Nipmuc Brief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Ethno-Historical Response to the October 5, 2007 Memorandum

An Ethno-historical Response to the October 5, 2007 Memorandum Submitted by Hobbs, Straus, Dean & Walker to the National Indian Gaming Commission on Behalf of the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation of Kansas. By James P. Lynch Historical Consulting and Research Services LLC On Behalf of Dekalb County Taxpayers Against the Casino (DCTAC) December 2, 2007 1 Table of Contents. Introduction…………………………………………………..4. A Response To: I. The Shab-en-nay Indian Reservation, Established July 29, 1829, by the Treaty of Prairie du Chien for a Band of Potawatomi Indians in Illinois, Has Never Been Disestablished, and Still Exists Today…………………………….….8. A. The Early Potawatomi Treaties…...…………………………..…8. B. Chief Shab-eh-nay Was an Important Potawatomi Leader and a Hero to the Local White Settlers; His Band Received the Reservation in Consideration of Shab-eh-nay’s Services to the U.S. and the White Community.………….………………..13. 1. Early Days.……………………………………………….13. 2. The 1829 Treaty..………………………………………...21. 3. The 1833 Treaty..………………………………………...34. 4. The 1846 Treaty..………………………………………....46. C. Commissioner of Indian Affairs Ruling of Abandonment in 1848, and Public Sale of the Shab-en-nay Reservation in 1849....……………………………………………………….…52. 1. Commissioner of Indian Affairs Ruling of 2 Abandonment.………………………………………...…52. 2. The General Land Office Public Sale in 1849.………….55. A Response To: II. At the Time the Shab-eh-nay Reservation Was Established by the 1829 Treaty the Potawatomis Owned Treaty-Recognized Title to the Land Surrounding that Reservation..……...………...……57. -

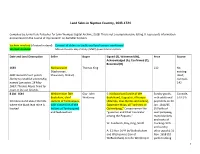

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country.Pdf

Land Sales in Nipmuc Country, 1643-1724 Compiled by Jenny Hale Pulsipher for John Wompas Digital Archive, 2018. This is not a comprehensive listing. It represents information encountered in the course of my research on Swindler Sachem. Sachem involved (if noted in deed) Consent of elders or traditional land owners mentioned Woman involved Massachusetts Bay Colony (MBC) government actions Date and Land Description Seller Buyer Signed (S), Witnessed (W), Price Source Acknowledged (A), ConFirmed (C), Recorded (R) 1643 Nashacowam Thomas King £12 No [Nashoonan, existing MBC General Court grants Shawanon, Sholan] deed; liberty to establish a township, Connole, named Lancaster, 18 May 142 1653; Thomas Noyes hired by town to lay out bounds. 8 Oct. 1644 Webomscom [We Gov. John S: Nodowahunt [uncle of We Sundry goods, Connole, Bucksham, chief Winthrop Bucksham], Itaguatiis, Alhumpis with additional 143-145 10 miles round about the hills sachem of Tantiusques, [Allumps, alias Hyems and James], payments on 20 where the black lead mine is with consent of all the Sagamore Moas, all “sachems of Jan. 1644/45 located Indians at Tantiusques] Quinnebaug,” Cassacinamon the (10 belts of and Nodowahunt “governor and Chief Councelor wampampeeg, among the Pequots.” many blankets and coats of W: Sundanch, Day, King, Smith trucking cloth and sundry A: 11 Nov. 1644 by WeBucksham other goods); 16 and Washcomos (son of Nov. 1658 (10 WeBucksham) to John Winthrop Jr. yards trucking 1 cloth); 1 March C: 20 Jan. 1644/45 by Washcomos 1658/59 to Amos Richardson, agent for John Winthrop Jr. (JWJr); 16 Nov. 1658 by Washcomos to JWJr.; 1 March 1658/59 by Washcomos to JWJr 22 May 1650 Connole, 149; MD, MBC General Court grants 7:194- 3200 acres in the vicinity of 195; MCR, LaKe Quinsigamond to Thomas 4:2:111- Dudley, esq of Boston and 112 Increase Nowell of Charleston [see 6 May and 28 July 1657, 18 April 1664, 9 June 1665]. -

Blackstone River Valley National Historical Park

National Park Service Blackstone River Valley U.S. Department of the Interior National Historical Park Dear Friends – Welcome to the first newsletter for your new Blackstone River Valley National Historical Park. As of December 19, 2014, Blackstone became the 402nd unit of the National Park Service. What an accomplishment! Thank you to everyone who made this park a reality. The National Park Service is honored to be able to tell the story of “the Birthplace of America’s Industrial Revolution,” here, in the Blackstone Valley. While the park has been legislatively established, there is still some work to do. First and foremost, the National Park Service (NPS) is working on drawing the park boundary. We are meeting with state government agencies, nonprofit organizations, municipalities, stakeholders, community members and volunteers to help us define this boundary. We would love your input and hope to hear from you. Though we don’t yet have an official boundary, NPS Rangers are out in the Valley this summer. We have rangers supporting summer camps, giving Walkabouts, attending events, and meeting visitors at important sites. We are working on publishing outreach materials and Jr. Ranger books. National Park Passport stamps will be coming soon! On behalf of all of us that have the honor to work for the NPS, we appreciate your support in our mission to create a world-class National Park in the Blackstone River Valley. I’m excited to be on this journey with you. Sincerely, Meghan Kish Meghan Kish Superintendent Blackstone River Valley National Historical Park Meet the Staff Meghan Kish is the Superintendent for Blackstone River Valley National Historical Park, New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park and Roger Williams National Memorial. -

Vital Allies: the Colonial Militia's Use of Indians in King Philip's War, 1675--1676

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Master's Theses and Capstones Student Scholarship Spring 2011 Vital allies: The colonial militia's use of Indians in King Philip's War, 1675--1676 Shawn Eric Pirelli University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Pirelli, Shawn Eric, "Vital allies: The colonial militia's use of Indians in King Philip's War, 1675--1676" (2011). Master's Theses and Capstones. 146. https://scholars.unh.edu/thesis/146 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses and Capstones by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VITAL ALLIES: THE COLONIAL MILITIA'S USE OF iNDIANS IN KING PHILIP'S WAR, 1675-1676 By Shawn Eric Pirelli BA, University of Massachusetts, Boston, 2008 THESIS Submitted to the University of New Hampshire in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts In History May, 2011 UMI Number: 1498967 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 1498967 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC. -

A Grammar of the Nipmuck Language

A GRAMMAR OF THE NIPMUCK LANGUAGE BY HOLLY SUZANNE GUSTAFSON ATbesis Submitted to the Faceof Graduate Studies In Partial Fulnlment of the Requirements For tbe Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Deparament of Linguistics University of Manitoba Winnipeg, Manitoba O Copyright by HoUy Gustafson 200 National Library Bibliothéque nationale 1+1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellingîm Ottawa ON KlAûN4 O(tawaON K1AW canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sel1 reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/fih, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copy~@tin this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts f?om it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. THE UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES +te*+ COPYRIGHT PERMISSION PAGE A Grammlr of the Nipmach Languagc BY HoUy Suzanne Gartrfson A ThesiJ/Prricticarn sabmitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of &Manitobain partiai fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of HOLLY SUZANNE GUSTAFSON O 2000 Permission has ben grrnted to the Libnry of The University of Manitoba to Iend or seii copies of this thesidpncticum, to the National Librrry of Caoadi ta microfilm this thesidpracticum and to lend or sell copies of the film, and to Dissertations Abstracts International ta publish an abstract of this thesis/pmcticum. -

NATIVE AMERICANS in MASSACHUSETTS: NEW HOMECOMINGS and ONGOING DISPLACEMENTS by J

NATIVE AMERICANS IN MASSACHUSETTS: NEW HOMECOMINGS AND ONGOING DISPLACEMENTS By J. Cedric Woods, Director, Institute for New England Native American Studies, UMass Boston hat is now the Commonwealth of For these people, catastrophic population loss followed Massachusetts, was, is and always will sustained contact with Europeans due to disease, Wbe Indian Country. The names used enslavement and warfare, but nevertheless Native for the inhabitants and settlements of this land have Peoples are still very much present in Massachusetts. changed over the last 10,000 years, but thousands of The trends of loss and survival would continue, Indigenous Peoples from the Massachusett, Nipmuc although punctuated by periods of stabilization, and Wampanoag tribes historically resided in the areas throughout much of the 17th century. The 18th century on which this section focuses: the town of Aquinnah brought new challenges as the ongoing entanglement on Martha’s Vineyard (what Natives call Noepe) and of Natives in European, and later American, military the Greater Boston region (Figure 4.1). conflicts and physically dangerous employment (like FIGURE 4.1 Several distinct Native Peoples inhabited what is now Massachusetts and points south. Tribal territories of Southern New England. Around 1600. Author: Nikater, adapted to English by Hydrargyrum. Retrieved from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tribal_Territories_Southern_New_England.png#/media/File:Tribal_Territories_ Southern_New_England.png 41 NATIVE AMERICANS IN MASSACHUSETTS whaling) led to chronically disproportionate loss For those unfamiliar with ongoing trends in Indian of life, particularly of Native men (Figure 4.2). The Country demographics, a look at the most commonly 19th century saw efforts by the Commonwealth to used Census data for the Massachusetts Native politically dismantle Native communities (whether population may be deceiving. -

The Easton Family of Southeast Massachusetts: the Dynamics Surrounding Five Generations of Human Rights Activism 1753--1935

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2006 The Easton family of southeast Massachusetts: The dynamics surrounding five generations of human rights activism 1753--1935 George R. Price The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Price, George R., "The Easton family of southeast Massachusetts: The dynamics surrounding five generations of human rights activism 1753--1935" (2006). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 9598. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/9598 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission ___________ Author's Signature: Date: 7 — 2 ~ (p ~ O b Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. 8/98 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. -

King Philip's Ghost: Race War and Remembrance in the Nashoba Regional School

King Philip’s Ghost: Race War and Remembrance in the Nashoba Regional School District By Timothy H. Castner 1 The gruesome image still has the power to shock. A grim reminder of what Thoreau termed the Dark Age of New England. The human head was impaled upon a pole and raised high above Plymouth. The townspeople had been meeting for a solemn Thanksgiving filled with prayers and sermons, celebrating the end of the most brutal and genocidal war in American history. The arrival and raising of the skull marked a symbolic high point of the festivities. Many years later the great Puritan minister, Cotton Mather, visited the site and removed the jaw bone from the then exposed skull, symbolically silencing the voice of a person long dead and dismembered. There the skull remained for decades, perhaps as long as forty years as suggested by historian Jill Lepore. Yet while his mortal remains went the way of all flesh, Metacom or King Philip, refused to be silenced. He haunts our landscape, our memories and our self-conception. How might we choose to live or remember differently if we paused to learn and listen? For Missing Image go to http://www.telegram.com/apps/pbcsi.dll/bilde?NewTbl=1&Site=WT&Date=20130623&Category=COULTER02&Art No=623009999&Ref=PH&Item=75&Maxw=590&Maxh=450 In June of 2013 residents of Bolton and members of the Nashoba Regional School District had two opportunities to ponder the question of the Native American heritage of the area. On June 9th at the Nashoba Regional Graduation Ceremony, Bolton resident and Nashoba Valedictorian, Alex Ablavsky questioned the continued use of the Chieftain and associated imagery, claiming that it was a disrespectful appropriation of another groups iconography which tarnished his experience at Nashoba. -

Here in the in This Canal Walk Series (1-5), Enjoy a Guided Walk to Explore Blackstone River Valley National Heritage Corridor

Blackstone River Valley National Heritage Corridor NNUA A L h t 5 2019 GO! for a walk, a tour, a bike ride, a paddle, a boat ride, a special event or harvest experience – all in the month of September in the wonderful Blackstone River Valley National Heritage Corridor. Proudly sponsored by GO! Table of Contents Welcome ........................ 2-3 Map ............................... 4 Listing of Experiences & Events ...................... 8-42 Be a GearHead! ................ 23 VIP Program .................... 44 Page 17 Photo Contest ................. 44 Support the Blackstone Heritage Corridor ............ 45 Online Shop .................... 45 SEPTEMBER 2019 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Page 32 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 Visit us at BlackstoneHeritageCorridor.org for more free, guided experiences and special events (some may Page 36 charge fees)! Updated daily. Page 37 670 Linwood Avenue Whitinsville, MA 01588 508-234-4242 BlackstoneHeritageCorridor.org Cover photo by Tracy Torteson ©2019 Blackstone Heritage Corridor, Inc. Page 42 Table of Contents 1 We welcome you One valley…One environment… to September in the One history…All powered by the Blackstone River! Blackstone So nationally significant, it was named the Blackstone River Valley National Heritage Heritage Corridor! Corridor. So important to the American identity, it was designated the Blackstone It’s all water powered! River Valley National Historical Park. The Blackstone River Valley National Heritage Corridor is most notably known as the Birthplace of the American Industrial Revolution and the first place of tolerance and diversity in the country. In the fall, its many other attributes come vividly into focus as the crispness of autumn grows from the last warmth of summer. -

American Tri-Racials

DISSERTATIONEN DER LMU 43 RENATE BARTL American Tri-Racials African-Native Contact, Multi-Ethnic Native American Nations, and the Ethnogenesis of Tri-Racial Groups in North America We People: Multi-Ethnic Indigenous Nations and Multi- Ethnic Groups Claiming Indian Ancestry in the Eastern United States Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophie an der Ludwig‐Maximilians‐Universität München vorgelegt von Renate Bartl aus Mainburg 2017 Erstgutachter: Prof. Berndt Ostendorf Zweitgutachterin: Prof. Eveline Dürr Datum der mündlichen Prüfung: 26.02.2018 Renate Bartl American Tri-Racials African-Native Contact, Multi-Ethnic Native American Nations, and the Ethnogenesis of Tri-Racial Groups in North America Dissertationen der LMU München Band 43 American Tri-Racials African-Native Contact, Multi-Ethnic Native American Nations, and the Ethnogenesis of Tri-Racial Groups in North America by Renate Bartl Herausgegeben von der Universitätsbibliothek der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Geschwister-Scholl-Platz 1 80539 München Mit Open Publishing LMU unterstützt die Universitätsbibliothek der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München alle Wissenschaft ler innen und Wissenschaftler der LMU dabei, ihre Forschungsergebnisse parallel gedruckt und digital zu veröfentlichen. Text © Renate Bartl 2020 Erstveröfentlichung 2021 Zugleich Dissertation der LMU München 2017 Bibliografsche Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografe; detaillierte bibliografsche Daten sind im Internet abrufbar über http://dnb.dnb.de Herstellung über: readbox unipress in der readbox publishing GmbH Rheinische Str. 171 44147 Dortmund http://unipress.readbox.net Open-Access-Version dieser Publikation verfügbar unter: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bvb:19-268747 978-3-95925-170-9 (Druckausgabe) 978-3-95925-171-6 (elektronische Version) Contents List of Maps ........................................................................................................ -

An Ethno-Historical Response to the Submittal to the National Indian Gaming Commission by Dickson Wright LLC

An Ethno-historical Response to the Submittal to the National Indian Gaming Commission by Dickson Wright LLC. on Behalf of the Dekalb County, Illinois Executive Board. By James P. Lynch Historical Consulting and Research Services December 2, 2007 Table of Contents Introduction ………………………………………...3. I. Comments: “The Tribal Parcel” ……………………5. II. Comments: “The United States Has Never Formally Determined the Legal Land Status for the Shab-en-nay Reserve ……………………………………………12. A. “The Leshy Letter”……..……………………………..20. B. “The Olsen Letter”...…..………………………………33. III. Comments: “The Shab-eh-nay Reserve May Constitute Unextinguished Indian Title But Has Never Enjoyed Reservation Status”…..………………………………....33. A. “IGRA’s Definition of ‘Indian Lands’..…...………….33. B. “Relevant Case Law”..……....………………………..34. C. “Language in the Treaty of Prairie du Chien”..……….34. D. “Treaties Creating Permanent Indian Reservations”.….……………………………………35. IV. Comments: “Conclusion”...….………………………….35. Appendix 1 Vitae of James P. Lynch...…………………………43. Appendix II. Supporting Documentary Exhibits ……………..50. 2 Introduction The principle issue at hand is to determine whether the 128 acres of land, and by implication the entire 1,280 acres of land consisting of the original two sections of land “reserved, for the use” of Shabenay and his band located within Shabbona Township, Dekalb County, Illinois, are “Indian lands” as defined by 25 USC 2704 (4). The 128 acres of land are currently held in fee-simple title by the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation. In its October 1, 2007 submission to the National Indian Gaming Commission,1 (NIGC), Dickenson Wright LLC. by Dennis J. Whittlesey (the Firm), representing the Executive Board of Dekalb County Illinois, opines that the lands in question are not a permanently established, treaty- recognized Indian reservation as claimed by the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation.2 Instead, the Firm claims that the lands in question constitute “Indian lands” upon which Indian title was never extinguished. -

Tribes in Massachusetts

Tribes in Massachusetts The town of Brookline is located on the tribal homelands of the Massachusett people. We acknowledge the continuing presence of the Massachusett, and the neighboring Wampanoag and Nipmuc peoples. We also recognize the Indigenous peoples represented in the town’s residents. There are two federallyrecognized tribes within Massachusetts: the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) and the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribes. Massachusett at Ponkapoag The Massachusett tribe are the descendants of the original people that the English invaders first encountered in what is now the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Tribal members continue to survive as Massachusett people through the retention of their oral traditions. Theirs is the Indigenous nation from whom the present-day Commonwealth of Massachusetts took its name. Wampanoag The Wampanoag territory is in southeastern Massachusetts including Cape Cod and the islands and extends into eastern Rhode Island. The Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) received Federal Acknowledgement as an Indian Tribe in 1987, creating a government-to-government relationship with the U.S. government. Currently 1364 members are enrolled, of which 417 live on Martha’s Vineyard, with the remainder living throughout Massachusetts and other states. The Mashpee Wampanoag were re-acknowledged as a federally recognized tribe in 2007. In 2015, the federal government declared 150 acres of land in Mashpee and 170 acres of land in Taunton as the Tribe’s initial reservation, on which the Tribe can exercise its full tribal sovereignty rights. The Mashpee tribe currently has approximately 2,600 enrolled citizens. Nipmuc Nation The Nipmuc Indians are the tribal group occupying the central part of Massachusetts, northeastern Connecticut and northwestern Rhode Island.