditional Indian Diet Traditional plant-based Indian diets focus on fresh, whole ingredients — ideal foods to promote optimal health. Why Eat a Plant-Based Indian Diet? Plant-based diets have been associated with many health benefits, including a lower risk of heart disease, diabetes and certain cancers such as breast and colon cancer. Additionally, the Indian diet, in particular, has been linked to a reduced risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Researchers believe this is due to the low consumption of meat and emphasis on vegetables and fruits. Following a healthy plant-based Indian diet may not only help decrease the risk of chronic disease, but it can also encourage weight loss. -

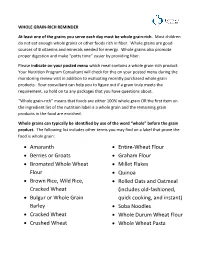

• Amaranth • Berries Or Groats • Bromated Whole Wheat Flour

WHOLE GRAIN-RICH REMINDER At least one of the grains you serve each day must be whole grain-rich. Most children do not eat enough whole grains or other foods rich in fiber. Whole grains are good sources of B vitamins and minerals needed for energy. Whole grains also promote proper digestion and make “potty time” easier by providing fiber. Please indicate on your posted menu which meal contains a whole grain-rich product. Your Nutrition Program Consultant will check for this on your posted menu during the monitoring review visit in addition to evaluating recently purchased whole grain products. Your consultant can help you to figure out if a grain truly meets the requirement, so hold on to any packages that you have questions about. “Whole grain-rich” means that foods are either 100% whole grain OR the first item on the ingredient list of the nutrition label is a whole grain and the remaining grain products in the food are enriched. Whole grains can typically be identified by use of the word “whole” before the grain product. The following list includes other terms you may find on a label that prove the food is whole grain: Amaranth Entire-Wheat Flour Berries or Groats Graham Flour Bromated Whole Wheat Millet Flakes Flour Quinoa Brown Rice, Wild Rice, Rolled Oats and Oatmeal Cracked Wheat (includes old-fashioned, Bulgur or Whole Grain quick cooking, and instant) Barley Soba Noodles Cracked Wheat Whole Durum Wheat Flour Crushed Wheat Whole Wheat Pasta . -

Grain Amaranths Amaranthus Spp. (Amaranthaceae)

Grain Amaranths Amaranthus spp. (Amaranthaceae) Klaus Ammann and Jonathan Gressel Manuscript 17. October 2007 Introduction Amaranthus could be a valuable alternative crop due to its high nutritional content, the many desirable traits expressed by the grain amaranths – and the unexplored potential of the wild relatives. Unlike the traditional monocot grains, the grain amaranths possess lysine in nutritionally significant levels. In addition, specific varieties of grain amaranths tolerate drought and heat, and, as a result, lessen the demand for costly irrigation. Peruvian varieties of Amaranthus caudatus have are known for their resistance to damping off and to root rot. Based upon phylogenecic studies (Lanoue et al., 1996) a number of wild species closely related to cultivated Amaranths should be explored for breeding purposes: Amaranthus floridanus and A. pumilus for salt tolerance, A. powellii and A. fimbriatus for drought resistance, and A. hybridus , A. quitensis, and A. retroflexus for pest, viral and bacterial resistance. Not only would these wild species be valuable for breeding with the cultivated Amaranths, but they would also be favourable target species to explore useful genes for other crop traits. Origin and use Amaranths have a long tradition in the New World, where they have been grown as pseudo- cereals by pre-Columbian civilizations on thousands of hectares. In Mesoamerica, amaranth developed as an important ritual and cash crop. They were grown as the principal grain crop by the Aztecs 5,000 to 7,000 years ago, until to the disruption of their culture(s) by the Spanish Conquistadors. The reasons of this decline is still unclear, since the Aztecs relied on the amaranths as an important staple. -

Ozone Dose-Response Relationships for Tropical Crops Reveal Potential Threat to Legume and Wheat Production, but Not to Millets

Scientific African 0 0 0 (2020) e00482 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Scientific African journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/sciaf Ozone dose-response relationships for tropical crops reveal potential threat to legume and wheat production, but not to millets ∗ Felicity Hayes , Harry Harmens, Katrina Sharps, Alan Radbourne UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, Environment Centre Wales, Deiniol Road, Bangor, Gwynedd, LL57 2UW, UK a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: The tropical-grown crops common bean ( Phaseolus vulgaris ), mung bean ( Vigna radi- Received 21 February 2020 ate ), cowpea ( Vigna unguiculata ), pearl millet ( Pennisetum glaucum ), finger millet ( Eleusine Revised 9 July 2020 coracana ), amaranth ( Amaranthus hypochonriacus ), sorghum ( Sorghum bicolour ) and wheat Accepted 10 July 2020 ( Triticum aestivum ) were exposed to different concentrations of the air pollutant ozone in Available online xxx experimental Solardome facilities. The plants were exposed to ozone treatments for be- Keywords: tween one and four months, depending on the species. There was a large decrease in yield Pollution of protein-rich beans and cowpeas with increasing ozone exposure, partly attributable to Ozone a reduction in individual bean/pea weight. Size of individual grains was also reduced with Food security increasing ozone for African varieties of wheat. In contrast, the yield of amaranth, pearl Thousand grain weight millet and finger millet (all C 4 species) was not sensitive to increasing ozone concentra- Protein content tions and there was some evidence of an increase in weight of individual seedheads with Cereal increasing ozone for finger millet. -

Molecular Advances for Improving Nutrient Bioavailability

REVIEW published: 27 February 2020 doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.00049 Healthy and Resilient Cereals and Pseudo-Cereals for Marginal Agriculture: Molecular Advances for Improving Nutrient Bioavailability † † Juan Pablo Rodríguez , Hifzur Rahman , Sumitha Thushar and Rakesh K. Singh* Crop Diversification and Genetics Program, International Center for Biosaline Agriculture, Dubai, United Arab Emirates With the ever-increasing world population, an extra 1.5 billion mouths need to be fed by Edited by: 2050 with continuously dwindling arable land. Hence, it is imperative that extra food come Felipe Klein Ricachenevsky, from the marginal lands that are expected to be unsuitable for growing major staple crops Universidade Federal de under the adverse climate change scenario. Crop diversity provides right alternatives for Santa Maria, Brazil marginal environments to improve food, feed, and nutritional security. Well-adapted and Reviewed by: fi Joel B. Mason, climate-resilient crops will be the best t for such a scenario to produce seed and Tufts University School of Medicine, biomass. The minor millets are known for their high nutritional profile and better resilience United States for several abiotic stresses that make them the suitable crops for arid and salt-affected Scott Aleksander Sinclair, Ruhr University soils and poor-quality waters. Finger millet (Eleucine coracana) and foxtail millet (Setaria Bochum, Germany italica), also considered as orphan crops, are highly tolerant grass crop species that grow *Correspondence: well in marginal and degraded lands of Africa and Asia with better nutritional profile. Rakesh K. Singh [email protected]; Another category of grains, called pseudo-cereals, is considered as rich foods because of [email protected] their protein quality and content, high mineral content, and healthy and balance food quality. -

Early Cultivation Spanish Colonization Research and Revival

Amaranth was first cultivated around 8,000 years ago. Early Cultivation Amaranth was first cultivated for its protein and nutrient rich seeds and edible leaves around 8000 years ago in Mexico. It was a major food crop of the pre-Hispanic Aztecs, who called it huautli. It likely supplied up to 80% of their energy consumption and, being so important, it was one of the required tributes paid to their rulers. Aztec man harvesting amaranth Amaranth was also integral to Aztec religious ceremonies. For example, to pay homage to their gods, statues were made with a dough called tzoalli of popped amaranth seeds mixed with agave syrup. These idols were worshipped, then broken apart and distributed to the faithful to eat. Leaves also had their place in ceremonial meals. They were used in the tamales offered to the dead at the feast of Huauquiltamalcualitztli, meaning “the meal of the amaranth tamales.” Spanish Colonization Upon defeating the Aztecs in 1521, Spanish conquerors destroyed the amaranth Research and Revival crops and banned its further cultivation in order to subdue the population, Amaranth never regained its status as a dominant restrict their customs, and convert them to Christianity. It couldn’t be wiped out staple crop, but it is still grown and featured in completely, however, as wild populations persisted and people in remote areas Mexican and Central American cuisine today. A continued to grow it. typical Mexican confection of popped amaranth seeds mixed with sugar syrup or honey, called Alegría or “Joy,” harkens back to ancient times. Native South American amaranth was grown and consumed by the ancient Incas of Peru. -

Properties of Amaranth Flour with Functional Oat Products

Journal of Food Research; Vol. 3, No. 6; 2014 ISSN 1927-0887 E-ISSN 1927-0895 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Properties of Amaranth Flour With Functional Oat Products George E. Inglett1, Diejun Chen1 & Sean Liu1 1 Functional Foods Research Unit, National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research, USDA, Agricultural Research Service, 1815 N University Street, Peoria, IL 61604, USA Mention of trade names or commercial products in this publication is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Correspondence: George E. Inglett, USDA, Agricultural Research Service, National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research, Functional Foods Research Unit, USA. Tel: 1-309-681-6363; Fax: 1-309-681-6685. E-mail: [email protected] Received: June 12, 2014 Accepted: July 9, 2014 Online Published: July 15, 2014 doi:10.5539/jfr.v3n6p1 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/jfr.v3n6p1 Abstract Amaranth flour (Salvia hispanica L.), gluten free and rich in essential amino acids, was composited with oat functional products containing β-glucan known for lowering blood cholesterol and preventing heart disease. The objective of this research was to study the pasting and rheological properties of amaranth flour interacted with functional oat products using Rapid Visco Analyzer followed by an advanced rheometer. The initial peak viscosities of amaranth-Nutrim (oat bran hydrocolloids) and amaranth-OBC (oat bran concentrate) composites were increased with higher Nutrim and OBC contents. The final pasting viscosities of amaranth-OBC composites were increased significantly with higher OBC contents while amaranth-Nutrim composites showed colloidal gel properties similar to Nutrim. -

VANCOUVER NATUROPATHIC CLINIC Candida Diet

VANCOUVER NATUROPATHIC CLINIC 1308 West 8th Ave, Vancouver, BC, V6H 4A6 Tel: (604) 738-2111 Fax: (604) 738-5515 Candida Diet Eat as much as you want: Vegetables As a general rule, the darker green or brightly coloured veggies contain the most nutrients and antioxidant activity. They can be eaten steamed or lightly sautéed. All veggies are okay. Artichoke Cucumbers Parsley Asparagus Eggplant Parsnip Avocadoes Green pepper Radishes Beets Swiss chard Soy beans Bok choy Spinach String beans Broccoli Mustard greens Squash Brussel sprouts Beet greens Tomatoes Cabbage Collard greens Turnips Carrots Kale Okra Cauliflower Garlic Yam Celery Lettuce – dark green Zucchini Chives Onions Whole grains Eliminate refined grain products such as white breads, bagels, muffins, crackers. Include plenty of whole grains. Whole grain pasta is available at many grocery stores. Avoid all yeast containing products (flat breads are OK) Grains Buckwheat Potato Amaranth Oats Legume Brown rice Rye Jasmine rice Spelt Basmati rice Pasta Coarse cornmeal Flours Quinoa Millet Arrowroot Rice Quinoa Amaranth Amaranth Wild rice Brown Rice Soy Oats Garbanzo (Chick pea) Oat groats Soybean VANCOUVER NATUROPATHIC CLINIC 1308 West 8th Ave, Vancouver, BC, V6H 4A6 Tel: (604) 738-2111 Fax: (604) 738-5515 Protein Choosing organic sources of protein is important. Animal sources: Seafood: Plant-based proteins: Chicken Salmon Tofu Turkey Halibut Soybeans Bison Cod Lentils Lamb Sardines Split peas Wild game No tinned fish in oil Tempeh Limit beef and eggs Textured-soy products Pinto -

WHOLE GRAINS a to Z

WHOLE GRAINS A TO Z AMARANTH (Amaranthus cruentus) Amaranth was a staple of Aztec culture, until Cortez decreed that anyone growing the crop would be put to death. Seeds were smuggled to Asia, where local dialects referred to amaranth as “seed sent by God” as a tribute to its taste and sustenance. Amaranth kernels are tiny and resemble brown caviar when cooked. Today amaranth is making its way back, thanks to a lively, peppery taste and a higher level of protein (13.56% ) than most other grains. In South America, it is often sold on the streets, popped like corn. Amaranth has no gluten, so it must be mixed with wheat to make leavened breads. It is popular in cereals, breads, muffins, crackers and pancakes. Health bonus: Amaranth is a source of complete protein; its protein contains lysine, an amino acid missing or negligible in many grains. BARLEY (Hordum vulgare) Barley is one of the oldest cultivated grains. Egyptians buried mummies with necklaces of barley, and centuries later Edward I of England standardized the inch as equal to “three barley seeds.” It is a highly-adaptable crop, growing north of the Arctic Circle and as far south as Ethiopia. Barley has a very tough hull, difficult to remove without losing some bran. Pearled barley is not a whole grain (but is still high in fiber). Look for hulled barley or one of the new varieties of hull-less barley starting to be available. Lightly pearled barley is not technically a whole grain (as small amounts of the bran are missing)—but it’s full of fiber and much healthier than a fully-refined grain.