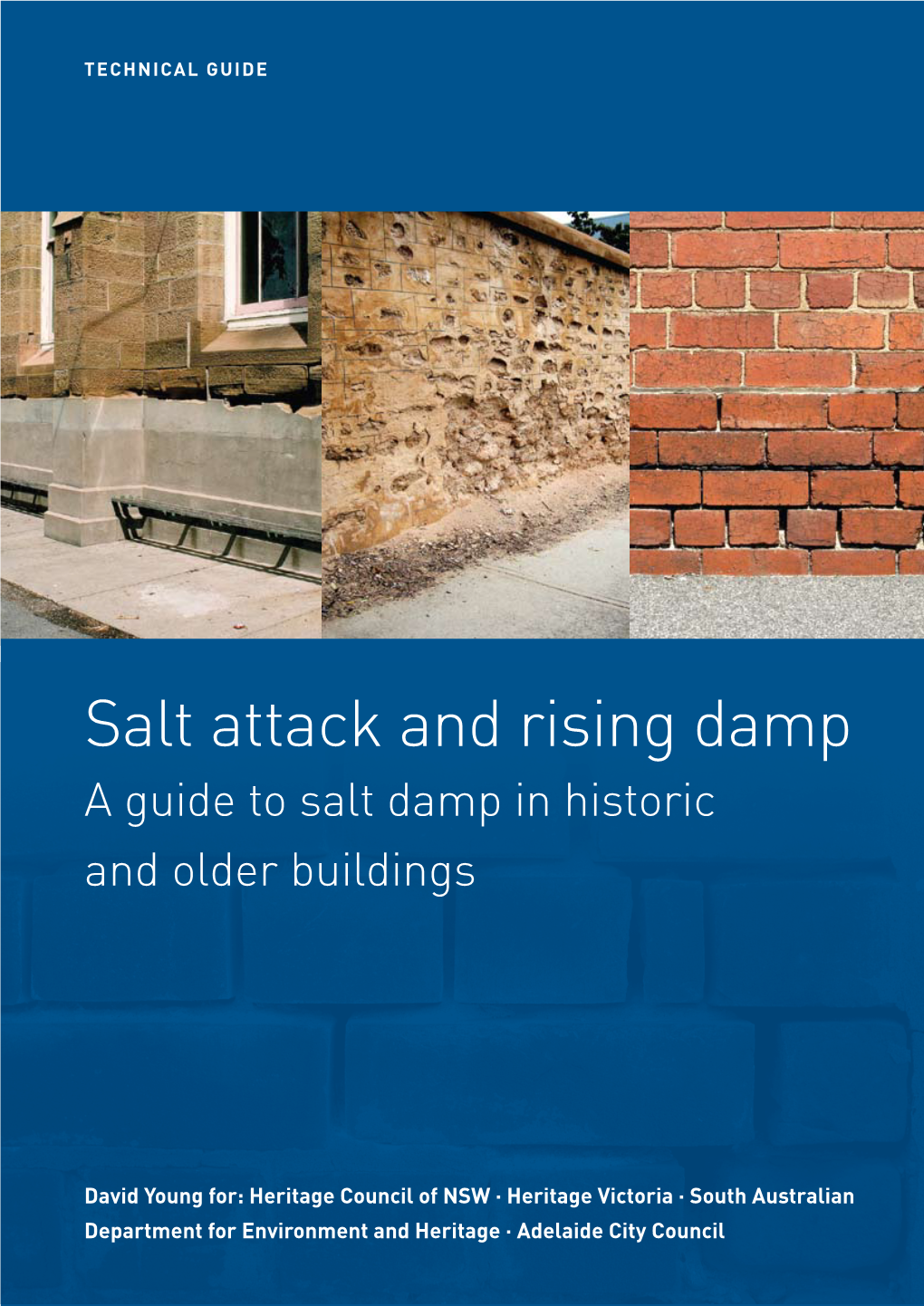

Salt Attack and Rising Damp Technical Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brick Masonry Brick

Brick Masonry Brick • Brick is a basic building unit which is in the form of rectangular block in which length to breadth ratio is 2 but height can be different. • Normal size (nominal size) • 9''×4½" ×3" • Architectural size (Working size) • 81⅟16" x 4⁵⁄₁₆" x 21⅟16" • Brick Masonary The art of laying bricks in mortor in a proper systematic manner gives homogeneous mass which can withstand forces without disintigration, called brick masonary. Terminology: The surfaces of a brick have names: Top and bottom surfaces are beds. Ends are headers and header faces. Sides are stretchers or stretcher faces. Bricks are the subject of British Standard BS 3921. Brick Sizes A standard metric brick has coordinating dimensions of 225 x 112.5 x 75 mm (9''×4½" ×3“) called nominal size and working dimensions (actual dimensions) of 215 x 102.5 x 65 mm (8.5“ * 4 *2.5) called architectural size Brick Sizes Brick Sizes The coordinating dimensions are a measure of the physical space taken up by a brick together with the mortar required on one bed , one header face and one stretcher face. The working dimensions are the sizes to which manufacturers will try to make the bricks. Methods of manufacture for many units and components are such that the final piece is not quite the size expected but it can fall within the defined limits. This can be due to the things like shrinkage, distortion when drying out, firing etc. The difference between the working and coordinating dimensions of a brick is 10mm (0.5“)and this difference is taken up with the layer of mortar into which the bricks are pressed when laying. -

Wall Tiling Installation Guide

Wall Tiling Installation Guide February 2017 1 Important Notes 3 Internal Wall Substrates 4-5 Planning 6 General Information 7-8 Installing: Glass tiles. 9-11 Glass tiles with Painted backs & Protective Layers. Installing: Installing Glass Mosaics. 12-15 Installing Glass & Slate Mosaics. Installing Crackle Glaze tiles. 16-17 Installing Glazed Ceramic & Porcelain tiles. 18-19 Installing Mother of Pearl. 20-21 Installing Floor tiles on a wall. 21 Product Notes. 22 Glossary. 22 Substrate Preparation Guide. 23 Tile Essentials Product Selector – Glazed Wall Tiles. 24-26 Tile Essentials Product Selector – Stone / Slate / Mother of Pearl. 27-28 Tile Essential Product Selector – Glass Wall Tiles. 29-30 Tile Essential Product Selector – Floor Tiles. 30 Sealants and Finishes. 31 2 Important Notes The purpose of this booklet is to outline the basic principles of installing Fired Earth wall tiles. This is intended as a guide, we would always recommend you refer to British Standard BS 5385 Wall and Floor Tiling for more detailed technical information. Prior to installation please ensure the tiles purchased are suitable for the application and thoroughly inspected. Ensure your tiler is aware of the expected finish of the tiles and there are sufficient tiles for the area. The tiles must be well shuffled by drawing tiles from all the boxes. Dry lay an area in suitable light as a final check before installation. For further information or if any doubt exists, please telephone our Technical Department for advice prior to commencing any tiling. Fired Earth have tested our range of adhesives, grout and sealants to ensure compatibility with all of our tiles (see our Product Selector on pages 25 to 31). -

![SP 20 (1991): Handbook on Masonry Design and Construction [CED 13: Building Construction Practices Including Painting, Varnishing and Allied Finishing]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5611/sp-20-1991-handbook-on-masonry-design-and-construction-ced-13-building-construction-practices-including-painting-varnishing-and-allied-finishing-875611.webp)

SP 20 (1991): Handbook on Masonry Design and Construction [CED 13: Building Construction Practices Including Painting, Varnishing and Allied Finishing]

इंटरनेट मानक Disclosure to Promote the Right To Information Whereas the Parliament of India has set out to provide a practical regime of right to information for citizens to secure access to information under the control of public authorities, in order to promote transparency and accountability in the working of every public authority, and whereas the attached publication of the Bureau of Indian Standards is of particular interest to the public, particularly disadvantaged communities and those engaged in the pursuit of education and knowledge, the attached public safety standard is made available to promote the timely dissemination of this information in an accurate manner to the public. “जान का अधकार, जी का अधकार” “परा को छोड न 5 तरफ” Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan Jawaharlal Nehru “The Right to Information, The Right to Live” “Step Out From the Old to the New” SP 20 (1991): Handbook on Masonry Design and Construction [CED 13: Building Construction Practices including Painting, Varnishing and Allied Finishing] “ान $ एक न भारत का नमण” Satyanarayan Gangaram Pitroda “Invent a New India Using Knowledge” “ान एक ऐसा खजाना > जो कभी चराया नह जा सकताह ै”ै Bhartṛhari—Nītiśatakam “Knowledge is such a treasure which cannot be stolen” HANDBOOK ON MASONRY DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION (First Revision) BUREAU OF INDIAN STANDARDS MANAK BHAVAN, 9 BAHADUR SHAH ZAFAR MARG NEW DELHI 110002 SP 20(S&T) : 1991 FIRST PUBLISHED NOVEMBER 1981 FIRST REVISION MARCH 1991 0 BUREAU OF INDIAN STANDARDS 1991 UDC 693 ISBN 81-7061-029-X PRICE Rs 200.00 PRINTED IN INDlA AT KAPOOR ART PRESS, A3813 MAYAPURI, NEW DELHI AND PUBLISHED BY BUREAU OF INDIAN STANDARDS, NEW DELHI 110002 . -

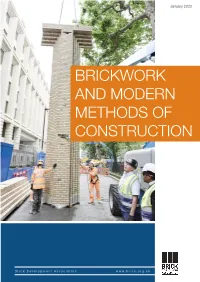

Brickwork and Modern Methods of Construction

January 2020 BRICKWORK AND MODERN METHODS OF CONSTRUCTION Brick Development Association www.brick.org.uk BRICKWORK & MMC 2 Contents Page INTRODUCTION 03 MMC DEFINITIONS 04 HISTORY OF BRICKWORK MMC 05 SLIP PANEL SYSTEMS - INDIVIDUAL SLIPS 06 - PANEL SYSTEMS 07 - RAIL AND TILE 08 PRECAST CONCRETE 09 PRE FABRICATED COMPONENTS 10 ROBOTICS 11 DESIGN & SPECIFICATION 12 REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING 15 SEVERELYBRICKWORK EXPOSED & MMC BRICKWORK 3 INTRODUCTION In construction there is a continuous desire to build projects to a higher quality, on a shorter timescale and at a reduced cost. The government's Construction Sector Deal challenges the industry to reduce construction cost by 1/3 and construction time by 1/2, whilst improving quality. One of the key drivers identified to achieve these targets is the development and expansion of Modern Methods of Construction. Brick manufacturers have been at the forefront of developing MMC systems for several years. Clay brick has undergone a dramatic transformation during the 20th century. From solid wall construction to the modern cavity wall, with improved levels of insulation and reduced water penetration. CAUTION REQUIRED The sector needs to be mindful that during the push for quicker and cheaper we don't compromise the quality of what is built, as has happened with previous attempts to develop MMC. One of the principal benefits of hand laid clay brick is that it has a very long history of quality performance with a large and proven supply chain. Assessing when it is appropriate to use a MMC system, to gain maximum Traditional solid wall construction benefits, has historically been a complex issue. -

Damp-Proofer & Waterproofer

Damp-Proofer & Waterproofer AQUAPRUFE Date: 03 October 2016 Fact Sheet No.: TDS00461 YOUR SMART ADVANTAGES and out of direct sunlight. Protect from frost. For concrete and brick walls & floors TYPICAL PERFORMANCE DATA (Approx.) Can be applied to damp surfaces Application +5°C to +35°C Temperature Brush on Viscosity 4000-9000 MPas USES Drying Time Approx. 24 hours per coat depending Bostik Aquaprufe Damp-Proofer & Waterproofer is a on drying conditions. However flexible, cold applied, odourless, rubber enriched bitumen product always remains tacky emulsion for use both internally and externally. Coverage Floors: 1.25m2 per litre per coat Bostik Aquaprufe Damp-Proofer & Waterproofer provides a highly efficient sandwich damp-proof membrane for floors Walls: 2m2 per litre per coat - Bostik Aquaprufe Damp-Proofer & Waterproofer must be overlaid with a minimum 50mm flooring screed. It also acts Depending on application technique as a waterproofer for walls when plastered or plaster and ambient conditions boarded over. Bostik Aquaprufe Damp-Proofer & Waterproofer must always be covered as it remains tacky. Solvent for Cleaning Warm soapy water whilst still wet Up White spirit when dry PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS Colour Dark Brown, dries black DIRECTIONS FOR USE IMPORTANT: Before using Bostik Aquaprufe Damp-Proofer Form A structured liquid & Waterproofer refer to the relevant Health & Safety Data Sheet, available at www.bostik.co.uk. Specific Gravity 1.0 approx. PREPARATION Composition Bitumen and rubber latex aqueous 1. Bostik Aquaprufe Damp-Proofer & Waterproofer dispersion should be applied to slightly damp, not wet surfaces. Do not apply outdoors when raining or if there is risk of Product Codes 30812206 2.5 Litre x 6 rain, frost, fog, or dew before Bostik Aquaprufe Damp- 30812207 5 Litre x 4 Proofer & Waterproofer has dried. -

Omnimat Flexible, Damp-Resistant And

WD OMNIMAT DECOUPLING MEMBRANE FLEXIBLE, DAMP-RESISTANT AND WATERPROOF MAT, WITH ACCESSORIES FOR LAYING UNDER TILES Characteristic product properties n Very good chemical resistance. n Suitable for surfaces that are sensitive to moisture, such as wood, plasterboard and plaster coatings. n Only a very thin 0.4 mm layer is required. n Can be used on walls and floors. n Suitable for interior and exterior use under certain conditions. Applications Using WD omnimat and these accessories ensures a perfect damp-proof seal and decoupling under tiles and natural stone. The mat has very good chemical resistance and can easily be used on surfaces that are sensitive to moisture, such as wood, plasterboard and plaster coatings. Showers, bathrooms, sports facilities, spa facilities and areas affected by intense moisture are just a few examples of how it can be used. If you would like to use it in swimming pools and other specific applications, we recommend that you contact us. Appropriate surfaces n Anhydrite (white powder adhesive) n Approved fibre-plaster boards n Brick (white powder adhesive) n Existing tiles n Pressed wood fibres/underlayment n Concrete n Multiplex wood n Concrete blocks n Lime-cement coating n Cellular concrete n Sand-limestone n Cement coating n Ceramic interior bricks n Cement screed n Cork n Cement screed with underfloor heating n O-BOARD n Electric underfloor heating n Polystyrene board n Epoxy coating n Decorative coating n Plaster coating (white powder adhesive) n Silicate board n Plaster blocks (white powder adhesive) n Stone carpet n Plasterboard n Paint n Approved fibre-cement boards n Wall heating For specific details, please refer to our “General instructions for surfaces”. -

Thermal and Moisture Protection: Keeping the Weather out Internet Course

Rich Text Editor,editor1 http://www.licensetobuild.com/web-class/controls/?mt=coursemanagem... Thermal and Moisture Protection: Keeping the Weather Out Internet Course Learning Objectives Summarize the key elements (either natural or mechanical) of a properly ventilated structure. List and describe at least three specific installation techniques and/or materials that contribute to a properly constructed roof system. Outline at least one design strategy based on "best practices" for the construction of buildings in areas with high humidity. Identify and implement proven methods that will effectively divert moisture from the foundation of a structure. Keeping the Weather Out Protecting buildings from weather and moisture related problems is important for all building professionals. In areas of high humidity, (and ALL Florida counties are considered "warm humid counties" by the Florida Building Code: Energy Conservation 301.2), it is even more important that builders, their employees, and their subcontractors use “Best Practice” procedures to carefully install thermal and weather resistant components. Because of the potential for loss due to consumer complaints and claims, it makes sense for contractors to be trained in moisture control for the homes and buildings they are constructing or renovating. Major performance objectives. One objective of a building envelope system is to provide moisture control. Construction of a building envelope system needs to incorporate methods and materials that prevent or minimize the impact of moisture intrusion. The photo below shows typical damage caused by poorly installed or maintained building envelope components! Too often, exterior shells are simply sealed up without regard for proper installation of house- wraps, flashing and ventilation. -

Lime Plaster & Plaster Lath for Damp Buildings

Lime Plaster & Plaster Lath for Damp Buildings Lime Plaster & Plaster Lath for Damp Buildings Surveying for Damp Issues with Historic Buildings. Buildings fall into two categories for the purposes of surveying for damp: I. Modern buildings built with a damp proof course and barriers to rainwater penetration. II. Old buildings built prior to mid to late 19th century depending upon the region of the country. Old buildings relied on the walls breathing and shedding moisture before damp became a problem. Damp Proofing Old Buildings In old buildings, walls were built to such a thickness that normally damp would not penetrate to the inside. The joints were always of lime mortar or earth and were more porous than the building’s structural elements comprising brick, stone etc. Consequently the joints would drain and shed water by evaporation, therefore not allowing damage to these structural elements. The joints were the sacrificial element of the building. Because lime and earth mortars are so porous, timber in contact with these mortars is less prone to decay than when bedded in cement mortar. Historic houses, when built, were able to breathe and shed water. They were also heated by coal or log fires in an open fireplace which promoted rapid air changes by way of air being drawn out through the chimney. Windows and doors were not sealed as they are today allowing air movement into and out of the building. Internal finishes were lime washed which allowed surfaces to breathe and, although it would discolour when damp, it would not peal off the wall like wall paper nor blister like modern paint. -

Model Building Bye Laws Brought out in 2004

,2016 Revised and Published in 2016. © Ministry of Urban Development, Government of India, 2016 Material from this publication may be used for educational or other purposes with due credits. Overall guidance Sh. Neeraj Mandloi, IAS. Joint Secretary, Ministry of Urban Development, Govt. of India Technical Team TCPO Late Sh. J.B. Kshirsagar. Former Chief Planner Sh. R. Srinivas TCP (Head), MUT Division Sh. Sudeep Roy Assistant TCP Ms. D Blessy Assistant TCP Stakeholders in Consultative Workshop Central Governments agencies/ Institutes: National Disaster Management Authority Bureau of Indian Standards National Building Construction Corporation National Remote Sensing Centre Delhi Development Authority National Capital Region Planning Board Indian Institute of Public Administration Municipal Corporation of Delhi (South) Housing and Urban Development Corporation Schools of Planning and Architecture State Government Departments State Town and Country Planning Departments Selected Urban Development Authorities Selected Urban Local Bodies. Associations like CREDAI and NAREDCO Expert Review Prof. Dr. PSN Rao Chairman, Delhi Urban Arts Commission. New Delhi PRELUDE Building Bye-Laws are legal tools used to regulate coverage, height, building bulk, and architectural design and construction aspects of buildings so as to achieve orderly development of an area. They are mandatory in nature and serve to protect buildings against fire, earthquake, noise, structural failures and other hazards. In India, there are still many small and medium sized towns which do not have building bye-laws and in the absence of any regulatory mechanism, such towns are confronted with excessive coverage, encroachment and haphazard development resulting in chaotic conditions, inconvenience for the users, and disregard for building aesthetics, etc. -

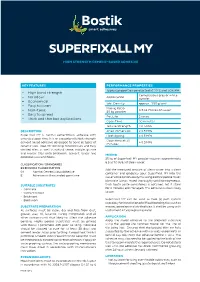

Superfixall My

SUPERFIXALL MY HIGH STRENGTH CEMENT-BASED ADHESIVE KEY Features Performance Properties Typical properties conducted at 22oC and 50% RH – High bond strength Cementitious grey or white Appearance – No odour powder – Economical Wet Density approx. 1.55 g/cm3 – Easy to clean Mixing Ratio 6.5 to 7 litres of water – Non-toxic 25 kg powder – Easy to spread Pot Life 2 hours – Thick and thin bed applications Open Time 30 minutes Tensile Strength ≥ 0.5 MPa DESCRIPTION After Immersion ≥ 0.5 MPa Superfixall MY is normal cementitious adhesive with Heat Ageing ≥ 0.5 MPa extended open time. It is an exceptionally high strength Open time at 30 cement based adhesive developed to bond all types of ≥ 0.5 MPa minutes ceramic tiles. Ideal for bonding monocottura and fully vitrified tiles, as well as natural stone, marble, granite and mosaic tiles onto brickwork, cement render and MIXING concrete walls and floors. 25 kg of Superfixall MY powder requires approximately 6.5 to 7.0 litres of clean water. CLASSIFICATION / STANDARDS BS EN12004 CLASSIFICATION Add the measured amount of clean water into a clean C1 Normal Cementitious Adhesive container and gradually pour Superfixall MY into the E Adhesive with extended open time water while continuously mix using electric paddle mixer. Eliminate lumps. Mixed thoroughly until homogeneous, SUITABLE SUBSTRATES thick tooth paste consistency is obtained. Let it stand • Concrete for 2 minutes and mix again. The adhesive is now ready • Cement render to use. • Brickwork • Blockwork Superfixall MY can be used as two (2) part system especially for installation of difficult bonding tiles such as SUBstrate preparation mosaic, porcelain and vitrified tiles. -

MASON (Building Constructor)

CURRICULUM FOR THE TRADE OF MASON (Building Constructor) UNDER APPRENTICESHIP TRAINING SCHEME (ATS) GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF SKILL DEVELOPMENT & ENTREPRENURESHIP DIRECTORATE GENERAL OF TRAINING 1 CONTENTS Sl. No. Topics Page No. 1. Acknowledgement 03 2. Background 04 – 05 2.1 Apprenticeship Training under Apprentice Act 1961 2.2 Changes in Industrial Scenario 2.3 Reformation 3. Rationale 06 4. Job roles: reference NCO 07 5. General Information 08 6. Course structure 09 – 10 7. Syllabus 11 – 27 7.1 Basic Training 7.1.1 Detail syllabus of Core Skill A. Block-I (Engg. drawing & W/ Cal. & Sc.) B. Block-II (Engg. drawing & W/ Cal. & Sc.) 7.1.2 Detail syllabus of Professional Skill & Professional Knowledge A. Block – I B. Block – II 7.1.3 Employability Skill 7.1.3.1 Syllabus of Employability skill A. Block – I B. Block – II 7.2 Practical Training (On-Job Training) 7.2.1 Broad Skill Component to be covered during on-job training. A. Block – I B. Block – II Assessment Standard 28 – 30 8.1 Assessment Guideline 8. 8.2 Final assessment-All India trade Test (Summative assessment) 9. Further Learning Pathways 31 2 10. Annexure-I – Tools & Equipment for Basic Training 32 – 35 11. Annexure-II – Infrastructure for On-Job Training 36 12. Annexure-III - Guidelines for Instructors & Paper setter 37 1. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The DGT sincerely express appreciation for the contribution of the Industry, State Directorate, Trade Experts and all others who contributed in revising the curriculum. Special acknowledgement to the following industries/organizations who have contributed valuable inputs in revising the curricula through their expert members: 1. -

10 Year Solution – Exterior Walls

Summary - 10 year solution – exterior walls Remove plaster up to 1.2m above DPC line Re-glue brittle bricks with Dampsure GlueBack Drill 12mm dia holes one brick above highest ground level, min 100mm apart Inject chemical DPC Cream stopping future rising damp Waterproof wall where plaster was removed with Dampsure Dampcrete47 – prevent retained moisture to permeate into new plaster Apply mixture of Bonding Liquid with river sand to waterproofed wall Re-plaster with Dampsure Plastersure Plaster Additive – capillaries in plaster are rubberised and Salt Neutraliser prevents forming of efflorescence (bubbling of paint) Put a Dampcrete47 waterproofing sock onto new plaster Paint 28 days after remedial work was done The diagram below depicts the process to be followed: Dampsure is achieving phenomenal damp proofing results with its 10 year rising damp solution. This recipe has been designed in Europe to fix rising damp problems. This recipe is long lasting and has stood the test of time. Dampsure has had no comebacks or failures on the above recipe. Dampsure Cnr Hendrik Potgieter & Gordon rd, Florida 083 501 0060 Recipe - Rising damp – 10 year solution Preparation Warning!! before You are going to work with moisture and products that may damage floors and furniture. starting with Cover all tile floors, paving etc with plastic to minimize moisture and or chemical damage project and or water ingress Tape aluminium window and door frames with yellow aluminium tape Cover window panes with plastic Tape all pipes and fittings on walls Close all electrical points with waterproofing tape or plastic Remove all skirting and fixtures that are in the area that will be treated Identify the areas where water pipes and electrical wires might be damaged by drilling or chipping, mark these area and handle these areas with care.