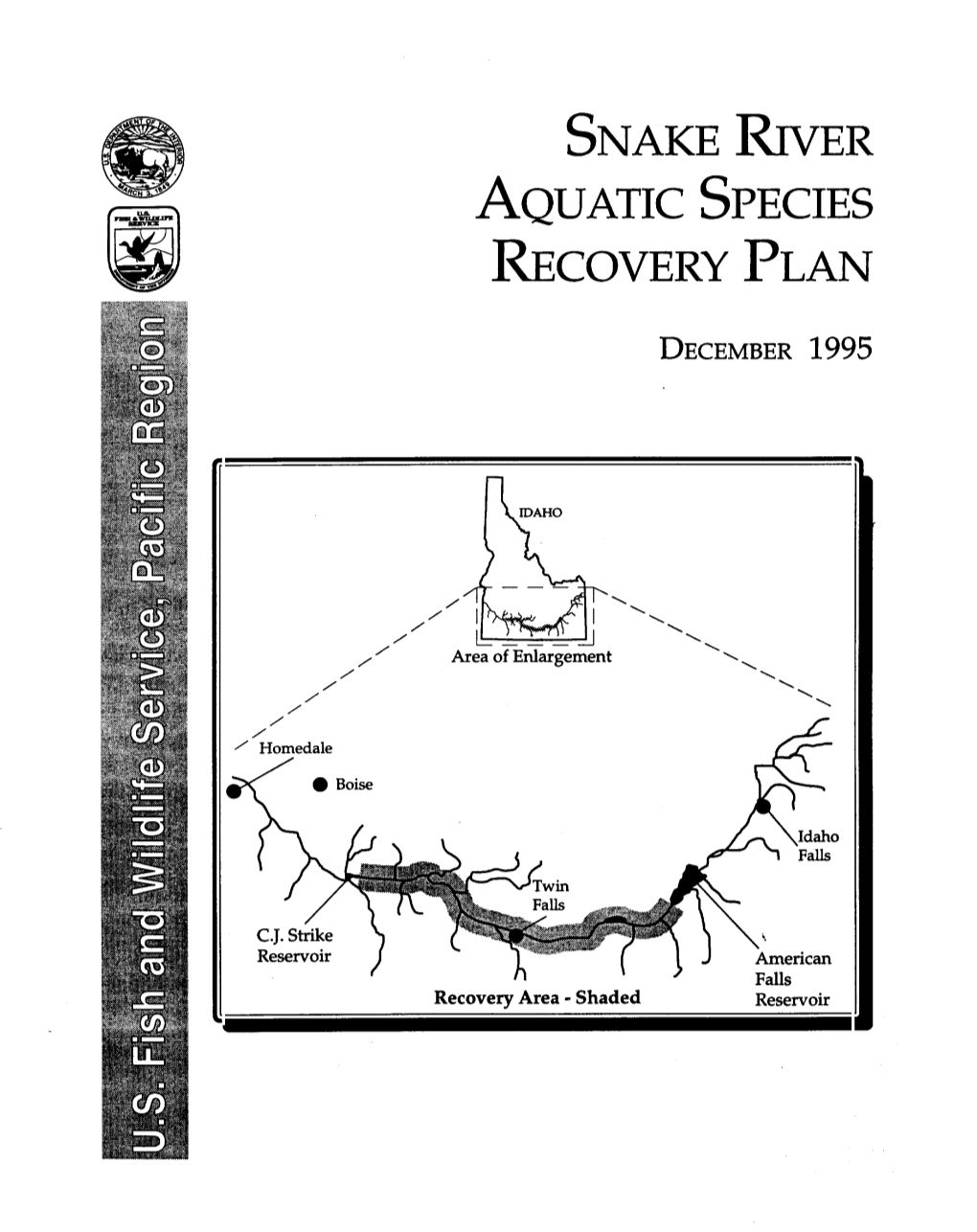

Snake River Aquatic Species Recovery Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geomorphic Assessment Report Big Wood River Blaine County, Idaho

GEOMORPHIC ASSESSMENT REPORT BIG WOOD RIVER BLAINE COUNTY, IDAHO Prepared For Trout Unlimited 300 North Main Street, Hailey, Idah, 83333 Prepared By P. O. Box 8578, 140 E. Broadway, Suite 23, Jackson, Wyoming 83002 October 30, 2015 CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction ................................................................................................................1 2.0 Project Area and Approach ........................................................................................1 3.0 Phase 1: Watershed Assessment ...............................................................................1 3.1 Study Area Sub-Catchments ..........................................................................2 3.2 Geology ..........................................................................................................2 3.2 Roads..............................................................................................................2 3.3 Land Slope .....................................................................................................3 3.4 Soils................................................................................................................3 3.5 Land Cover .....................................................................................................3 3.6 Tributary Catchment Analysis .......................................................................5 3.7 Fire .................................................................................................................5 3.8 Anthropogenic -

Mckern Presentation

WHO KILLED THE SNAKE RIVER SALMON JuneCELILO 1 FALLS COMMERCIAL HARVEST – 1860s to 1970s PEAK HARVEST 43 MILLION POUNDS – 1886 -SPRING CHINOOK SECOND PEAK 1910 – 43 MILLION POUNDS - ALL SPECIES EAST BOAT BASIN - ASTORIA MARINE MAMMAL PROTECTION ACT - 1972 NOAA RECENT ESTIMATE 20 TO 40 % OF SPRING CHINOOK Gold Dredge at Sumpter, Oregon Dredged Powder River Valley Oregon LOGGING WATERSHED DAMAGE EROSION SPLASH DAMS WATER RETENTION ROAD CONSTRUCTION METHODS Mainstem Snake River Dams WITHOUT FISH PASSAGE Oxbow dam – 1961 Shoshone Falls Hells Canyon Dam – (Upper Limit) 1967 Upper Salmon Falls – 1937 WITH FISH PASSAGE Lower Salmon Falls - Lower Granite Dam – 1910 1975 Bliss Dam – 1950 Little Goose Dam 1970 C. J. Strike Dam - Lower Monumental Dam 1952 – 1969 Swan Falls Dam -1901 Ice Harbor Dam - 1962 Brownlee Dam – 1959 SHOSHONE FALLS Tributary Dams Owyhee River Powder River Wild Horse Dam – 1937 Thief Valley Dam – 1931 Owyhee Dam – 1932 Mason Dam - 1968 Boise River Salmon River Anderson Ranch Dam – 1950 Sunbeam Dam – 1909 – 1934 Arrowrock Dam – 1915 Wallowa River Boise R Diversion Dam – 1912 OFC Dam 1898 - 1914 Lucky Peak Dam - 1955 Clearwater River Barber Dam - 1906 Lewiston Dam – 1917 - 1973 Payette River Grangeville Dam – 1910 – 1963 Black Canyon Dam – 1924 Dworshak Dam - 1972 Deadwood Dam - 1929 Malheur River Warm Springs Dam – 1930 Agency Valley Dam – 1936 Bully Creek Dam – 1963 Sunbeam Dam – Salmon River 1909 to 1934 1909 to 1920s - no fish passage 1920s to 1934 - poor fish passage Channel around by IDF&G 1934 NOTE 3 PEOPLE IN RED CIRCLE -

A Review of Fish Passage in Idaho Power Company's

A Review of Fish Passage Provisions in the License Application for the Hells Canyon Complex August 2003 Prepared For Idaho Rivers United And American Rivers By Ken Witty S.P. Cramer and Associates S.P. Cramer & Associates, Inc. 600 NW Fariss Road Gresham, OR 97030 www.spcramer.com S.P. Cramer & Associates, Inc. Hells Canyon Complex August 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................................. iii LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................................... iv LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................................... iv INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 1 HISTORIC PROSPECTIVE ................................................................................................................. 1 PASSAGE AT THE HCC ................................................................................................................ 1 PROPOSED DOWNSTREAM DAMS ............................................................................................ 1 LOWER SNAKE RIVER DAMS .................................................................................................... 2 LOWER SNAKE RIVER COMPENSATION PLAN .................................................................... -

Interior Columbia Basin Mollusk Species of Special Concern

Deixis l-4 consultants INTERIOR COLUMl3lA BASIN MOLLUSK SPECIES OF SPECIAL CONCERN cryptomasfix magnidenfata (Pilsbly, 1940), x7.5 FINAL REPORT Contract #43-OEOO-4-9112 Prepared for: INTERIOR COLUMBIA BASIN ECOSYSTEM MANAGEMENT PROJECT 112 East Poplar Street Walla Walla, WA 99362 TERRENCE J. FREST EDWARD J. JOHANNES January 15, 1995 2517 NE 65th Street Seattle, WA 98115-7125 ‘(206) 527-6764 INTERIOR COLUMBIA BASIN MOLLUSK SPECIES OF SPECIAL CONCERN Terrence J. Frest & Edward J. Johannes Deixis Consultants 2517 NE 65th Street Seattle, WA 98115-7125 (206) 527-6764 January 15,1995 i Each shell, each crawling insect holds a rank important in the plan of Him who framed This scale of beings; holds a rank, which lost Would break the chain and leave behind a gap Which Nature’s self wcuid rue. -Stiiiingfieet, quoted in Tryon (1882) The fast word in ignorance is the man who says of an animal or plant: “what good is it?” If the land mechanism as a whole is good, then every part is good, whether we understand it or not. if the biota in the course of eons has built something we like but do not understand, then who but a fool would discard seemingly useless parts? To keep every cog and wheel is the first rule of intelligent tinkering. -Aido Leopold Put the information you have uncovered to beneficial use. -Anonymous: fortune cookie from China Garden restaurant, Seattle, WA in this “business first” society that we have developed (and that we maintain), the promulgators and pragmatic apologists who favor a “single crop” approach, to enable a continuous “harvest” from the natural system that we have decimated in the name of profits, jobs, etc., are fairfy easy to find. -

Sensitivity of Freshwater Snails to Aquatic Contaminants: Survival and Growth of Endangered Snail Species and Surrogates in 28-D

Sensitivity of freshwater snails to aquatic contaminants: Survival and growth of endangered snail species and surrogates in 28-day exposures to copper, ammonia and pentachlorophenol John M. Besser, Douglas L. Hardesty, I. Eugene Greer, and Christopher G. Ingersoll U.S. Geological Survey, Columbia Environmental Research Center, Columbia, Missouri Administrative Report (CERC-8335-FY07-20-10) submitted to U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) Project Number: 05-TOX-04, Basis 8335C2F, Task 3. Project Officer: Dr. David R. Mount USEPA/ORD/NHEERL Mid-Continent Ecology Division 6201 Congdon Blvd, Duluth, MN 55804 USA April 13, 2009 Abstract – Water quality degradation may be an important factor affecting declining populations of freshwater snails, many of which are listed as endangered or threatened under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. Toxicity data for snails used to develop U.S. national recommended water quality criteria include mainly results of acute tests with pulmonate (air-breathing) snails, rather than the non-pulmonate snail taxa that are more frequently endangered. Pulmonate pond snails (Lymnaea stagnalis) were obtained from established laboratory cultures and four taxa of non-pulmonate taxa from field collections. Field-collected snails included two endangered species from the Snake River valley of Idaho -- Idaho springsnail (Pyrgulopsis idahoensis; which has since been de-listed) and Bliss Rapids snail (Taylorconcha serpenticola) -- and two non-listed taxa, a pebblesnail (Fluminicola sp.) collected from the Snake River and Ozark springsnail (Fontigens aldrichi) from southern Missouri. Cultures were maintained using simple static-renewal systems, with adults removed periodically from aquaria to allow isolation of neonates for long-term toxicity testing. -

Updated Site Characterization Data Inventory

INL/MIS-16-38127-D DE-EE0007159 Rev. 1 Updated Site Characterization Data Inventory May 2016 DISCLAIMER This information was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the U.S. Government. Neither the U.S. Government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, expressed or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness, of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. References herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trade mark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the U.S. Government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the U.S. Government or any agency thereof. INL/MIS-16-38127-D Rev. 1 Updated Site Characterization Data Inventory May 2016 Snake River Geothermal Consortium Hosted by Idaho National Laboratory Idaho Falls, Idaho www.snakerivergeothermal.org Prepared for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Under DOE Idaho Operations Office Contract DE-AC07-05ID14517 CONTENTS ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................................... ix 1. DATA MADE AVAILABLE THROUGH THE GEOTHERMAL DATA REPOSITORY ARCHIVE ......................................................................................................................................... -

Draft Environmental Assessment for the Little Wood River Irrigation District Pressurized Pipeline Irrigation Delivery System

Draft Environmental Assessment for the Little Wood River Irrigation District Pressurized Pipeline Irrigation Delivery System U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Pacific Northwest Region Snake River Area March 2010 The mission of the Department of the Interior is to protect and provide access to our Nation’s natural and cultural heritage and honor our trust responsibilities to tribes. The mission of the Bureau of Reclamation is to manage, develop, and protect water and related resources in an environmentally and economically sound manner in the interest of the American public. Draft Environmental Assessment for the Little Wood River Irrigation District Pressurized Pipeline Irrigation Delivery System U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation Pacific Northwest Region Snake River Area March 2010 Draft Environmental Assessment Little Wood River Irrigation District Pressurized Pipeline Project Acronyms and Abbreviations BLM U.S. Bureau of Land Management BPC Bonneville Pacific Corporation cfs cubic feet per second DEQ Idaho Department of Environmental Quality DPS Distinct Population Segment EA environmental assessment EIS environmental impact statement EPA U.S. Environmental Protection Agency FONSI Finding of No Significant Impact IDFG Idaho Department of Fish and Game IDWR Idaho Department of Water Resources kWh kilowatt-hours LWRID Little Wood River Irrigation District NEPA National Environmental Policy Act NHPA National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 NRCS Natural Resources Conservation Service NRHP National Register of Historic Places PEM palustrine emergent PSS palustrine scrub-shrub Reclamation U.S. Bureau of Reclamation RPW Relatively Permanent Water SCI Soil Condition Index SHPO State Historic Preservation Office SISL Surface Irrigation Soil Loss Model TMDL Total Daily Maximum Load TNW Traditional Navigable Water USDA U.S. -

Geologic Map of the Twin Falls 30 X 60 Minute Quadrangle, Idaho

Geologic Map of the Twin Falls 30 x 60 Minute Quadrangle, Idaho Compiled and Mapped by Kurt L. Othberg, John D. Kauffman, Virginia S. Gillerman, and Dean L. Garwood 2012 Idaho Geological Survey Third Floor, Morrill Hall University of Idaho Geologic Map 49 Moscow, Idaho 83843-3014 2012 Geologic Map of the Twin Falls 30 x 60 Minute Quadrangle, Idaho Compiled and Mapped by Kurt L. Othberg, John D. Kauffman, Virginia S. Gillerman, and Dean L. Garwood INTRODUCTION 43˚ 115˚ The geology in the 1:100,000-scale Twin Falls 30 x 23 13 18 7 8 25 60 minute quadrangle is based on field work conduct- ed by the authors from 2002 through 2005, previous 24 17 14 16 19 20 26 1:24,000-scale maps published by the Idaho Geological Survey, mapping by other researchers, and compilation 11 10 from previous work. Mapping sources are identified 9 15 12 6 in Figures 1 and 2. The geologic mapping was funded in part by the STATEMAP and EDMAP components 5 1 2 22 21 of the U.S. Geological Survey’s National Cooperative 4 3 42˚ 30' Geologic Mapping Program (Figure 1). We recognize 114˚ that small map units in the Snake River Canyon are dif- 1. Bonnichsen and Godchaux, 1995a 15. Kauffman and Othberg, 2005a ficult to identify at this map scale and we direct readers 2. Bonnichsen and Godchaux, 16. Kauffman and Othberg, 2005b to the 1:24,000-scale geologic maps shown in Figure 1. 1995b; Othberg and others, 2005 17. Kauffman and others, 2005a 3. -

Aquatic Biological Communities and Associated Habitats at Selected Sites in the Big Wood River Watershed, South-Central Idaho, 2014

Prepared in cooperation with Blaine County, Trout Unlimited, The Nature Conservancy, and the Wood River Land Trust Aquatic Biological Communities and Associated Habitats at Selected Sites in the Big Wood River Watershed, South-Central Idaho, 2014 Scientific Investigations Report 2016–5128 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover: Big Wood River at Hailey, Idaho, looking downstream from the Bow Bridge with a scientist taking an invertebrate sample. Photograph by Dorene MacCoy, U.S. Geological Survey, September 17, 2014. Aquatic Biological Communities and Associated Habitats at Selected Sites in the Big Wood River Watershed, South-Central Idaho, 2014 By Dorene E. MacCoy and Terry M. Short Prepared in cooperation with Blaine County, Trout Unlimited, The Nature Conservancy, and the Wood River Land Trust Scientific Investigations Report 2016–5128 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2016 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment—visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://store.usgs.gov. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. -

Species Status Assessment Report for the Columbia Spotted Frog (Rana Luteiventris), Great Basin Distinct Population Segment

Species Status Assessment Report for the Columbia Spotted Frog (Rana luteiventris) Great Basin Distinct Population Segment Photo by Jim Harvey Photo: Jim Harvey U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 8 Reno Fish and Wildlife Office Reno, Nevada Suggested reference: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2015. Species status assessment report for the Columbia spotted frog (Rana luteiventris), Great Basin Distinct Population Segment. Reno Fish and Wildlife Office, Reno, Nevada. vii + 86 pp. ii Executive Summary In this Species Status Assessment (SSA), we evaluate the biological status of Columbia spotted frogs (Rana luteiventris) in the Great Basin both currently and into the future through the lens of the species’ resiliency, redundancy, and representation. This SSA Report provides a comprehensive assessment of biology and natural history of Columbia spotted frogs and assesses demographic risks, stressors, and limiting factors. Herein, we compile biological data and a description of past, present, and likely future stressors (causes and effects) facing Columbia spotted frogs in the Great Basin. Columbia spotted frogs are highly aquatic frogs endemic to the Great Basin, northern Rocky Mountains, British Columbia, and southeast Alaska. Columbia spotted frogs in southeastern Oregon, southwestern Idaho, and northeastern and central Nevada make up the Great Basin Distinct Population Segment (DPS; Service 2015, pp. 1–10). Columbia spotted frogs are closely associated with clear, slow-moving streams or ponded surface waters with permanent hydroperiods and relatively cool constant water temperatures (Arkle and Pilliod 2015, pp. 9–11). In addition to permanently wet habitat, streams with beaver ponds, deep maximum depth, abundant shoreline vegetation, and non-salmonid fish species have the greatest probability of being occupied by Columbia spotted frogs within the Great Basin (Arkle and Pilliod 2015, pp. -

OUTFITTER/GUIDE RIVER BOATING APPLICATION TRAINING REQUIREMENTS (FOR OG-11) See Rules for Complete Requirements

OG-5 (10/15) OUTFITTER/GUIDE RIVER BOATING APPLICATION TRAINING REQUIREMENTS (FOR OG-11) See Rules for complete requirements. Unclassified river section qualifications: To qualify as a float boat guide on unclassified rivers and streams, the applicant shall have had one (1) complete trip on each of the rivers applied for under the supervision of a float boat guide licensed for each of those rivers. A completed OG-11 Training Log shall be submitted giving dates, river section, and the signatures of the supervisor, trainee, and licensed outfitter. Classified river section qualifications: A float boat guide on a classified river shall be licensed as a boatman or a lead boatman according to his experience on that specific river. Each float boat trip on a classified river shall have a lead boat operated by a guide licensed as a lead boatman for that specific river and all other boats participating in that trip shall follow the lead boat and shall be operated by a guide licensed as a boatman or a lead boatman for that specific river. (See Rule 040.01) Each training trip means the total section of river as designated by the Board. (See Rules 040, 041, 042 and 059) An applicant for a float boatman license on classified rivers may qualify in one of three ways: a. The guide shall have had three (3) complete float boat trips on each of the classified rivers applied for, under the direct supervision of a float boatman licensed for that river or they shall have had one or more complete float boat trips on each of the classified rivers applied for under the direct supervision of a float boatman licensed for that river with the remaining trip(s) in a boat with no more than one other trainee following a licensed float boatman for that river but they must not have passengers in the boat; or, b. -

12-Month Finding on a Petition to Remove the Bliss Rapids Snail

47536 Federal Register / Vol. 74, No. 178 / Wednesday, September 16, 2009 / Proposed Rules (2) The amount of the allotment for (1) The State has submitted to the claimed during a 2-year period of each of the 50 States and the District of Secretary, and has approved by the availability, beginning with the fiscal Columbia, and for each of the Secretary a State plan amendment or year of the final allotment and ending Commonwealths and Territories (not waiver request relating to an expansion with the end of the succeeding fiscal including the additional amount for FY of eligibility for children or benefits year following the fiscal year. 2009 determined under paragraph under title XXI of the Act that becomes Authority: (Section 1102 of the Social (c)(2)(ii) of this section) is equal to the effective for a fiscal year (beginning Security Act (42 U.S.C. 1302) product of: with FY 2010 and ending with FY (Catalog of Federal Domestic Assistance (i) The percentage determined by 2013); and Program No. 93.778, Medical Assistance dividing the amount in paragraph (2) The State has submitted to the Program) (e)(2)(i)(A) by the amount in paragraph Secretary, before the August 31 (Catalog of Federal Domestic Assistance (e)(2)(i)(B) of this section. preceding the beginning of the fiscal Program No. 93.767, State Children’s Health (A) The amount of the State allotment year, a request for an expansion Insurance Program)) allotment adjustment under this for each of the 50 States and the District Dated: June 19, 2009.