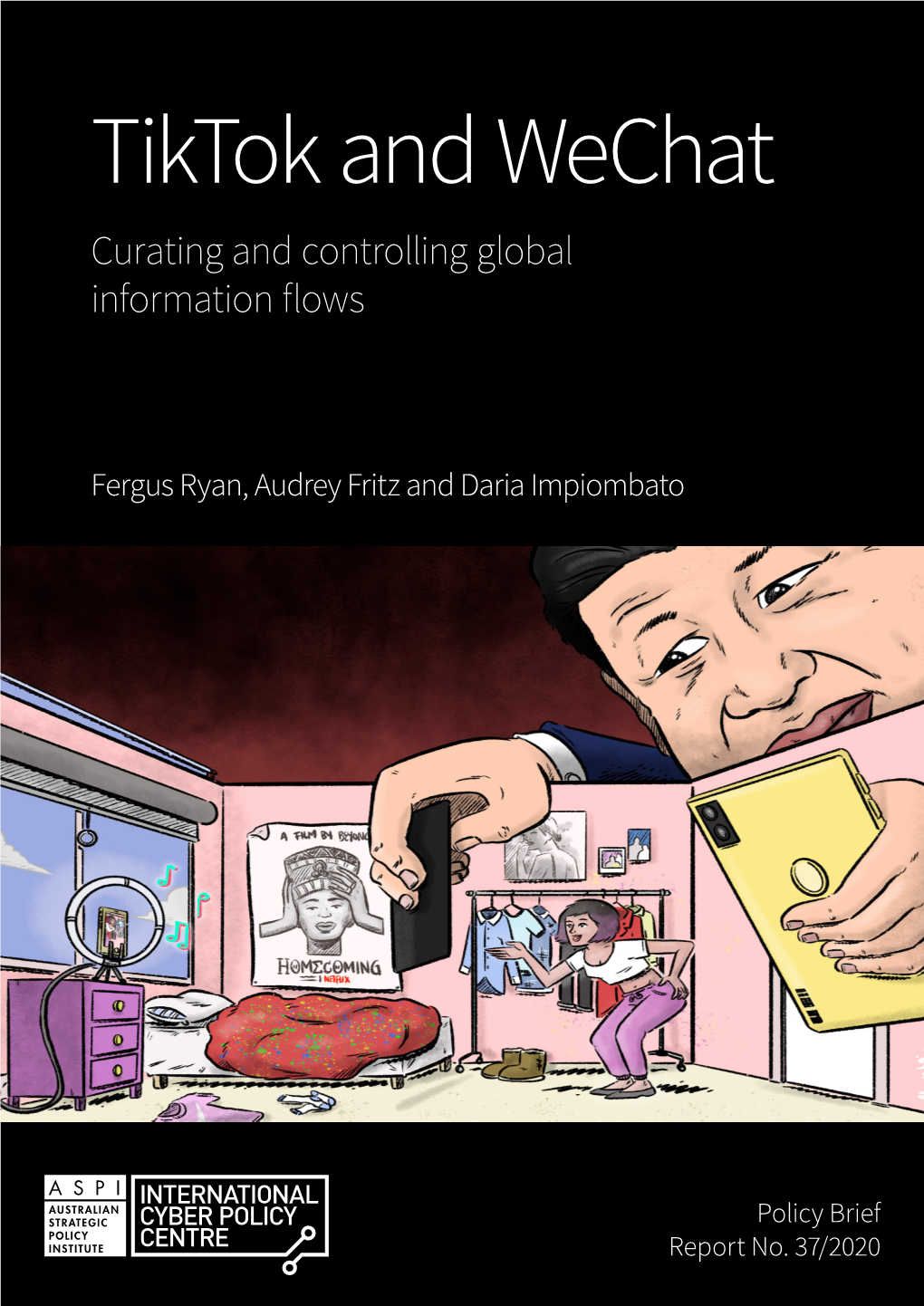

Tiktok and Wechat Curating and Controlling Global Information Flows

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

American Evangelicalism and the Uyghur Crisis: a Call to Interfaith Advocacy

Blay| 1 American Evangelicalism and the Uyghur Crisis: A Call to Interfaith Advocacy Joshua Blay Northwest University International Community Development Program Author’s Notes Aspects of this paper were written for the following classes: Practicum IV, Practicum V, Fieldwork, Leadership, Social and Environmental Justice, and Peacemaking. Disclaimer: All names of Uyghurs within this thesis have been alerted to protect their identities. Blay| 2 I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 4 II. THE UYGHUR CRISIS .................................................................................................................................. 5 A. A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE UYGHUR PEOPLE ............................................................................................................. 6 i. Why Commit Cultural Genocide? .................................................................................................................... 7 ii. My Research and the Uyghur Crisis .............................................................................................................. 9 III. LOVE GOD AND LOVE NEIGHBOR ....................................................................................................... 11 A. LOVING GOD AND NEIGHBOR THROUGH RESOURCES, PRIVILEGE, AND POWER ...................................................... 14 i. Resources ....................................................................................................................................................... -

New Media in New China

NEW MEDIA IN NEW CHINA: AN ANALYSIS OF THE DEMOCRATIZING EFFECT OF THE INTERNET __________________ A University Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, East Bay __________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in Communication __________________ By Chaoya Sun June 2013 Copyright © 2013 by Chaoya Sun ii NEW MEOlA IN NEW CHINA: AN ANALYSIS OF THE DEMOCRATIlING EFFECT OF THE INTERNET By Chaoya Sun III Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 PART 1 NEW MEDIA PROMOTE DEMOCRACY ................................................... 9 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 9 THE COMMUNICATION THEORY OF HAROLD INNIS ........................................ 10 NEW MEDIA PUSH ON DEMOCRACY .................................................................... 13 Offering users the right to choose information freely ............................................... 13 Making free-thinking and free-speech available ....................................................... 14 Providing users more participatory rights ................................................................. 15 THE FUTURE OF DEMOCRACY IN THE CONTEXT OF NEW MEDIA ................ 16 PART 2 2008 IN RETROSPECT: FRAGILE CHINESE MEDIA UNDER THE SHADOW OF CHINA’S POLITICS ........................................................................... -

Targeting the Anti- Extradition Bill Movement

TARGETING THE ANTI- EXTRADITION BILL MOVEMENT China’s Hong Kong Messaging Proliferates on Social Media The Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab) is a start-up incubated at the Atlantic Council and leading hub of digital forensic analysts whose mission is to identify, expose, and explain disinformation where and when it occurs. The DFRLab promotes the idea of objective truth as a foundation of governance to protect democratic institutions and norms from those who would undermine them. The Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security works to develop sustainable, nonpartisan strategies to address the most important security challenges facing the United States and the world. The Center honors General Brent Scowcroft’s legacy of service and embodies his ethos of nonpartisan commitment to the cause of security, support for US leadership in cooperation with allies and partners, and dedication to the mentorship of the next generation of leaders. The Scowcroft Center’s Asia Security Initiative promotes forward-looking strategies and con-structive solutions for the most pressing issues affecting the Indo- Pacific region, particularly the rise of China, in order to enhance cooperation between the United States and its regional allies and partners. COVER PHOTO (BACKGROUND): “Hong Kong Waterfront,” by Thom Masat (@tomterifx), Unsplash. Published on June 6, 2018. https://unsplash.com/photos/t_YWqXcK5lw This report is written and published in accordance with the Atlantic Council Policy on Intellectual Independence. The authors are solely responsible for its analysis and recommendations. The Atlantic Council and its donors do not determine, nor do they necessarily endorse or advocate for, any of this issue brief’s conclusions. -

Russia's Silence Factory

Russia’s Silence Factory: The Kremlin’s Crackdown on Free Speech and Democracy in the Run-up to the 2021 Parliamentary Elections August 2021 Contact information: International Partnership for Human Rights (IPHR) Rue Belliard 205, 1040 Brussels, Belgium [email protected] Contents I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 II. INTRODUCTION 6 A. AUTHORS 6 B. OBJECTIVES 6 C. SOURCES OF INFORMATION AND METHODOLOGY 6 III. THE KREMLIN’S CRACKDOWN ON FREE SPEECH AND DEMOCRACY 7 A. THE LEGAL TOOLKIT USED BY THE KREMLIN 7 B. 2021 TIMELINE OF THE CRACKDOWN ON FREE SPEECH AND DEMOCRACY 9 C. KEY TARGETS IN THE CRACKDOWN ON FREE SPEECH AND DEMOCRACY 12 i) Alexei Navalny 12 ii) Organisations and Individuals associated with Alexei Navalny 13 iii) Human Rights Lawyers 20 iv) Independent Media 22 v) Opposition politicians and pro-democracy activists 24 IV. HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS TRIGGERED BY THE CRACKDOWN 27 A. FREEDOMS OF ASSOCIATION, OPINION AND EXPRESSION 27 B. FAIR TRIAL RIGHTS 29 C. ARBITRARY DETENTION 30 D. POLITICAL PERSECUTION AS A CRIME AGAINST HUMANITY 31 V. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 37 I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY “An overdose of freedom is lethal to a state.” Vladislav Surkov, former adviser to President Putin and architect of Russia’s “managed democracy”.1 Russia is due to hold Parliamentary elections in September 2021. The ruling United Russia party is polling at 28% and is projected to lose its constitutional majority (the number of seats required to amend the Constitution).2 In a bid to silence its critics and retain control of the legislature, the Kremlin has unleashed an unprecedented crackdown on the pro-democracy movement, independent media, and anti-corruption activists. -

Teach Uyghur Project Educational Outreach Document

TEACH UYGHUR PROJECT EDUCATIONAL OUTREACH DOCUMENT UYGHUR AMERICAN ASSOCIATION / NOVEMBER 2020 Who are the Uyghurs? The Uyghurs are a Turkic, majority Muslim ethnic group indigenous to Central Asia. The Uyghur homeland is known to Uyghurs as East Turkistan, but is officially known and internationally recognized as the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of the People's Republic of China. Due to the occupation of their homeland by the Qing Dynasty of China and the colonization of East Turkistan initiated by the Chinese Communist Party, many Uyghurs have fled abroad. There are several hundred thousand Uyghurs living in the independent Central Asian states of Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan, as well as a large diaspora in Turkey and in Europe. There are and estimated 8,000 to 10,000 Uyghurs in the United States. The Uyghur people are currently being subjected to a campaign of mass incarceration, mass surveillance, forced labor, population control, and genocide, perpetrated by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). About the Uyghur American Association (UAA) Established in 1998, the Uyghur American Association (UAA) is a non-partisan organization with the chief goals of promoting and preserving Uyghur culture, and supporting the right of Uyghur people to use peaceful, democratic means to determine their own political futures. Based in the Washington D.C. Metropolitan Area, the UAA serves as the primary hub for the Uyghur diaspora community in the United States. About the "Teach Uyghur Project" Education is a powerful tool for facilitating change. The goal of this project is to encourage teachers to teach about Uyghurs, and to persuade schools, and eventually state legislatures, to incorporate Uyghurs into primary and secondary school curriculum. -

Zhang Yiming: the Billionaire Tech Visionary Behind Tiktok 20 May 2021, by Helen Roxburgh

Zhang Yiming: The billionaire tech visionary behind TikTok 20 May 2021, by Helen Roxburgh between them as students at one of China's top universities, in the northern city of Tianjin. He then built a name for himself helping other students install computers—which was how he met his university sweetheart, who he later married. In a departing memo unencumbered by the ritual self-congratulation of top executives, Zhang said he is leaving the role because he says he lacks managerial skills and prefers "daydreaming about what might be possible" to running the tech giant. He also hopes to focus on "social responsibility", and is already ranked as one of China's top At just 38 Zhang Yiming has found that having a seat at charitable givers. the top table of China's rambunctious tech scene carries a heavy political and managerial price. But he steps down at a time of great pressure for many Chinese tech companies, with Beijing cracking down on its digital behemouths who wield huge influence over millions of Chinese consumers. Armed with pioneering AI and a sharp nose for youth trends, Zhang Yiming revolutionized internet With a net worth of $36 billion Zhang is now China's video with popular app TikTok and minted himself fifth richest person, according to Forbes. a fortune. Although he is in the upper echelons of the Beijing But at just 38 he has also found that having a seat billionaires' club, Zhang described himself in his at the top table of China's rambunctious tech frank leaving message as "not very social, scene carries a heavy political and managerial preferring solitary activities like being online, price. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Making and Breaking

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Making and Breaking Stereotypes: East Asian International Students’ Experiences with Cross- Cultural/Racial Interactions A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Education by Zachary Stephen Ritter 2013 © Copyright by Zachary Stephen Ritter 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Making and Breaking Stereotypes: East Asian International Students’ Experiences with Cross- Cultural/Racial Interactions by Zachary Stephen Ritter Doctor of Philosophy in Education University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Richard Wagoner, Chair In response to recent budget cuts and declining revenue streams, American colleges and universities are admitting larger numbers of international students. These students add a great deal of cultural and intellectual diversity to college campuses, but they also bring racial stereotypes that can affect cross-racial interaction as well as campus climate. Forty-seven interviews with Chinese, Japanese, and Korean graduate and undergraduate international students were conducted at the University of California, Los Angeles, regarding these students’ racial stereotypes and how contact with diverse others challenged or reinforced these stereotypes over time. Results indicated that a majority of students had racial hierarchies, which affected with whom they roomed, befriended, and dated. American media images and a lack of cross-cultural/racial interaction in home countries led to negative views toward African-Americans and Latinos. Positive cross- racial interactions, diversity courses, and living on-campus did change negative stereotypes; however, a lack of opportunities to interact with racial out-groups, international and domestic student balkanization, and language issues led to stereotype ossification in some cases. This research shows that there is a need for policy and programmatic changes at the college level that promote international and domestic student interaction. -

Experiences of Uyghur Migration to Turkey and the United States: Issues of Religion, Law, Society, Residence, and Citizenship

_full_alt_author_running_head (neem stramien B2 voor dit chapter en dubbelklik nul hierna en zet 2 auteursnamen neer op die plek met and): 0 _full_articletitle_deel (kopregel rechts, vul hierna in): Uyghur Migration to Turkey and the Usa _full_article_language: en indien anders: engelse articletitle: 0 174 Beydulla Chapter 10 Experiences of Uyghur Migration to Turkey and the United States: Issues of Religion, Law, Society, Residence, and Citizenship Mettursun Beydulla 1 Introduction At least one million Uyghurs now live outside their homeland Xinjiang, also known as the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) and East Turkistan. The experience of migration has been a reality for many years for these Dias- pora Uyghurs. They reside in about 50 different countries around the world, but two locales where Uyghurs reside, Turkey and the US, will be the focus of this paper. First, I will describe the migrations to Turkey—when, why and how they were treated. Then I will focus on the US. Following that, I will describe and analyze the differing experiences of the various waves of migrants in light of five topics. The first topic is religion, where I will compare the traditional dichotomy of migration to a Muslim and/or a non-Muslim state, the Dār al- Islām and Dār al-Kufr. The second topic will be the issue of law and the imple- mentation of changing laws during the periods of migration. The third topic is society, specifically the integration of migrants into their new home cultures. The fourth is residence, which encompasses both legal and illegal means of staying or residing in a country and how this impacts the fifth topic, citizen- ship. -

Netizens, Nationalism, and the New Media by Jackson S. Woods BA

Online Foreign Policy Discourse in Contemporary China: Netizens, Nationalism, and the New Media by Jackson S. Woods B.A. in Asian Studies and Political Science, May 2008, University of Michigan M.A. in Political Science, May 2013, The George Washington University A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 31, 2017 Bruce J. Dickson Professor of Political Science and International Affairs The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that Jackson S. Woods has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of September 6, 2016. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. Online Foreign Policy Discourse in Contemporary China: Netizens, Nationalism, and the New Media Jackson S. Woods Dissertation Research Committee: Bruce J. Dickson, Professor of Political Science and International Affairs, Dissertation Director Henry J. Farrell, Associate Professor of Political Science and International Affairs, Committee Member Charles L. Glaser, Professor of Political Science and International Affairs, Committee Member David L. Shambaugh, Professor of Political Science and International Affairs, Committee Member ii © Copyright 2017 by Jackson S. Woods All rights reserved iii Acknowledgments The author wishes to acknowledge the many individuals and organizations that have made this research possible. At George Washington University, I have been very fortunate to receive guidance from a committee of exceptional scholars and mentors. As committee chair, Bruce Dickson steered me through the multi-year process of designing, funding, researching, and writing a dissertation manuscript. -

Northern California Regional Intelligence Center 450 Golden Gate Avenue, 14Th Floor, San Francisco, CA 94102 [email protected], [email protected]

VIA EMAIL Daniel J. Mahoney Deputy Director and Privacy Officer Northern California Regional Intelligence Center 450 Golden Gate Avenue, 14th Floor, San Francisco, CA 94102 [email protected], [email protected] March 17, 2021 RE: California Public Records Act Request Dear Mr. Mahoney, This letter constitutes a request under the California Public Records Act Cal. Gov. Code § 6250 et seq. and is submitted by the Electronic Privacy Information Center. EPIC requests records related to the Northern California Regional Information Center’s (NCRIC) monitoring of protests and use of advanced surveillance technologies. Background The summer of 2020 saw large protests across the country in the wake of the killing of George Floyd. Polls conducted between June 4 and June 22, 2020 estimate that between 15 million and 26 million people attended protests nationwide, marking 2020’s protests as the largest in American history.1 2020 was also a high-water mark for police surveillance of protesters, with reports of aerial and drone surveillance, widespread use of video recording and facial recognition, cellular surveillance, and social media surveillance appearing in news stories across the nation.2 Fusion centers played a prominent role in surveilling protesters, providing advanced tools like facial recognition and social media monitoring to local police.3 The BlueLeaks documents, records 1 Larry Buchanan, Quoctrung Bui, and Jugal K. Patel, Black Lives Matter May Be the Largest Movement in U.S. History, N.Y. Times (July 3, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/07/03/us/george-floyd- protests-crowd-size.html. 2 See e.g., Zolan Kanno-Youngs, U.S. -

Investing in China: Consumers and Technology Recovering

MAY 2020 Investing in China: Consumers and technology recovering FRANKLIN TEMPLETON THINKSTM EQUITY MARKETS Introduction China has been much in the news recently as it handles the COVID-19 virus, and because of political and trade tensions with the West. We continue to believe China remains a growth opportunity for investors. Indeed, by early-March, the Chinese A-share market hit a 12-month high and was one of the world’s best-performing equity markets. Our emerging markets team was on the cusp of publishing fresh thoughts on China in January when Beijing locked down China’s economy to flatten the COVID-19 infection curve. In scenes that were soon replayed across the globe, factories, offices, restaurants and shops all closed. Although China’s economy is opening again, it’s not back to normal. Companies like Foxconn, which assembles iPhones for Apple, aren’t back to full employment due to sagging global demand. Overall, retail activity is improving, but discretionary spending remains muted, while lingering anxieties over infections are accelerating consumer migration to more online purchases and home deliveries. That said, the macro themes and companies our emerging markets analysts wrote of in January remain relevant to investors looking for growth opportuni- ties today. In the near-term, we believe the business prospects for the companies we highlight have brightened. Whether trade tensions eventually prompt companies like Apple to pull supply chains out of China remains to be seen. This updated discussion offers a window into a post-COVID-19 economic recovery. Stephen Dover, CFA Head of Equities Franklin Templeton 2 Investing in China: Consumers and technology recovering Innovation at work In the wake of the global COVID-19 recession, we believe China’s long-term prospects remain intact. -

Russia's 'Dictatorship-Of-The-Law' Approach to Internet Policy Julien Nocetti Institut Français Des Relations Internationales, Paris, France

INTERNET POLICY REVIEW Journal on internet regulation Volume 4 | Issue 4 Russia's 'dictatorship-of-the-law' approach to internet policy Julien Nocetti Institut français des relations internationales, Paris, France Published on 10 Nov 2015 | DOI: 10.14763/2015.4.380 Abstract: As international politics' developments heavily weigh on Russia's domestic politics, the internet is placed on top of the list of "threats" that the government must tackle, through an avalanche of legislations aiming at gradually isolating the Russian internet from the global infrastructure. The growth of the Russian internet market during the last couple of years is likely to remain secondary to the "sovereignisation" of Russia's internet. This article aims at understanding these contradictory trends, in an international context in which internet governance is at a crossroads, and major internet firms come under greater regulatory scrutiny from governments. The Russian 'dictatorship-of-the-law' paradigm is all but over: it is deploying online, with potentially harmful consequences for Russia's attempts to attract foreign investments in the internet sector, and for users' rights online. Keywords: Internet governance, Russia, RuNet Article information Received: 10 Jul 2015 Reviewed: 03 Sep 2015 Published: 10 Nov 2015 Licence: Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Germany Competing interests: The author has declared that no competing interests exist that have influenced the text. URL: http://policyreview.info/articles/analysis/russias-dictatorship-law-approach-internet-policy