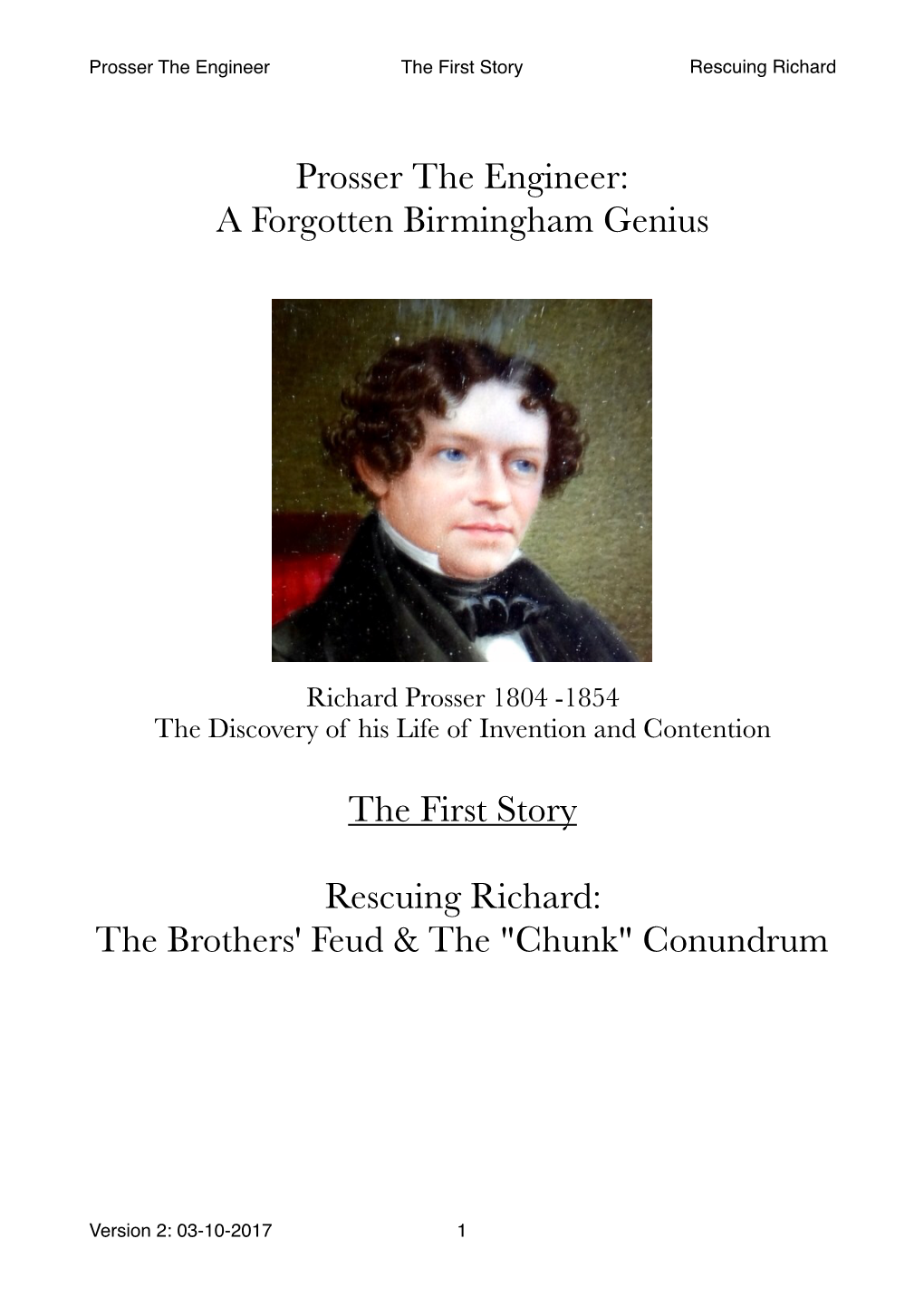

Rescuing Richard (2) 03-10-2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M T/&Djd-Huu4'jkiftmf, ) 'Imuaf Ify ^€E/^Anj

m t/&dJd-HUu4'Jkif tmf , ) 'iMuafify ^€e/^anJ The one Idea which History exhibits as evermore developing itself into greater distinctness is the Idea of Humanity the noble e eavour to 5 u ; throw down all the barriers erected between men by prejudice and one-sided views ; and by setting aside the distinctions or Kengion, Country, and Colour, to treat th,e whole Human race as one broth.erh.ood , having one great object—the free development or our sjpmtual nature."—Humboldt's Cosmos. ^ ©on tentss. NEWS OF THE WEEK— page What is being Done by the Who Gave the " Timid Coun- Henri Heine "" 1017 A mtional Party '. ™^^—== ^^" 103* SS^B^^iSf £S p«bl.c 3S ^S^t ' " " ££ |hl S?;.iir: whiston- -:::::::::::: $2 PuE^n^AVsr::: iffi affairs- fS&SIKKfi^" 1SS1 Disfranchisement of Truehold " Norton Street," Marylebone 1038 The Newspaper Stamp Re- PORTFOLIO— Land Voters 103-i Catholics in Municipalities ... 1038 turns 1042 Underneath .. , 1052 Reinforcements for the East ... 1034 Tho Danish Struggle 103a The Working Man and his _;.,_ -„_ ,. Odd Proceedings 1034 The Sydenham Pete.... 1039 Teachers 1012 THE ARTS- Iiord Palmerston at Itomsey 1035 The Czar's own. Account ©f his Increase of the Army 1043 Drury Lane . 1053 £he Loss of the Arctic : 1035 Mission ; 1039 China Made Useful 1044 Mr. Peto and the Kins of Den- Germany and Bussia 1039 «»-«, miiu/.ii _ mark ••. .-.. 103G Another Arctic Expedition ... 1039 OPtN council- Births, Marriages, and Deaths 105 1 Mr.Bernal Osborne iti Tipperary 1036 ¦ The Public Health 1039 Babel 1014 „„.«.-.«-.. Mr. Urquhar-t at Newcastle 1037 Labour Movement in October 1040 COMMERCIAL AFFAIRS- College 1037 The LITERATURE-l lTCO . -

Mtws Nf Tlje Wnk. Would Puzzle Even Mr

¦ / " i ~^ " The one Idea which History exhibits as evermore developing itself into greater distinctness is the Idea of Humanity the noble endeavour to throw down all the barriers erected betvveen. men by prej udice aad one-sided views ; aud by settm°" aside ttie distinctions of Hehgion, Countrj', and Colour, to treat the whole Human race as one brotherhood, having one great object—the free development of our spiritual nature."—Uumbol&t'' s Cosmos¦. (Stantrnts. NcWS OF THE WEEK— »»oe What is being Done by tho Who Gave the " Timid Coun- w Henri Heine 1047 Central Association for the sels 1040 Tho \n<rel in the House 1048 A National Party 10:54 Aid of Soldiers' Wives and Miscellaneous [..[.. 1040 Habits and Men ival 1049 fc^n " 1043 The War 10-3-A Widows ..;. 1037 r->i, O i ,„ « ,-,- ., me £rvn^andIrvine and Suiritu-vlME Riu'iv-Vlcv . 1O4Q J3 Tho»!v, Mr. Whi8ton 1034 Public Opinion in America ... 1037 PUBLIC AFFAIRS- ¦Testimonial to the Rev. R. Canada , 103S Louis Napoleon and the United Three Novels 1051 Whistou 1034 Our Civilisation 1038 States 1041 Disfranchisement of Freehold " Norton Street," Marylebone 1038 The Newspaper Stamp Kc- PORTFOLIO— Land Voters 1034 Catholics in Municipalities ... 1038 turns 1042 Underneath... 1052 Reinforcements for the East ... 10;5i The Danish Struggle , 1039 The "Working Man and his _,_._ Odd Proceedings 3034 The Sydeiiham Pete.... 1039 Teachers 1042 THE A RTS— lord Palmerston at Roinsey U0S5 The Czar's own Account of his Increase-of the Army 1043 Drury Lane . 1053 The Loss of the Arctic. -

Constructing Corporate Identity Through Portraiture

Constructing corporate identity before the corporation: fashioning the face of the first English joint stock banking companies through portraiture Article Accepted Version Newton, L. and Barnes, V. (2017) Constructing corporate identity before the corporation: fashioning the face of the first English joint stock banking companies through portraiture. Enterprise and Society, 18 (3). pp. 678-720. ISSN 1467-2235 doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/eso.2016.90 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/70075/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/eso.2016.90 Publisher: Oxford University Press All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online Constructing Corporate Identity before the Corporation: Fashioning the Face of the First English Joint Stock Banking Companies through Portraiture Victoria Barnes (Max Planck Institute for European Legal History) and Lucy Newton (Henley Business School, University of Reading)1 This article considers how the joint-stock banks established trust within the local marketplace. We undertake a new investigation of pictures of senior bank management. Building on the expansion of the art market in the nineteenth century, joint-stock banks used portraits as a public and visual mechanism to commemorate their successes and accomplishments. -

Edition 211 Autumn

Boundary Edition 211 Post Autumn The 24th Bonfire Rally this year led by Dave Dent comes to an end. How many Society’s would see over 25 members turn up around 8 o’clock the morning after to clear up? Answer-The BCN Society!!! Thank you to all of them. The Journal of the Birmingham Canal Navigations Society Free to members £1 when sold Boundary Post Winter 2016 Boundary Post Winter 2016 Council Members - 2014 - 2015 President : Martin O’Keeffe Vice-Presidents: Ron Cousens, Phil Clayton, Cllr. David Sparks, Rob Starkey, Chairman & web man: Press & Publicity: CHARLEY JOHNSTON 07825816623 Kath O’’Keeffe [email protected] [email protected] Vice Chair & Rally Organiser Press & Publicity Assistant BARRIE JOHNSON 0121 422 4373 Martin O’Keeffe [email protected] [email protected] Treasurer: Sales: DAVE DENT REBECCA SMITH KEARY 38 Greenland Mews, London, SE8 5JW [email protected] 01562 850234 020 8691 9190 [email protected] Health & Safety Secretary: & Planning Officer VACANT POSITION IVOR CAPLAN tel: 07778685764 [email protected] Supporting members to Council Membership Talks and Presentations ALAN VENESS tel: 0121 355 4732 PHIL CLAYTON 07890921413 43 Pilkington Ave, Sutton Coldfield, B72 [email protected] 1LA email: [email protected] Work Party Administrator Work Party Co-ordinator: Michael Smith-Keary 01562 850234 MIKE ROLFE 07763 171735 [email protected] [email protected] BCNS Explorer Cruise Buildings & Heritage Stuart & Marie Sherratt 07510167288 VACANT POSITION [email protected] -

The Peterhead Almanac (And Buchan)

PETERHEAD S. 4L'f5 ALMANAC AND DIRECTORY ^835. PETERHEAD, 1853 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/peterheadalmanac1853dire y x\j\ m-: w\ \T I) - DIRRCTORY. & STATIOIJER, EESPECTFULLY Solicits attention to his present | Stock of Books and Stationery which is carefully se- '^^1 lected ; consisting of a large Assortment of Books in History, Science, Novels, and General Literature ; all the School Books in general use '; Papers—including Writing, Drawing, Cart- tridge and Fancy Papers ; Envelopes, all sizes and qualities ; Merchants' Account Books, Day Books, Ledgers, Letter Books, Memorandum Books for 1853, ^d. to Is. Aceoimt Books Milled and Bomid to any Pattern- W. L. T. has just got to hand a good supply of Diaries for 185S. Almanacks pok 1853. Letts' Diaries, 4s 6d, 4s, 3s, Oliver and Boyd's*, 4s, and 3d 2s 6d. Is, and 6d Aberdeen Almanack, 23 6d T. J. and J. Smith's do., Is 6d Uncle Tom's Almanack, Is Is, and 6d Illustrated Exhibitor, do. 6d Lurasden ^ Sons' do, 3s and 2s Dietrichsen and Hannay's Al- Renshaw's do. Is manack, 6d Oliver and Boyd's, do. 2s Glenny's Garden Almanack, Tide Tables for 1853, Is 6d, Is Is Nautical Almanacks, 1853-54 Punch's Almanack, 3d All the London and Edinhurgh Periodicals, Netv Boohs, and M'lisic, supplied as published. In great variety of Binding. ?i9 :3n ^tmivt.iwi t\ Mx\$\i UocRs, aitb '3mUin'$ C^w^ Mmt, '-JHt^ William L. Taylor's list, Continued. mw liijii. The Wide, Wide World, by Elizabeth Withevel). -

A History of Tooting Common the Common Story a History of Tooting Common

The Common Story A History of Tooting Common The Common Story A History of Tooting Common Edited by Katy Layton-Jones Acknowledgements This book has only been made possible due to the many hours contributed by volunteers from the Tooting area over a period of more than four years. A large proportion of the historical research that underpins this book was carried out by these volunteers and special thanks are due to the Tooting History Group for also engaging the local community in the historical research project through guided walks, talks and special events. Particular thanks are extended to Janet Smith for her commitment to the project throughout. Thanks are also extended to: Jim Ballinger Victoria Carroll Pamela Greenwood Deborah Ballinger-Mills Grace Etherington Tessa Holubowicz Anna Blair Paul Gander Susanna Kryuchenkova Philip Bradley Graham Gower Kevin Pinto John Brown Clare Graham Cynthia Pullin List of abbreviations BDANHS Balham & District Antiquarian & Natural History Society HLF Heritage Lottery Fund LA Lambeth Archives LBSCR London, Brighton, and South Coast Railway Company LCC London County Council LMA London Metropolitan Archive MA Morning Advertiser MBW Metropolitan Board of Works MERL Museum of English Rural Life MPGA Metropolitan Public Gardens Association MOLA Museum of London Archaeology PCOSC Parks, Commons, and Open Spaces Committee of the Metropolitan Board of Works POSC Parks and Open Spaces Committee of London County Council SN The Streatham News and Tooting, Balham, Tulse Hill Advertiser TNA The National Archives WBC Wandsworth Borough Council (formerly Wandsworth Metropolitan Borough Council, WMBC) WBN Wandsworth Borough News WECPR West End and Crystal Palace Railway Company WHS Wandsworth Heritage Service Preface ‘The Common Story’ is part of the Tooting Common Heritage Project, supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund. -

A Comparative Study of the 1852-1857 and the 1895-1900 Parliaments

Businessmen in the House of Commons: A Comparative Study of the 1852-1857 and the 1895-1900 Parliaments BY C2009 Alexander S. Rosser Submitted to the graduate degree program in History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ___________________________________________ Victor Bailey, Chairman ___________________________________________ Theodore A. Wilson ___________________________________________ Joshua L. Rosenbloom ___________________________________________ J. C. D. Clark ___________________________________________ Thomas J. Lewin Date Defended 11 May, 2009 The Dissertation Committee for Alexander S. Rosser certifies That this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Businessmen in the House of Commons: A Comparative Study of the 1852-1857 and the 1895-1900 Parliaments Committee: ___________________________________________ Victor Bailey, Chairman ___________________________________________ Theodore A. Wilson ___________________________________________ Joshua L. Rosenbloom ___________________________________________ J. C. D. Clark ___________________________________________ Thomas J. Lewin Date Approved 11 May, 2009 2 Table of Contents Page Table of Contents 3 Acknowledgements 4 List of Tables 5 List of Abbreviations 12 Introduction 16 Chapter One Businessmen in the House of 26 Commons,1852-1857 Chapter Two Businessmen in the House of 110 Commons 1895-1900 Chapter Three Comparison and contrasts 241 between the Parliament of 1852-1857 and the Parliament of 1895-1900 Chapter Four The Wiener Thesis of 271 Late20th Century British Business Failure Endnotes 350 Bibliography 363 3 Acknowledgements This project first started many years ago as a master’s thesis under the direction of the late Professor John Stack of the University of Missouri at Kansas City. Professor Victor Bailey of the University of Kansas very graciously supported my efforts to extend the work to include a later Parliament and a detailed look at the Wiener Thesis. -

The History of South Staffordshire Waterworks

THE HISTORY OF SOUTH STAFFORDSHIRE WATERWORKS COMPANY 1853 - 1989 Johann Van Leerzem Brian Williams CONTENTS Chapter 1 1853 - 1864 Page The South Staffordshire Mining District Water Company 1 Merger plans fail 3 Founding of the South Staffordshire Water Works Company 4 The 1853 Act of Parliament 6 Early meetings and publicity 9 Tenders for the works 12 Proposed alteration to plans and Lichfield's opposition 13 Digging the first sod 16 Opposition to the 1857 Amendment Act 18 Letting of contracts 22 Walsall Reservoir 23 Opening of the works 24 A supply to Walsall 28 Dudley's water supply 31 The 14th half yearly meeting report 36 Improving the mains network and the Take-Over of Dudley Water Works Company 37 Coneygre Reservoir, Tipton 39 First engineering staff appointment 40 West Bromwich water supply 40 Problems in the early eighteen sixties 41 Summary of the works 43 The 1864 Act of Parliament 44 Resignation of John McClean as Engineer and appointment of William Vawdry 45 Chapter 2 1865 - 1894 Third Engine installed at Lichfield 46 The 1866 Act of Parliament 46 Take over of Burton on Trent Water Works Company 47 Tamworth's water supply 48 Sale of early plant 52 Death of S.H. Blackwell 52 Increase on revenue account 53 Death of first Chairman 53 Election of second Chairman 53 Shavers End Reservoir at Dudley 54 The West Bromwich, Oldbury and Smethwick Water Bill 57 Supply difficulties in the 1870's 61 New pumping station at Wednesbury 63 Additional plant at Lichfield 64 Walsall's supply problems 65 Temporary water supplies obtained 66 Death of a Chairman and the beginning of the Frank James era 67 Dr. -

Midland Bank Historical Collection

«£? MIDLAND BANK HISTORICAL COLLECTION 81U MID pam CATALOGUE of the EXHIBITION OF DOCUMENTS AND OTHER ITEMS illustrating the HISTORY OF THE MIDLAND BANK MIDLAND BANK POULTRY LONDON, E.C. 2 INTRODUCTION The first joint stock banks in England were established little more than a century-and-a- quarter ago. Until then commercial banking had Private been conducted by small partnerships, and firms banks of this kind increased rapidly in number to serve the expanding activity in trade and commerce which followed the industrial revolution. By the first decade of the nineteenth century over seven hundred country banks were in existence, many having developed as a side line to trading or Note manufacturing activities, and nearly all of them issues issued their own notes. Some of these early private banks were wisely managed and had sufficient resources, but others were far from secure and in times of crisis large numbers of them failed. Reform of banking constitutions began in 1826, Joint when new legislation first permitted joint stock stock banks to be established in the country, and it was banks carried a stage further in 1833, when it was recognized that joint stock banks could be formed in London provided that they did not issue notes. In 1844 the Bank Charter Act set in train a process of consolidating note issues into the hands of the central bank, and in the same year a banking code was introduced which required Bank all new joint stock banks to obtain a charter. charters This requirement was withdrawn in 1857 and in the following year banks were permitted to adopt limited liability in respect of all liabilities except note issues, though twenty years and more were to pass before this form of shareholding was generally accepted. -

Russell's Morayshire Register, and Elgin and Forres Directory

APSJ.2og.03s ,\/ Digitized by the Internet' Archive in 2010 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/russellsmorayshi1852elgi :! RUSSELL'S MORAYSHIRE REGISTER, AND ELGIN AND FORRES DIRECTORY, FOE 1852, Mtins Heap fear, DEDICATED, BY SPECIAL PERMISSION, TO :&e mm Hon- Cfte ©arl of ffitt. ELGIN:; PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY ALEX. RUSSELL, CO U RANT OFFICE, AND SOLD BY ALL BOOKSELLERS. Price Is. Qd. Bound in Cloth, • . — INDEX TO THE CONTENTS. PART I.—GENERAL ALMANACK. Arehbishops of England 54 Palaces, Hereditary Keepers. ..71 Assessed Taxes 43 Parliaments, Imperial 68 Bank Holidays., 7 Peers, House of.., 53 Banks and Banking Companies 45 Peerage, Scottish ,70 Banks & Branches in Scotland 45 Peers, Scottish Representative57 Bill Card for 1852....... 50 Peers, Irish Representative 57 Bishops of England 55 Peers, Officers of the House.. ..58 British Empire, Extent and Peeresses in their own Right... 58 Population of 52 Prelates, Irish Representative.. 58 British Ministry 53 Quarters of the Year, 8 Cattle, Rule for Weighing 41 Railway Communication 73 Chronicle and Obituary, Royal Family 52 1850-51. 77 Salaries and Expenses, Table Chronological Cycles .8 for Calculating 36 Commons, House of, .....58 Savings' Bank, National Se- Commons, Officers of the curity.., 44 House of 68 Scotland, Extent, &c 44 Corn, Duties on , 40 Scotland, Judges and Officers.. 69 Distance Table of Places in Scotland, Officers of State in... 71 Elginshire 7 Scotland, Population, Lords- Eclipses of the Sun and Moon 8 Lieutenant, and Sheriffs 69 European States, Population, Scotland, Summary of the Po- and Reigning Sovereigns 52 pulation in 1821, 1831, Excise Duties ...41 1841, and 1851 70 Fairs in Scotland 21 Scotland, Universities of 71 Fairs in North of England 35 Scotland, View of the Pro- Fast Days.... -

GIPE-010590-Contents.Pdf

Dhananjayarao Gadgil Library 111111111111111111111111111111111111111 GIPE-PUNE-O I 0590 A ~{JNDRED' YEARS' OF JOINT .' STOCJ{. 'RANKING CHARLES GE:\CH fa.. HUNDRED YEARS OF JOINT STOCK ~f\.NKI~G . by W.F. Crick and J .. E. Wadsworth . with a Foreword by The Rjght· Honourable Reginald McKenna HODDER & STOUGHTON. PUBLISHERS At ST. PAUL'S 'HOUSE LO~DON, E.C.4 First, printed ~936 . • XM'~)b2...; 3.N6 ~~ IOS~O FOREWORD . ~ , OR those of 'us born in fhe.nrld-Victorian era the history "F related in tJrls bookserv.es ~ a 'I'emarkable record of the . profound changes br~ught·about in our lifetime. It extends' . over a full century-i century of pronounced'gi-owth.and develop ment in every branch qf-economic.life. Whiletlie population of England and Wales has~ost Q.oubled, tJ1e ptocess of consoli dation in .comm~r.ce .$.d indus~ry. has ·~eQ. t9 ·an even more remarkable, expansforl of individual:busiriess units. I The .old family undertaking.and the sm911-scale commerqial and industrial firm have been replaced in great ,meas!lre J;y. the company' organization, and companies have in their .t1l;r.I1 been fused intd large combinations which have developed intO' corporate entities of vast capital resources and scope of operations. The process. has found expression'throughout the whole field of our .busi~ess life. Wh~n we compare ol,lI' past and present organization, the contrast in the size and range of our industrial and commercial units is, next to the general improvement in the standard of living,' the most important econopUc feat~re of the last seventy years. -

Dickensian New Layout

The Letters of Charles Dickens: Supplement XVIII References (at the top of each entry) to the earlier volumes of the British Academy-Pilgrim edition of The Letters of Charles Dickens are by volume, page and line, every printed line below the running head being counted. The Editors gratefully acknowledge the help of the following individuals and institutions: Michael Allen; Guy Baxter (University of Reading, Special Collections); Harry Bennett; Philip Best (Fraser’s Autographs); Amanda Blanchflower; Ray Dubberke; Rose Geach; Jenny Hartley; Roger Hull (Liverpool Record Office); Peter Marchant; Michael Rogers; Dave Sherman (University of Rhode Island, Special Collections). As announced in Supplement XV, minor Corrigenda are now available on the Dickens Fellowship Website. Significant Corrigenda and Internal Corrigenda to the Supplements themselves still appear in the Supplements. Editorial Board: Margaret Brown, Angus Easson (Editors); Malcolm Andrews; Joan Dicks; Leon Litvack; Michael Slater (Consultant Editor). ANGUS EASSON LEON LITVACK MARGARET BROWN JOAN DICKS I, 15.1. To THOMAS BEARD, 2 FEBRUARY [1833] Note 2, col. 2, line 17 after ii, 35). insert The stepson was George Lamert (Lamerte), always referred to by CD and Forster as James: see Michael Allen, CD and the Blacking Factory (St Leonards, 2011), ch. 1 and p. 9. I, 43.22. To THOMAS MITTON, [?20 NOVEMBER 1834] Note 5, col. 2, line 11 for on 20 Feb 24 and imprisonment in the Marshalsea read and imprisonment (he was committed to the Marshalsea Debtors’ Prison, 20 Feb: MS PRO Prisons: Commitment Book), After 28 May 24 delete rest of sentence and substitute , having gone through the Insolvency Court: a legacy from his mother went towards payments to his creditors.