Heraldry in Ireland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

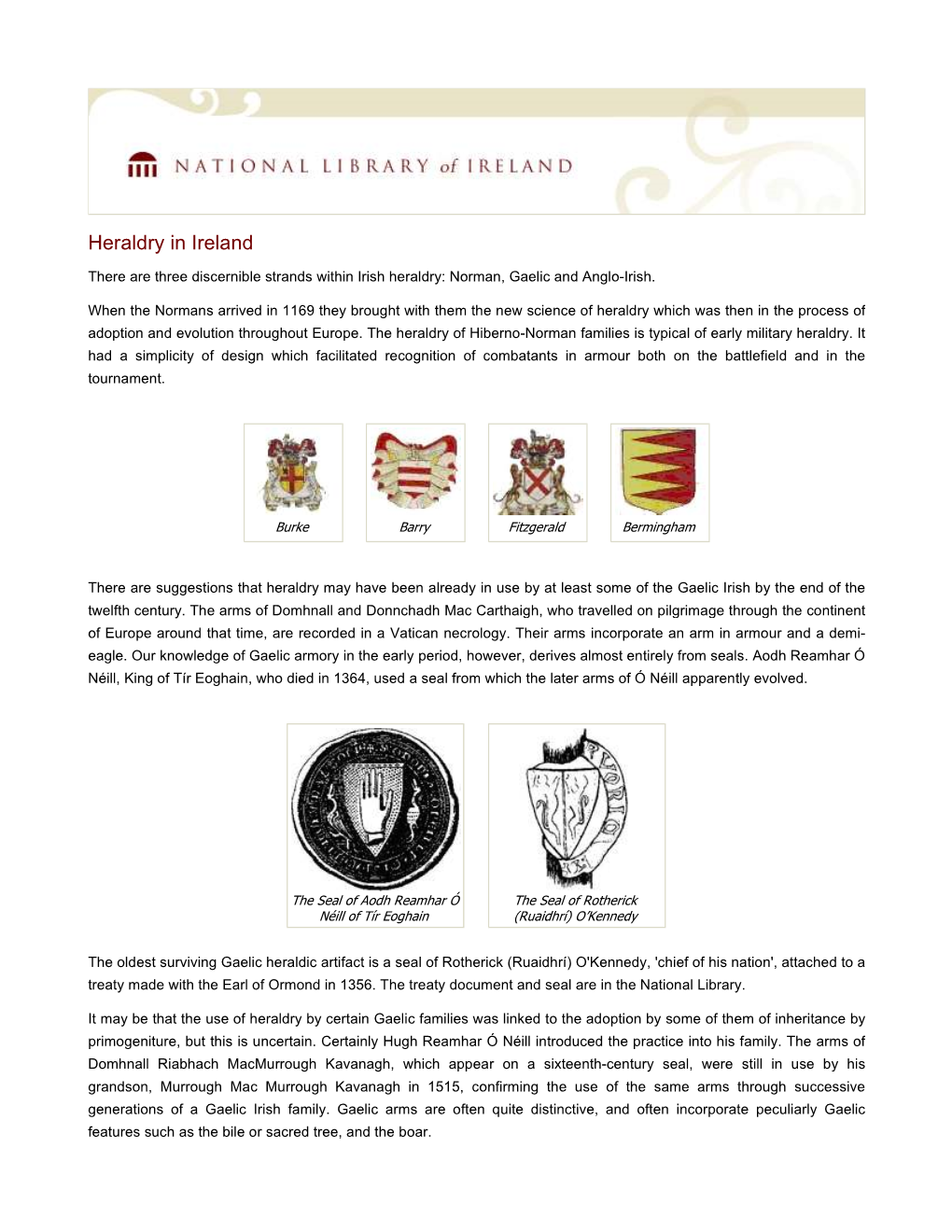

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hour 3: Mo'narchs, Mo' Problems Part I: British Royals 1

Hour 3: Mo'narchs, mo' problems Part I: British royals 1. First monarch to live in Buckingham Palace? Victoria 2. Which English monarch was the youngest of sixteen children? Edward II 3. Who was known to his/her family by the moniker “pussy”? Victoria, Princess Royal (DO NOT ACCEPT “Victoria” or “Queen Victoria”--this is Queen Victoria’s daughter) 4. Name the postcode where Queen Elizabeth II was born. W1J 6QB 5. What does King James II of Scotland have in common with Princess Josephine of Denmark and Prince Wolfgang of Hesse? Twins 6. Patrick Melrose met which member of the British royal family in 1994? Princess Margaret 7. Where did Charles I fail to check out a library book? The Bodleian Library at the University of Oxford 8. Who carved a poem into a wall (or possibly a window) while under house arrest in Oxfordshire? Elizabeth I 9. Which nephew of Henry IV spearheaded Portugal’s colonial activities? Henry the Navigator 10. What did Johannes Klencke give to Charles II in 1660? An atlas 11. Which king’s death was blamed on someone wearing black velvet? William III 12. Which disputed English king’s life was saved by a well-timed bout of diarrhea? King Stephen 13. Which disputed English king was crowned in Ireland? Lambert Simnel 14. Where are three English queens who shared a common cause of death buried? The Church of St Peter ad Vincula, London 15. What drink did the future George IV order after meeting his future wife? Brandy Part II: General Trivia 16. -

Irish History Links

Irish History topics pulled together by Dan Callaghan NC AOH Historian in 2014 Athenry Castle; http://www.irelandseye.com/aarticles/travel/attractions/castles/Galway/athenry.shtm Brehon Laws of Ireland; http://www.libraryireland.com/Brehon-Laws/Contents.php February 1, in ancient Celtic times, it was the beginning of Spring and later became the feast day for St. Bridget; http://www.chalicecentre.net/imbolc.htm May 1, Begins the Celtic celebration of Beltane, May Day; http://wicca.com/celtic/akasha/beltane.htm. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ February 14, 269, St. Valentine, buried in Dublin; http://homepage.eircom.net/~seanjmurphy/irhismys/valentine.htm March 17, 461, St. Patrick dies, many different reports as to the actual date exist; http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11554a.htm Dec. 7, 521, St. Columcille is born, http://prayerfoundation.org/favoritemonks/favorite_monks_columcille_columba.htm January 23, 540 A.D., St. Ciarán, started Clonmacnoise Monastery; http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04065a.htm May 16, 578, Feast Day of St. Brendan; http://parish.saintbrendan.org/church/story.php June 9th, 597, St. Columcille, dies at Iona; http://www.irishcultureandcustoms.com/ASaints/Columcille.html Nov. 23, 615, Irish born St. Columbanus dies, www.newadvent.org/cathen/04137a.htm July 8, 689, St. Killian is put to death; http://allsaintsbrookline.org/celtic_saints/killian.html October 13, 1012, Irish Monk and Bishop St. Colman dies; http://www.stcolman.com/ Nov. 14, 1180, first Irish born Bishop of Dublin, St. Laurence O'Toole, dies, www.newadvent.org/cathen/09091b.htm June 7, 1584, Arch Bishop Dermot O'Hurley is hung by the British for being Catholic; http://www.exclassics.com/foxe/dermot.htm 1600 Sept. -

Guidance on the Use of Royal Arms, Names and Images

GUIDANCE ON THE USE OF ROYAL ARMS, NAMES AND IMAGES 1 The following booklet summarises the legal position governing the use, for commercial purposes, of the Royal Arms, Royal Devices, Emblems and Titles and of photographs, portraits, engravings, effigies and busts of The Queen and Members of the Royal Family. Guidance on advertising in which reference is made to a Member of the Royal Family, and on the use of images of Members of the Royal Family on articles for sale, is also provided. The Lord Chamberlain’s Office will be pleased to provide guidance when it is unclear as to whether the use of “Arms” etc., may give the impression that there is a Royal connection. 2 TRADE MARKS Section 4 (1) of the Trade Marks Act 1994 states: “A trade mark which consists of or contains – (a) the Royal arms, or any of the principal armorial bearings of the Royal arms, or any insignia or device so nearly resembling the Royal arms or any such armorial bearing as to be likely to be mistaken for them or it, (b) a representation of the Royal crown or any of the Royal flags, (c) a representation of Her Majesty or any Member of the Royal Family, or any colourable imitation thereof, or (d) words, letters or devices likely to lead persons to think that the applicant either has or recently has had Royal patronage or authorisation, shall not be registered unless it appears to the registrar that consent has been given by or on behalf of Her Majesty or, as the case may be, the relevant Member of the Royal Family.” The Lord Chamberlain's Office is empowered to grant the consent referred to in Section 4(1) on behalf of Her Majesty The Queen. -

British Royal Banners 1199–Present

British Royal Banners 1199 – Present Geoff Parsons & Michael Faul Abstract The presentation begins with the (accepted) date of 1199, the death of King Richard I, the first king known to have used the three gold lions on red. It continues to show how King Edward III added the French Royal Arms, consequent to his claim to the French throne. There is then the change from “France Ancient” to “France Modern” by King Henry IV in 1405, which set the pattern of the arms and the standard for the next 198 years. The story then proceeds to show how, over the ensuing 234 years, there were no fewer than six versions of the standard until the adoption of the present pattern in 1837. The presentation includes pictures of all the designs, noting that, in the early stages, the arms appeared more often as a surcoat than a flag. There is also some anecdotal information regarding the various patterns. Anne (1702–1714) Proceedings of the 24th International Congress of Vexillology, Washington, D.C., USA 1–5 August 2011 © 2011 North American Vexillological Association (www.nava.org) 799 British Royal Banners 1199 – Present Figure 1 Introduction The presentation begins with the (accepted) date of 1199, the death of King Richard I, the first king known to have used the three gold lions on red. Although we often refer to these flags as Royal Standards, strictly speaking, they are not standard but heraldic banners which are based on the Coats of Arms of the British Monarchs. Figure 2 William I (1066–1087) The first use of the coats of arms would have been exactly that, worn as surcoats by medieval knights. -

Hark the Heraldry Angels Sing

The UK Linguistics Olympiad 2018 Round 2 Problem 1 Hark the Heraldry Angels Sing Heraldry is the study of rank and heraldic arms, and there is a part which looks particularly at the way that coats-of-arms and shields are put together. The language for describing arms is known as blazon and derives many of its terms from French. The aim of blazon is to describe heraldic arms unambiguously and as concisely as possible. On the next page are some blazon descriptions that correspond to the shields (escutcheons) A-L. However, the descriptions and the shields are not in the same order. 1. Quarterly 1 & 4 checky vert and argent 2 & 3 argent three gouttes gules two one 2. Azure a bend sinister argent in dexter chief four roundels sable 3. Per pale azure and gules on a chevron sable four roses argent a chief or 4. Per fess checky or and sable and azure overall a roundel counterchanged a bordure gules 5. Per chevron azure and vert overall a lozenge counterchanged in sinister chief a rose or 6. Quarterly azure and gules overall an escutcheon checky sable and argent 7. Vert on a fess sable three lozenges argent 8. Gules three annulets or one two impaling sable on a fess indented azure a rose argent 9. Argent a bend embattled between two lozenges sable 10. Per bend or and argent in sinister chief a cross crosslet sable 11. Gules a cross argent between four cross crosslets or on a chief sable three roses argent 12. Or three chevrons gules impaling or a cross gules on a bordure sable gouttes or On your answer sheet: (a) Match up the escutcheons A-L with their blazon descriptions. -

Scottish Migration to Ireland

SCOTTISH MIGRATION TO IRELAND (1565 - 16(7) by r '" M.B.E. PERCEVAL~WELL A thesis submitted to the Faculty of er.duet. Studies and Research In partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Degree of Master of Arts. Department of History, McGIII UnIversity, Montreal. August,1961 • eRgFAcE ------..--- ---------------..--------------..------ .. IN..-g.JCTI()tf------------------..--·----------...----------------..-..- CHAPTER ONE Social and Economic Conditions in UI ster and Scotland..--.... 17 CtMPTER TWO Trade and Its Influence on Mlgratlon-------------------..-- 34 CHAPTER ItREE Tbe First Permanent Foothold---------..-------------------- 49 CHAPTER FOUR Scottish Expansion In Ir.land......-------------..-------......- 71 CHAPTER FIVE Rei 1910n and MIgratlon--------------·------------------------ 91 CHAPTEB SIX The Flnel Recognition of the Scottish Position In I reI and....-------·-----------------------------.....----------..... 107 COffCl,US IQN-..--------------------·---------·--·-----------..------- 121 BIBl,1 ~--------------.-- ....-----------------.-----....-------- 126 - 11 - All populatlons present the historian with certain questions. Their orIgins, the date of their arrival, their reason for coming and fInally, how they came - all demand explanatIon. The population of Ulster today, derived mainly from Scotland, far from proving 8n exception, personifies the problem. So greatly does the population of Ulster differ from the rest of Ireland that barbed wire and road blocks period Ically, even now, demark the boundaries between the two. Over three centuries after the Scots arrived, they stili maintain their differences from those who Inhabited Ireland before them. The mein body of these settlers of Scottish descent arrived after 1607. The 'flight of the earls,' when the earls of Tyron. and Tyrconnell fled to the conTinent, left vast areas of land In the hands of the crown. Although schemes for the plantation of U.lster had been mooted before, the dramatic exit of the two earls flnelly aroused the English to action. -

The Eagle's Villa Pizza Restaurant and Carry

`Dinners The Eagle’s Villa Pizza Spaghetti Dinner-Spaghetti with Small Salad and Roll------------------$9.00 Spaghetti Ala. Carte --------------------------------------------------------------------$6.00 Restaurant and Carry Out Baked Spaghetti-Cheese covered and baked-------- Sm. $5.75 Lg. $8.20 Smothered Meatballs- (4) Cheese covered and baked ----------------$4.85 Serving New Albany since 1971 Meatballs $.90--Garlic Bread $1.85-- with Cheese $ 3.50 2 N. High St., New Albany, Ohio Fish Dinner- (2) pieces White Icelandic Cod, 855-7600 or 855-2231 French Fries & Slaw-------------------------------------------------------------------------$8.40 Open Sunday 4:00 PM to 10:00 PM Shrimp Dinner- (21) with French Fries and Slaw--------------------------$8.40 Mon. – Thurs. 10:30 AM to 10:00 PM Chicken Tenders- (4) with French Fries ---------------------------------------$8.40 Fri. & Sat. 10:30 AM to 11:00 PM Side Orders We fry with 100% peanut oil for taste and health Visit us at www.eagles-pizza.com French Fries -------------------------------------------------------------------------------$1.95 Join our fan page on Facebook Cheesy Bacon French Fries -------------------------------------------------------$4.50 Fried Cauliflower -------------------------------------------------------------------------$4.00 Pizza Menu Fried Mushrooms ------------------------------------------------------------------------$4.00 Regular Thin & Crispy *** Jalapeno Poppers ------------------------------------------------------------------------$4.25 Small 11 Inch -

From Charlemagne to Hitler: the Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire and Its Symbolism

From Charlemagne to Hitler: The Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire and its Symbolism Dagmar Paulus (University College London) [email protected] 2 The fabled Imperial Crown of the Holy Roman Empire is a striking visual image of political power whose symbolism influenced political discourse in the German-speaking lands over centuries. Together with other artefacts such as the Holy Lance or the Imperial Orb and Sword, the crown was part of the so-called Imperial Regalia, a collection of sacred objects that connotated royal authority and which were used at the coronations of kings and emperors during the Middle Ages and beyond. But even after the end of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, the crown remained a powerful political symbol. In Germany, it was seen as the very embodiment of the Reichsidee, the concept or notion of the German Empire, which shaped the political landscape of Germany right up to National Socialism. In this paper, I will first present the crown itself as well as the political and religious connotations it carries. I will then move on to demonstrate how its symbolism was appropriated during the Second German Empire from 1871 onwards, and later by the Nazis in the so-called Third Reich, in order to legitimise political authority. I The crown, as part of the Regalia, had a symbolic and representational function that can be difficult for us to imagine today. On the one hand, it stood of course for royal authority. During coronations, the Regalia marked and established the transfer of authority from one ruler to his successor, ensuring continuity amidst the change that took place. -

Imagereal Capture

113 The Law of Arms in New Zealand: A Response Gregor Macaulay* :Noel Cox has written that "Ifany laws of arms were inherited by New Zealand, it 'was the Law of Arms of England, in 1840",1 and that in England and l'Jew Zealand today "the Law of Arms is the same in each jurisdiction",2 The statements cannot both be true; each is individually mistaken; and the English la~N of arms is in any case unworkable in New Zealand. In England, the laws of arms may be defined as the law governing "the use of anms, crests, supporters and other armorial insignia [which] is to be found in the customs and usages of the [English] Court ofChivalry",3 "augmented either by rulings of the [English] kings of arms or by warrants from the Earl Marshal [of England]".4 There are several standard reference books in English heraldry, but not even one revised and edited by a herald may, in his own words, be considered "authoritative in any official sense",5 and a definitive volume detailing the law of arms of England has never been published. A basic difficulty exists, therefore, in knowing precisely what the content of the law is that is being discussed. Even in England there are some extraordinary lacunae. For instance, the English heralds seem not to know who may legally inherit heraldic badges.6 If the English law of arms of 1840 had been inherited by New Zealand it would have come within the ambit of the English Laws Act 1858 (succeeded by the English Laws Act 1908). -

Heraldry Act: Application for Registration of Heraldic

STAATSKOERANT, 15 JULIE 2011 No.34447 7 GOVERNMENT NOTICES GOEWERMENTSKENNISGEWINGS DEPARTMENT OF ARTS AND CULTURE DEPARTEMENT VAN KUNS EN KULTUUR No. 568 15 July 2011 BUREAU OF HERALDRY APPLICATION FOR REGISTRATION OF HERALDIC REPRESENTATIONS AND A NAME AND OBJECTIONS THERETO SECTIONS 7, 7A AND 7B OF THE HERALDRY ACT, 1962 (ACT NO. 18 OF 1962) The undermentioned bodies and persons have applied in terms of section 7 of the Heraldry Act, 1962 (Act No. 18 of 1962), for the registration of their heraldic representations and a name. Anyone wishing to object to the registration of these heraldic representations and a name on the grounds that such registrations will encroach upon rights to which he or she is legally entitled should do so within one month of the date of publication of this notice upon a form obtainable from the State Herald, Private Bag X236, Pretoria, 0001. 1. APPLICANT: Emmanuel Nursing School H4/3/1/4118) BADGE: On a roundle Murray a nurse's lamp Or, between in Chief an open book Argent bot.tnd Sable, and in base an open laurel wreath Argenf. MOTTO: ONS GLO DAAROM KAN ONS 2. APPLICANT: lnkomati Catchment Management AgencyH4/3/1/4111} BADGE: On a ·background Argent, issuant from two wavy bats AZure, dexter a demi sun Tenne. 3. APPLICANT: Lekwa-Teemane Local Municipality• H4/3/2/823} BADGE: In front of a pile inverted embowed Vert, a traditional clay pot abaisse proper, ensigned of a sunburst Or, surmounted of a facetted diamond of Argent and Azure. MOTTO: (above the badge) SHARED BENEFITS FOR ALL 8 No.34447 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 15 JULY 2011 4. -

Government of Ireland Act, 1920. 10 & 11 Geo

?714 Government of Ireland Act, 1920. 10 & 11 GEo. 5. CH. 67.] To be returned to HMSO PC12C1 for Controller's Library Run No. E.1. Bin No. 0-5 01 Box No. Year. RANGEMENT OF SECTIONS. A.D. 1920. IUD - ESTABLISHMENT OF PARLIAMENTS FOR SOUTHERN IRELAND. AND NORTHERN IRELAND AND A COUNCIL OF IRELAND. Section. 1. Establishment of Parliaments of Southern and Northern Ireland. 2. Constitution of Council of Ireland. POWER TO ESTABLISH A PARLIAMENT FOR THE WHOLE OF IRELAND. Power to establish a Parliament for the whole of Ireland. LEGISLATIVE POWERS. 4. ,,.Legislative powers of Irish Parliaments. 5. Prohibition of -laws interfering with religious equality, taking property without compensation, &c. '6. Conflict of laws. 7. Powers of Council of Ireland to make orders respecting private Bill legislation for whole of Ireland. EXECUTIVE AUTHORITY. S. Executive powers. '.9. Reserved matters. 10. Powers of Council of Ireland. PROVISIONS AS TO PARLIAMENTS OF SOUTHERN AND NORTHERN IRELAND. 11. Summoning, &c., of Parliaments. 12. Royal assent to Bills. 13. Constitution of Senates. 14. Constitution of the Parliaments. 15. Application of election laws. a i [CH. 67.1 Government of Ireland Act, 1920, [10 & 11 CEo. A.D. 1920. Section. 16. Money Bills. 17. Disagreement between two Houses of Parliament of Southern Ireland or Parliament of Northern Ireland. LS. Privileges, qualifications, &c. of members of the Parlia- ments. IRISH REPRESENTATION IN THE HOUSE OF COMMONS. ,19. Representation of Ireland in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom. FINANCIAL PROVISIONS. 20. Establishment of Southern and Northern Irish Exchequers. 21. Powers of taxation. 22. -

The Eagle Eye Winter 2015-2016

The Eagle Eye Winter 2015-2016 Bald Eagle Watching Days Set for January 15-16 Preparation for the 29th annual Bald presentations will be made. Frank at the River Arts Center Gallery form Eagle Watching Days (BEWD) is near- LaCour and his grandchildren will tell 8 a.m. to 3 p.m., staffed by representa- ly complete with a new birds of prey the story of Old Abe, the Wisconsin tives from the Bureau of Natural Her- show locked in for three shows on Jan Civil War Eagle. LaCour's family in the itage conservation and Ferry Bluff Ea- 15-16. Eau Claire area bought the young eagle gle Council. The Schlitz Audubon Nature Center from Chippewa Indians and then gave FBEC also will sell raffle tickets at of Milwaukee will bring its inter-active it to the local military unit preparing to the River Arts Center throughout the raptor show to the River Arts Center- go into the Civil War. Cathy Frasier, a day Saturday, with the drawing after for a show at 7 p.m. Friday, Jan. 15, Ferry Bluff Eagle Council member, 3:30 p.m. Prizes include a spotting plus two more shows on Saturday also will share some of her experiences scope and a pair of binoculars donated morning and again in the afternoon. as a chat room moderator for the Dec- as well as some framed pictures. Win- All shows are free and open to the orah eagle cam project. ners need to be present to pick up public. An eagle release by Marge Gibson their prizes at the River Arts Center on Joining the Audubon Nature Cen- of Raptor Education Group Inc.