Amicus Brief Re South Winds V. Stitt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Legislators for 2019 Session

New Legislators for 2019 Session District Incumbent New Legislator HD 02 John Bennett (R – Sallisaw) Jim Olsen (R – Roland) HD 03 Rick West (R – Heavener) Lundy Kiger (R – Poteau) HD 06 Chuck Hoskin (D – Vinita) Rusty Cornwell (R – Vinita) HD 10 Travis Dunlap (R – Bartlesville) Judd Strom (R – Copan) HD 11 Earl Sears (R – Bartlesville) Derrel Fincher (R – Bartlesville) HD 14 George Faught (R – Muskogee) Chris Sneed (R – Fort Gibson) HD 15 Ed Cannady (D – Porum) Randy Randleman (R – Eufala) HD 17 Brian Renegar (D – McAlester) Jim Grego (R – Wilburton) HD 18 Donnie Condit (D – McAlester) David Smith (R – McAlester) HD 20 Bobby Cleveland (R – Slaughterville) Sherrie Conley (R – Newcastle) HD 24 Steve Kouplen (D – Beggs) Logan Phillips (R – Mounds) HD 25 Todd Thomsen (R – Ada) Ronny Johns (R – Ada) HD 27 Josh Cockroft (R – Tecumseh) Danny Sterling (R – Tecumseh) HD 31 Jason Murphey (R – Guthrie) Garry Mize (R – Edmond) HD 33 Greg Babinec (R – Cushing) John Talley (R – Stillwater) HD 34 Cory Williams (D – Stillwater) Trish Ranson (D – Stillwater) HD 35 Dennis Casey (R – Morrison) Ty Burns (R – Morrison) HD 37 Steve Vaughan (R – Ponca City) Ken Luttrell (R – Ponca City) HD 41 John Enns (R – Enid) Denise Crosswhite-Hader (R – Yukon) HD 42 Tim Downing (R – Purcell) Cynthia Roe (R – Lindsay) HD 43 John Paul Jordan (R – Yukon) Jay Steagall (R – Yukon) HD 45 Claudia Griffith (D – Norman) Merleyn Bell (D – Norman) HD 47 Leslie Osborn (R – Mustang) Brian Hill (R – Mustang) HD 48 Pat Ownbey (R – Ardmore) Tammy Townley (R – Ardmore) HD 61 Casey Murdock -

2020 Sine Die Complete Document

2020 Sine Die Presented by the Oklahoma Municipal League The Oklahoma Municipal League 201 N.E. 23rd Street, Oklahoma City, OK 73105 (405) 528-7515 or (800) 324-6651 www.oml.org June 2020 © 2020 Oklahoma Municipal League, Inc. Published by the Oklahoma Municipal League, Inc. June 2020 Managing Editor: Mike Fina Contributing Writers: Sue Ann Nicely, Jodi Lewis, Missy Kemp © 2020 Oklahoma Municipal League, Inc. SINE DIE TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the Director ........................................................................................................................................................... i The Legislative Department ................................................................................................................................................... iii Sine Die – Report Format ........................................................................................................................................................ v Bill Number Index by Effective Date...................................................................................................................................... vii Bills That May Impact Municipal Departments ....................................................................................................................... 1 2020 Legislative Session Overview .......................................................................................................................................... 6 Effective Date of Bills Summary ............................................................................................................................................. -

Senate Journal

1 Senate Journal First Regular Session of the Fifty-eighth Legislature of the State of Oklahoma First Legislative Day, Tuesday, January 5, 2021 COMMUNICATION November 23, 2020 The Honorable J. Kevin Stitt Governor, State of Oklahoma 2300 N. Lincoln Boulevard Oklahoma City, OK 73105 Dear Governor Stitt, Over the last six years, it has been my sincere honor to serve and represent the constituents of Senate District 22. I have done my best to be a voice for voters in Piedmont, Yukon, NW Oklahoma City and Edmond, and they believed in me enough to elect me twice to this senate seat. I’m pleased to have been a part of so many positive changes during my tenure. In 2016, voters passed State Question 792, supporting alcohol modernization which opened the door for new businesses and opportunities across Oklahoma, resulting in nearly 5,000 new jobs. With the passage of State Question 788 and the successful enactment of HB 1269, of which I was the Senate author, Oklahoma is working to reduce our mass incarceration rates and the related fiscal and social costs that go with it. I’d be remiss if I did not mention supporting the largest increase in public education funding in the history of our state in 2018 totaling almost half a billion dollars, and the subsequent passage of an additional $120M in 2019 which you championed. But more important than these, are the families who have been impacted by legislation I carried. Two bills in particular, one which standardized investigations following the sudden, unexplained death of infants in Oklahoma, and the second which delayed the release of autopsy reports to the media so next of kin would be given time to process the information contained in the reports, are some of my proudest moments of service. -

Winter 2021 Journal

OKWINTER 2021 VOL. 84, L NO. 4 AHOMTHE JOURNAL OF THE OKLAHOMA A OSTEOPATHIC D.O. ASSOCIATION YOU DESERVE THE BEST. INTRODUCING PLICO + MEDPRO GROUP We’re bringing the best of PLICO and MedPro to provide you unparalleled defense, expertise and service, including: • Advanced products and services, from healthcare liability to cyber extortion coverages • National claims and risk management resources paired with trusted, local expertise • A++ financial strength ratings from A.M. Best Protect your business, assets and reputation with Oklahoma’s most dynamic healthcare liability solution. Call or visit us online to learn more. 405.815.4800 | PLICO.COM ENDORSED BY OKLAHOMA HOSPITAL ASSOCIATION | OKLAHOMA STATE MEDICAL ASSOCIATION | OKLAHOMA OSTEOPATHIC ASSOCIATION A.M. Best rating as of 7/21/16. MedPro Group is the marketing name used to refer to the insurance operations of The Medical Protective Company, Princeton Insurance Company, PLICO, Inc. and MedPro RRG Risk Retention Group. All insurance products are administered by MedPro Group and underwritten by these and other Berkshire Hathaway affiliates, including National Fire & Marine Insurance Company. Product availability is based upon business and regulatory approval and differs among companies. Visit www.medpro.com/affiliates for more information. ©2016 MedPro Group Inc. All Rights Reserved. OKLAHOMA OSTEOPATHIC ASSOCIATION OFFICERS Richard W. Schafer, DO, FACOFP, President (Tulsa District) Jason L. Hill, DO, FACOFP, President-Elect (Eastern District) Jonathan K. Bushman, DO, Vice-President (Northwest District) Timothy J. Moser, DO, FACOFP, Past President (South Central District) LeRoy E. Young, DO, FAOCOPM dist., Interim Secretary/Treasurer TRUSTEES Rebecca D. Lewis, DO (Northwest District) Jonathan B. Stone, DO, MPH, FAAPMR (South Central District) Justin S. -

Agenda Meeting of the ODL Board July 16, 2021 | 10:00 A.M

Agenda Meeting of the ODL Board July 16, 2021 | 10:00 a.m. South Conference Room 200 N.E. 18 Street Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73105 The Board may discuss, table, vote to approve or disapprove, change the sequence of any agenda item, or decide not to discuss any item on the agenda. 1. Call to Order, Roll Call, and Compliance with Open Meeting Act 2. Welcome and introduction of ODL Board Members 3. Consider approval of minutes a. April 30, 2021 regular meeting ................................................................................................... 1 b. June 2, 2021 special meeting ...................................................................................................... 4 4. Consider acceptance of financial reports a. Financial Report for SFY2021 ...................................................................................................... 6 b. LSTA Quarterly Grant Accrual Report ....................................................................................... 11 5. Director’s Report a. Agency Activities ....................................................................................................................... 12 b. Legislative Report ...................................................................................................................... 18 c. Staffing update .......................................................................................................................... 22 6. Consider approval of Distribution Plan American Rescue Plan Funds allotted to Oklahoma Department -

OEA 2018 Election Guide

OEA 2018 Election Guide Read the full responses from all participating candidates at okea.org/legislative. 1 2018 Election Guide: Table of Contents State Senate Page 7 State House of Representatives Page 30 Statewide Elections Page 107 Congress Page 117 Judicial Elections Page 123 State Questions Page 127 Candidate Recommendaitons Page 133 Need help? Contact your regional team. The Education Focus (ISSN 1542-1678) Oklahoma City Metro, Northwest, Southeast is published quarterly for $5 and Southwest Teams by the Oklahoma Education Association, The Digital Education Focus 323 E. Madison, Okla. City, OK 73105 323 E. Madison, Oklahoma City, OK 73105. 800/522-8091 or 405/528-7785 Periodicals postage paid at Okla. City, OK, Volume 35, No. 4 and additional mailing offices. The Education Focus is a production Northeast and Tulsa Metro Teams POSTMASTER: Send address changes of the Oklahoma Education Association’s 10820 E. 45th , Suite. 110, Tulsa, OK, 74146 to The Education Focus, PO Box 18485, Communications Center. 800/331-5143 or 918/665-2282 Oklahoma City, OK 73154. Alicia Priest, President Katherine Bishop, Vice President Join the conversation. David DuVall, Executive Director okea.org Amanda Ewing, Associate Executive Director Facebook – Oklahoma.Education.Association Doug Folks, Editor and Student.Oklahoma.Education.Association Bill Guy, Communications twitter.com/okea (@okea) Carrie Coppernoll Jacobs, Social Media instagram.com/insta_okea Jacob Tharp, Center Assistant pinterest.com/oeaedupins Read the full responses from all participating candidates at okea.org/legislative. 2 2018 Election Guide Now is the time to persevere Someone once said that “Perseverance is the hard work you do after you get tired of the hard work you already did.” NOW is the time to roll up our sleeves, dig in, and persevere! When walkout at the apitol was over, I stood in a press conference with my colleagues and announced that what we didn’t gain this legislative session, we would next gain in the next. -

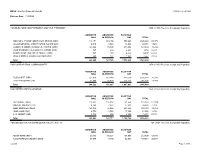

Election Summary Results 11/9/2020 11:42 AM

MESA - Election Summary Results 11/9/2020 11:42 AM Election Date: 11/3/2020 FOR ELECTORS FOR PRESIDENT AND VICE PRESIDENT 1950 of 1950 Precincts Completely Reporting ABSENTEE ABSENTEE ELECTION MAIL IN-PERSON DAY TOTAL DONALD J. TRUMP | MICHAEL R. PENCE (REP) 111,171 109,186 799,923 1,020,280 65.37% JO JORGENSEN | JEREMY SPIKE COHEN (LIB) 4,615 1,548 18,568 24,731 1.58% JOSEPH R. BIDEN | KAMALA D. HARRIS (DEM) 163,046 55,808 285,036 503,890 32.29% JADE SIMMONS | CLAUDELIAH J. ROZE (IND) 797 236 2,621 3,654 0.23% KANYE WEST | MICHELLE TIDBALL (IND) 707 270 4,620 5,597 0.36% BROCK PIERCE | KARLA BALLARD (IND) 549 137 1,861 2,547 0.16% Total 280,885 167,185 1,112,629 1,560,699 FOR CORPORATION COMMISSIONER 1950 of 1950 Precincts Completely Reporting ABSENTEE ABSENTEE ELECTION MAIL IN-PERSON DAY TOTAL TODD HIETT (REP) 152,676 117,089 830,259 1,100,024 76.10% TODD HAGOPIAN (LIB) 91,846 36,818 216,772 345,436 23.90% Total 244,522 153,907 1,047,031 1,445,460 FOR UNITED STATES SENATOR 1950 of 1950 Precincts Completely Reporting ABSENTEE ABSENTEE ELECTION MAIL IN-PERSON DAY TOTAL JIM INHOFE (REP) 111,687 105,897 761,556 979,140 62.91% ROBERT MURPHY (LIB) 4,269 2,353 27,813 34,435 2.21% ABBY BROYLES (DEM) 160,376 55,942 293,445 509,763 32.75% JOAN FARR (IND) 2,772 1,725 17,155 21,652 1.39% A. -

Federal Election Commission First General Counsel's

MUR759401321 1 FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION 2 3 FIRST GENERAL COUNSEL’S REPORT 4 5 MUR: 7594 6 DATE COMPLAINT FILED: April 11, 2019 7 DATE OF NOTIFICATION: April 18 and 22, 2019 8 LAST RESPONSE RECEIVED: October 16, 2019 9 DATE ACTIVATED: September 11, 2019 10 11 EARLIEST EXPIRATION OF SOL: March 6, 2022 12 ELECTION CYCLE: 2018 13 14 COMPLAINANT: Alexander Austin 15 16 RESPONDENTS: Enbridge, Inc. 17 Enbridge (U.S.) Inc. 18 Enbridge (U.S.) Inc. Political Action Committee 19 and K. Ritu Talwar, as Treasurer 20 Enbridge Energy Company, Inc. 21 52 Federal Committee Respondents and Treasurer 22 and 252 State Committee Respondents 23 identified on Appendix A 24 25 RELEVANT STATUTES AND 52 U.S.C. § 30121 26 REGULATIONS: 11 C.F.R. § 110.20 27 28 INTERNAL REPORTS CHECKED: Disclosure Reports 29 30 FEDERAL AGENCIES CHECKED: None 31 32 33 I. INTRODUCTION 34 The Complaint alleges that Enbridge Inc., a Canadian company, violated the Federal 35 Election Campaign Act of 1971, as amended (the “Act”), in connection with contributions to 36 political committees during the 2018 election cycle.1 The contributions at issue in the Complaint 1 Compl. at 1 (Apr. 11, 2019). MUR759401322 MUR 7594 (Enbridge, Inc., et al.) First General Counsel’s Report Page 2 of 12 1 were made by Enbridge (U.S.) Inc. Political Action Committee (“Enbridge PAC”), a separate 2 segregated fund (“SSF”) of Enbridge Inc.’s U.S. subsidiary, Enbridge (U.S.) Inc.2 3 Enbridge Inc., Enbridge (U.S.) Inc., and Enbridge PAC (collectively, “Enbridge 4 Respondents”)3 assert that the Complaint is baseless because the contributions were made by 5 Enbridge PAC, not Enbridge Inc.4 The Enbridge Respondents further assert that the PAC 6 complied with Commission precedent permitting a U.S. -

Download the Fall 2018

The Magazine of the Oklahoma Farm Bureau ® Fall 2018 • Vol. 71 No. 4 Seeding withknowledge Oklahoma Farm Bureau Women’s Leadership Committee Chair Kitty Beavers looks back on eight years of serving, educating and advocating for agriculture. A fine, feathered tradition Producing poultry ethically and responsibly Partners in protection The OKFB Insurance family pulls together Forward foundation A new name and a renewed focus Relax: freedom of choice and peace of mind. No networks, no referrals, and no hidden costs? Yes! Which means you can keep your doctors or choose a new one. With our Medicare Supplements, you have lots of choices. And with eight affordable plans, you owe it to yourself to see how you can save. Just visit mhinsurance.com and compare rates. Or better yet, call us, and let us help you find the plan that best fits your needs. HAVE QUESTIONS? TALK TO A MEDICARE SUPPLEMENT EXPERT. CALL 1-888-708-0123 OR VISIT MHINSURANCE.COM. We make Medicare Supplements easy. Like us: Members Health Insurance MH-OKG-CERTA-FL13-239, MH-OKG-CERTB-FL13-240, Insured by Members Health Insurance Company, Columbia, TN. Not connected with or endorsed by the U.S. or state government. This is a solicitation of insurance and a representative MH-OKG-CERTC-FL13-241, MH-OKG-CERTD-FL13-242, of Members Health Insurance Company may contact you. Benefits are not provided for expenses incurred while coverage under the group policy/certificate is not in force, expenses MH-OKG-CERTF-FL13-243, MH-OKG-CERTG-FL13-244, MH-OKG-CERTM-FL13-245, MH-OKG-CERTN-FL13-246 payable by Medicare, non-Medicare eligible expenses or any Medicare deductible or copayment/coinsurance or other expenses not covered under the group policy/certificate. -

Nextera Energy PAC Contributions to State Candidates January 1 – June 30, 2020

NextEra Energy PAC Contributions to State Candidates January 1 – June 30, 2020 Recipient Amount Chamber State Party Brian Hill for House 2020 $ 5,000 State House OK R Caldwell for State House $ 5,000 State House OK R Chad Caldwell for State House 2020 $ 5,000 State House OK R Friends of Anthony Moore 2020 $ 5,000 State House OK R Friends of Charles McCall 2020 $ 5,000 State House OK R Friends of Chris Kannady 2020 $ 5,000 State House OK R Friends of Chris Kidd 2020 $ 5,000 State Senate OK R Friends of Daniel Pae 2020 $ 5,000 State House OK R Friends of Emily Virgin $ 5,000 State House OK D Friends of Garry Mize 2020 $ 5,000 State House OK R Friends of John Pfieffer $ 5,000 State House OK R Friends of Jon Echols $ 5,000 State House OK R Friends of Kenton Patzkowsky $ 5,000 State House OK R Friends of Kevin Wallace 2020 $ 5,000 State House OK R Friends of Mark Lawson 2020 $ 5,000 State House OK R Friends of Mike Dobrinski 2020 $ 5,000 State House OK R Friends of Nicole Miller 2020 $ 5,000 State House OK R Friends of Tammy West 2020 $ 5,000 State House OK R Friends of Terry O'Donnell 2020 $ 5,000 State House OK R Friends of Todd Hiett 2020 $ 5,000 Corporate Commisioner OK R Greg Treat for Senate 2020 $ 5,000 State Senate OK R Scott Fetgatter for House $ 5,000 State House OK R Trey Caldwell for Rresentative 2020 $ 5,000 State House OK R Friends of Cynthia Roe 2020 $ 3,000 State House OK R Angela Paxton Campaign $ 2,500 State Senate TX R Dunnington for OK House $ 2,500 State House OK D Families for Roland Pederson $ 2,500 State Senate OK R -

P U B L I C P O L I C Y G U I

GREATER OKLAHOMA CITY CHAMBER PUBLIC POLICY GUIDE 2019 WE’LL HELP YOUR BUSINESS THRIVE As a business owner, how do you know when you have the right banking relationship? Does your bank understand your business and help nd ways to grow your prots? At Arvest, you’ll understand that you are top priority right from the beginning, when our bankers get to know you personally and understand the details of your business. We’ll help nance your success and build the right solution to meet your very specic needs. Ready to help your business thrive? We are! (405) 677-8711 arvest.com Member FDIC TABLE OF CONTENTS Message from the Chair .....................page 4 Government Relations Staff ...............page 5 2019 Public Policy Priorities ...............page 6 Pro-Business Scorecard ................... page 16 Greater OKC Chamber PAC ............. page 18 Elected Officials Directory ............... page 19 Chamber Leadership ........................ page 42 GOVERNMENT RELATIONS BENEFACTORS 2019 Public Policy Guide 2019 Public Policy GOVERNMENT RELATIONS SPONSORS Enable Midstream Partners Google, Inc. 3 Message from the Chair The Greater Oklahoma City Chamber takes pride in its role as the voice of business for the region, and one of the most important ways we fill that role is by participating in the political process. As we begin the legislative session, the Chamber’s voice is crucial to the region’s continued success. The decisions made at the State Capitol this year on important topics like education funding, health care and transportation will set the course for our city and state for years to come. The document you have in your hands is a playbook for the important topics our elected officials will debate this year, issues that will impact Oklahoma City’s economy and the success of its companies. -

Trust Women Foundation 2019 Oklahoma State Officials And

2019 Oklahoma State Officials and House of Representatives Voting Candidate Office / District Record OFL Party UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE - Kevin Hern DISTRICT 01 Republican UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE - Markwayne Mullin* DISTRICT 02 VRA Republican UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE - Frank D. Lucas* DISTRICT 03 VRA Republican UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE - Tom Cole* DISTRICT 04 VRA Republican UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE - Kendra Horn DISTRICT 05 Democrat Kevin Stitt GOVERNOR 12/12 Republican Matt Pinnell LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR 12/12 Republican Johnny Tadlock* STATE REPRESENTATIVE - DISTRICT 1 VRA Democrat Jim Olsen STATE REPRESENTATIVE - DISTRICT 2 Republican Lundy Kiger STATE REPRESENTATIVE - DISTRICT 3 Republican Matt Meredith* STATE REPRESENTATIVE - DISTRICT 4 VRU Democrat Josh West* STATE REPRESENTATIVE - DISTRICT 5 VRA Republican John L. Myers STATE REPRESENTATIVE - DISTRICT 6 Democrat Ben Loring* STATE REPRESENTATIVE - DISTRICT 7 VRA Democrat Tom Gann* STATE REPRESENTATIVE - DISTRICT 8 VRA Republican Mark Lepak* STATE REPRESENTATIVE - DISTRICT 9 VRA Republican Judd Strom STATE REPRESENTATIVE - DISTRICT 10 Republican Derrel Fincher STATE REPRESENTATIVE - DISTRICT 11 Republican Kevin McDugle* STATE REPRESENTATIVE - DISTRICT 12 VRA Republican Avery Carl Frix* STATE REPRESENTATIVE - DISTRICT 13 VRA Republican Chris Sneed STATE REPRESENTATIVE - DISTRICT 14 Republican Randy Randleman STATE REPRESENTATIVE - DISTRICT 15 Republican Scott Fetgatter* STATE REPRESENTATIVE - DISTRICT 16 VRA Republican Jim Grego STATE REPRESENTATIVE - DISTRICT 17