In Search of Holmes from Within

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GET BETTER FASTER: the Ultimate Guide to the Practice of Retrospectives

GET BETTER FASTER: The Ultimate Guide to the Practice of Retrospectives www.openviewlabs.com INTRODUCTION n 1945, the managers of a tiny car manufacturer in Japan took I It can cause the leadership team to be trapped inside a “feel-good stock of their situation and discovered that the giant firms of the bubble” where bad news is avoided or glossed over and tough U.S. auto industry were eight times more productive than their issues are not directly tackled. This can lead to an evaporating firm. They realized that they would never catch up unless they runway; what was assumed to be a lengthy expansion period can improved their productivity ten-fold. rapidly contract as unexpected problems cause the venture to run out of cash and time. Impossible as this goal seemed, the managers set out on a path of continuous improvement that 60 years later had transformed When done right, the retrospective review can be a powerful their tiny company into the largest automaker in the world and antidote to counteract these tendencies. driven the giants of Detroit to the very brink of bankruptcy. In that firm—Toyota—the commitment to continuous improve- This short handbook breaks down the key components of the ment is still a religion: over a million suggestions for improvement retrospective review. Inside you will learn why it is important, are received from their employees and dealt with each year. find details on how to go about it, and discover the pitfalls and difficulties that lie in the way of conducting retrospectives The key practice in the religion of continuous improvement is successfully. -

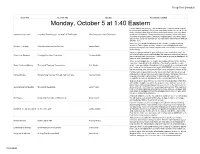

Download Deep Dive Schedule

Deep Dive Schedule Track Title Session Title Speaker Session Description Monday, October 5 at 1:40 Eastern "As the Father has sent me, I am sending you." How can you get out of the box of your building? Go to your community and meet a need. Create family fun days. Host special events and attract those in your city. Have Community Outreach Creatively Reaching Out: Go And Tell The People Miss PattyCake (Jean Thomason) a concert/movie/picnic. Reach into homes via media. Partner with other churches for greater impact. Become a brighter light in your area. Make and execute a plan for outreach so you can share God's big love with big and little lives. Have you ever wondered what goes into effective, creative teaching sessions? Take a journey inside Justyn's successful playbook as he Creative Teaching A Creative Process You Can Use Justyn Smith shares how anyone can create a system and environment of creativity in their ministry. Have you always wanted to give writing your own curriculum a try? Are you tired of using up your entire budget on expensive curriculum that you Curriculum Blueprint Creating Your Own Curriculum Corinne Noble have to heavily edit every week? Find out how to go from a blank page of paper to a full curriculum series. There is nothing quite like seeing the joy in a preschooler's face as they experience something for the first time. The joy of seeing them learn Early Childhood Ministry The Joy Of Teaching Preschoolers B.A. Snider about Jesus and laying a foundation for their growth in a relationship with the Creator of the universe is, in a word, AWESOME! Join me for some tips on teaching your young ones in this crazy, yet joyous, season of life. -

Oxford Lecture 1 - Final Master

OXFORD LECTURE 1 - FINAL MASTER HOW TO GROW A CREATIVE BUSINESS BY ACCIDENT The legendarily bullish film director Alan Parker once adapted Shaw's famous dictum about the academic profession - "those who can, do. Those who can't teach." So far so familiar. And to many in this room, no doubt, so annoying. But he went on: "those who can't teach, teach gym. And those who can't teach gym, teach at film school." I appreciate that Oxford is not a film school, though it has a more distinguished record than any film school for supplying the talent that has fuelled the British film and TV industries for almost a century - on and off camera. Writers like Richard Curtis, who brought us 4 Weddings and a Funeral, Love Actually, The Vicar of Dibley and Blackadder; or The Full Monty and Slumdog Millionaire scribe Simon Beaufoy; directors of the diversity of Looking for Eric's Ken Loach and 24 Hour Party People's Michael Winterbottom; writer/directors like Monty Python's Terry Jones and the Thick of It's Armando Iannucci; actors and performers ranging from Hugh Grant to Rowan Atkinson; and broadcasting luminaries like the BBC's Director General Mark Thompson and News International's very own Rupert Murdoch. So, Oxford has been a pretty efficient film and TV school, without even trying. And perhaps that is Parker's point. Can what passes for creativity in film and TV ever really be taught? But here in my capacity as News International Visiting Professor of Broadcast Media (or if you prefer an acronym, NIVPOB - the final M is silent) I may be even further down Parker's food chain. -

PO BOX 11 Informs Readers of News, Summer 2011 PO BOX 11 Events and People Who Enhance Recovery

alumni news & views PO BOX 11 informs readers of news, SUMMER 2011 PO BOX 11 events and people who enhance recovery. At home and at work Alum finds inspiration through service At age 33, Ben B. became a stay-at-home dad. Before he knew it, his alcohol consumption escalated, turning him into the dad he never wanted to be. Too drunk to take his three-year-old daughter to swimming lessons, he’d trek with her instead to the liquor store or plop her in front of the television for hours. And there were times when he picked her up from play dates with alcohol on his breath. He knew, deep down, he needed help. He called Hazelden. “I was honest about my drinking for the first time. Something happens when you’re honest,” recalls Ben. “I remember telling the counselor I’d do anything he said—I’d wear red clown shoes and jump up and down if I could take a shower in the morning without, halfway through, wondering what I was going to drink and how I was going to hide it.” “Treatment allowed me to draw a line in the sand—to say, ‘From this point forward, things are going to be different.’” Now, at age 38, Ben takes life one day at a time—without alcohol or other drugs—grateful to a be part of his young family in a way he never could when beer and gin comprised his priority list. “I’m learning to be present for my family,” says Ben. “I finally understand what that means, and it’s something I strive to do every day: Be home for dinner, cook dinner, serve them, pick up the house and set an example for my kids.” His enthusiastic and lasting sobriety landed Ben a job coordinating recovery services for young adults who either attend or want to attend the College of St. -

Growing Knowledge Together: Using Emergent Learning and EL Maps for Better Results Marilyn Darling Charles Parry

VOLUME 8, NUMBER 1 Reflections The SoL Journal on Knowledge, Learning, and Change FEATURE ARTICLES Growing Knowledge Together: Using Emergent Learning and EL Maps for Better Results Marilyn Darling Charles Parry Conflict Alchemy: A Practical Paradigm for Conflict Solutions David Pauker Learning Together for Good Decision Making Arie de Geus E M E R G I N G K N O W L E D G E Developing High Potential Leaders with Strategy Cafés Jim Myracle Diane Oettinger BOOK EXCERPT Leadership Agility: Five Levels of Mastery for Anticipating and Initiating Change Bill Joiner Steve Josephs RECOMMENDED READING ISTOCKPHOTOS Published by The Society for Organizational Learning reflections.solonline.org ISSN 1524-1734 PUBLISHER’S NOTE 8 . 1 COLLECTIVE INTELLIGENCE HAS BECOME A CATCH PHRASE FOR social processes – such as collaboration – and cooperation that allow us to realize possibilities that would otherwise remain latent. In this issue, contributors to Reflections offer cases studies, research, and new methods that help us name what we know from experience, therefore improving our conscious practice in bringing out the best in each other. How do you bring great minds together around complex challenges? SoL members Marilyn Darling and Charles Parry offer a method in our first feature C. Sherry Immediato “Growing Knowledge Together: Using Emergent Learning and EL Maps for Better Results.” The authors have previously developed and reported on AARs (After-Action Reviews), particularly for use in non-military settings. Their experience led them to recog- nize that a method was needed to help groups consciously capture learning that occurred over multiple events. Emergent Learning (EL) maps offer a simple yet powerful approach to recognize patterns and come up with more systemic solutions through capturing data or results, framing hypotheses, and articulating next steps. -

Trends in Political Television Fiction in the UK: Themes, Characters and Narratives, 1965-2009

This item was submitted to Loughborough’s Institutional Repository (https://dspace.lboro.ac.uk/) by the author and is made available under the following Creative Commons Licence conditions. For the full text of this licence, please go to: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ Trends in political television fiction in the UK: Themes, characters and narratives, 1965-2009. 1 Introduction British television has a long tradition of broadcasting ‘political fiction’ if this is understood as telling stories about politicians in the form of drama, thrillers and comedies. Vote, Vote for Nigel Barton (1965) is generally considered the first of these productions for a mass audience presented in the then usual format of the single television play. Ever since there has been a regular stream of such TV series and TV-movies, varying in success and audience appeal, including massive hits and considerable failures. Television fiction has thus become one of the arenas of political imagination, together with literature, art and - to a lesser extent -music. Yet, while literature and the arts have regularly been discussed and analyzed as relevant to politics (e.g. Harvie, 1991; Horton and Baumeister, 1996), political television fiction in the UK has only recently become subject to academic scrutiny, leaving many questions as to its meanings and relevance still to be systematically addressed. In this article we present an historical and generic analysis in order to produce a benchmark for this emerging field, and for comparison with other national traditions in political TV-fiction. We first elaborate the question why the study of the subject is important, what is already known about its themes, characters and narratives, and its capacity to evoke particular kinds of political engagement or disengagement. -

KINDERGARTEN READINESS NIGHT Panelists Sarah Collins

PANEL DISCUSSION- KINDERGARTEN READINESS NIGHT Panelists ● Sarah Collins– Five Mile teacher and parent of TT grad ● Wendy Morgan- Kindergarten Teacher at STEM K-8 West Seattle ● Genya Scharks–K/1 Teacher at Pathfinder ● Erin Hoener– program supervisor at TT Thank you panelists for being here tonight! 1. There are many ways for a child to be “ready” for kindergarten. Among the many skills, which skills do you believe to be the most important? Follow up: How did/do you support your child/children to develop these skills? -S: Academically, my daughter is right in the thick of it but she needs social & emotional support support -G: Independence, get lunchbox and backpack, get shoes on … -E: Getting kids ready to learn so their brains are ready for the rest of the day. Competence and High scope steps of conflict resolution. -W: Take it slow when K begins, take it slow with after school enrichment. Keep life simple the first few months. -R: You can expect a lot of meltdowns in the first month, be soft and gentle with how your child is feeling and experiencing K. 2. A lot of families feel pressure for their child to be ‘academically ready.’ Can you shed light into academic readiness? -W: Being able to write at least some of the letters in their name. Basic cutting skills or having experience with tools like scissors. -G: We’ve noticed in last 3 years especially kids are coming in with more skills. Best thing you can do is just read to your kids. If you know your kid takes a little longer to learn something, you can expose them to it early to make the road a little easier at the beginning. -

Walking the Dead Sabrina Leigh Boyer

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2004 Walking the Dead Sabrina Leigh Boyer Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES WALKING THE DEAD By SABRINA LEIGH BOYER A Thesis submitted to the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2004 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Sabrina Boyer defended April 22, 2004. ___________________________ Virgil Suarez Professor Directing Thesis ____________________________ Maxine Montgomery Committee Member ____________________________ Elizabeth Stuckey-French Committee Member Approved: _______________________________________ Bruce Boehrer, Graduate Studies, Department of English _______________________________________ Donald Foss, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract …………………………………………………………………………………..iv 1. PART ONE ……………………………………………………………………………. 1 2. PART TWO ……………………………………………………………………………25 BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH ……………………………………………………………..52 iii ABSTRACT The topic of my master’s thesis is a long time coming. Since entering the graduate program, even attending Florida State University as an undergraduate and taking my first writing workshop my sophomore year, I have been writing, essentially, about the same topic in different forms. The subject is my father. The first story I wrote was about a girl who wanted the life of her neighbor because her own life was not perfect. It was real. It had flaws. The father in that first piece of fiction was my father. He had a heart attack. He was living past his prospective expiration date. -

Danger, Danger

FINAL-1 Sat, Apr 27, 2019 6:22:37 PM tvupdateYour Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment For the week of May 5 - 11, 2019 Emily Watson stars in “Chernobyl” INSIDE Danger, •Sports highlights Page 2 •TV Word Search Page 2 •Family Favorites Page 4 Hollywood Q&A Page14 danger • On Monday, May 6, join Soviet scientist Valery Legasov (Jared Harris, “The Terror”), nuclear physicist Ulana Khomyuk (Emily Watson, “Genius”) and head of the Bureau for Fuel and Energy of the Soviet Union Boris Shcherbina (Stellan Skarsgård, “River”), as they seek to uncover the truth behind one of the world’s worst man-made catastrophes in the premiere of “Chernobyl,” on HBO. WANTED WANTED MOTORCYCLES, SNOWMOBILES, OR ATVS To advertise here GOLD/DIAMONDS BUY SELL please call ✦ 40 years in business; A+ rating with the BBB. TRADE ✦ For the record, there is only one authentic CASH FOR GOLD, PARTS & ACCESSORIESBay 4 (978) 946-2375 Group Page Shell We Need: SALES & SERVICE Motorsports 5 x 3” Gold • Silver • Coins • Diamonds MASS. MOTORCYCLE1 x 3” We are the ORIGINAL and only AUTHENTIC INSPECTIONS CASH FOR GOLD on the Methuen line, above Enterprise Rent-A-Car 1615 SHAWSHEEN ST., TEWKSBURY, MA at 527 So. Broadway, Rte. 28, Salem, NH • 603-898-2580 978-851-3777 Open 7 Days A Week ~ www.cashforgoldinc.com WWW.BAY4MS.COM FINAL-1 Sat, Apr 27, 2019 6:22:38 PM COMCAST ADELPHIA 2 CHANNEL Kingston Sports Highlights Atkinson Londonderry 10:30 p.m. NESN Red Sox Final Live ESPN Softball NCAA ACC Tournament NESN Baseball MLB Seattle Mariners Salem Sunday Sandown Windham (60) TNT Basketball NBA Playoffs Live Women’s Championship Live at Boston Red Sox Live GUIDE Pelham, 10:55 a.m. -

Arlene Shechet

Arlene Shechet Education M.F.A. Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, RI B.A. New York University, NYC Selected One Person Exhibitions 2021 Together: Pacific Time, Pace Gallery, Palo Alto, CA 2020 Skirts, Pace Gallery, New York, NY 2019 Arlene Shechet: Sculpture, Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects. Jan. 2019. 2018 Full Steam Ahead, Mad Square Park, NYC. Sept 25, 2018 – Apr 28, 2019. More Than I Know, Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, NE. June 2 – Sept 9. Arlene Shechet: Some Truths, Almine Rech Gallery, Paris. Apr 21 – May 26 2017 In the Meantime, Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago. Apr 27 – May 27 2016 From Here on Now, Philips Collection, Washington DC. Oct. 20, 2016 – Jan. 22, 2017 Turn Up the Bass, Sikkema Jenkins & Co. NYC. Oct. 14 – Nov. 16 Still Standing, The Box, Pippy Houldsworth Gallery, London, Sept. 9 - Oct.15 Porcelain, No Simple Matter: Arlene Shechet and the Arnold Collection, The Frick Collection, NYC, May 2016 – May 2017 Urgent Matter, Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis. Jan. 15 - Apr. 11. 2015 All At Once, ICA Boston, June 10 - Sept. 7. (catalogue) Blockbuster, Lora Reynolds Gallery, Austin, TX. Jan. 24 - Mar. 21. 2014 Meissen Recast, RISD Museum, Providence, RI. Jan. 17 - June 8. 2013 Slip, Sikkema Jenkins & Co., NYC, Oct. 10 - Nov. 16. That Time, Weatherspoon Art Museum, Greensboro, NC, traveling from VCUarts. June 15 - Sept. 15. 2012 Breaking the Mold, Nature Morte Berlin. Oct. 19 - Nov. 17. That Time, Anderson Gallery, VCUarts, Richmond, VA. Sept. 7 - Dec. 9. SUM, Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, Overland Park, KS, May 25 - Sept. 2. -

Get Into the Thick of It a Plethora of Places to Go and Things to the Land of I Thought the Crowd Was a Little Thin Do

August 2006 News from siderably since you last saw it) you’ll find Get Into the Thick of It a plethora of places to go and things to the Land of I thought the crowd was a little thin do. But also that Sipapu is right around when I arrived at the coffee shop this the corner, and with it the winding down Sunday morning. But instead it turned of the riding season. Of course, in New Enchantment out I was a little early, if you can believe Mexico the end of the season is also the that. In the half hour after I got there, best riding of the year. We truly live in BMW Riders bikes fairly poured in, filling up the park- the Land of Enchantment. ing lot. After an extended tire kicking We also seem to have a somewhat pre- session I headed north to Madrid, Santa dictable monsoon this year, so that you Fe and the Jemez. The bike count was up, can get some miles in the morning and way up. The roads were thick with them. be back before the afternoon rains arrive. The Mine Shaft hadn’t kicked into gear Of course, all bets are off in the moun- yet, but the Madrid coffee shops all had bikes in front of them, as well as both sides of the short street. I passed others headed for the mountains through Santa Fe, and saw them in pairs and dozens in the Jemez. It didn’t look like a single New Mexico motorcycle was in the garage. -

Mary, Best Evangelist in the World Today Dear Friends, Let Me Begin

Mary, Best Evangelist in the World Today Dear Friends, Let me begin this evening by sharing a marvel with you. God is so gracious. He gives us so many chances to “get it right”. We could have got along with one Gospel in the New Testament, but He gave us four! We could have got along with just Medjugorje, or just Damascus, or just Kibeho, or just San Nicolas, or just Amsterdam, or just Naju, or just Hrushiv, or just Akita, or just Betania, or just Cuapa, not to mention Fatima and Lourdes; but He has given us all of them, and more besides! In particular, He confirmed Amsterdam for us by Akita, half-a-world away in a totally different culture. And He compels us to take Our Lady’s mission in Medjugorje seriously by substantially duplicating it in San Nicolas, Argentina, simultaneously, half-a-world away. This is such a grace because, although there has been controversy around Medjugorje from the beginning due to the local politics – both church and civil – there has been no controversy at all around San Nicolas. The settings are so different, the visionaries are so different (six children in Medjugorje, one grandmother in San Nicolas), the manner of experiencing the apparitions is so different, even the confirming signs are different. But the mission and the contents of the messages are largely the same. The non-controversial one serves to substantiate the controversial one. If you have trouble with Medjugorje, you can ignore it and still end up in the same place spiritually by paying attention to San Nicolas.